Pete McCloskey

Pete McCloskey | |

|---|---|

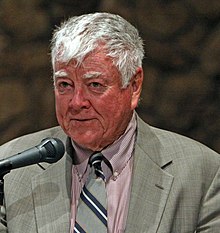

McCloskey in 2014 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California | |

| In office December 12, 1967 – January 3, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | J. Arthur Younger |

| Succeeded by | Ed Zschau |

| Constituency | 11th district (1967–73) 17th district (1973–75) 12th district (1975–83) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Paul Norton McCloskey Jr. September 29, 1927 Loma Linda, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (since 2007) |

| Other political affiliations | Republican (1948–2007) |

| Residence | Rumsey, California, U.S. |

| Education | Stanford University (AB, LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy (1945–1947) United States Marine Corps (1950–1952) U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (1952–1974) |

| Years of service | 1945–1964 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | Korean War |

| Awards | Navy Cross Silver Star Purple Heart (2) |

Paul Norton "Pete" McCloskey Jr. (born September 29, 1927) is an American politician who represented San Mateo County, California as a Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1983.[1]

Born in Loma Linda, California, McCloskey pursued a legal career in Palo Alto, California, after graduating from Stanford Law School. He served in the Korean War as a member of the United States Marine Corps. For his service, he was awarded the Navy Cross and the Silver Star. He won election to the House of Representatives in 1967, defeating Shirley Temple in the Republican primary. He co-authored the 1973 Endangered Species Act.[2] He unsuccessfully challenged President Richard Nixon in the 1972 Republican primaries on an anti-Vietnam War platform[2] and was the first member of Congress to publicly call for President Nixon's resignation after the Saturday Night Massacre.[3]

He continually won re-election until 1982, when he unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination to represent California in the United States Senate. The nomination was won by Pete Wilson, who went on to defeat Jerry Brown in the general election. During the 1988 Republican presidential primaries, McCloskey helped end Pat Robertson's campaign by revealing that Robertson's claims of serving in combat were false. In 1989, McCloskey co-founded the Council for the National Interest, non-profit, non-partisan organization that works for "Middle East policies that serve the American national interest."[4] He strongly opposed the Iraq War and supported Democrat John Kerry in the 2004 presidential election. In 2006, he made an unsuccessful run for Congress against Republican Richard Pombo. He endorsed Democrat Jerry McNerney in the general election and became a Democrat himself shortly thereafter.

He has written two books, Truth and Untruth: Political Deceit in America and The Taking of Hill 610: And Other Essays on Friendship.

Early life[]

Pete McCloskey's great-grandfather was orphaned in the Great Irish Famine and came to California in 1853 at the age of 16. He and his son, McCloskey's grandfather, were farmers in Merced County. The family were lifelong Republicans.[5]

McCloskey was born on September 29, 1927, in Loma Linda, California, the son of Mary Vera (McNabb) and Paul Norton McCloskey.[6][7] He attended public schools in South Pasadena and San Marino. He was inducted into South Pasadena High School Hall of Fame for the sport of baseball.[8] He attended Occidental College and California Institute of Technology under the U.S. Navy's . He graduated from Stanford University in 1950 and Stanford University Law School in 1953.

Military service[]

McCloskey voluntarily served in the U.S. Navy from 1945 to 1947, the U.S. Marine Corps from 1950 to 1952, the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve from 1952 to 1960 and the Ready Reserve from 1960 to 1967. He retired from the Marine Corps Reserve in 1974, having attained the rank of colonel.

He was awarded the Navy Cross and Silver Star decorations for heroism in combat and two Purple Hearts as a Marine during the Korean War.[2] He then volunteered for the Vietnam War before eventually turning against it.[2] In 1992, he wrote his fourth book, The Taking of Hill 610, describing some of his exploits in Korea.

Political career[]

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

McCloskey served as a Deputy District Attorney for Alameda County, California, from 1953 to 1954 and practiced law in Palo Alto, California, from 1955 to 1967, cofounding the firm that eventually became Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati. He was a lecturer on legal ethics at the Santa Clara and Stanford Law Schools from 1964 to 1967. He was elected as a Republican to the 90th Congress, by special election, to fill the vacancy caused by the death of U.S. Rep. J. Arthur Younger, after defeating Shirley Temple in the primary, and was reelected to the seven succeeding Congresses, serving from December 12, 1967 to January 3, 1983. In a 1981 interview, he stated that he thought he "was the first Republican elected opposing the war" despite the fact that his "constituency, two to one, favored the war in 1967".[9]

McCloskey was the first member of Congress to publicly call for the impeachment of President Nixon after the Watergate scandal and the Saturday Night Massacre. He was also the first lawmaker to call for a repeal of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that had allowed for the War in Vietnam.[2] He chose, in early 1975, to see for himself the effects of US bombing in Cambodia, stating afterwards that his country had committed "greater evil than we have done to any country in the world, and wholly without reason, except for our benefit to fight against the Vietnamese".[10]

McCloskey sought the 1972 Republican Presidential nomination on a pro-peace/anti-Vietnam War platform, and obtained 11 percent of the vote against incumbent President Richard M. Nixon in the New Hampshire primary. At the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, Rep. McCloskey received one vote (out of 1324) from a New Mexico delegate. All other votes cast went to President Nixon, which technically meant that McCloskey finished second place in the race for the Presidential nomination. Congressman John Ashbrook of Ohio had also challenged President Nixon's bid for re-nomination, albeit on a conservative platform.[11]

In 1982, McCloskey was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for nomination to the United States Senate. The California Republican Senatorial primary that year was a contentious battle among the major candidates in the 12-person GOP field, featuring mainly Reps. McCloskey, Bob Dornan, Barry Goldwater Jr. (son of Arizona Senator and 1964 Republican Presidential nominee Barry Goldwater), Maureen Reagan (daughter of then-President Ronald Reagan), San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson, former Rep. John G. Schmitz, and Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce president Ted Bruinsma. Wilson was the eventual victor and went on to defeat the Democratic candidate, then-Governor Jerry Brown, in the general election[12]

According to Paul Findley, McCloskey was hounded by the Anti-Defamation League, both during his political career and when he retired to private practice as a lawyer, for his outspoken views on Israel's attitude to Palestinians and on the Israel Lobby.[13]

Post-Congress[]

Debate on Israel-Palestinian issues[]

In 1986, McCloskey engaged in a debate about Israel-Palestinian issues with Jewish Defense League founder, Rabbi Meir Kahane.[14] McCloskey stated that two thousand people attended the debate which took place in San Francisco[15] and was eventually turned into a short film titled, "Why Terrorism?" produced by Mark Green.[16]

Pat Robertson presidential campaign controversy[]

McCloskey's revelation of Pat Robertson's lies about his Korean War service put an end to Robertson's 1988 Presidential run. Robertson first claimed that he was a "combat veteran" back in 1981, which aroused the ire of McCloskey, who had been shipped to Korea along with Robertson as second lieutenants as part as the 5th Replacement Draft to bolster the First Marine Division, which had suffered great losses at the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. McCloskey and Robertson were part of a contingent of 71 Marine officers and 1,900 enlisted men shipped to Korea aboard the USS General J.C. Breckenridge to serve as replacements.[17]

When Robertson began claiming again that he was a combat veteran during the 1988 Republican primaries, McCloskey wrote a public letter to U.S. Representative Andrew Jacobs Jr., also a Marine veteran of the Korean War, in which McCloskey said that Robertson was actually spared combat duty when his powerful father, U.S. Senator A. Willis Robertson of Virginia, intervened on his behalf, and that Robertson had actually boasted that his father would keep him out of combat. Robertson, a college friend, and four other second lieutenants were shipped to Japan, detailed to a training mission for Marines coming out of Korea. Of the remaining Marine officers, half were killed or wounded in combat.[17]

Robertson sued McCloskey and another accuser for libel, demanding damages of $35 million, but research underwritten by McCloskey that cost him $400,000 proved that his revelations were true. Rather than being a combat veteran, Robertson had been shipped to Japan right off the USS Breckenridge, then spent most of his time when returned to Korea and was posted at the safe harbor of the Division Headquarters. Robertson served as the Division "liquor officer", responsible for keeping the officers' clubs supplied with alcohol, which meant he kept traveling back to Japan. It was claimed that Robertson sexually harassed a Korean woman at one of his clubs and worried about getting gonorrhea. Documentary evidence uncovered by McCloskey revealed that his father, Senator Robertson, thanked Marine Commandant Robinson for getting his son out of combat. By the time of the libel trial, which was scheduled for Super Tuesday, many other Marine officers were prepared to testify that Robertson avoided combat duty. The day before the trial, Robertson dropped the libel suit. On Super Tuesday, he was punished at the polls. He later paid McCloskey's court costs.[17][18]

McCloskey wrote a book about his Korean War experiences, The Taking of Hill 610.

Council of the National Interest[]

In 1989, McCloskey co-founded the Council for the National Interest along with former Congressman Paul Findley.[19] It is a 501 (c)4 non-profit, non-partisan organization that works for "Middle East policies that serve the American national interest."[20][21] He taught political science at Santa Clara University in the early 1980s. For many years, he practiced law in Redwood City, California and resided in Woodside, California.

Iraq War[]

An opponent of the Iraq War,[22] McCloskey broke party ranks in 2004 to endorse John Kerry in his bid to unseat George W. Bush as President of the United States.[2]

2006 run for Congress[]

On January 23, 2006, McCloskey announced at a press conference in Lodi, California, that he would return to the political arena by running against seven-term incumbent Republican Richard Pombo in the Republican primary for California's 11th congressional district.[23] Earlier in the year, he formed a group called the "Revolt of the Elders" to recruit a viable primary candidate to run against Pombo. McCloskey's aging campaign bus sported the slogan "Restore Ethics to Congress." McCloskey said, "Congressmen are like diapers. You need to change them often, and for the same reason."[2] McCloskey was endorsed in the Republican Party primary by the San Francisco Chronicle[24] and the Los Angeles Times.[25] In the June 6, 2006, primary, McCloskey was defeated by Pombo, receiving 32 percent of the vote.[26]

On July 24, 2006, McCloskey endorsed Jerry McNerney, a Democrat who would go on to unseat Pombo in the 2006 midterm elections.[27] McCloskey spent most of Election Night at McNerney's victory party.[28] The Sierra Club recognized McCloskey for helping to unseat Pombo with their 2006 Edgar Wayburn Award.[29]

Change of political affiliation[]

In the spring of 2007, McCloskey announced that he had changed his party affiliation to the Democratic Party. In an email and letter to the Tracy Press, McCloskey stressed that the "new brand of Republicanism" had finally led him to abandon the party that he had joined in 1948.[30][31] He followed this up with an op-ed column in which he explained that "Disagreement [with party leadership] turned into disgust" and "I finally concluded that it was fraud for me to remain a member of this modern Republican Party", although it was a "decision not easily taken."[5]

In the 2020 United States presidential election, McCloskey was nominated to be a member of the Democratic slate of electors for the state of California.[32][33] As Democrat Joe Biden won the state's popular vote, McCloskey became one of California's 55 members of the Electoral College. He cast his presidential vote for Biden and vice-presidential vote for California Senator Kamala Harris on December 14, 2020.[34]

Political positions[]

McCloskey is pro-choice, supports stem cell research and Oregon's assisted suicide law. He was a co-chair of the first Earth Day in 1970.[2]

IHR/Holocaust controversy[]

Pete McCloskey gave the keynote address to the May 2000 Institute for Historical Review (IHR) Conference in Irvine, California. IHR is noted for denying the Holocaust. His speech, entitled “The Machinations of the Anti-Defamation League”, began “You might wonder why a man would leave northern California and come to southern California in the middle of a lovely weekend. I came because I respect the thesis of this organization.”[1] When he ran in the 2006 Republican Party primary for congress, there was controversy over exactly what he said about the Holocaust at the event. According to the San Jose Mercury News McCloskey said at the time, "I don't know whether you are right or wrong about the Holocaust," and referred to the "so-called Holocaust". McCloskey replied that he has never questioned the existence of the Holocaust, and the 2000 quote referred to a debate over the number of people killed.[35] McCloskey said in an interview with the Contra Costa Times on January 18, 2006, that the IHR transcript of his speech was inaccurate.[36] Journalist Mark Hertsgaard of The Nation, in response to criticism of an article he wrote praising McCloskey's campaign against Pombo, stated that a tape he had viewed of McCloskey's speech to the IHR did not contain the "right or wrong" wording present in the transcript.[37]

Family and personal life[]

McCloskey's first marriage was to Caroline; they had four children, Nancy, Peter, John, and Kathleen, before divorcing. He later married Helen V. Hooper.[38]

Bibliography[]

- McCloskey, Paul N. Truth and Untruth; Political Deceit in America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972. ISBN 067121201X OCLC 266811

- McCloskey, Paul N., and Helen Hooper McCloskey. The Taking of Hill 610: And Other Essays on Friendship. Woodside, Calif: Eaglet Books, 1992. OCLC 28194371

References[]

- ^ "McCLOSKEY, Paul Norton , Jr. (Pete) - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "White knight in a battle-bus". The Economist. 2006-06-01. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ "Pete McCloskey: Leading from the Front". The Video Project. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- ^ Ayoon Wa Aza, How Pro-Israeli Lobbies Destroy U.S. Interests, Dar Al Hayat, International edition, November 14, 2010, via Highbeam.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McCloskey, P. "Another Point of View: What Happened to the Party of Ford & Eisenhower?". (Auburn, Calif.) Sentinel, April 27, 2007.

- ^ Kennedy-Minott, Rodney (1968). "The Sinking of the Lollipop: Shirley Temple Vs. Pete McCloskey".

- ^ "The San Bernardino County Sun from San Bernardino, California on May 6, 1917 · Page 8".

- ^ South Pasadena High School Archived June 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ WGBH (1981-10-14). "Interview with Paul N. Mccloskey, 1981." WGBH Media Library & Archives, 14 October 1981. Retrieved on 2010-11-03 from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2010-11-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- ^ Logevall, Fredrik (2010). "The Indochina wars and the Cold War, 1945–1975". In Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, eds., The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Volume II: Crises and Détente (pp. 281–304). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83720-0.

- ^ Blair, William G. (1982-04-25). "Rep. John M. Ashbrook of Ohio Dies at Age of 53". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ Vassar, Alex; and Meyers, Shane (2013-07-01). JoinCalifornia: Election History for the State of California. 1 July 2013. Retrieved on 2013-07-01 from http://www.joincalifornia.com/candidate/5759.

- ^ Paul Findley, They Dare to Speak Out: People and Institutions Confront Israel's Lobby, Chicago Review Press, 2003 pp.54-61 p.59:'A tracking system initiated by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith (ADL) assured that McCloskey would have no peace, even as a private citizen.'

- ^ "RABBI MEIR DAVID KAHANE Debates SENATOR PETE McCLOSKEY". YouTube.

- ^ McCloskey, Paul N. Jr. (May 28, 2000). "Machinations of the Anti-Defamation League".

Now, I've always been willing to debate. I once debated Meir Kahane in front of two thousand Jews in San Francisco. I've debated Irv Rubin of the Jewish Defense League. But no ADL leader will debate me on the subject of Israel.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (August 26, 1986). "AN 'INTERCOM' DEBATE, 'WHY TERRORISM?'". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brady, James. "Pat Robertson Redux". Forbes. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Plummer, William and Dirk Mathison. "A Lawsuit Over Pat Robertson's War Record Has Ex-Marine Pete Mccloskey Fighting Mad". People Magazine. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Ayoon Wa Aza, How Pro-Israeli Lobbies Destroy U.S. Interests, Dar Al Hayat, International edition, November 14, 2010, via Highbeam.

- ^ CNI web site "About Us" page.

- ^ Delinda C. Hanely, CNI Cruises into a New Decade, Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, January 1, 2010, via Highbeam.

- ^ Mark Hertsgaard, A Dragon Slayer Returns, The Nation, posted March 9, 2006 (March 27, 2006 issue). Accessed June 20, 2006.

- ^ map Archived 2006-01-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McCloskey over Pombo, San Francisco Chronicle editorial, May 24, 2006.

- ^ James Taranto, From the WSJ Opinion Archives, Wall Street Journal, May 30, 2006.

- ^ Brian Foley, Pombo to face McNerney in November; Zone 7 candidates tight, Tri-Valley Herald, June 8, 2006. Accessed June 20, 2006.

- ^ McCloskey Bucks GOP, Backs Democrat[dead link], Washington Post, July 24, 2006

- ^ McNerney, enviros take down Richard Pombo Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Capitol Weekly, November 9, 2006

- ^ John Upton,Greens honor McCloskey, Tracy Press, November 25, 2006

- ^ Lisa Vorderbrueggen, McCloskey leaves Republican Party Archived April 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Contra Costa Times Politics Weblog, April 16, 2007

- ^ McCloskey, Pete (April 21, 2007). "McCloskey: Why I have switched political parties". Tracy Press. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on September 29, 2007.

- ^ https://www.archives.gov/files/electoral-college/2020/ascertainment-california.pdf

- ^ https://www.sacbee.com/opinion/article247837010.html

- ^ https://www.archives.gov/files/electoral-college/2020/vote-california.pdf

- ^ Mary Anne Ostrom, At 78, Spoiling for One Last Fight Archived 2006-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, San Jose Mercury News, February 20, 2006, reprinted on McCloskey's web site. Accessed online June 20, 2006.

- ^ Lisa Vorderbrueggen, McCloskey takes challenge to run against Pombo, Contra Costa Times, January 19, 2006. Archived May 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mark Hertsgaard, "'Dragon Slayer' No Saint George? Hertsgaard Replies", The Nation, May 1, 2006. Accessed July 04, 2008.[verification needed]

- ^ Pete McCloskey. NNDB. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

External links[]

- United States Congress. "Pete McCloskey (id: M000343)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-02-19

- McCloskey's letter endorsing McNerney, July 27, 2006

- Contra Costa Times story on McCloskey's party switch

- Pete McCloskey: Leading from the Front - documentary film aired July 5, 2009 on Truly CA: Our State, Our Stories - KQED

- McCloskey's participation in panel, The Shape and Mission of the U.S. Military: What's Ahead for America? at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library

- 1927 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American politicians

- 20th-century Presbyterians

- 21st-century Presbyterians

- American anti–Iraq War activists

- American conservationists

- United States Marine Corps personnel of the Korean War

- American people of Irish descent

- American Presbyterians

- California Democrats

- California Institute of Technology alumni

- California Republicans

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from California

- Military personnel from California

- Occidental College alumni

- People from Woodside, California

- Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Stanford University alumni

- United States Marine Corps officers

- United States Marine Corps reservists

- United States Navy officers

- Candidates in the 1972 United States presidential election

- Writers from California

- People from Loma Linda, California

- 2020 United States presidential electors