LGBT-free zone

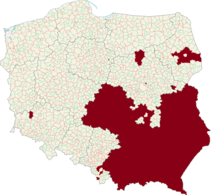

LGBT-free zones (Polish: Strefy wolne od LGBT)[2][3][4][5][6][7] or LGBT ideology–free zones (Polish: Strefy wolne od ideologii LGBT)[8] are municipalities and regions of Poland that have declared themselves unwelcoming of an alleged "LGBT ideology",[9] in order to ban equality marches and other LGBT events.[2][10][11] As of June 2020, some 100 municipalities (including five voivodships), encompassing about a third of the country, have adopted resolutions which have led to them being called "LGBT-free zones".[12][13]

Most of the adopted resolutions are lobbied for by an ultra-conservative[14][15] Catholic organisation, Ordo Iuris.[16][17] While unenforceable and primarily symbolic, the declarations represent an attempt to stigmatize LGBT people.[18][19] The Economist considers the zones "a legally meaningless gimmick with the practical effect of declaring open season on gay people".[20] In a December 2020 report, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights stated that "Far from being merely words on paper, these declarations and charters directly impact the lives of LGBTI people in Poland."[21]

On 18 December 2019, the European Parliament voted, 463 to 107, to condemn the more than 80 such zones in Poland.[2][10][11] In July 2020, the Provincial Administrative Courts (Polish: Wojewódzki Sąd Administracyjny) in Gliwice and Radom ruled that the "LGBT ideology free zones" established by the local authorities in Istebna and Klwów gminas respectively are null and void, stressing that they violate the constitution and are discriminatory against members of the LGBT community living in those counties.[22][23]

Since July 2020, the European Union has denied funding from the Structural Funds and Cohesion Fund to municipalities that have adopted "LGBT-free" declarations, which are in violation of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.[24] Poland is the only member state to have an opt-out from the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which it had signed upon its accession to the EU in 2004. In addition, several European sister cities have frozen their partnerships with the Polish municipalities in question.[25] Due to its violation of European law, including Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union, these zones are considered part of the Polish rule-of-law crisis.[26]

Background[]

In February 2019, Warsaw's liberal mayor Rafał Trzaskowski signed a declaration supporting LGBTQ rights,[19][27] and announced his intention to follow World Health Organization guidelines and integrate LGBT issues into the Warsaw school system sex education curricula.[19] Law and Justice (PiS) politicians objected to the program saying it would sexualize children.[28] PiS party leader Jarosław Kaczyński responded to the declaration, calling LGBT rights "an import" that threatens Poland.[29]

According to The Daily Telegraph, the declaration "enraged and galvanized" conservative politicians and conservative media in Poland, the "LGBT-free zone" declarations emerging as a reaction to the Warsaw declaration. The British newspaper further argues that the conservative establishment is fearful of a liberal transition that may erode the Catholic Church's power in Poland like the transition around the Irish Church. Decreasing Church attendance, rising secularization, and sexual abuse scandals have put pressure on the conservative position.[19]

In May 2019, Polish police arrested civil-rights activist Elżbieta Podleśna for putting up posters of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa with the halo painted rainbow colours for the charge of offending religious sentiment, which is illegal in Poland.[30][31]

Two weeks prior to the 2019 European Parliament election, a documentary on child sex abuse in the Church, was released online.[30] It was expected to hurt the Church-aligned PiS electorally, and was responded to by PiS leader Kaczyński speaking heatedly of the Polish nation and children as "being under attack by deviant foreign ideas", which led conservative voters to rally around PiS.[30] According to feminist scholar Agnieszka Graff, "The attack on LGBT was triggered by the [Warsaw] Declaration, but that was just a welcome excuse", as PiS sought to woo the rural-traditional demographic and needed a scapegoat to replace migrants.[30]

In August 2019, the Archbishop of Kraków, Marek Jędraszewski, said "LGBT ideology" was like a "rainbow plague" in a sermon commemorating the Warsaw uprising.[32][33][34] Not long after, a drag queen simulated Jędraszewski's murder on stage, stirring controversy.[35]

As of 2019, being openly gay in Poland's small towns and rural areas "[takes] increasing physical and mental fortitude" due to the efforts of Polish authorities and the Catholic Church, according to The Daily Telegraph.[19] Public perceptions, however, have been becoming more tolerant of gay people.[19][28] In 2001, the 41 percent of Poles surveyed stating that "being gay wasn't normal and shouldn't be tolerated" dropped to 24 percent in 2017, and the 5 percent who said "being gay was normal" in 2001 had grown to 16 percent in 2017.[28]

Declarations[]

LGBT-free zone motions refer to resolutions passed by some of Polish gminas (municipalities),[36][18] powiats (counties),[37] and voivodeships (provinces)[19] who declared themselves free from “LGBT ideology” in reaction to the Warsaw Declaration.[38][39] While unenforceable, activists say the declared zones represent attempts to exclude the LGBT community[18][19] and called the declarations "a statement saying that a specific kind of people is not welcome there."[18]

The two documents declared by municipalities were a "Local Government Charter of The Rights of The Family",[40] and a "Resolution against LGBT ideology". Both of these documents were labelled in media as "declarations of LGBT-free zones",[41] but neither of them actually contain a statement of exclusion of LGBT people from any territory, activities or rights. The "Charter of Family Rights" focuses on family values in social policies and only refers to LGBT rights indirectly, such as by defining marriage as a relationship "between a man and a woman". The "Resolution against LGBT ideology" does not speak to LGBT people, but declares opposition to an "ideology of the LGBT movement" and introducing sex education in line with WHO education standards and condemns political correctness.[42] An interactive map of Poland marking all municipalities which accepted either one or both of these resolutions, with links to their original texts, is available online, under the titles "Atlas of Hate".[43]

As of August 2019, around 30 different local governments have accepted such resolutions, including four voivodeships in the south-east of the country:[36][44][45][37] Lesser Poland, Podkarpackie, Świętokrzyskie, and Lublin.[44] The four Voivodeships form the "historically conservative" part of Poland.[18]

As of February 2020, local governments controlling a third of Poland officially declared themselves as "against "LGBT ideology" or passed “pro-family” Charters, pledging to refrain from encouraging tolerance or funding NGOs working for LGBT rights.[46][47]

Voivodeships[]

- Lublin Voivodeship[48]

- Lesser Poland Voivodeship[9]

- Podkarpackie Voivodeship[49]

- Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship[50]

- Łódź Voivodeship[51]

Powiats[]

- Powiat białostocki[52]

- Powiat bielski[53]

- Powiat dębicki[54]

- Powiat jarosławski[55]

- Powiat kielecki[56]

- Powiat kolbuszowski[57]

- Powiat krasnostawski[58]

- Powiat kraśnicki[59]

- Powiat leski[60]

- Powiat limanowski[61]

- Powiat lubaczowski[62]

- Powiat lubelski[63]

- Powiat łańcucki[64]

- Powiat łowicki[65]

- Powiat łukowski[66]

- Powiat mielecki[67]

- Powiat nowotarski[68]

- Powiat opoczyński[69]

- Powiat przasnyski[70]

- Powiat przysuski[71]

- Powiat puławski[72]

- Powiat radomski[73]

- Powiat radzyński[74]

- Powiat rawski[75]

- Powiat rycki[76]

- Powiat sztumski[77]

- Powiat świdnicki[78]

- Powiat tarnowski[79]

- Powiat tatrzański[80]

- Powiat tomaszowski[81]

- Powiat wieluński[82]

- Powiat włoszczowski[83]

- Powiat zamojski[84]

Gminas[]

- Gromnik (gmina)[85]

- Istebna (gmina),[86] revoked by a court ruling

- Jordanów (gmina wiejska)[87]

- Klwów (gmina),[88] revoked by a court ruling.

- Kraśnik,[89] withdrawn by city council in April 2021[90]

- Lipinki (gmina)[91]

- Łososina Dolna (gmina)[92]

- Niebylec (gmina)[93]

- Serniki (gmina),[94] revoked by a court ruling.[95][96]

- Szerzyny (gmina)[97]

- Trzebieszów (gmina)[98]

- Tuchów[99]

- Tuszów Narodowy (gmina)[100]

- Urzędów (gmina)[101]

- Zakrzówek (gmina)[102]

- Skierniewice[103]

- Radziechowy-Wieprz, repealed in October 2020 by the voivode of the Silesian Voivodeship, [104]

Law and Justice party[]

In the run-up to the 2019 Polish parliamentary election the party has focused on countering "LGBT ideology".[36] In 2019, it rebuked the Warsaw mayor's pro-LGBTQ declaration as "an attack on the family and children" and stated that LGBTQ was an "imported" ideology.[19]

After Archbishop Marek Jędraszewski made his speech calling "LGBT ideology" a "rainbow plague", the Minister of National Defence Mariusz Błaszczak applauded the statement.[33]

Stickers[]

The conservative Gazeta Polska newspaper issued "LGBT-free zone" stickers to readers.[105] The Polish opposition and diplomats, including US ambassador to Poland Georgette Mosbacher, condemned the stickers.[38][106] Gazeta editor in chief Tomasz Sakiewicz replied to the criticism with: "what is happening is the best evidence that LGBT is a totalitarian ideology".[106]

The Warsaw district court ordered that distribution of the stickers should halt pending the resolution of a court case.[107] However Gazeta's editor dismissed the ruling saying it was "fake news" and censorship, and that the paper would continue distributing the stickers.[108] Gazeta continued distribution of the stickers, but modified the decal to read "LGBT Ideology-Free Zone".[107]

In July Polish media chain Empik, the country's largest, refused to stock Gazeta Polska after it issued the stickers.[34] In August 2019, a show organized by the Gazeta Polska Community of America scheduled for October 24 in Carnegie Hall in New York was cancelled after complaints of anti-LGBT ties led to artists pulling out of the show.[109][110]

Demonstrations[]

In Rzeszów, after LGBT activists submitted a request to hold an equality march for gay rights in June 2019, PiS councillors drafted a resolution to make Rzeszów an "LGBT-free zone" as well as outlaw the event itself.[30] Some 29 requests for counter-demonstrations reached city hall, which led mayor Tadeusz Ferenc, of the opposition Democratic Left Alliance, to ban the march due to security concerns.[30] When the ban was then overturned by a court ruling,[30] PiS councillors put forward a resolution outlawing "LGBT ideology", which was defeated by two votes.[30]

Following the violent events in the first Białystok equality march[18][111] and the Gazeta Polska stickers a demonstration for tolerance was held in Gdańsk[112] on 23 July 2019, with the slogan "zone free of zones" (Polish: Strefa wolna od stref).[113][114][115] In Szczecin a demonstration under the slogan of "hate-free zone" (Polish: Strefa wolna od nienawiści) took place,[115][116] and in Łódź left-wing politicians handed out "hate-free zone" stickers.[115][117]

Effects on LGBT residents[]

According to a December 2020 report by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights:

Far from being merely words on paper, these declarations and charters directly impact the lives of LGBTI people in Poland. The Commissioner has heard testimonies about the chilling effect of these documents on residents and institutions, who are increasingly reluctant to be associated with any activity related to the human rights of LGBTI people for fear of reprisals or loss of funds. The Commissioner was told that some media outlets which have reported on these documents have been targeted by legal action, leading some of them to exercise self-censorship. She has also been told about cases of LGBTI residents being refused services by local businesses (e.g. a pharmacy) or organisations being denied the opportunity to hold LGBTI awareness-raising events. Activists working to denounce such declarations have also been subjected to specious lawsuits filed by local governments or conservative organisations and a smear campaign labelling them as liars for using creative advocacy tools, the clear intention being to intimidate and silence them. The Commissioner has received reports of many LGBTI people being shunned by fellow residents.[21]

Reactions[]

Support for declarations[]

Bożena Bieryło, a PiS councilwoman in Białystok County, said the legislation in Białystok county was required due to LGBT "provocations" and "demands" for sex education instruction.[38]

The national PiS party has encouraged the local declarations, with a PiS official handing out medals in Lublin to local politicians who supported the declarations.[36]

Criticism of declarations[]

In July 2019, Polish Ombudsman Adam Bodnar stated that "the government is increasing homophobic sentiments" with remarks "on the margins of hate speech".[36] Bodnar said he is preparing an appeal to the administrative court against the declarations, as according to Bodnar they are not only political but also have a normative character that affects the lives of people in the declared region.[37][118]

In July 2019, Warsaw city Councillor Marek Szolc and the (PTPA) released a legal opinion stating that LGBT-free zone declarations stigmatize and exclude people, reminding everyone of article 32 of the Constitution of Poland which guarantees equality and lack of discrimination.[39][119][120]

In August 2019, multiple LGBT community members stated that they feel unsafe in Poland.[33] The left-wing Razem party stated: "Remember how the right [were scared] of the so-called [Muslim] no-go zones? Thanks to the same right, we have our own no-go zones."[121][122]

Liberal politicians and media and human rights activists have compared the declarations to Nazi-era declarations of areas being judenfrei (free of Jews). Left-leaning Italian newspaper la Repubblica called it "a concept that evokes the term 'Judenfrei'".[125][126] Campaign Against Homophobia director Slava Melnyk compared the declarations to "1933, when there were also free zones from a specific group of people."[127] Warsaw's deputy president Paweł Rabiej tweeted, "The German fascists created zones free of Jews. Apartheid, of blacks."[105][124]

In March 2020, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a documentary on the opposition of the LGBT community in Poland against the introduction of LGBT-free zones in the country.[128]

In April 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many within the LGBT community, began handing out rainbow facemasks and other P.P.E. - as a direct protest of the "LGBT-free zoning", within certain local government areas of Poland.[129]

On 17 August 2020, an open letter to the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was published urging the European Union "to take immediate steps in defense of basic European values [...] which have been violated in Poland" and expressing "a deep concern over the future of democracy in Poland". It also appealed to the Polish government to stop targeting sexual minorities as enemies and to withdraw support from organizations promoting homophobia. The signatories of the letter included among others: Pedro Almodóvar, Timothy Garton Ash, Margaret Atwood, John Banville, Judith Butler, John Maxwell Coetzee, Stephen Daldry, Luca Guadagnino, Ed Harris, Agnieszka Holland, Isabelle Huppert, Jan Komasa, Yorgos Lanthimos, Mike Leigh, Paweł Pawlikowski, Volker Schlöndorff, Stellan Skarsgård, Timothy Snyder, Olga Tokarczuk, Adam Zagajewski and Slavoj Žižek.[130][131][132]

In September 2020, the American presidential candidate Joe Biden also condemned LGBT-free zones in Poland via Twitter stating that "LGBTQ+ rights are human rights — and “LGBT-free zones” have no place in the European Union or anywhere in the world".[133]

The organization, which keeps track of the anti-LGBT resolutions, was nominated for the Sakharov Prize by 43 MEPs.[134]

As of 2020, the watchdog group ILGA-Europe identified Poland's respect for LGBTI rights as the worst of all 27 EU countries.[135][136]

Reaction from the European Union[]

On 18 December 2019, the European Parliament voted (463 to 107) in favour of condemning the more than 80 LGBT-free zones in Poland. Parliament demanded that "Polish authorities (are) to condemn these acts and (are) to revoke all resolutions attacking LGBT rights". According to the EU Parliament the zones are part of "a broader context of attacks against the LGBT community in Poland, which include growing hate speech by public and elected officials and public media, as well as attacks and bans on Pride marches and actions such as 'Rainbow Fridays'.".[2][10][11]

Based upon numerous complaints that "some local governments have adopted discriminatory declarations and resolutions targeting LGBT people", the European Commission wrote to the governors of five Voivodeships – Lublin, Łódź, Lesser Poland, Podkarpackie, and Świętokrzyskie – on 2 June 2020, instructing them to investigate local resolutions proclaiming LGBT-free zones or a "Charter of Family Rights", and whether such resolutions constituted discriminatory actions towards LGBT-identifying people or not.[137] The letter can be seen as an extension of the 2019 vote in the European Parliament condemning the zones, as it notes that failure by Poland to adhere to common values of the European Union of “respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities”, as stated in Article 2 of the 2012 European Union Treaty[138] could result in the loss of EU funds granted to the Republic of Poland in the future, such as European Structural and Investment.[137]

In July 2020, Commissioner Dalli announced that applications for EU-funded town twinnings from six Polish towns had been rejected because of their adoption of "LGBT-free" or "family rights" resolutions.[139]

In her September 2020 State of the European Union speech, Ursula von der Leyen stated, "LGBTQI-free zones are humanity free zones. And they have no place in our Union."[140][141]

In March 2021, the European Parliament declared the entire European Union an "LGBTIQ Freedom Zone" in response to the backsliding of LGBTIQ rights in some EU countries, notably in Poland and in Hungary.[142]

International agreements[]

In February 2020, the French commune of Saint-Jean-de-Braye decided to suspend the partnership with the Polish city of Tuchów as a result of the controversial anti-LGBT resolution passed by the Tuchów authorities.[143][144][145] In February 2020, the French commune of Nogent-sur-Oise suspended its partnership with the Polish city of Kraśnik as a reaction to the passing of an anti-LGBT resolution by the city authorities.[146] In February 2020, the French region of Centre-Val de Loire suspended its partnership with the Lesser Poland Voivodeship as a response to the establishment of an "LGBT-free zone" resolution by the voivodeship's authorities.[147][148][149] In May 2020, the German city of Schwerte ended its city partnership with the Polish city of Nowy Sącz after 30 years of cooperation due to the town's adoption of a resolution discriminating against LGBT people.[150] In July 2020, the Dutch city of Nieuwegein as well as the French city of Douai ended their twin city agreements with the Polish city of Puławy due to a "gay free zone" proclamation made in the latter.[151][152] On 12 October 2020, the Irish city of Fermoy ended its twin town agreement with Nowa Dęba after 14 years of cooperation as a reaction to the homophobic LGBT-free zone declaration adopted by the Polish city's authorities.[153] On 13 November 2020, the Belgian municipality of Puurs-Sint-Amands suspended its 20-year-long partnership with the Polish town of Dębica because of the town's adoption of the Charter of The Rights of The Family, which discriminates LGBT people.[154]

In July 2020, the European Commissioner for Justice and Equality Helena Dalli announced that six Polish cities which adopted the "LGBT-free zones" would not be granted EU funds related to financing projects within the EU twinning project framework as a direct consequence of their discriminatory policies directed against members of the LGBT community.[155] The decision met with criticism from the Minister of Justice Zbigniew Ziobro, however, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen defended the decision adding that "Our treaties ensure that every person in Europe is free to be who they are, live where they like, love who they want, and aim as high as they want."[156] However, on 18 August, Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced that the town of Tuchów in southern Poland would now receive 250,000 zlotys ($67,800) from the ministry's Justice Fund, to compensate for the EU funding reversal.[157]

In September 2020, Ine Marie Eriksen Søreide, the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, announced that the Polish municipalities which introduced the LGBT-free zones would be denied the EEA and Norway Grants whose aim is the reduction of social and economic disparities in the European Economic Area (EEA). Poland is the biggest beneficiary of these funds and could potentially lose millions of euros of financial aid.[158] The suspension of funds only applies to the government bodies that have themselves adopted resolutions and does not apply to non-governmental organizations that operate in the LGBT-free zones.[159]

In September 2020, a group of MEPs published a letter addressed to the European Olympic Committees (EOC) in which they demanded to respect the rights of LGBTI athletes and expressed an idea to host the 2023 European Games, which had been scheduled to take place in Kraków, in a different location due to the region's LGBT-free zone status.[160][161]

See also[]

- Anti-gender movement

- Backlash (sociology)

- Censorship of LGBT issues

- LGBT agenda

- LGBT history in Poland

- LGBT rights in Poland

- Moral panic

- Opposition to LGBT rights

- August 2020 LGBT protests in Poland

- Political activity of the Catholic Church on LGBT issues in Poland

References[]

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (25 February 2020). "A Third of Poland Declared 'LGBT-Free Zone'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "European Parliament slams 'LGBTI-free' zones in Poland". Deutsche Welle. 18 December 2019.

- ^ Hajdari, Una (31 December 2019). "The Demagogue's Cocktail of Victimhood and Strength". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Activist aims to shame Polish towns opposed to LGBT community". Reuters. 7 February 2020.

- ^ Maurice, Emma Powys (25 February 2020). "A third of Poland has now been declared an 'LGBT-free zone', making intolerance official". PinkNews.

- ^ "As It Happens: Activist fights homophobia in Poland with photo series of 'LGBT-free' zones". CBC Radio. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Assunção, Muri (25 July 2019). "Outrage over 'LGBTQ-free zone' stickers distributed by Polish magazine". New York Daily News.

- ^ Dyjas-Szatkowska, Natalia (5 February 2019). "W Polsce powstają "strefy wolne od ideologii LGBT". Czym mogą skutkować takie działania rozmawiamy z Instytutem Równości". Gazeta Lubuska (in Polish).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Deklaracja Nr 1/19 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z dnia 29 kwietnia 2019 r. w sprawie sprzeciwu wobec wprowadzenia ideologii "LGBT" do wspólnot samorządowych" [Declaration No. 1/19 of the Lesser Poland Regional Assembly of 29 April 2019 on opposition to the introduction of the "LGBT" ideology in local government communities]. Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Lubelskiego w Lublinie [Marshal's Office of the Lublin Voivodeship in Lublin] (in Polish). Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hume, Tim (19 December 2019). "More Than 80 Polish Towns Have Declared Themselves 'LGBTQ-Free Zones'". Vice News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Delaleu, Nicolas (18 December 2019). "Parliament strongly condemns "LGBTI-free zones" in Poland". European Parliament.

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (25 February 2020). "A Third of Poland Declared 'LGBT-Free Zone'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Pronczuk, Monika (30 July 2020). "Polish Towns That Declared Themselves 'L.G.B.T. Free' Are Denied E.U. Funds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Kurasinska, Lidia (14 April 2020). "This Is War': The Story Behind Poland's Bid to Ban Abortion Today". Transitions Online. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Protests at Polish plan to exit convention against domestic violence". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Samorządowa Karta Praw Rodzin". Ordo Iuris (in Polish). 2020.

- ^ "Uchwały anty-LGBT i inne dyskryminujące akty prawne" [Anti-LGBT resolutions and other discriminatory legal acts]. Google Docs (in Polish). 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Why 'LGBT-free zones' are on the rise in Poland". CBC. 27 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Foster, Peter (9 August 2019). "Polish ruling party whips up LGBTQ hatred ahead of elections amid 'gay-free' zones and Pride march attacks". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Charlemagne (21 November 2020). "Life beyond Europe's rainbow curtain". The Economist. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Memorandum on the stigmatisation of LGBTI people in Poland 3 December 2020

- ^ "Sąd w Gliwicach unieważnił uchwałę o "strefie wolnej od LGBT" w gminie Istebna". Salon24 (in Polish). 14 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "WSA unieważnił uchwałę "anty-LGBT" Rady Gminy w Klwowie. Sąd: "W polskiej tradycji jest również tradycja tolerancji"". Wpolityce.pl (in Polish). 15 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Frater, James; Kolirin, Lianne (31 July 2020). "EU blocks funding for six towns that declared themselves 'LGBT-Free Zones'". CNN. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Wanat, Zosia (3 August 2020). "Polish towns pay a steep price for anti-LGBTQ views". Politico.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "European Parliament slams 'LGBTI-free' zones in Poland | DW | 18.12.2019". DW.COM. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Pride and prejudice: Poland at war over gay rights before vote". South China Morning Post. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Goclowski, Marcin; Wlodarczak-Semczuk, Anna (21 May 2019). "Polish towns go 'LGBT free' ahead of bitter European election campaign". Reuters.

- ^ Roache, Madeline (3 July 2019). "Poland Is Holding Massive Pride Parades. But How Far Have LGBTQ Rights Really Come?". TIME. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Ciobanu, Claudia (26 June 2019). "'Foreign Ideology': Poland's Populists Target LGBT Rights". Balkan Insight.

- ^ "LGBT Virgin Mary triggers Polish activist's detention". BBC News. 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Poland's ruling party fuels anti-LGBT sentiment ahead of elections". Financial Times. 11 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Activists warn Poland's LGBT community is 'under attack'". Euronews. 8 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luxmoore, Jonathan (19 August 2019). "Church in Poland continues confrontation with the LGBTQ community". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Bounaoui, Sara (14 August 2019). "Drag queen "symulował zabójstwo" Jędraszewskiego. KEP i RPO komentują kontrowersyjny występ" [Drag queen "simulated the murder" of Jędraszewski: KEP and RPO comment on the controversial performance]. RMF24.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Noack, Rick (21 July 2019). "Polish towns advocate 'LGBT-free' zones while the ruling party cheers them on". The Washington Post. (Reprint at The Independent)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Adam Bodnar: przygotowuję się do zaskarżenia uchwał w sprawie ideologii LGBT" [Adam Bodnar: I'm preparing to appeal against resolutions banning LGBT ideology]. TVN24 (in Polish). 22 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Santora, Marc; Berendt, Joanna (27 July 2019). "Anti-Gay Brutality in a Polish Town Blamed on Poisonous Propaganda". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Konferencja prasowa na rzecz osób LGBT+" [Press release about LGBT+ people]. Polish Society for Anti-Discrimination Law (in Polish). 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Local Government Charter of The Rights of The Family" (PDF). Instytut Ordo Iuris.

- ^ Korolczuk, Elżbieta (8 April 2020). "Poland's LGBT-free zones and global anti-gender campaigns". Centre for East European and International Studies. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko w sp. wprowadzenia ideologii LGBT do wspolnot samorzadowych" [A statement concerning introduction of LGBT ideology into the local community] (PDF). Sejmik of the Lublin Voivodeship (in Polish). 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Atlas nienawiści" [Atlas of Hate]. atlasnienawisci (in Polish). Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pitoń, Angelika (19 July 2019). "Krakowski magistrat odpowiada na homofobiczny akt "Gazety Polskiej"" [The Krakow municipality responds to the homophobic act of "Gazeta Polska"]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Krakow.

- ^ Figlerowicz, Marta (7 August 2019). "The New Threat to Poland's Sexual Minorities". Foreign Affairs. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Powys Maurice, Emma (25 February 2020). "A third of Poland has now been declared an 'LGBT-free zone', making intolerance official". PinkNews. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "A Third of Poland Declared 'LGBT-Free Zone'". Balkan Insight. 25 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Stanowisko Sejmiku Województwa Lubelskiego w sprawie wprowadzenia ideologii "LGBT" do wspólnot samorządowych". Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Lubelskiego w Lublinie (in Polish). 25 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Nr VIII/140/19 Sejmiku Województwa Podkarpackiego z dnia 27 maja 2019 r.w sprawie przyjęcia stanowiska Sejmiku Województwa Podkarpackiego wyrażającego sprzeciw wobec promocji i afirmacji ideologii tak zwanych ruchów LGBT (z ang. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender)" (PDF). Sejmiku Województwa Podkarpackiego (in Polish). 27 May 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Sejmiku Województwa Świętokrzyskiego dotyczące sprzeciwu wobec prób wprowadzenia ideologii "LGBT" do wspólnot samorządowych oraz promocji tej ideologii w życiu publicznym". Sejmiku Województwa Świętokrzyskiego (in Polish). 19 June 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Sejmik przyjął Samorządową Kartę Praw Rodzin". Łódź Voivodeship (in Polish). 28 January 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr IX/84/2019 Rady Powiatu Białostockiego z dnia 25 kwietnia 2019 r. w sprawie Karty LGBT i wychowania seksualnego w duchu ideologii gender". Rady Powiatu Białostockiego (in Polish). 25 April 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr VI/10/86/19 Rady Powiatu w Bielsku-Białej z dnia 30 września 2019 r. w sprawie wsparcia dla konstytucyjnego modelu rodziny opartego na tradycyjnych wartościach". Rady Powiatu w Bielsku-Białej (in Polish). 30 September 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Nr XI.101.2019 z 17 września 2019". Starostwo Powiatowe W Dębicy (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Deklaracja Rady Powiatu Jarosławskiego z dnia 27 czerwca 2019 roku przyjęta podczas obrad VIII sesji w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Powiatu Jarosławskiego (in Polish). 27 June 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Powiatu w Kielcach z dnia 23 sierpnia 2019 r. w sprawie wyrażenia sprzeciwu wobec prób wprowadzania ideologii "LGBT" do lokalnej wspólnoty samorządowej" (PDF). Rady Powiatu w Kielcach (in Polish). 23 August 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Deklaracja Rady Powiatu w Kolbuszowej z dnia 22 sierpnia 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową" (PDF). Rady Powiatu w Kolbuszowej (in Polish). 22 August 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Powiatu w Krasnymstawie z dnia 15 kwietnia 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Powiatu w Krasnymstawie (in Polish). 15 April 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Powiat Kraśnicki wolnym od ideologii „LGBT”. "Imienny wykaz głosowania radnych na VIII sesji Rady Powiatu w Kraśniku VI kadencji w dniu 29 maja 2019 roku" (PDF). Rady Powiatu w Kraśniku (in Polish). 29 May 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Stanowisko nr 1.2019 Rady Powiatu Leskiego w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii „LGBT” przez wspólnotę samorządową. "Protokół VI Sesji Rady Powiatu w Lesku (zwyczajnej) odbytej w dniu 26 kwietnia 2019 r. w Lesku (Kadencja: 2018 r. – 2023 r.)" (PDF). Rady Powiatu Leskiego (in Polish). 26 April 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Samorządowa Karta Praw Rodziny odpowiedzią na "deklaracje o charakterze politycznym"". Limanowa.in (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Deklaracja Rady Powiatu Lubaczowskiego z dnia 6 czerwca 2019 r. przyjęta podczas obrad X sesji przeciw wdrażaniu ideologii LGBT w życiu społecznym" (PDF). Rady Powiatu Lubaczowskiego (in Polish). 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Powiatu w Lublinie z dnia 31 maja 2019 r. Powiat Lubelski wolny od ideologii "LGBT"". Rady Powiatu w Lublinie (in Polish). 31 May 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Aktualności: Samorządowa Karta Praw Rodzin". Powiat Łańcucki (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Redakcja (26 April 2019). "Rada Powiatu Łowickiego przyjęła kontrowersyjny dokument [PEŁNA TREŚĆ]". Łowicz Nasze Miasto (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Nr X/100/2019 Rady Powiatu Łukowskiego z dnia 15 października 2019 r. w sprawie przyjęcia stanowiska wyrażającego protest przeciw działaniom ukierunkowanym na promowanie ideologii ruchów LGBT" (PDF). Rady Powiatu Łukowskiego (in Polish). 15 October 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Powiatu Mieleckiego w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Powiatu Mieleckiego (in Polish). 26 June 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Powiat nowotarski przyjął samorządową kartę praw rodzin". NowyTarg24.tv (in Polish). 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Powiat wprowadza Samorządową Kartę Praw Rodzin". Powiat Opoczno (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Powiat przasnyski przyjął Samorządową Kartę Praw Rodzin". Powiat Przasnyski (in Polish). 11 June 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Powiat przysuski chroni rodzinę". Radio Plus Radom (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Powiatu Puławskiego w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii lansowanej przez subkulturę "LGBT" w Powiecie Puławskim". Rady Powiatu Puławskiego (in Polish). 29 May 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Powiat radomski na straży praw rodziny". Radio Plus Radom (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Samorządowa Karta Praw Rodziny w Radzyniu Podlaskim". Telewizja Polska Lublin (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Samorządowa Karta Praw Rodzin w Powiecie Rawskim". Kochamrawe (in Polish). 1 July 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Rady Powiatu w Rykach – Stanowisko Rady Powiatu Ryckiego w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii gender i "LGBT"". Rady Powiatu Ryckiego (in Polish). 30 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Skrobisz, Jacek (13 February 2020). "Powiat sztumski. Radni przyjęli Samorządową Kartę Praw Rodzin. Powstała "Strefa Wolna od LGBT"?". Portal na Plus (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Nr 1/2019 w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Powiat Świdnicki (in Polish). 2 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Rezolucja nr 1.2019 Rady Powiatu Tarnowskiego z dnia 30 kwietnia 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 30 April 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Pitoń, Angelika (30 December 2019). "Podhale przyjęło Samorządową Kartę Praw Rodzin. "Jesteśmy to winni papieżowi"". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Nr XVIII/144/2020 Rady Powiatu w Tomaszowie Mazowieckim z dnia 27 lutego 2020 r. w sprawie przyjęcia przez Powiat Tomaszowski Samorządowej Karty Praw Rodzin". Powiat Tomaszowski (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Rybczyński, Zbigniew (3 July 2019). "Radni Powiatu Wieluńskiego w obronie praw rodziny. Przyjęto dokument Instytutu Ordo Iuris". Wieluń Nasze Miasto (in Polish). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Rezolucja Rady Powiatu Włoszczowskiego z dnia 16 września 2019 r. w sprawie sprzeciwu wobec promocji i prób wprowadzania ideologii "LGBT" w życiu publicznym" (PDF). Rady Powiatu Włoszczowskiego (in Polish). 16 September 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała Nr VIII/90/2019 Rady Powiatu w Zamościu z dnia 26 czerwca 2019 roku w sprawie przyjęcia Stanowiska Rady Powiatu w Zamościu w sprawie powstrzymania promowania ideologii "LGBT"". Rady Powiatu w Zamościu (in Polish). 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Rezolucja nr 1.2019 Rady Gminy Gromnik z dnia 27 września 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 27 September 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr X/78/2019 Rady Gminy Istebna z dnia 2 września 2019 r. w sprawie podjęcia deklaracji w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Gminy Istebna (in Polish). 2 September 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Deklaracja w sprawie sprzeciwu wobec wprowadzenia ideologii "LGBT" do wspólnot samorządowych". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 30 May 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr VI/51/2019 Rady Gminy Klwów z dnia 17 czerwca 2019 r. w sprawie: podjęcia deklaracji – "Gmina Klwów wolna od ideologii "LGBT""" (PDF). Rady Gminy Klwów (in Polish). 17 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Załącznik nr 14 – głosowanie imienne – Podjęcie uchwały Rady Miasta Kraśnik w sprawie przyjęcia stanowiska dotyczącego powstrzymania ideologii LGBT przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Miasta Kraśnik (in Polish). 3 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Domagała, Małgorzata (29 April 2021). "Kraśnik odrzucił uchwałę "przeciw ideologii LGBT". Motywacją były fundusze norweskie". Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Uchwała nr V/52/2019 Rady Gminy Lipinki z dnia 12 kwietnia 2019 r. w sprawie podjęcia deklaracji "Gmina Lipinki wolna od ideologii "LGBT""". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 12 April 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr 64/VIII/2019 Rady Gminy w Łososinie Dolnej z dnia 31 maja 2019 r. w sprawie przyjęcia Rezolucji dotyczącej powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową oraz ataków na Polski Kościół i obrażania uczuć religijnych ludzi wierzących". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 31 May 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr XI/93/2019 Rady Gminy Niebylec z dnia 25 września 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT"" (PDF). Rady Gminy Niebylec (in Polish). 25 September 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Gminy Serniki w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Gminy Serniki (in Polish). 21 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Sąd zdecydował - kolejna uchwała anty-LGBT unieważniona. Dotyczyła gminy Serniki". MSN (in Polish). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Sąd unieważnił uchwałę anty-LGBT podjętą przez gminę Serniki. "Ma charakter dyskryminujący"". Onet.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała IX/60/2019 Rady Gminy Szerzyny z dnia 4 czerwca 2019 roku zawierająca Deklarację w sprawie sprzeciwu wobec wprowadzenia ideologi "LGBT" do wspólnot samorządowych". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 4 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Uchwała nr VIII/63/19 z dnia 18 czerwca 2019 r. w sprawie stanowiska Rady Gminy Trzebieszów dotyczącego wprowadzania do wspólnot samorządowych ideologii "LGBT"". Rady Gminy Trzebieszów (in Polish). 18 June 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Rezolucja nr 2/2019 Rady Miejskiej w Tuchowie z dnia 29 maja 2019 r. w sprawie przyjęcia rezolucji dotyczącej powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT+" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Biuletyny Informacji Publicznej Województwa Małopolskiego (in Polish). 29 May 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Gminy Tuszów Narodowy przyjęte na V sesji Rady Gminy Tuszów Narodowy w dniu 29 marca 2019 roku w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Gminy Tuszów Narodowy (in Polish). 29 March 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Miejskiej w Urzędowie z dnia 28 marca 2019 r. w sprawie powstrzymania ideologii "LGBT" przez wspólnotę samorządową". Rady Miejskiej w Urzędowie (in Polish). 28 March 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Stanowisko Rady Gminy Zakrzówek "Zakrzówek – gminą wolną od ideologii LGBT"". Rady Gminy Zakrzówek (in Polish). 22 May 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Gmina Skierniewice: Rada mówi stanowcze nie dla LGBT". Gmina Skierniewice (in Polish). Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Zaskakująca decyzja. Wojewoda z PiS uchylił Kartę Praw Rodziny". oko.press. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Polish newspaper to issue 'LGBT-free zone' stickers". BBC News. 18 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Conservative Polish magazine issues 'LGBT-free zone' stickers". Reuters. 24 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Polish Court Rebukes "LGBT-Free Zone" Stickers". Human Rights Watch. 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Polish magazine dismisses court ruling on 'LGBT-free zone' stickers". Politico. 26 July 2019.

- ^ Maher, Jake (26 August 2019). "Carnegie Hall Concert Linked To Anti-LGBT Magazine Canceled". Newsweek.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim (26 August 2019). "Group connected to 'LGBT-Free Zone' newspaper cancels Carnegie Hall event". NBC News.

- ^ "Polish city holds first LGBTQ equality march despite far-right violence". CNN. 21 July 2019.

- ^ "Right-wing Polish magazine slammed for anti-LGBT stickers". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. 24 July 2019. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Dzwonnik, Maciej (23 July 2019). ""Każdy równy, wszyscy różni". W Gdańsku odbył się protest przeciwko nienawiści" ["Everyone is equal, everyone is different": A protest against hatred took place in Gdansk]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Tricity.

- ^ ""Strefa wolna od stref" - manifestacja przeciwko nienawiści, w geście solidarności z LGBT w Gdańsku" ["Zone free of zones" – a manifestation against hatred, in a gesture of solidarity with LGBT in Gdansk]. Dziennik Baltycki (in Polish). 23 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Solidarni z Białymstokiem. Marsze, zbiórki i #TęczowaŚroda" [Solidarity with Bialystok: Marches, rebounds and #TęczowaŚroda]. Polityka (in Polish). 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Szczecin - strefa wolna od nienawiści! W odpowiedzi na tę furię, ten rynsztok" [Szczecin – a zone free from hatred! In response to this fury, this gutter]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Łódź razem z Białymstokiem. Rozdano wlepki "strefa wolna od nienawiści", będzie pikieta" [Łódź together with Białystok: "Hate Free Zone" stickers were distributed, there will be a picket]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Right-wing Polish magazine issues anti-LGBT stickers". Bangkok Post. 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Samorządy przyjmują tak zwane uchwały anty-LGBT" [Local governments adopt anti-LGBT resolutions]. TVN24 (in Polish). 25 July 2019.

- ^ "Ustawy regionów "wolnych od LGBT" są niezgodne z prawem" [The laws of "LGBT free" regions are unlawful]. Queer.pl (in Polish). 22 July 2019.

- ^ Capon, Tom (18 July 2019). "Polish newspaper is handing out 'LGBT-free zone' stickers". Gay Star News.

- ^ ""Gazeta Polska" drukuje naklejki "Strefa wolna od LGBT". Czy ktoś w redakcji słyszał o nazistach?" ["Gazeta Polska" prints "LGBT free zone" stickers. Has anyone in the editorial heard about the Nazis?]. Gazeta.pl (in Polish). 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Polnisches Magazin verteilt Aufkleber "LGBT-freie Zone"" [Polish magazine distributed "LGBT-free zone" stickers]. Queer.de (in German). 18 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fitzsimons, Tim (19 July 2019). "Polish magazine criticized for planning 'LGBT-free zone' stickers". NBC News.

While conservative social media users cheered the move on Twitter and on Facebook, many liberal Poles connected the effort to create "LGBT-free" zones to Nazi efforts to create zones free of Jews.

- ^ "Polonia, botte e insulti al gay-pride di Bialystok" [Poland, beatings and insults to the gay pride of Bialystok]. la Repubblica (in Italian). 21 July 2019.

- ^ "RPO o "Strefie wolnej od LGBT": Polsce grozi dyskryminacja na rynku usług" [RPO on the "LGBT Free Zone": Poland is facing discrimination in the services market]. Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). 5 August 2019.

- ^ Łucyan, Magda (19 July 2019). "Naklejki "Strefa wolna od LGBT". Komentarz ambasador i odpowiedź rządu" [Newspaper promotes stickers with the words "LGBT free zone": US ambassador "disappointed and worried"]. TVN24 (in Polish).

- ^ "The fight against Poland's 'LGBT free zones'". BBC Radio 4. 21 March 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Polish couple hand out rainbow masks to fight country's LGBTQI-free zones". Star Observer. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ "Stars sign open letter supporting Polish LGBT rights". BBC News. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Światowi twórcy kultury stają w obronie osób LGBT w Polsce. Powstał otwarty list do przedstawicieli Unii Europejskiej". MSN Wiadomości (in Polish). 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "LGBT+ Community in Poland: a Letter of Solidarity and Protest". Gazeta Wyborcza. 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Biden: nigdzie na świecie nie ma miejsca na "strefy wolne od LGBT"" (in Polish). Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Sitnicka, Dominika (21 September 2020). "Atlas Nienawiści nominowany do Nagrody im. Sacharowa". oko.press. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Picheta, Rob; Kottasová, Ivana (October 2020). "In Poland's 'LGBT-free zones,' existing is an act of defiance". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Country Ranking | Rainbow Europe". www.rainbow-europe.org. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wądołowska, Agnieszka (3 June 2020). "European Commission intervenes on "LGBT free zones" in Poland". Notes From Poland. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ euronews, July 2020

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jędrysik, Miłada (16 September 2020). "Ursula von der Layen w PE o strefach wolnych od LGBT". oko.press. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Parliament declares the European Union an LGBTIQ Freedom Zone | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Francuska gmina zrywa partnerstwo z Tuchowem. Powodem uchwała o LGBT". Onet.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Une ville du Loiret rompt ses relations avec sa jumelle polonaise après ses arrêtés homophobes". Ouest-France (in French). 17 February 2020.

- ^ Hajzler, Yacha (16 February 2020). "Homophobie : Saint-Jean-de-Braye rompt ses relations avec la ville jumelle polonaise de Tuchów". France 3 (in French).

- ^ "Kolejna francuska gmina zawiesza partnerstwo z polskim miastem ze "strefą wolną od LGBT"". TOK FM (in Polish). 21 February 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Francuski region zawiesza współpracę z Małopolską. "Jawnie homofobiczna deklaracja"". Onet.pl (in Polish). 25 February 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Rivaud, François-Xavier (2 March 2020). "Zones anti-LGBT : la région Centre - Val-de-Loire rompt avec la Pologne". Le Parisien (in French). Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ ""Zones anti-LGBT" : la région Centre-Val de Loire suspend sa coopération avec Malopolska en Pologne". La République du Centre (in French). 25 February 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Pitoń, Angelika (20 May 2020). "Niemcy zrywają współpracę z Nowym Sączem. Powód: akceptacja dla projektu Ordo Iuris". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (16 July 2020). "Dutch town ends ties with Polish twin declared 'gay-free zone'". The Guardian.

- ^ Frankowska, Maria (2 March 2020). "Douai zawiesza współpracę z Puławami za strefę anty LGBT. Mer: "Przemoc zaczyna się od słów"". OKO.press (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Irlandzkie miasto zrywa współpracę z Nową Dębą z powodu uchwały przeciw LGBT" (in Polish). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Belgijska gmina zawiesza 20-letnią współpracę z Dębicą" (in Polish). Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Wieliński, Bartosz T. (29 July 2020). "EU cuts funding to Polish cities declaring themselves "LGBT-free zones"". Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ "Polish Towns That Declared Themselves 'L.G.B.T. Free' Are Denied E.U. Funds". The New York Times. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Charlish, Alan; Florkiewicz, Pawel; Plucinska, Joanna (18 August 2020). "Polish 'LGBT-free' town gets state financing after EU funds cut". Reuters.

- ^ "Gminy "wolne od LGBT" nie dostaną pieniędzy z funduszy norweskich. Kraśnik wycofa uchwałę?" (in Polish). 20 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "MSZ Norwegii: gminy "wolne od LGBT" nie dostaną funduszy norweskich". oko.press. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Igrzyska Europejskie 2023. Europosłowie przeciwni organizacji zawodów sportowych w "homofobicznej" Małopolsce" (in Polish). 23 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Savage, Rachel (8 October 2020). "Lawmakers criticise hosting of 2023 Games in Polish 'LGBT-free zone'". Reuters.

External links[]

- Atlas nienawiści (Atlas of Hate) - Map of anti-LGBT ideology Polish government resolutions

- Tu nie chodzi o ludzi(This is not about people) - a documentary film presenting fragments of political debates on so-called anti-LGBT resolutions

- Knecht, Tomasz (2020). "Idea miast partnerskich wobec wybranych uchwał samorządowych w Polsce w latach 2019–2020" [The idea of sister cities in view of selected local government resolutions in Poland in the years 2019–2020]. Rocznik Europeistyczny. 5: 123–141. doi:10.19195/2450-274X.5.8.

- 2019 in LGBT history

- 2019 in Poland

- 2019 in law

- 2020 in law

- 2020 in LGBT history

- 2020 in Poland

- 2020 in the European Union

- Anti-LGBT sentiment

- Censorship in Poland

- Controversies in Poland

- Discrimination against LGBT people

- Euroscepticism in Poland

- Far-right politics in Poland

- LGBT-related controversies

- LGBT rights in Poland

- Legal history of Poland

- Moral panic

- Polish law

- Political controversies in Europe

- Right-wing populism in Poland

- Scares

- 2010s neologisms

- Censorship of LGBT issues