Moggaliputta-Tissa

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Moggaliputtatissa (ca. 327–247 BCE), was a Buddhist monk and scholar who was born in Pataliputra, Magadha (now Patna, India) and lived in the 3rd century BCE. He is associated with the Third Buddhist council, the emperor Ashoka and the Buddhist missionary activities which took place during his reign.[1]

Moggaliputtatissa is seen by the Theravada Buddhist tradition as the founder of "Vibhajjavāda", the tradition of which Theravada is a part as well as the author of the Kathāvatthu.[2][3] He is seen as the defender of the true teaching or Dhamma against corruption, during a time where many kinds of wrong view had arisen and as the force behind the Ashokan era Buddhist missionary efforts.[4][5]

The Sri Lankan Buddhist philosopher David Kalupahana sees him as a predecessor of Nagarjuna in being a champion of the Middle Way and a reviver of the original philosophical ideals of the Buddha.[6]

Overview[]

Evidence from various Buddhist sources show that Moggaliputtatissa seems to have been an influential figure who lived during the time of emperor Ashoka. He is associated with the Third Buddhist councils and with the missionary work which led to the spread of Buddhism during the reign of Ashoka.[5] He also seems to have been a staunch critic of certain Buddhist doctrinal views, mainly Sarvāstivāda (an eternalist theory of time), Pudgalavāda ("personalism") and Lokottaravāda ("transcendentalism").[7] Because of this, he is seen as one of the founders and defenders of the Theravada, which to this day rejects these three doctrines as unorthodox deviations from the original teaching of the Buddha Dhamma. Theravada sources state that with the aid of Moggaliputtatissa, Ashoka was able to purge the Buddhist Sangha of numerous heretics.[8]

Theravada sources, especially the Kathāvatthu, also explain these Buddhist doctrinal debates in detail. Bhante Sujato also notes how the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma text called the Vijñānakāya contains a section titled the "Moggallāna section" which contains arguments against the theory of "all exists" from "Samaṇa Moggallāna".[9] The Śāripūtraparipṛcchā, a text of the Mahāsaṅghikas, also mentions a figure by the name of "Moggallāna" or "Moggalla-upadesha" (Chinese: 目揵羅優婆提舍) as the founder of "the Dharmaguptaka school, the Suvarṣaka school, and the Sthavira school."[10] According to Sujato, it is likely that this is a variant rendering of Moggaliputtatissa.[11]

According to Johannes Bronkhorst however, the current historical evidence shows that the main issues discussed at the Third Council of Pataliputra, which led to the expulsion of monks from the sangha were actually issues of Vinaya (monastic discipline), not doctrine.[12]

Authorship of the Kathāvatthu[]

Certain Theravada sources state that Moggaliputtatissa compiled the Kathāvatthu, a work which outlines numerous doctrinal issues and views and lays out the orthodox Theravada positions.

Bhante Sujato, in his study of the Buddhist sectarian literature, notes how the passages depicting the Third council in the Sudassanavinayavibhāsā does not mention the compilation of the Kathāvatthu by Moggaliputtatissa, but that later works such as the Samantapāsādikā and Kathāvatthu-aṭṭhakathā add this attribution. He concludes that the attribution of the Kathāvatthu to Moggaliputtatissa "are interpolations at a late date in the Mahāvihāra, presumably made by Buddhaghosa."[13] According to Sujato, this work could not have been composed at the time of the third council "for it is the outcome of a long period of elaboration, and discusses many views of schools that did not emerge until long after the time of Aśoka." Nevertheless:

...there is no reason why the core of the book should not have been started in Aśoka’s time, and indeed K. R. Norman has shown that particularly the early chapters have a fair number of Magadhin grammatical forms, which are suggestive of an Aśokan provenance. In addition, the place names mentioned in the text are consistent with such an early dating. So it is possible that the main arguments on the important doctrinal issues, which tend to be at the start of the book, were developed by Moggaliputtatissa and the work was elaborated later.[9]

Upagupta[]

According to John S. Strong, numerous parallels between the stories told about Upagupta in the northern tradition and Moggaliputtatissa in the southern tradition have led various scholars such as L.A. Waddell and Alex Wayman to conclude that they are the same person.[14] Rupert Gethin writes:

As has long been recognised, there are striking parallels in the stories of Moggaliputta Tissa and Upagupta. Both are closely associated with Asoka as important monks in his capital, yet Pali sources know of no Upagupta just as northern sources know of no Moggaliputta Tissa. Is it plausible that two monks of such importance and eminence should be completely forgotten by the other tradition? Of course, one possibility is that Moggaliputta Tissa and Upagupta are one and the same. Yet this makes little sense of the narrative differences. While Upagupta shares with Moggaliputta Tissa a narrative association with Aśoka, Upagupta does not help Aśoka expel non-Buddhist ascetics from the Saṅgha, he does not preside over a third council, and he does not recite the Kathāvatthu. Rather than seeing the story of Upagupta as somehow corroborative evidence that Moggaliputta Tissa was associated with Asoka in the manner described in the Samantapāsādikā, it seems more reasonable to see the details of the stories that associate figures such as Moggaliputta Tissa, Upagupta and Mahinda with Asoka as part of a more general strategy to enhance the reputation and prestige of these teachers and their lineages.[5]

Influence[]

In Theravada Buddhism, Moggaliputtatissa is seen as a heroic figure of the Ashokan era, who purified the Sangha of non-Buddhists and heretical views as well as the leader of the Sangha during the spread of Buddhism throughout South Asia, most importantly to Sri Lanka.[5]

The Sri Lankan Buddhist philosopher David Kalupahana saw Moggaliputtatissa's main philosophical contribution as the "elimination of absolutist and essentialist or reductionist perspectives" which were incompatible with the original Buddhist philosophy.[15][16] He also saw Moggaliputtatissa as a precursor to Nagarjuna, in that both were successful in defending the middle way approach which avoids both eternalism and nihilism and both defended the doctrine of the insubstantiality of dharmas (dharma nairātmya).[17]

Theravāda account[]

According to Sri Lankan Theravada sources, Moggaliputtatissa was an arhat and a revered elder (thera) of the Buddhist sangha in Pataliputra, as well as the teacher of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, and is said to have presided over the Third Buddhist Council. His story is discussed in sources such as the Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle", abbrev. Mhv) and the Vinaya commentary called Samantapāsādikā.[5]

He was the son of Mogalli of Pataliputra, as Tissa. According to the Mahavamsa, Tissa, who was thoroughly proficient, at a young age was sought after by the Buddhist monks Siggava and Candavajji for conversion, as they went on their daily alms round. At the age of seven, Tissa was angered when Siggava, a Buddhist monk, occupied his seat in his house and berated him. Siggava responded by asking Tissa a question about the Cittayamaka which Tissa was not able to answer, and he expressed a desire to learn the dharma, converting to Buddhism. After obtaining the consent of his parents, he joined the Sangha as Siggava's disciple, who taught him the Vinaya and Candavajji who taught him Abhidhamma. He later attained arahantship and became an acknowledged leader of the monks at Pataliputra (Mhv.v.95ff, 131ff.).

At a festival for the dedication of the Great Pataliputra monastery called the as well as the other viharas built by Ashoka, Moggaliputta-Tissa, in answer to a question, informed Ashoka that one becomes a kinsman of the Buddha's religion only by letting one's son or daughter enter the Sangha. Upon this suggestion, Ashoka had both his son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta ordained (Mhv.v.191ff.).

According to the Samantapāsādikā, due to the great wealth which accrued to the sangha through Ashoka's patronage, many non-buddhist ascetics (titthiyas) joined the order or began to dress and act like Buddhists. Because of this, the formal acts of the sangha (sanghakamma) were compromised and monks did not feel they were able to carry out the uposatha ceremony which was thus suspended for a period of seven years at the Aśokārāma.[5] Moggaliputtatissa thus left the monks of Pataliputra under the leadership of Mahinda, and lived in self-imposed solitary retreat on the Ahoganga pabbata mountain. After seven years, Ashoka recalled him to Pataliputra after some monks had been murdered by royal officials attempting to force them to hold the uposatha.[5]

The Samantapāsādikā then states that Moggaliputtatissa instructed Ashoka in the Buddha Dhamma for seven days, after which Ashoka summoned all the monks to the Aśokārāma to question them on Buddhist doctrine. Ashoka was able to recognize those who were non-Buddhists and expelled all of them (60,000 monks). After this purification of the sangha, the uposatha ceremony was held and the Third Buddhist Council was convened in the Aśokārāma, presided over by Moggaliputtatissa.[5] Moggaliputtatissa is then said to have compiled the Kathavatthu, in refutation of various wrong views held by the expelled ascetics, and it was in this council that this text was approved and added to the Abhidhamma.

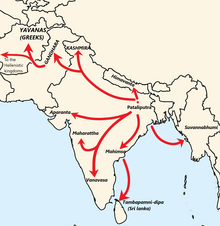

The final part of the Samantapāsādikā's background narrative tells the story of how Moggaliputtatissa organized nine different missions to spread the sasana (the Buddha's dispensation) to the following "border regions" where it would be "firmly established":[5][20]

- Kasmīra and Gandhāra,

- Mahiṃsa

- Vanavāsi (possibly Kanara),

- Aparantaka,

- Mahāraṭṭha,

- Yonakaloka (i.e. "The realm of the Greeks", possibly Bactria),

- Himavanta (Nepal),

- Suvaṇṇabhūmi (Possibly Myanmar),

- Tambapaṇṇidīpa (Sri Lanka)

Moggaliputtatissa died at the age of eighty in the twenty-sixth year of Ashoka's reign and his relics were enshrined in a stupa in Sanchi along with nine other arahants.

References[]

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2007), Sects and Sectarianism: The origins of Buddhist schools, Santipada, p. 13, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2007), Sects and Sectarianism: The origins of Buddhist schools, Santipada, p. 104, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Karl H. Potter, Robert E. Buswell, Abhidharma Buddhism to 150 A.D., Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1970, chapter 8.

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2007), Sects and Sectarianism: The origins of Buddhist schools, Santipada, pp. 27–29, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gethin, Rupert, Was Buddhaghosa a Theravādin? Buddhist Identity in the Pali Commentaries and Chronicles, in "How Theravāda is Theravāda? Exploring Buddhist Identities", ed. by Peter Skilling and others, pp. 1–63, 2012.

- ^ David Kalupahana, Mulamadhyamakakarika of Nagarjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. Motilal Banarsidass, 2005, pages 2,5.

- ^ Kalupahana, David J. (1992) A History of Buddhist Philosophy: Continuities and Discontinuities, University of Hawaii Press, p. 132.

- ^ Sukumar Dutt (1988), Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India: Their History and Their Contribution to Indian Culture, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, pp. 108-110.

- ^ a b Sujato, Bhante (2012), Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools, Santipada, p. 116, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2007), Sects and Sectarianism: The origins of Buddhist schools, Santipada, p. 75, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2007), Sects and Sectarianism: The origins of Buddhist schools, Santipada, pp. 126–127, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes, Kathavatthu and Vijñanakaya, published in: Premier Colloque Étienne Lamotte (Bruxelles et Liège 24-27 septembre 1989). Université Catholique de Louvain: Institut Orientaliste Louvain-la-Neuve. 1993. Pp. 57-61.

- ^ Sujato, Bhante (2012), Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools, Santipada, p. 105, ISBN 9781921842085

- ^ Strong, John S. (2017), The Legend and Cult of Upagupta: Sanskrit Buddhism in North India and Southeast Asia, Princeton University Press, p. 147.

- ^ Kalupahana, David J. (1992) A History of Buddhist Philosophy: Continuities and Discontinuities, University of Hawaii Press, p. 145.

- ^ Kalupahana, David J. (1991), Mūlamadhyamakakārikā of Nāgārjuna, Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 24.

- ^ Kalupahana, David J. (1986) Nagarjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way, SUNY Press, p. 2.

- ^ Khan, Zeeshan (2016). Right to Passage: Travels Through India, Pakistan and Iran. SAGE Publications India. p. 51. ISBN 9789351509615.

- ^ Roy, Kumkum (2009). Historical Dictionary of Ancient India. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 243. ISBN 9780810853669.

- ^ Burgess, James (2013), The Cave Temples of India, Cambridge University Press, p. 17.

- Ahir, Diwan Chand (1989). Heritage of Buddhism.

- Arhats

- 320s BC births

- 247 BC deaths

- Indian Buddhists

- 4th-century BC Buddhist monks

- 3rd-century BC Buddhist monks

- Indian Buddhist monks

- Converts to Buddhism

- People from Patna

- Ancient Indian philosophers

- 4th-century BC Indian monks

- 3rd-century BC Indian monks

- Scholars from Bihar

- Ashoka

- Theravada