Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew | |||

|---|---|---|---|

李光耀 | |||

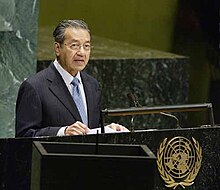

Lee in 1975 | |||

| 1st Prime Minister of Singapore | |||

| In office 5 June 1959 – 27 November 1990 | |||

| President |

| ||

| Deputy |

| ||

| Preceded by | Lim Yew Hock (as Chief Minister) | ||

| Succeeded by | Goh Chok Tong | ||

| Member of Parliament for Tanjong Pagar | |||

| In office 22 April 1955 – 23 March 2015 | |||

| Constituency | Tanjong Pagar (Assembly) (1955–65) Tanjong Pagar SMC (1965–91) Tanjong Pagar GRC (1991–2015) | ||

| |||

| |||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | Harry Lee Kuan Yew 16 September 1923 Singapore, Straits Settlements | ||

| Died | 23 March 2015 (aged 91) Singapore | ||

| Cause of death | Pneumonia | ||

| Political party | People's Action Party (1954–2015) | ||

| Spouse(s) | Kwa Geok Choo

(m. 1950; died 2010) | ||

| Children |

| ||

| Parents |

| ||

| Education | Telok Kurau English School | ||

| Alma mater |

| ||

| Signature |  | ||

| Lee Kuan Yew | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Lee's name in Chinese characters | |||

| Chinese | 李光耀 | ||

| |||

Lee Kuan Yew (born Harry Lee Kuan Yew; 16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), often referred to by his initials LKY and sometimes known in his earlier years as Harry Lee, was a Singaporean statesman and lawyer who served as Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990, and is recognised as the nation's founding father.[2][3] He was one of the founders of the People's Action Party, which has ruled the country continuously since independence.

Lee was born in Singapore during British colonial rule, which was part of the Straits Settlements. He attained top grades in his early education, gaining a scholarship and admission to Raffles College. During the Japanese occupation, Lee worked in private enterprises and as an administration service officer for the propaganda office. After the war, Lee initially attended the London School of Economics, but transferred to Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, graduating with starred-first-class honours in law in 1947. He became a barrister of the Middle Temple in 1950 and returned to Singapore, and began campaigning for the United Kingdom to relinquish its colonial rule.

Lee co-founded the People's Action Party in 1954 and won his first seat in the Tanjong Pagar division in the 1955 election. He became the de facto opposition leader in the legislature to chief ministers David Marshall and Lim Yew Hock. Lee led his party to its first electoral victory in the 1959 election, and was appointed as the state's first prime minister. To attain complete self-rule from Britain, Lee campaigned for a merger with other former British territories in a national referendum to form Malaysia in 1963. Racial strife and ideological differences led to Singapore's separation from the federation to become a sovereign city-state in 1965.

With overwhelming parliamentary control at every election, Lee oversaw Singapore's transformation into a developed country with a high-income economy within a single generation. In the process, he forged a system of meritocratic, highly effective and anti-corrupt government and civil service. Lee eschewed populist policies in favour of long-term social and economic planning. He championed meritocracy[4] and multiracialism[5][6] as governing principles, making English the lingua franca[7] to integrate its immigrant society and to facilitate trade with the world, whilst mandating bilingualism in schools to preserve students' mother tongue and ethnic identity.[7] Lee stepped down as prime minister in 1990, but remained in the Cabinet under his successors, holding the appointments of senior minister until 2004, then minister mentor until 2011. He died of pneumonia on 23 March 2015, aged 91. In a week of national mourning, about 1.7 million Singaporean residents as well as world leaders paid tribute to him at his lying-in-state at Parliament House and community tribute sites.

A stalwart supporter of so-called Asian values, Lee's rule was sometimes criticised by various observers from the liberal democracies of the West in response.[8] While elections are free, critics had accused him of curtailing press freedoms, limits on public protests, restricting labour movements from strike action, and bringing defamation lawsuits against some political opponents.[9][10] Nevertheless, his beliefs such as government transparency have been adhered to by successive administrations of the governing party, and Singapore continues to be considered one of the least corrupt countries compared to the rest of the world.[11]

Early life[]

Childhood and early education[]

Lee was born at home on 16 September 1923, as the first child to Lee Chin Koon and Chua Jim Neo, at 92 Kampong Java Road in Singapore.[12] The island was part of the Straits Settlements under British colonial rule, and both of Lee's parents were English-educated third-generation Straits Chinese.[13] Lee's paternal great-grandfather, Lee Bok Boon, was of Hakka descent and emigrated from Dabu County, Guangdong, to the Straits Settlements in 1862.[14][15] Lee's parents named him 'Kuan Yew',[a] meaning 'light and brightness', with an alternate meaning 'bringing great glory to one's ancestors'. Lee's paternal grandfather Lee Hoon Leong, who was described as "especially westernised", had worked on British ships as a purser, and hence gave Lee the Western name 'Harry'.[16] While the family spoke English as its first language, Lee also learned Malay and Cantonese; the latter he picked up from the family maid.[12][17] Lee would have three brothers and one sister, all of whom lived till old age.[18]

Lee was not close to his father, who worked as a storekeeper within the Shell Oil Company and had a gambling addiction. His mother Chua would often stand up against her husband for his poor fiscal management and parenting skills, with the result that Lee greatly admired her.[19] The family was considered prosperous with a high social standing compared to recent immigrants and had the expenses to hire servants.[20] During the Great Depression the family fortunes declined considerably, though Lee's father retained his job at Shell, was later promoted to manager, and was assigned a car, chauffeur and house.[12] Later in life, Lee described his father as a man with a nasty temper and credited his mother with holding the family together and refusing to pawn her family jewellery to fund her husband's gambling addiction.[21] She would later use the savings to help pay for Lee's education.[22]

In 1930, Lee enrolled at Telok Kurau English School where he spent six years of his primary education.[23][24] Attending Raffles Institution in 1935, Lee had difficulties keeping up with his studies, but his results improved by Junior A (Secondary 3) and he topped the Junior Cambridge examinations.[25] He also joined the Scouts and partook in several physical activities and debates.[26] Lee was the top scorer in the Senior Cambridge examinations in 1940 across the Straits Settlements and Malaya, gaining the John Anderson scholarship to attend Raffles College.[b] During the prize-awarding ceremony, Lee met his future wife Kwa Geok Choo for the first time, who was the only girl at the school.[25] His subsequent university studies at Raffles College were disrupted by the onset of World War II in Asia, with the school being converted into a medical facility in 1941. The war arrived in December of that year and following the British surrender in February 1942, the Japanese occupation of Singapore began.[27]

World War II[]

In the early days of the occupation, the Japanese military ordered all Chinese to report for a screening as part of the Sook Ching operation to purge undesirable elements. By his own account, Lee followed suit as he feared getting caught by the Kempetai (military police), reporting to Jalan Besar stadium with a friend, Koh Teong Koo. Koh's dormitory was within the perimeter setup by the Japanese and Lee spent the night there with him. He attempted to leave the next morning but was ordered by a guard to join a group of already segregated men. Sensing that something was amiss, he requested for permission to collect his clothes first, and the guard agreed. Lee spent a second night in the dormitory before successfully leaving the site the next day when a different guard cleared him through.[28] He would later learn that the group of men were likely taken to the beach and executed.[29]

Lee obtained his Japanese language proficiency certificate in August 1942 after a three months' course, working first as a clerk in a friend's company and then the Kumiai, which controlled essential items.[30] He got a job with the Japanese propaganda department (Hōdōbu) in late 1943 as an English specialist. Working at the top of the Cathay Building, he was assigned to listen to Allied radio stations for Morse code signals.[31] Some sources say he may have passed information to the British while working there, but this is not confirmed.[32][33] By late 1944, Lee knew Japan had suffered several major defeats. Anticipating fierce fighting should the British re-invade, he made plans to move to a farm on the Cameron Highlands with his family. He was tipped off by a contact that the Kempetai suspected him, and decided to abandon the plan.[34] He engaged in private enterprises and black market sales for the rest of the war.[35]

The Japanese occupation had a profound impact on Lee, who recalled being slapped and forced to kneel for failing to bow to a Japanese soldier.[36] In a radio broadcast made in 1961, Lee said he "emerged [from the war] determined that no one—neither Japanese nor British—had the right to push and kick us around ... (and) that we could govern ourselves."[37] It also influenced his perceptions of raw power and the effectiveness of harsh punishment in deterring crime.[38]

University, marriage and politics[]

Lee chose not to return to Raffles College after the war, deciding to pursue a Queen's Scholarship in the United Kingdom.[19] On 16 September 1946, his 23rd birthday, Lee sailed from Singapore on the MV Britannic, which was carrying demobilised British troops home, arriving on 3 October.[39] The admissions period had closed, but he convinced the dean of the law faculty, Hughes Parry, at the London School of Economics to enroll him. Life in the British capital was difficult and Lee greatly disliked his time there.[40][41] Upon a lecturer's advice, he visited Cambridge in November and met a former Raffles College student, who introduced him to W. S. Thatcher, Censor of Fitzwilliam House. He was admitted into the following year's Lent term and matriculated in January 1947, reading law at Fitzwilliam College.[42]

Prior to his departure from Singapore, Lee had begun a relationship with Kwa, whom he had kept in contact during the war. Kwa gained her Queen's Scholarship in 1947, but the Colonial Office was unable to allocate a university placing until 1948. Lee intervened with the school to admit and bring forward her matriculation, and she arrived in October of that year.[43] They married in secret at Stratford-upon-Avon in December.[19] Lee graduated First Class in both parts of the Tripos with an exceptional Starred-First for Part II Law in 1949 with Kwa. As the top student of his cohort, he was awarded the Fitzwilliam's Whitlock Prize; Lee was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1950.[42]

If you value fairness and social justice, not only to the people of Britain but also to the millions of British subjects in the colonies, return another Labour government.

Lee to voters in the Totnes constituency.[44]

During his studies, Lee's political convictions and anti-colonial sentiments had been hardened by personal experiences and an increasing belief that the British were ruling Singapore for their own benefit. He supported the Labour Party against the Conservatives whom he perceived as opposing decolonisation.[45] In the leadup to the 1950 United Kingdom general election, Lee engaged in politics for the first time and actively campaigned for a friend, David Widdicombe in Totnes constituency, driving Widdicombe around in a lorry and delivering several speeches on his behalf. The Labour Party retained power, though Widdicombe lost the election.[46]

Before returning to Singapore, Lee dropped his English name, Harry.[c] Notwithstanding, even until the end of his life, old friends and relatives referred to him as Harry.[48]

Early career (1951–1955)[]

Litigation practice and Fajar trial[]

Lee and his wife arrived back in Singapore on 1 August 1950 on the MS Willem Ruys.[49][50] He joined the Laycock and Ong law firm founded by British lawyer John Laycock, which paid a monthly salary of $500.[51] Laycock was also a co-founder of the pro-British and colonial Progressive Party and Lee acted as an election agent for the party during the 1951 legislative council election.[52] Lee was called to the Singapore bar on 7 August 1951.[53]

During the postal union strike in May 1952, Lee successfully negotiated a settlement which would mark his first step into the labour movement.[54] In due course, Lee represented nearly fifty trade unions and associations against the British authorities on a pro bono basis, sometimes asking only for a token sum in payment.[55] The disputes often centered around wages and Laycock eventually requested Lee to cease taking on such cases as it was hurting the firm.[56][57] Activists and clients said that Lee was likely preparing to enter politics and saw his work as a means to burnish his 'pro-labour' credentials among the trade unions, which he later confirmed.[58]

In May 1954, members of the left-wing student group University Socialist Club published an article 'Aggression in Asia' in the club's magazine The Fajar, which condemned "Western aggression", criticised the formation of SEATO, and called Malaya a police state.[59][60] The students were arrested and charged with sedition by the British authorities. The prominent lawyer David Marshall was initially proposed as a defence counsel, which the members quickly rejected as he was against them.[61] Lee became junior counsel to the lead counsel Denis Pritt whom had flown in from Britain. Lee claimed that he had acquired Pritt's services, though this account is disputed by the club president.[62][63] Pritt successfully squashed the charges in two days and both men gained a reputation through the trial, with Lee thereafter becoming a "major leader" of the movement against British rule.[62][64]

During the same year, a group of Chinese high school students had been arrested and subsequently convicted for their roles in the 13 May incident. The students had been protesting the British-imposed National Service Ordinance imposing conscription on Singapore when a riot broke out. Lee agreed to appeal on behalf of the students and again acquired Pritt's services. The colonial government was determined not to have a repeat of the Fajar trial and upheld the sentences. The case nevertheless gave rise to Lee's reputation as a "left-wing lawyer" and marked his first involvement with the Chinese intelligentsia, which he had hitherto not been involved in due to his Chinese illiteracy.[65][66]

Formation of the People's Action Party[]

During his studies in Britain, Lee met Goh Keng Swee and Toh Chin Chye via the Malayan Forum, both whom would later become deputy prime ministers.[67] The forum sought to promote an independent Malaya which included Singapore and met at 44 Bryanston Square in London, later known as Malaya Hall.[68][69] Lee and his contemporaries deliberately avoided the topic of forming a political party as it was regarded by the colonial government at home as an act of subversion. The government had outlawed the Malayan Communist Party in 1948, starting a low intensity conflict known as the Malayan Emergency, with the Special Branch closely monitoring the forum back in Britain for radical students. Lee began work on forming a political party only after returning to Singapore.[70]

Lee had sought to build support among the English-educated, Malay, and Indian communities by taking on cases against the British authorities. In the course of his work, Lee became acquainted with the journalist Sinnathamby Rajaratnam; Abdul Samad Ismail, a writer for the Malay newspaper Utusan Melayu; and Devan Nair; the latter two had been imprisoned for their involvement in the Anti-British League.[71] He next turned his attention to the Chinese-speaking majority and was introduced to Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan, leaders of the influential bus and factories unions. While the unions had been infiltrated by communists, Lee consciously sought their support as he wanted a popular front.[72] With elections approaching in 1955, Lee and his associates debated the name, ideology, and policies of the party they wanted to create at 38 Oxley Road.[73]

The People's Action Party (PAP) was officially inaugurated on 21 November 1954 at the Victoria Memorial Hall. As the party still lacked members, trade union leaders rounded up an estimated audience of 800 to 1,500 supporters.[74] Lee had also invited Tunku Abdul Rahman and Tan Cheng Lock, presidents of the peninsula-based United Malays National Organisation and Malayan Chinese Association to add "leverage" and "prestige" to the event. In his inaugural speech, Lee denounced the British for the slow transition to self-rule, demanded their immediate withdrawal, and announced that the PAP would pursue Malaya-Singapore unification to form a single state. Lee became secretary-general of the party, a post he held until 1992.[75]

1955 legislative assembly election[]

| External image | |

|---|---|

National Archives of Singapore |

In July 1953, Governor John Nicoll initiated the Rendel Commission to review Singapore's political status and provide for a transition to self-rule. The commission created the legislative assembly and opened 25 of 32 seats for direct contest in the upcoming 1955 legislative assembly election, with the governor retaining significant powers and veto rights. The PAP and Labour Front, led by Lee and David Marshall respectively, both criticized the concessions as "inadequate". The PAP faced manpower constraints but decided to prioritise resources and contest four seats as a protest gesture.[76] In a rally speech, Lee said he chose the Tanjong Pagar division as it was a "working class area" and that he did not want to represent "wealthy merchants or landlords".[77]

During the campaigning period, the British press labelled Lee as a "commissar" and accused the PAP of being a "communist-backed party".[78] Democratic Party (DP) challenger Lam Thian also capitalized on Lee's inability to converse in Chinese and repeatedly challenged him to a Chinese debate. Lee's proposal for a multilingual debate was never reciprocated by Thian, though he eventually made his maiden Chinese speech after several hours of coaching.[79][80] On polling day, 2 April, the ruling Progressive Party (PP) captured only four seats, shocking both the British establishment and its opposition. Lee defeated his PP and DP competitors and won Tanjong Pagar, with the PAP winning three of their four contested seats. The Labour Front with ten seats assumed power and Marshall became Singapore's first chief minister. At the counting center at the Victoria Memorial Hall, Lee pledged to work with Marshall.[81]

Lee's relationship with his superior Laycock, a co-founder of the Progressive Party, had deteriorated by 1954. After the election, Laycock never spoke to Lee again, and the two mutually agreed to terminate their partnership in August 1955.[82]

Opposition leader (1955–1959)[]

Hock Lee bus riots[]

Any man in Singapore who wants to carry the Chinese-speaking people with him cannot afford to be anti-Communist. The Chinese are very proud of China. If I had to choose between colonialism and communism, I would vote for communism and so would the great majority.

Lee to an Australian journalist a week before the riot[83]

On 23 April 1955, workers from the Hock Lee Amalgamated Bus Company began a strike under the direction of , leader of the Singapore Buses Workers' Union (SBWU); they had been angered by the company's demands to join a rival union and subsequent sacking of 229 dissenters.[84][85] As SBWU's legal advisor, Lee worked with Marshall's government to negotiate a resolution, which was initially agreed by the SBWU but then reneged on by the company.[86] Seeking to exert greater pressure, Lee, Fong and Lim Chin Siong addressed the strikers on 1 May (May Day), where Lee called the government a "half-past six democracy" and Fong said "bloodshed" was inevitable.[87] Lee also acknowledged in an interview with an Australian journalist that the PAP could not afford to alienate its Chinese base.[83] The strike subsequently escalated into a riot on 12 May, resulting in four deaths and Fong's arrest.[88]

Lee, Marshall and the company agreed on a further resolution on 14 May, which conceded to the strikers' demands of union autonomy and reinstatement of sacked workers.[89] In an emergency legislative assembly sitting on 16 May, Chief Secretary William Goode accused Lee of losing control of the PAP to Lim, whom commanded the Chinese support that the party needed.[86] Lee was constrained between defending the actions of his colleagues and denouncing them, as the latter would break the party's "united front", instead reiterating the PAP's committal to non-violence in seeking to end colonialism.[90] Lee was surprised when Marshall characterized him and the PAP as "decent men" against Goode's accusations and called upon the party to "purge themselves of communists".[86][89]

The riot led the public to perceive the PAP as being led by "young, immature and troublesome politicians", resulting in a shortfall of new members.[91] It deepened the divide within the party's central executive committee between the two factions, with Lee's faction advocating Fabian's brand of socialism for gradual reform and Lim's faction, later described by Fong as "favour(ing) a more radical approach".[92] Lee returned from a vacation in the Cameron Highlands convinced that Lim and Fong's influence were pushing the party toward "political disaster".[83] After consulting his allies Toh Chin Chye, S. Rajaratnam and Byrne, Lee censured the two men privately and demanded they change strategies or leave the party.[93]

Merdeka talks[]

The Labour Front government's conciliatory approach to the Hock Lee strikers led to a drastic increase in strikes thereafter, with an estimated 260 strike-related activities by the end of 1955.[89] In a bid to handle the problem, Marshall created a constitutional crisis by demanding expanded powers and further reforms to the constitution towards the aim of "true self-government". He threatened to resign if these demands were not met.[94] The British feared a further breakdown in order and reluctantly agreed to talks in London. Lee supported Marshall in his efforts, though he initially threatened an opposition boycott over wording disputes in the agreement.[94] Between 1956 and 1958, there would be three rounds of constitutional talks, later colloquially labelled the Merdeka[d] talks.[95]

Lee and Lim Chin Siong represented the PAP as part of Marshall's 13-member delegation to London in April 1956. During the talks, Marshall's demands for independence were repeatedly rejected by Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd; the British distrusted Marshall's ability to tackle the communist threat and wanted to retain control of internal security.[96][97] Lee, Lim and one other Labour Front member eventually decided to depart early over Marshall's refusal to compromise. Before leaving on 22 May, Lee gave a press conference criticising Marshall for his "political ineptitude", receiving widespread media and radio coverage in the British press.[98] Marshall resigned shortly after returning home and was succeeded by Lim Yew Hock as chief minister.[98][e]

The following year in March 1957, Lee was the lone PAP representative in the five-member delegation to London during the second round of talks.[99] He opposed terms banning candidates charged with subversive activities from running in the next election without success.[100] Britain agreed to Singapore's self-governance, with a tripartite Internal Security Council to be established consisting of Singaporean, Malayan and British representatives.[99] The interim agreement was opposed by the party's leftist faction led by Lim C.J., and Marshall whom was now an independent Member for Cairnhill.[99] During the legislative assembly sitting on 26 April, Marshall challenged Lee to seek a fresh mandate from his Tanjong Pagar constituents, which Lee accepted.[101] In the June 1957 by-elections, Lee was reelected with 68.1% of the vote.[102]

Lee returned to London for the third and final talks in May 1958,[103] where it was agreed that Singapore would assume self-governance with a Yang di-Pertuan Negara as head of state, with Britain retaining control of defence and foreign policy.[104] The British House of Lords passed the State of Singapore Act on 24 July 1958, which received royal assent on 1 August, and would become law following the next general election.[105]

Party power struggle[]

| PAP CEC 4 August 1957 election[106][107] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lee's faction | Votes | Leftist faction | Votes |

| Lee Kuan Yew | 1213 | T.T. Rajah | 977 |

| Toh Chin Chye | 1121 | Goh Boon Toh** | 972 |

| Ahmad Ibrahim | 966 | Tan Chong Kin* | 811 |

| Goh Chew Chua | 794 | Ong Chye Ann** | 762 |

| Tann Wee Tiong | 655 | Tan Kong Guan** | 751 |

| Chan Choy Siong | 621 | Chen Say Jame* | 651 |

| * Arrested. ** Arrested and deported to the PRC. | |||

Whilst in London during the first Merdeka talks in April 1956, Lee had discussed the PAP's future with Goh Keng Swee, who was in Britain completing his PhD. Lee lamented to Goh that the PAP "had been captured by the communists". When the Chinese middle schools riots later that year captured international attention, the Lim Yew Hock government launched a purge on 27 October, arresting 259 suspected "leftists" including Lim Chin Siong and other members of his faction.[108] Lee privately endorsed the purge while defending his arrested colleagues publicly, which he described as "going through the motions".[93] Lim C.S.'s brother, Lim Chin Joo, took over the "leftist" faction in the absence of its leaders.[109]

During the PAP central executive committee (CEC) elections on 4 August 1957, the leftists captured six seats to Lee and his associates' dismay, who were prepared to concede only four seats.[110] Lee refused to allow his allies to assume their appointments, citing that his faction had "lost their moral right" to enforce the party's original founding philosophy.[111] Overtures were repeatedly made to Lee to remain in his post, to which he declined.[110] The Lim Y.H. government became alarmed and ordered the Special Branch to arrest the leftist leaders on 22 August, subsequently banishing three to the People's Republic of China.[107][112] Lee was restored as secretary-general on 20 October and later blamed the attempted takeover on lax admission rules to the party.[113][114] The incident made Lee permanently distrustful of the leftists and he began searching for new candidates that would appeal to the Chinese electorate and yet be loyal to him.[112][113] The identify of the person who planned the takeover remains disputed.[115]

On 23 November 1958, the party constitution was amended to implement a cadre system.[114] The rights to vote in party elections and run for office were revoked from ordinary party members, whom now had to seek approval from the CEC to be a cadre and regain these privileges.[116] The criteria to be a cadre was set intentionally high for even the lowest tier of membership, automatically disqualifying students and illiterate persons.[112] Lee was influenced by the Vatican system where the pope pre-selects its cardinals, while party chairman Toh Chin Chye credited communist organisations for the idea.[117]

1957 and 1959 elections[]

In the lead-up to the 1957 City Council election in December, a Hokkien-speaking candidate, Ong Eng Guan, became the PAP's new face to the Chinese electorate and gained immense popularity.[112] The 32-seat city council's functions were restricted to up-keeping public amenities within city limits, but party leaders decided to contest as a "dry run" for the upcoming general election.[118] Lee limited the PAP to contesting 14 seats to avoid provoking the Lim Yew Hock government and formed an electoral pact with the Labour Front and United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) to jointly tackle the new Liberal Socialist Party.[f][120] The PAP campaigned on a slogan to "sweep the city clean"[119] and emerged with 13 seats, allowing it to form a minority administration with UMNO's support. Lee and the rest of the CEC unanimously endorsed Ong to become mayor.[118] The election also marked the debut of Marshall's newly established Workers' Party, which won four seats.[121]

| External image | |

|---|---|

National Heritage Board |

Early in 1959, Communications and Works Minister Francis Thomas received evidence of corruption on Education Minister Chew Swee Kee. Thomas brought the evidence to Lee after the chief minister dismissed the matter.[122] Lee tabled a motion in the assembly on 17 February, which forced Chew's resignation.[122] As the expiry of the assembly's term approached, the PAP was initially split on whether to capture power but Lee chose to proceed.[123] While picking the candidates, Lee deliberately chose people from different racial and education backgrounds to repair the party's image of being run by intellectuals.[124] In the 1959 general election held on 30 May 1959, the PAP won a landslide victory with 43 of the 51 seats, though with only 53.4% of the popular vote which Lee noted.[124][125]

The PAP's victory reportedly created a dilemma within the 12-member CEC as there was no formal process in place to choose a prime minister-elect.[126] A vote was purportedly held between Lee and Ong Eng Guan and after both men received six votes, party chairman Toh Chin Chye cast the tie-breaking vote for Lee.[127] When interviewed nearly five decades later, Toh and one other party member recalled the vote, but Lee and several others denied the account.[127] Lee was summoned by Governor William Goode to form a new government on 1 June, to which he requested the release of arrested PAP members.[128] On 3 June, Singapore became a self-governing state, ending 140 years of direct British rule.[128] Lee was sworn in as Prime Minister of Singapore on 5 June at City Hall, along with the rest of his Cabinet.[128]

Prime Minister, State of Singapore (1959–1963)[]

First years in power[]

Lee's first speech as prime minister to a 50,000-strong audience at the Padang sought to dampen his supporters' euphoria of the PAP's electoral win.[125] In the first month of Lee taking power, Singapore experienced an economic slump as foreign capital fell and Western businesses and expatriates left for Kuala Lumpur in Malaya, fearing the new government's anti-colonial zeal.[125] As part of an 'anti-yellow culture' drive, Lee banned jukeboxes and pinball machines, while the police under Home Affairs Minister Ong Pang Boon raided pubs and pornography publications.[g][129] The government cracked down on secret societies, prostitution and other illegal activities, with TIME magazine later reporting that a full week passed without "kidnapping, extortion or gangland rumble(s)" for the first time.[129] Lee also spearheaded several 'mobilisation campaigns' to clean the city, introduced air-conditioning to government offices, and slashed the salaries of civil servants. The last act provoked anger from the sector, which Lee justified as necessary to balance the budget.[130]

In February 1960, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) superseded the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) and assumed responsibility of public housing. With strong government support, the HDB under chairman Lim Kim San completed more flats in three years than its predecessor did in thirty-two.[131] Government expenditure for public utilities, healthcare and education also increased significantly.[131] By the end of the year, however, unemployment began to rise drastically as the economy slowed. Lee reversed anti-colonial policies and launched a five-year plan to build new industries, seeking to attract foreign investors and rival Hong Kong.[132][133] Jurong, a swampland to the island's western coast was chosen to be the site of a new industrial estate and would house steel mills, shipyards, and oil refineries, though Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee was initially worried the venture would fail.[134]

The government promoted multiculturalism by recognizing Malay, English, Tamil and Chinese as the official languages of the new state and sought to create a new national Malayan identity. The Ministry of Culture under S. Rajaratnam held free outdoor concerts with every ethnic race represented in the performances.[135] Lee also introduced the People's Association, a government-linked organisation to run community centers and youth clubs, with its leaders trained to spread the PAP's ideology.[135] Youth unemployment was alleviated by the establishment of work brigades.[135]

PAP split of 1961[]

Lee took measures to secure his position in the aftermath of the 1957 party elections. In 1959, he delayed the release of leftist PAP leaders arrested under the former Labour Front government from 2 to 4 June, after the PAP victory rally.[136] Five of the former arrestees,[h] Lim Chin Siong, Fong Swee Suan, Devan Nair, James Puthucheary and S Woodhull, were appointed to parliamentary secretary roles which lacked influence over policy making.[128][138] Lim and Fong still led influential unions and clashed with Lee when the government sought to create a centralised labour union in the first half of 1960.[139] Trouble also arose from former mayor and Minister of National Development Ong Eng Guan, who Lee had appointed in recognition of Ong's contribution to the PAP's electoral win.[139][140] Ong's relocation of his ministry to his Hong Lim stronghold and continued castigation of the British and civil servants was regarded by his colleagues as disruptive and Lee removed several portfolios from Ong's purview in February 1960.[137][140]

In the party conference on 18 June 1960, Ong filed "16 resolutions" against the leadership, accusing Lee of failing to seek party consensus when deciding policy, not adhering to anti-colonialism and suspending left-wing unions.[141] Lee regarded it as a move to split the party and reacted forcefully with his allies. The party central executive committee unanimously voted to expel Ong the next day.[142] Ong resigned his legislative assembly seat in December, precipitating the Hong Lim by-election on 29 April 1961 which he stood as an independent against a PAP candidate and won, later establishing the United People's Party.[137][143] The death of the PAP assemblyman for Anson that April triggered a second by-election to be held on 15 July. For the first time, Lim's faction openly revolted against Lee and endorsed Workers' Party chairman David Marshall, who captured the seat from the PAP.[137][144]

Lee assumed responsibility for the two by-election defeats and submitted his resignation to party chairman Toh Chin Chye on 17 July. Toh rejected it and upheld Lee's mandate.[145] Lee moved a motion of confidence in his own government in the early hours of 21 July after a thirteen-hour debate which had begun the preceding day, narrowly surviving it with 27 "Ayes", 8 "Noes" and 16 abstentions.[146] The PAP now commanded a single seat majority in the 51-seat assembly after 13 of its members had abstained.[147] Lee expelled the 13 who had broken ranks in addition to Lim, Fong and Woodhull.[147]

Leadup to referendum and merger[]

Lee and his colleagues believed that Singapore could only survive through merger with Malaya and was unwilling to call for complete independence.[148] Merger would allow goods to be exported to the peninsula under a common market, while devolving unpopular internal security measures to Kuala Lumpur.[148][149] Malaya's ruling Alliance Party coalition dominated by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) had repeatedly opposed the scheme and was apprehensive that Singapore's Chinese majority would reduce 'Malay political supremacy'.[150] Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman backtracked after the PAP's Hong Lim by-election defeat, fearing a "pro-communist government" in Singapore should Lee fall from power.[149] On 27 May 1961, Tunku announced that Malaya, Singapore, and the British colonies of North Borneo and Sarawak should pursue "political and economic cooperation".[149] Lee endorsed the program six days later and commenced negotiations on the formation of Malaysia.[149]

In August 1961, Lee and Tunku agreed that Singapore's defence, foreign affairs and internal security would be transferred to the federal government, while education and labour policy remained with the state government.[149][151] Lim Chin Siong and his supporters saw Lee's ceding control of internal security—then controlled by the Internal Security Council with British, Malayan, Singaporean representatives—to the federal government as a threat as Tunku was convinced they were communists.[149] In a meeting with British Commissioner General Lord Selkirk, Selkirk reaffirmed that the British would not suspend Singapore's constitution should Lee be voted out.[149] Lee saw the meeting as a British endorsement of Lim and accused it as a plot against his government.[152] On 13 August, Lim founded the Barisan Sosialis and became its secretary-general, with 35 of 51 branches of the PAP defecting.[147][153] Lee anticipated a Barisan win in the next election and saw 'independence through merger' as the only means for the PAP to retain power.[150]

Beginning on 13 September 1961, Lee gave twelve multilingual radio speeches outlining the benefits of merger in what he called the 'Battle for Merger'. The speeches proved to be a massive success for Lee's campaign, while Barisan's demands for equal airtime were rejected.[154] Lee employed full use of state resources to suppress his opponents by revoking the Barisan's printing permits, banning or relocating its rallies, and purging its supporters from the government, while the judiciary and police engaged to "obstruct, provoke and isolate" the party.[155] The Barisan lambasted Lee for securing only 15 seats in the Malaysian parliament for Singapore in contrast to North Borneo (16) and Sarawak (24), despite both having a combined population well below Singapore's 1.7 million.[156] Singapore citizens would also be categorized as "nationals" and not be granted Malaysian citizenship.[156][157] On 6 December, the legislative assembly voted 33–0 in favour of the agreements struck by Lee and Tunku, which the Barisan boycotted.[158]

A referendum for merger was scheduled for 1 September 1962. Lee ensured that the ballot lacked a "no" option, with all three options having varying terms for admission into Malaysia.[156] The ballot was crafted by Lee and Goh Keng Swee to capitalise on a mistake which the Barisan had made the previous year. The Barisan had inadvertently endorsed merger under terms "like Penang" (a state of Malaya) with full citizenship rights, not realising that Malayan law entitled only a native-born to qualify for automatic citizenship, which would disenfranchise nearly one third of those eligible to vote;[159] it issued a clarification but never recovered from the mistake.[160] Lee placed the flag of Singapore alongside option A with the terms of Singapore retaining control of education and labour policy, while portraying the Barisan's choice as option B favouring entry into the federation with no special rights, next to the flag of Penang.[161] When Lim called for his supporters to submit blank votes, Lee countered that blank votes would count as a vote for the majority choice. 71% eventually voted for option A, while 26% cast blank votes.[162] In November, Lee embarked on a ten-month visit to all fifty-one constituencies, prioritizing those with the highest count of blank votes.[163]

Operation Coldstore detentions[]

The Malayan government considered the arrests of Singapore's left-wing groups as non-negotiable for the formation of Malaysia.[164][165] Tunku felt that Lee lacked the initiative to suppress "pro-communist elements" and warned that a Malay-led dictatorship would be instated to prevent a "socialist majority" in the next Malayan election.[158] As the Malayans increased pressure on the Internal Security Council (ISC) to take action, Lee began supporting the idea of a purge in March 1962.[166] The Malayan and Singapore special branches collaborated on an arrest list of major opposition members, though doubts arose if Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan could be classified as 'communists'.[166] Up until the end of November 1962, the British declined to support the operation without a pretext, noting that Lim and the Barisan Sosialis had not broken any laws.[167]

The Brunei revolt on 8 December led by A. M. Azahari provided a "heaven-sent opportunity" to take action, as Lim had met Azahari on 3 December.[168] The Malayan government convened the ISC to discuss the operation, while Singapore's Special Branch produced alleged evidence of the communist control of Barisan.[168] On 13 December, Lord Selkirk gave his authorisation for the arrests to proceed on 16 December. However, Lee's attempt to add two Malayan parliamentarians opposed to the formation of Malaysia into the arrest list caused the Malayan representative to rescind his consent, stopping the operation.[168] Tunku suspected that Lee was trying to eliminate his entire opposition, while Lee felt that Tunku was evading his shared responsibility for the arrests.[163]

An ISC meeting was scheduled to be held on 1 February 1963 to remount the operation.[169] During the interim period, Lee had added three names from the United People's Party, one of them being former PAP minister Ong Eng Guan.[169] Selkirk expressed concerns that Ong's arrest lacked any justification and Lee conceded that it was meant as a "warning" to Ong.[169] Tunku told Geofroy Tory, the British High Commissioner in Kuala Lumpur on 30 January, that 'if this operation failed, merger with Singapore was off'.[169] Selkirk was pressured to put his reservations aside and finally consented.[169] On 2 February, Operation Coldstore commenced across Singapore, with 113 detained including Lim and 23 others from Barisan Sosialis.[170][171] Lee offered Lim a path into exile which Lim rejected.[172] The Malayans and British later pressured Lee to retract his comment when he said he "disapproved" of the operation.[170]

In his memoirs, Lee portrayed himself as reluctant in supporting the operation, though declassified British documents revealed that Lee was "somewhat more enthusiastic" than he eventually admitted.[173]

Prime Minister, Singapore in Malaysia (1963–1965)[]

Elections and tensions[]

On 31 August 1963, Lee declared Singapore's independence in a ceremony at the Padang and pledged loyalty to the federal government.[174] With the conclusion of the trials of Barsian Sosialis' leaders, Lee dissolved the legislative assembly on 3 September and called for a snap election.[175][176] He touted "independence through merger" as a success and utilised television and the mass media effectively.[177] In conjunction with Sabah (formerly North Borneo) and Sarawak, Lee proclaimed Singapore as part of Malaysia in a second ceremony on 16 September accompanied by a military parade.[178][i] Lim Chin Siong's arrest had however generated widespread sympathy for the Barisan and a close result was predicted. Australian and British officials expected a Barisan win.[179] When the PAP defeated the Barisan in a landslide victory on 21 September, it was seen as a public endorsement of merger and Lee's social-economical policies.[177][180]

Relations between the PAP and Malaysia's ruling Alliance Party quickly deteriorated as Lee began espousing his policies to the rest of the country. The United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) was also shocked by the loss of three Malay-majority seats to the PAP in the recent 1963 Singapore election.[181] Ultra-nationalists within UMNO alleged that Lee sought to overthrow the Malay monarchies and infringe on rural life.[181] Lee's attempts to reconcile the PAP with UMNO were rebuffed as the latter remained committed to the Malaysian Chinese Association.[181] Further hostility ensued when the PAP decided to contest in the 1964 Malaysian general election in contravention of a gentlemen's agreement that it would disavow itself from peninsula politics.[182] Lee's speeches in Malaysia attracted large crowds and he expected the PAP to win at least seven parliamentary seats.[183] The party ultimately won only one seat in Bungsar, Selangor under Devan Nair.[182] Lee and other party insiders later conceded that UMNO's portrayal of the PAP as a "Chinese party" and its lack of grassroots in the peninsula had undermined its support from the Malay majority.[182][184]

Ethnic tensions had risen prior to the April election when UMNO secretary-general Syed Jaafar Albar utilised the Utusan Melayu to accuse Lee of evicting Malays from their homes in March 1964.[185] Lee explained personally to the affected neighbourhoods that the scheme was part of an urban renewal plan and that eviction notices had been sent to everyone irrespective of race.[186] Albar responded by warning Lee to not "treat the sons of the soil as step-children" and led calls for the deaths of Lee and Social Affairs Minister Othman bin Wok on 12 July.[186] On 21 July, the 1964 race riots in Singapore erupted during a celebration of Prophet Muhammad's birthday, lasting four days, killing 22 and injuring 461.[187] Further riots occurred in late-August and early-September resulting in communities self-segregating from each other, which Lee characterized as "terribly disheartening" and against "everything we had believed in and worked for".[185] Lee never forgot the Malay PAP leaders who stood against UMNO during the turmoil and as late as 1998, paid tribute to them for Singapore's survival.[188]

Malaysian Malaysia and separation[]

Lee's perceptions that merger was becoming infeasible was also due to the federal government's obstruction of his industrialisation program and its imposition of new taxes on Singapore in November 1964.[186] He authorised Goh Keng Swee to renegotiate with Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Razak Hussein on Singapore's place in the federation in early 1965.[186] Seeking to provide an alternative to the Alliance Party government, Lee and his colleagues formed the Malaysian Solidarity Convention (MSC) with the Malayan and Sarawakian opposition on 9 May, with its goals for a Malaysian Malaysia and race-blind society.[186][189] The MSC was seen by UMNO as a threat to the Malay monopoly of power and special rights granted to Malays under Article 153.[190][191] UMNO supreme council member and future prime minister Mahathir Mohamad called the PAP "pro-Chinese, communist-oriented and positively anti-Malay", while others called for Lee's arrest under the Internal Security Act for trying to split the federation.[190][192]

On 26 May, Lee addressed the Malaysian parliament for the final time, delivering his speech entirely in the Malay language. He challenged the Alliance Party to commit itself to a Malaysian Malaysia and denounce its extremists, and also argued that the PAP could better uplift the livelihood of the Malays.[190] Then-social affairs minister Othman Wok later recounted: "I noticed that while he was speaking, the Alliance leaders sitting in front of us, they sank lower and lower because they were embarrassed this man (Lee) could speak Malay better than them".[193] Then-national development minister Lim Kim San also noted: "That was the turning point. They perceived [Lee] as a dangerous man who could one day be the prime minister of Malaya. This was the speech that changed history."[193] Prime Minister Tunku labelled the speech as the final straw which contributed to his decision on 29 June that Singapore's secession was necessary.[194]

Lee summoned Law Minister Edmund W. Barker to draft documents effecting Singapore's separation from the federation and its proclamation of independence. In order to ensure that a 1962 agreement to draw water from Johor was retained, Lee insisted that it be enshrined in the separation agreement and Malaysian constitution.[195] The negotiations of post-separation relations were held in utmost secrecy and Lee tried to prevent secession until he was persuaded to finally relent by Goh on 7 August.[190][196] That day, Lee and several cabinet ministers signed the separation agreement at Razak's home, which stipulated continued co-operation in trade and mutual defence.[197] He returned to Singapore the following day and convened the rest of his cabinet to sign the document, upon which it was flown back to Kuala Lumpur.[196][198]

On 9 August 1965 at 10am, Tunku convened the Malaysian parliament and moved the Constitution of Malaysia (Singapore Amendment) Bill 1965, which passed unanimously by a vote of 126–0 with no PAP representatives present.[199] Singapore’s independence was announced locally via radio at the same time and Lee broke the news to senior diplomats and civil servants.[198][200] In a televised press conference that day, Lee fought back tears and briefly stopped to regain his composure as he formally announced the news to an anxious population:[201]

Every time we look back on this moment when we signed this agreement which severed Singapore from Malaysia, it will be a moment of anguish. For me it is a moment of anguish because all my life. ... You see, the whole of my adult life [...] I have believed in Malaysian merger and the unity of these two territories. You know, it's a people connected by geography, economics, and ties of kinship.[202]

Prime Minister, Republic of Singapore (1965–1990)[]

Despite the momentous event, Lee did not call for the parliament to convene to reconcile issues that Singapore would face immediately as a new nation. Without giving further instructions on who should act in his absence, he went into isolation for six weeks, unreachable by phone, on an isolated chalet. According to then-deputy prime minister Toh Chin Chye, the parliament hung in "suspended animation" until the sitting in December that year.[203]

In his memoirs, Lee said that he was unable to sleep. Upon learning of Lee's condition from the British High Commissioner to Singapore, John Robb, the British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, expressed concern, in response to which Lee replied:

Do not worry about Singapore. My colleagues and I are sane, rational people even in our moments of anguish. We will weigh all possible consequences before we make any move on the political chessboard.[204]

Lee began to seek international recognition of Singapore's independence. Singapore joined the United Nations on 21 September 1965, and founded the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on 8 August 1967 with four other South-East Asian countries. Lee made his first official visit to Indonesia on 25 May 1973, just a few years after the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation under Sukarno's regime. Relations between Singapore and Indonesia substantially improved as subsequent visits were made between the two countries.

Singapore has never had a dominant culture to which immigrants could assimilate even though Malay was the dominant language at that time.[205] Together with efforts from the government and ruling party, Lee tried to create a unique Singaporean identity in the 1970s and 1980s—one which heavily recognised racial consciousness within the umbrella of multiculturalism.

Lee and his government stressed the importance of maintaining religious tolerance and racial harmony, and they were ready to use the law to counter any threat that might incite ethnic and religious violence. For example, Lee warned against "insensitive evangelisation", by which he referred to instances of Christian proselytising directed at Malays. In 1974 the government advised the Bible Society of Singapore to stop publishing religious material in Malay.[206]

Defence[]

The vulnerability of Singapore was deeply felt, with threats from multiple sources including the communists and Indonesia with its confrontational stance. Adding to this vulnerability was the impending withdrawal of British forces from East of Suez. As Singapore gained admission to the United Nations, Lee quickly sought international recognition of Singapore's independence. He appointed Goh Keng Swee as Minister for the Interior and Defence to build up the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) and requested help from other countries, particularly Israel and Taiwan, for advice, training and facilities.[207] In 1967, Lee introduced conscription for all able-bodied male Singaporean citizens age 18 to serve National Service (NS) either in the SAF, Singapore Police Force or the Singapore Civil Defence Force. By 1971, Singapore had 17 national service battalions (16,000 men) with 14 battalions (11,000 men) in the reserves.[208] In 1975, Lee and Republic of China premier Chiang Ching-kuo signed an agreement permitting Singaporean troops to train in Taiwan, under the codename "Project Starlight".[209]

Economy[]

One of Lee's most urgent tasks upon Singapore's independence was to address high unemployment. Together with his economic aide, Economic Development Board chairman Hon Sui Sen, and in consultation with Dutch economist Albert Winsemius, Lee set up factories and initially focused on the manufacturing industry. Before the British completely withdrew from Singapore in 1971, Lee also persuaded the British not to destroy their dock and had the British naval dockyard later converted for civilian use.

Eventually, Lee and his cabinet decided the best way to boost Singapore's economy was to attract foreign investments from multinational corporations (MNCs). By establishing First World infrastructure and standards in Singapore, the new nation could attract American, Japanese and European entrepreneurs and professionals to set up base there. By the 1970s, the arrival of MNCs like Texas Instruments, Hewlett-Packard and General Electric laid the foundations, turning Singapore into a major electronics exporter the following decade.[210] Workers were frequently retrained to familiarise themselves with the work systems and cultures of foreign companies. The government also started several new industries, such as steel mills under 'National Iron and Steel Mills', service industries like Neptune Orient Lines, and the Singapore Airlines.[211]

Lee and his cabinet also worked to establish Singapore as an international financial centre. Foreign bankers were assured of the reliability of Singapore's social conditions, with top-class infrastructure and skilled professionals, and investors were made to understand that the Singapore government would pursue sound macroeconomic policies, with budget surpluses, leading to a stable valued Singapore dollar.[212]

Throughout the tenure of his office, Lee placed great importance on developing the economy, and his attention to detail on this aspect went even to the extent of connecting it with other facets of Singapore, including the country's extensive and meticulous tending of its international image of being a "Garden City",[213] something that has been sustained to this day.

Anti-corruption measures[]

Lee introduced legislation giving the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) greater power to conduct arrests, search, call up witnesses, and investigate bank accounts and income-tax returns of suspected persons and their families.[214] Lee believed that ministers should be well paid in order to maintain a clean and honest government. On 21 November 1986, Lee received a complaint of corruption against then Minister for National Development Teh Cheang Wan.[215] Lee was against corruption and he authorised the CPIB to carry out investigations on Teh, but Teh committed suicide before any charges could be pressed against him.[216] In 1994, he proposed to link the salaries of ministers, judges, and top civil servants to the salaries of top professionals in the private sector, arguing that this would help recruit and retain talent to serve in the public sector.[217]

Population policies[]

In the late 1960s, fearing that Singapore's growing population might overburden the developing economy, Lee started a "Stop at Two" family planning campaign. Couples were urged to undergo sterilisation after their second child. Third or fourth children were given lower priorities in education and such families received fewer economic rebates.[217]

In 1983, Lee sparked the "Great Marriage Debate" when he encouraged Singapore men to choose highly educated women as wives.[218] He was concerned that a large number of graduate women were unmarried.[219] Some sections of the population, including graduate women, were upset by his views.[219] Nevertheless, a match-making agency, the Social Development Unit (SDU),[220] was set up to promote socialising among men and women graduates.[217] In the Graduate Mothers Scheme, Lee also introduced incentives such as tax rebates, schooling, and housing priorities for graduate mothers who had three or four children, in a reversal of the over-successful "Stop at Two" family planning campaign in the 1960s and 1970s.

Lee suggested that perhaps the campaign for women's rights had been too successful:

Equal employment opportunities, yes, but we shouldn't get our women into jobs where they cannot, at the same time, be mothers...our most valuable asset is in the ability of our people, yet we are frittering away this asset through the unintended consequences of changes in our education policy and equal career opportunities for women. This has affected their traditional role ... as mothers, the creators and protectors of the next generation.

— Lee Kuan Yew, "Talent for the future", 14 August 1983[221]

The uproar over the proposal led to a swing of 12.9 percent against the PAP government in the 1984 general election. In 1985, some especially controversial portions of the policy, that gave education and housing priorities to educated women, were abandoned or modified.[222][217]

By the late 1990s the birth rate had fallen so low that Lee's successor Goh Chok Tong extended these incentives to all married women, and gave even more incentives, such as the "baby bonus" scheme.[217]

Water resources[]

Singapore has traditionally relied on water from Malaysia. However, this reliance has made Singapore subject to the possibility of price increases and allowed Malaysian officials to use the water reliance as political leverage by threatening to cut off supply. To reduce this problem, Lee decided to experiment with water recycling in 1974.[223]

Foreign policy[]

Malaysia and Mahathir Mohamad[]

Lee looked forward to improving relationships with Mahathir Mohamad upon the latter's promotion to Deputy Prime Minister. Knowing that Mahathir was in line to become the next Prime Minister of Malaysia, Lee invited Mahathir (through Singapore President Devan Nair) to visit Singapore in 1978. The first and subsequent visits improved both personal and diplomatic relationships between them. Then UMNO's Secretary-General Mahathir asked Lee to cut off all links with the Democratic Action Party; in exchange, Mahathir undertook not to interfere in the affairs of Malay Singaporeans.[citation needed]

In June 1988, Lee and Mahathir reached an agreement in Kuala Lumpur to build the Linggui dam on the Johor River.[224] Lee said he had made more progress solving bilateral issues with Dr Mahathir from 1981 to 1990 than in the previous 12 years with the latter's two predecessors, Tun Abdul Razak and Tun Hussein Onn.[192] Mahathir ordered the lifting of the ban on the export of construction materials to Singapore in 1981, agreed to sort out Malaysia’s claim to Pedra Branca island and affirmed it would honour the 1962 Water Agreement.[192]

One day before Lee left office in November 1990, Malaysia and Singapore signed the Malaysia–Singapore Points of Agreement of 1990 (POA). Malayan Railways (KTM) would vacate the Tanjong Pagar railway station and move to Bukit Timah while all KTM's land between Bukit Timah and Tanjong Pagar would revert to Singapore. Railway land at Tanjong Pagar would be handed over to a private limited company for joint development, the equity of which would be divided 60% to Malaysia and 40% to Singapore. However, Prime Minister Mahathir expressed his displeasure with the POA, for it failed to include a piece of railway land in Bukit Timah for joint development in 1993. Not until 2010 was the matter resolved, under Malaysia's Najib Razak and Lee's son, Lee Hsien Loong.

Following Lee's death, Mahathir posted a blog post that suggested his respect for Lee despite their differences, stating that while "I am afraid on most other issues we could not agree [...] [h]is passage marks the end of the period when those who fought for independence lead their countries and knew the value of independence. ASEAN lost a strong leadership after President Suharto and Lee Kuan Yew".[225]

United States[]

Lee fully supported the USA in the Vietnam War. Even as the war began to lose its popularity in the United States, Lee made his first official visit to the United States in October 1967, and declared to President Lyndon B. Johnson that his support for the war in Vietnam was "unequivocal". Lee saw the war as necessary for states in Southeast Asia like Singapore to buy time for stabilizing their governments and economies.[226][227] Lee cultivated close relationships with presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan,[228] as well as former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger[229] and George Shultz.[230] In 1967 Nixon, who was running for president in 1968, visited Singapore and met with Lee, who advised that the United States had much to gain by engaging with China, culminating in Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to China.[231]

In October 1985, Lee made a state visit to the United States on the invitation of President Reagan and addressed a joint session of the United States Congress. Lee stressed to Congress the importance of free trade and urged it not to turn towards protectionism.

It is inherent in America's position as the preeminent economic, political and military power to have to settle and uphold the rules for orderly change and progress... In the interests of peace and security America must uphold the rules of international conduct which rewards peaceful cooperative behaviour and punishes transgressions of the peace. A replay of the depression of the 1930s, which led to World War II, will be ruinous for all. All the major powers of the West share the responsibility of not repeating this mistake. But America's is the primary responsibility, for she is the anchor economy of the free- market economies of the world.[228]

In May 1988, E. Mason "Hank" Hendrickson was serving as the First Secretary of the United States Embassy when he was expelled by the Singapore government.[232][233][234] The Singapore government alleged that Hendrickson attempted to interfere in Singapore's internal affairs by cultivating opposition figures in a "Marxist conspiracy".[235] Then-First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong claimed that Hendrickson's alleged conspiracy could have resulted in the election of 20 or 30 opposition politicians to Parliament, which in his words could lead to "horrendous" effects, possibly even the paralysis and fall of the Singapore government.[236] In the aftermath of Hendrickson's expulsion, the U.S. State Department praised Hendrickson's performance in Singapore and denied any impropriety in his actions.[232] The State Department also expelled Robert Chua, a senior-level Singaporean diplomat equal in rank to Hendrickson, from Washington, D.C. in response.[237][238] The State Department's refusal to reprimand Hendrickson, along with its expulsion of the Singaporean diplomat, sparked a rare protest in Singapore by the National Trades Union Congress; they drove buses around the U.S. embassy, held a rally attended by four thousand workers, and issued a statement deriding the U.S. as "sneaky, arrogant, and untrustworthy".[239]

China[]

Singapore did not establish diplomatic relations with China until the USA and Southeast Asian had decided they wanted to do so in order to avoid portraying a pro-China bias.[240][241] His official visits to China starting in 1976 were conducted in English, to assure other countries that he represented Singapore, and not a "Third China" (the first two being the Republic of China and People's Republic of China).[242]

In November 1978, after China had stabilized following political turmoil in the aftermath of Mao Zedong's death and the Gang of Four, Deng Xiaoping visited Singapore and met Lee. Deng, who was very impressed with Singapore's economic development, greenery and housing, and later sent tens of thousands of Chinese to Singapore and countries around the world to learn from their experiences and bring back their knowledge as part of the opening of China beginning in December 1978. Lee, on the other hand, advised Deng to stop exporting Communist ideologies to Southeast Asia, advice that Deng later followed.[243][244] This culminated in the exchange of Trade Offices between the two nations in September 1981.[245] In 1985, commercial air services between mainland China and Singapore commenced[246] and China appointed Goh Keng Swee, Singapore's finance minister in the post-independence years, as advisor on the development of Special Economic Zones.[247]

On 3 October 1990, Singapore revised diplomatic relations from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China.

Cambodia[]

Lee opposed the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1978.[248] The Singapore government organised an international campaign to condemn Vietnam and provided aid to the Khmer Rouge which was fighting against Vietnamese occupation during the Cambodian–Vietnamese War from 1978 to 1989. In his memoirs, Lee recounted that in 1982, "Singapore gave the first few hundreds of several batches of AK-47 rifles, hand grenades, ammunition and communication equipment" to the Khmer Rouge resistance forces.[249][250]

Senior Minister (1990–2004)[]

After leading the PAP to victory in seven elections, Lee stepped down on 28 November 1990, handing over the prime ministership to Goh Chok Tong.[251] By that time he had become the world's longest-serving prime minister.[252] This was the first leadership transition since independence. Goh was elected as the new Prime Minister by the younger ministers then in office.

When Goh Chok Tong became head of government, Lee remained in the cabinet with a non-executive position of Senior Minister[253] and played a role he described as advisory. In public, Lee would refer to Goh as "my Prime Minister", in deference to Goh's authority.[citation needed]

Lee subsequently stepped down as Secretary-General of the PAP and was succeeded by Goh Chok Tong on 2 December 1992.[254]

Minister Mentor (2004–2011)[]

From the decade of the 2000s, Lee expressed concern about the declining proficiency of Mandarin among younger Chinese Singaporeans. In one of his parliamentary speeches, he said: "Singaporeans must learn to juggle English and Mandarin". Subsequently, in December 2004, Lee stepped down to become minister mentor and started a year-long campaign called "华语 Cool!" (Mandarin is Cool!) in an attempt to attract young viewers to learn and speak Mandarin.[255]

In June 2005, Lee published a book, Keeping My Mandarin Alive, documenting his decades of effort to master Mandarin, a language that he said he had to re-learn due to disuse:

[B]ecause I don't use it so much, therefore it gets disused and there's language loss. Then I have to revive it. It's a terrible problem because learning it in adult life, it hasn't got the same roots in your memory.

On 13 September 2008, Lee underwent successful treatment for abnormal heart rhythm (atrial flutter) at Singapore General Hospital, but he was still able to address a philanthropy forum via video link from hospital.[256] On 28 September 2010, he was hospitalised for a chest infection, cancelling plans to attend the wake of the Senior Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Balaji Sadasivan.[257]

In November 2010, Lee's private conversations with James Steinberg, US Deputy Secretary of State, on 30 May 2009 were among the US Embassy cables leaked by WikiLeaks. In a US Embassy report classified as "Secret", Lee gave his assessment of a number of Asian leaders and views on political developments in North Asia, including implications for nuclear proliferation.[258]

In January 2011, the Straits Times Press published the book Lee Kuan Yew: Hard Truths To Keep Singapore Going.[259] Targeted at younger Singaporeans, it was based on 16 interviews with Lee by seven local journalists in 2008–2009. The first print run of 45,000 copies sold out in less than a month after it was launched in January 2011. Another batch of 55,000 copies was made available shortly after.[260]

After the 2011 general elections in which the Workers' Party, a major opposition political party in Singapore, made unprecedented gains by winning a Group Representation Constituency (GRC), Lee announced that he decided to leave the Cabinet for the Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong, and his team to have a clean slate.[261] Analysts such as Citigroup economist Kit Wei Zheng believed that the senior Lee had contributed to the PAP's poor performance.[262] In particular, he stated during the election campaign that the voters of Aljunied constituency had "five years to live and repent" if they voted for the Workers' Party, which was said to have backfired for the PAP as the opposition went on to win Aljunied.[263]

In a column in the Sunday Times on 6 November 2011, Lee's daughter, Lee Wei Ling, revealed that her father suffered from peripheral neuropathy.[264] In the column, she recounted how she first noticed her father's ailments when she accompanied him to meet the former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Connecticut in October 2009. Wei Ling, a neurologist, "did a few simple neurological tests and decided the nerves to his legs were not working as they should". A day later, when interviewed at a constituency tree-planting event, Lee stated: "I have no doubt at all that this has not affected my mind, my will nor my resolve" and that "people in wheel chairs can make a contribution. I've still got two legs, I will make a contribution".[265]

Illness and death[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

On 15 February 2013, Lee was admitted to Singapore General Hospital after suffering a prolonged cardiac dysrhythmia which was followed by a brief stoppage of blood flow to the brain.[266][267][268][269] For the first time in his career as a politician, Lee missed the annual Chinese New Year dinner at his Tanjong Pagar Constituency, where he was supposed to be the guest-of-honour.[270][271] He was subsequently discharged, but continued to receive anti-coagulant therapy.[272][273][274]

The following year, Lee missed his constituency's Chinese New Year dinner for the second consecutive time owing to bodily bacterial invasion.[275] In April 2014, a photo depicting a cadaverous Lee was released online, drawing strong reactions from netizens.[276]

On 5 February 2015, suffering from pneumonia, Lee was hospitalised and was put on a ventilator at the intensive care unit of Singapore General Hospital, although his condition was reported initially as "stable".[277][278] A 26 February update stated that he was again being given antibiotics, while being sedated and still under mechanical ventilation.[279][280] From 17 to 22 March, Lee continued weakening as he suffered an infection while on life support, and he was described as "critically ill".[281][282][283]

On 18 March that year, a death hoax website reported false news of Lee's death. The suspect is an unidentified minor who created a false webpage that resembled the PMO official website.[284] Several international news organisations reported on Lee's death based on this and later retracted their statements.[285][286]

On 23rd of that same month, Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced his father's death at the age of 91.[287] Lee had died at 03:18 Singapore Standard Time (UTC+08:00).[288][287] A week of national mourning took place,[289] during which time Lee was lying in state at Parliament house. During this time, 1.7 million Singaporean residents as well as world leaders paid tribute to him at Parliament house and community tribute sites throughout the country.[290][291][2] A state funeral for Lee was held on 29th of that same month and attended by world leaders.[292] Later that day, Lee was cremated in a private ceremony at the Mandai Crematorium.[293]

Legacy[]

I'm not saying that everything I did was right, but everything I did was for an honourable purpose. I had to do some nasty things, locking fellows up without trial.

Lee in 2010, reflecting on his legacy[294]

As Singapore's Prime Minister from 1959 to 1990, Lee presided over many of Singapore's advancements. Singapore's Gross National Product per capita rose from $1,240 in 1959 to $18,437 in 1990. The unemployment rate in Singapore dropped from 13.5% in 1959 to 1.7% in 1990. External trade increased from $7.3 billion in 1959 to $205 billion in 1990. In other areas, the life expectancy at birth for Singaporeans rose from 65 years at 1960 to 74 years in 1990. The population of Singapore increased from 1.6 million in 1959 to 3 million in 1990. The number of public flats in Singapore rose from 22,975 in 1959 (then under the Singapore Improvement Trust) to 667,575 in 1990. The Singaporean literacy rate increased from 52% in 1957 to 90% in 1990. Telephone lines per 100 Singaporeans increased from 3 in 1960 to 38 in 1990. Visitor arrivals to Singapore rose from 100,000 in 1960 to 5.3 million in 1990.[295]

During the three decades in which Lee held office, Singapore grew from a developing country to one of the most developed nations in Asia.[296] Lee said that Singapore's only natural resources are its people and their strong work ethic.[297]

Lee's achievements in Singapore had a profound effect on the Communist leadership in China, who made a major effort, especially under Deng Xiaoping, to emulate his policies of economic growth, entrepreneurship and subtle suppression of dissent. Over 22,000 Chinese officials were sent to Singapore to study its methods.[298] He has also had a major influence on thinking in Russia in recent years.[299][298]

Other world leaders also praised Lee. Henry Kissinger once wrote of Lee: "One of the asymmetries of history is the lack of correspondence between the abilities of some leaders and the power of their countries." Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher praised "his way of penetrating the fog of propaganda and expressing with unique clarity the issues of our time and the way to tackle them".[300]

On the other hand, many Singaporeans and Westerners have criticised Lee as authoritarian and as intolerant of dissent, citing his numerous attempts to sue political opponents and newspapers who express unfavourable opinions of Lee. Reporters Without Borders, an international media pressure group, requested Lee and other senior Singaporean officials to stop taking libel suits against journalists.[301]

In addition, Lee was accused of promoting a culture of elitism among Singapore's ruling class. Michael Barr in his book The Ruling Elite of Singapore: Networks of Influence and Power claims that the system of meritocracy in Singapore is not quite how the government presents it; rather, it is a system of nepotism and collusion run by Lee's family and their crony friends and allies. Barr claims further that although the government presents the city-state as multi-ethnic and cosmopolitan, all the networks are dominated by ethnic Chinese, leaving the minority Malay and Indian ethnic groups powerless. According to Barr, the entire process of selecting and grooming of future political and economic talent is monopolised in the hands of the ruling People's Action Party, which Lee himself founded with a handful of other British-educated ethnic Chinese that he met in his days at Cambridge.[302]

Legal suits[]

Action against Far Eastern Economic Review[]

In April 1977, just months after a general election which saw the People's Action Party winning all 69 seats, the Internal Security Department, under orders from Lee, detained Ho Kwon Ping, the Singapore correspondent of the Far Eastern Economic Review, as well as his predecessor Arun Senkuttavan, over their reporting. Ho was detained under the Internal Security Act which allows for indefinite trial, held in solitary confinement for two months, and charged with endangering national security. Following a televised confession in which Ho confessed to "pro-communist activities",[303] he was fined $3,000. Lee Kuan Yew later charged FEER editor, Derek Davies, of participating in "a diabolical international Communist plot" to poison relations between Singapore and neighbouring Malaysia.

In 1987 Lee restricted sale of the Review in Singapore after it published an article about the detention of Roman Catholic church workers, reducing circulation of the magazine from 9,000 to 500 copies,[304] on the grounds that it was "interfering in the domestic politics of Singapore."[305]

On 24 September 2008 the High Court of Singapore, in a summary judgment by Justice Woo Bih Li, ruled that the Far Eastern Economic Review magazine (Hugo Restall, editor), defamed Lee and his son, the Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong. The court found the 2006 article "Singapore's 'Martyr': Chee Soon Juan" suggested that Lee "ha[d] been running and continue[d] to run Singapore in the same corrupt manner as Durai operated [the National Kidney Foundation] and he ha[d] been using libel actions to suppress those who would question [him] to avoid exposure of his corruption".[306] The court ordered the Review, owned by Dow Jones & Company (in turn owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corp), to pay damages to the complainants. The magazine appealed but lost.[306][307]