Pentagon

| Pentagon | |

|---|---|

An equilateral pentagon, i.e. a pentagon whose five sides all have the same length | |

| Edges and vertices | 5 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | 108° (if equiangular, including regular) |

In geometry, a pentagon (from the Greek πέντε pente and γωνία gonia, meaning five and angle[1]) is any five-sided polygon or 5-gon. The sum of the internal angles in a simple pentagon is 540°.

A pentagon may be simple or self-intersecting. A self-intersecting regular pentagon (or star pentagon) is called a pentagram.

Regular pentagons[]

| Regular pentagon | |

|---|---|

A regular pentagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 5 |

| Schläfli symbol | {5} |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D5), order 2×5 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | 108° |

| Dual polygon | Self |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

A regular pentagon has Schläfli symbol {5} and interior angles of 108°.

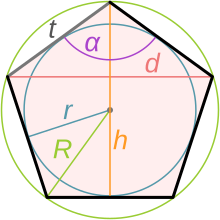

A regular pentagon has five lines of reflectional symmetry, and rotational symmetry of order 5 (through 72°, 144°, 216° and 288°). The diagonals of a convex regular pentagon are in the golden ratio to its sides. Its height (distance from one side to the opposite vertex) and width (distance between two farthest separated points, which equals the diagonal length) are given by

where R is the radius of the circumcircle.

The area of a convex regular pentagon with side length t is given by

A pentagram or pentangle is a regular star pentagon. Its Schläfli symbol is {5/2}. Its sides form the diagonals of a regular convex pentagon – in this arrangement the sides of the two pentagons are in the golden ratio.

When a regular pentagon is circumscribed by a circle with radius R, its edge length t is given by the expression

and its area is

since the area of the circumscribed circle is the regular pentagon fills approximately 0.7568 of its circumscribed circle.

Derivation of the area formula[]

The area of any regular polygon is:

where P is the perimeter of the polygon, and r is the inradius (equivalently the apothem). Substituting the regular pentagon's values for P and r gives the formula

with side length t.

Inradius[]

Similar to every regular convex polygon, the regular convex pentagon has an inscribed circle. The apothem, which is the radius r of the inscribed circle, of a regular pentagon is related to the side length t by

Chords from the circumscribed circle to the vertices[]

Like every regular convex polygon, the regular convex pentagon has a circumscribed circle. For a regular pentagon with successive vertices A, B, C, D, E, if P is any point on the circumcircle between points B and C, then PA + PD = PB + PC + PE.

Point in plane[]

For an arbitrary point in the plane of a regular pentagon with circumradius , whose distances to the centroid of the regular pentagon and its five vertices are and respectively, we have [2]

If are the distances from the vertices of a regular pentagon to any point on its circumcircle, then [2]

Construction of a regular pentagon[]

The regular pentagon is constructible with compass and straightedge, as 5 is a Fermat prime. A variety of methods are known for constructing a regular pentagon. Some are discussed below.

Richmond's method[]

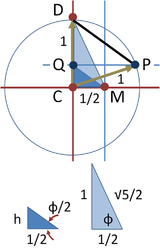

One method to construct a regular pentagon in a given circle is described by Richmond[3] and further discussed in Cromwell's Polyhedra.[4]

The top panel shows the construction used in Richmond's method to create the side of the inscribed pentagon. The circle defining the pentagon has unit radius. Its center is located at point C and a midpoint M is marked halfway along its radius. This point is joined to the periphery vertically above the center at point D. Angle CMD is bisected, and the bisector intersects the vertical axis at point Q. A horizontal line through Q intersects the circle at point P, and chord PD is the required side of the inscribed pentagon.

To determine the length of this side, the two right triangles DCM and QCM are depicted below the circle. Using Pythagoras' theorem and two sides, the hypotenuse of the larger triangle is found as . Side h of the smaller triangle then is found using the half-angle formula:

where cosine and sine of ϕ are known from the larger triangle. The result is:

With this side known, attention turns to the lower diagram to find the side s of the regular pentagon. First, side a of the right-hand triangle is found using Pythagoras' theorem again:

Then s is found using Pythagoras' theorem and the left-hand triangle as:

The side s is therefore:

which is a well-established result.[5]

Carlyle circles[]

The Carlyle circle was invented as a geometric method to find the roots of a quadratic equation.[6] This methodology leads to a procedure for constructing a regular pentagon. The steps are as follows:[7]

- Draw a circle in which to inscribe the pentagon and mark the center point O.

- Draw a horizontal line through the center of the circle. Mark the left intersection with the circle as point B.

- Construct a vertical line through the center. Mark one intersection with the circle as point A.

- Construct the point M as the midpoint of O and B.

- Draw a circle centered at M through the point A. Mark its intersection with the horizontal line (inside the original circle) as the point W and its intersection outside the circle as the point V.

- Draw a circle of radius OA and center W. It intersects the original circle at two of the vertices of the pentagon.

- Draw a circle of radius OA and center V. It intersects the original circle at two of the vertices of the pentagon.

- The fifth vertex is the rightmost intersection of the horizontal line with the original circle.

Steps 6–8 are equivalent to the following version, shown in the animation:

- 6a. Construct point F as the midpoint of O and W.

- 7a. Construct a vertical line through F. It intersects the original circle at two of the vertices of the pentagon. The third vertex is the rightmost intersection of the horizontal line with the original circle.

- 8a. Construct the other two vertices using the compass and the length of the vertex found in step 7a.

Using trigonometry and the Pythagorean Theorem[]

The construction[]

- We first note that a regular pentagon can be divided into 10 congruent triangles as shown in the Observation. Also, cos 36° = .†

- In Step 1, we use four units (shown in blue) and a right angle to construct a segment of length 1+√5, specifically by creating a 1-2-√5 right triangle and then extending the hypotenuse of √5 by a length of 1. We then bisect that segment – and then bisect again – to create a segment of length (shown in red.)

- In Step 2, we construct two concentric circles centered at O with radii of length 1 and length . We then place P arbitrarily on the smaller circle, as shown. Constructing a line perpendicular to OP passing through P, we construct the first side of the pentagon by using the points created at the intersection of the tangent and the unit circle. Copying that length four times along the outer edge of the unit circles gives us our regular pentagon.

† Proof that cos 36° = []

-

- (using the angle addition formula for cosine)

- (using double and half angle formulas)

- Let u = cos 36°. First, note that 0 < u < 1 (which will help us simplify as we work). Now,

This follows quickly from the knowledge that twice the sine of 18 degrees is the reciprocal golden ratio, which we know geometrically from the triangle with angles of 72,72,36 degrees. From trigonometry, we know that the cosine of twice 18 degrees is 1 minus twice the square of the sine of 18 degrees, and this reduces to the desired result with simple quadratic arithmetic.

Side length is given[]

The regular pentagon according to the golden ratio, dividing a line segment by exterior division

- Draw a segment AB whose length is the given side of the pentagon.

- Extend the segment BA from point A about three quarters of the segment BA.

- Draw an arc of a circle, center point B, with the radius AB.

- Draw an arc of a circle, center point A, with the radius AB; there arises the intersection F.

- Construct a perpendicular to the segment AB through the point F; there arises the intersection G.

- Draw a line parallel to the segment FG from the point A to the circular arc about point A; there arises the intersection H.

- Draw an arc of a circle, center point G with the radius GH to the extension of the segment AB; there arises the intersection J.

- Draw an arc of a circle, center point B with the radius BJ to the perpendicular at point G; there arises the intersection D on the perpendicular, and the intersection E with the circular arc that was created about the point A.

- Draw an arc of a circle, center point D, with the radius BA until this circular arc cuts the other circular arc about point B; there arises the intersection C.

- Connect the points BCDEA. This results in the pentagon.

The golden ratio[]

Euclid's method[]

A regular pentagon is constructible using a compass and straightedge, either by inscribing one in a given circle or constructing one on a given edge. This process was described by Euclid in his Elements circa 300 BC.[8][9]

Simply using a protractor (not a classical construction)[]

A direct method using degrees follows:

- Draw a circle and choose a point to be the pentagon's (e.g. top center)

- Choose a point A on the circle that will serve as one vertex of the pentagon. Draw a line through O and A.

- Draw a guideline through it and the circle's center

- Draw lines at 54° (from the guideline) intersecting the pentagon's point

- Where those intersect the circle, draw lines at 18° (from parallels to the guideline)

- Join where they intersect the circle

After forming a regular convex pentagon, if one joins the non-adjacent corners (drawing the diagonals of the pentagon), one obtains a pentagram, with a smaller regular pentagon in the center. Or if one extends the sides until the non-adjacent sides meet, one obtains a larger pentagram. The accuracy of this method depends on the accuracy of the protractor used to measure the angles.

Physical methods[]

- A regular pentagon may be created from just a strip of paper by tying an overhand knot into the strip and carefully flattening the knot by pulling the ends of the paper strip. Folding one of the ends back over the pentagon will reveal a pentagram when backlit.

- Construct a regular hexagon on stiff paper or card. Crease along the three diameters between opposite vertices. Cut from one vertex to the center to make an equilateral triangular flap. Fix this flap underneath its neighbor to make a pentagonal pyramid. The base of the pyramid is a regular pentagon.

Symmetry[]

The regular pentagon has Dih5 symmetry, order 10. Since 5 is a prime number there is one subgroup with dihedral symmetry: Dih1, and 2 cyclic group symmetries: Z5, and Z1.

These 4 symmetries can be seen in 4 distinct symmetries on the pentagon. John Conway labels these by a letter and group order.[10] Full symmetry of the regular form is r10 and no symmetry is labeled a1. The dihedral symmetries are divided depending on whether they pass through vertices (d for diagonal) or edges (p for perpendiculars), and i when reflection lines path through both edges and vertices. Cyclic symmetries in the middle column are labeled as g for their central gyration orders.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g5 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can be seen as directed edges.

Equilateral pentagons[]

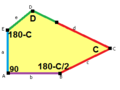

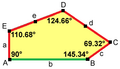

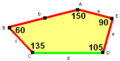

An equilateral pentagon is a polygon with five sides of equal length. However, its five internal angles can take a range of sets of values, thus permitting it to form a family of pentagons. In contrast, the regular pentagon is unique up to similarity, because it is equilateral and it is equiangular (its five angles are equal).

Cyclic pentagons[]

A cyclic pentagon is one for which a circle called the circumcircle goes through all five vertices. The regular pentagon is an example of a cyclic pentagon. The area of a cyclic pentagon, whether regular or not, can be expressed as one fourth the square root of one of the roots of a septic equation whose coefficients are functions of the sides of the pentagon.[11][12][13]

There exist cyclic pentagons with rational sides and rational area; these are called Robbins pentagons. In a Robbins pentagon, either all diagonals are rational or all are irrational, and it is conjectured that all the diagonals must be rational.[14]

General convex pentagons[]

For all convex pentagons, the sum of the squares of the diagonals is less than 3 times the sum of the squares of the sides.[15]:p.75,#1854

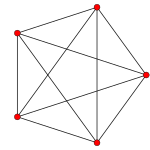

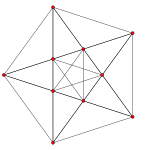

Graphs[]

The K5 complete graph is often drawn as a regular pentagon with all 10 edges connected. This graph also represents an orthographic projection of the 5 vertices and 10 edges of the 5-cell. The rectified 5-cell, with vertices at the mid-edges of the 5-cell is projected inside a pentagon.

5-cell (4D) |

Rectified 5-cell (4D) |

Examples of pentagons[]

Plants[]

Pentagonal cross-section of okra.

Morning glories, like many other flowers, have a pentagonal shape.

The gynoecium of an apple contains five carpels, arranged in a five-pointed star

Starfruit is another fruit with fivefold symmetry.

Animals[]

A sea star. Many echinoderms have fivefold radial symmetry.

Another example of echinoderm, a sea urchin endoskeleton.

An illustration of brittle stars, also echinoderms with a pentagonal shape.

Minerals[]

A Ho-Mg-Zn icosahedral quasicrystal formed as a pentagonal dodecahedron. The faces are true regular pentagons.

A pyritohedral crystal of pyrite. A pyritohedron has 12 identical pentagonal faces that are not constrained to be regular.

Artificial[]

The Pentagon, headquarters of the United States Department of Defense.

Home plate of a baseball field

Pentagons in tiling[]

A regular pentagon cannot appear in any tiling of regular polygons. First, to prove a pentagon cannot form a regular tiling (one in which all faces are congruent, thus requiring that all the polygons be pentagons), observe that 360° / 108° = 31⁄3 (where 108° Is the interior angle), which is not a whole number; hence there exists no integer number of pentagons sharing a single vertex and leaving no gaps between them. More difficult is proving a pentagon cannot be in any edge-to-edge tiling made by regular polygons:

The maximum known packing density of a regular pentagon is approximately 0.921, achieved by the double lattice packing shown. In a preprint released in 2016, Thomas Hales and Wöden Kusner announced a proof that the double lattice packing of the regular pentagon (which they call the "pentagonal ice-ray" packing, and which they trace to the work of Chinese artisans in 1900) has the optimal density among all packings of regular pentagons in the plane.[16] As of 2020, their proof has not yet been refereed and published.

There are no combinations of regular polygons with 4 or more meeting at a vertex that contain a pentagon. For combinations with 3, if 3 polygons meet at a vertex and one has an odd number of sides, the other 2 must be congruent. The reason for this is that the polygons that touch the edges of the pentagon must alternate around the pentagon, which is impossible because of the pentagon's odd number of sides. For the pentagon, this results in a polygon whose angles are all (360 − 108) / 2 = 126°. To find the number of sides this polygon has, the result is 360 / (180 − 126) = 62⁄3, which is not a whole number. Therefore, a pentagon cannot appear in any tiling made by regular polygons.

There are 15 classes of pentagons that can monohedrally tile the plane. None of the pentagons have any symmetry in general, although some have special cases with mirror symmetry.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

Pentagons in polyhedra[]

| Ih | Th | Td | O | I | D5d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dodecahedron | Pyritohedron | Tetartoid | Pentagonal icositetrahedron | Pentagonal hexecontahedron | Truncated trapezohedron |

See also[]

- Associahedron; A pentagon is an order-4 associahedron

- Dodecahedron, a polyhedron whose regular form is composed of 12 pentagonal faces

- Golden ratio

- List of geometric shapes

- Pentagonal numbers

- Pentagram

- Pentagram map

- Pentastar, the Chrysler logo

- Pythagoras' theorem#Similar figures on the three sides

- Trigonometric constants for a pentagon

In-line notes and references[]

- ^ "pentagon, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2014. Web. 17 August 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meskhishvili, Mamuka (2020). "Cyclic Averages of Regular Polygons and Platonic Solids". Communications in Mathematics and Applications. 11: 335–355.

- ^ Herbert W Richmond (1893). "Pentagon".

- ^ Peter R. Cromwell. Polyhedra. p. 63. ISBN 0-521-66405-5.

- ^ This result agrees with Herbert Edwin Hawkes; William Arthur Luby; Frank Charles Touton (1920). "Exercise 175". Plane geometry. Ginn & Co. p. 302.

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein (2003). CRC concise encyclopedia of mathematics (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 329. ISBN 1-58488-347-2.

- ^ DeTemple, Duane W. (Feb 1991). "Carlyle circles and Lemoine simplicity of polygon constructions" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 98 (2): 97–108. doi:10.2307/2323939. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-21.

- ^ George Edward Martin (1998). Geometric constructions. Springer. p. 6. ISBN 0-387-98276-0.

- ^ Euklid's Elements of Geometry, Book 4, Proposition 11 (PDF). Translated by Richard Fitzpatrick. 2008. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-6151-7984-1.

- ^ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275-278)

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Cyclic Pentagon." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. [1]

- ^ Robbins, D. P. (1994). "Areas of Polygons Inscribed in a Circle". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 12: 223–236. doi:10.1007/bf02574377.

- ^ Robbins, D. P. (1995). "Areas of Polygons Inscribed in a Circle". The American Mathematical Monthly. 102: 523–530. doi:10.2307/2974766.

- ^ *Buchholz, Ralph H.; MacDougall, James A. (2008), "Cyclic polygons with rational sides and area", Journal of Number Theory, 128 (1): 17–48, doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2007.05.005, MR 2382768, archived from the original on 2018-11-12, retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ Inequalities proposed in “Crux Mathematicorum”, [2].

- ^ Hales, Thomas; Kusner, Wöden (September 2016), Packings of regular pentagons in the plane, arXiv:1602.07220

External links[]

| Look up pentagon in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Pentagon". MathWorld.

- Animated demonstration constructing an inscribed pentagon with compass and straightedge.

- How to construct a regular pentagon with only a compass and straightedge.

- How to fold a regular pentagon using only a strip of paper

- Definition and properties of the pentagon, with interactive animation

- Renaissance artists' approximate constructions of regular pentagons

- Pentagon. How to calculate various dimensions of regular pentagons.

| hide | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | An | Bn | I2(p) / Dn | E6 / E7 / E8 / F4 / G2 | Hn | |||||||

| Regular polygon | Triangle | Square | p-gon | Hexagon | Pentagon | |||||||

| Uniform polyhedron | Tetrahedron | Octahedron • Cube | Demicube | Dodecahedron • Icosahedron | ||||||||

| Uniform polychoron | Pentachoron | 16-cell • Tesseract | Demitesseract | 24-cell | 120-cell • 600-cell | |||||||

| Uniform 5-polytope | 5-simplex | 5-orthoplex • 5-cube | 5-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 6-polytope | 6-simplex | 6-orthoplex • 6-cube | 6-demicube | 122 • 221 | ||||||||

| Uniform 7-polytope | 7-simplex | 7-orthoplex • 7-cube | 7-demicube | 132 • 231 • 321 | ||||||||

| Uniform 8-polytope | 8-simplex | 8-orthoplex • 8-cube | 8-demicube | 142 • 241 • 421 | ||||||||

| Uniform 9-polytope | 9-simplex | 9-orthoplex • 9-cube | 9-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 10-polytope | 10-simplex | 10-orthoplex • 10-cube | 10-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform n-polytope | n-simplex | n-orthoplex • n-cube | n-demicube | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 | n-pentagonal polytope | |||||||

| Topics: Polytope families • Regular polytope • List of regular polytopes and compounds | ||||||||||||

- Constructible polygons

- Polygons by the number of sides

- 5 (number)

- Elementary shapes