Philippine dance

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

| Life in the Philippines |

|---|

|

Philippine dance has played a tremendous role in Filipino culture. From one of the oldest dated dances called the Tinikling, to other folkloric dances such as the Pandanggo, Cariñosa, and Subli, and even to more modern-day dances like the ballet, it is no doubt that dance in the Philippine setting has integrated itself in society over the course of many years and is significantly imbedded in culture. Each of these dances originated in a unique way and serve a certain purpose, showcasing how diverse Philippine dances are now.

Types of dances by ethnic group[]

The following are various indigenous dances of the major ethnic groupings of the Philippines

Igorot[]

There are six Igorot ethnolinguistic tribes living in Luzon's mountain terrains: the Bontoc, Ifugao, Benguet, Apayo, and the Kalinga tribes, which retained much of their anito religions. Their lives have been centered on appeasing their gods and maintaining a harmonious relationship between spirits and man. Dances are usually linked to rituals for a good harvest, health, prayers for peace, and safety in war.[1]

| Type of Dance | Origin | Tribe | Purpose |

| Banga | Kalinga | One popular contemporary performance in the Philippines is named after the large banga pots. This performance originated in the province of Kalinga of the Mountain Province. As many as seven or eight pots are balanced on the heads of maidens as they move to the beat of the gangsa, a type of gong, while they go about their daily routine of fetching water while balancing the banga. This is why the tribesmen are known as fierce warriors.[1] | |

| Bendayan | Benguet Province, Northern Luzon | The Bendayan, which is also referred to as Bendian, is a dance that was adapted from the tradition of the Benguet Mountain Province in which hunters are honoured. Although it is an adaptation or rendition of the original, it is still included in each festivity in Benguet and its significance remains preserved. Furthermore, the circles lead to an unambiguous meaning.[1] | |

| Manmanok | Bago | Manmanok is a dance that dramatizes is a dance that portrait the rooster and the hen, Lady Lien. They try to attract her by making use of blankets that depict their feathers and wings.[1] | |

| Lumagen/Tachok | Luzon | Kalinga | Tachok is a Kalinga Festival Dance that is performed by unmarried Kalinga women who imitate the movement of the flight of birds as they move through the air. People come together and perform this dance to celebrate their birth first-born baby boy, weddings, or people who are able to make peace with each other. This dance is accompanied with music with the use of gongs.[1] |

| Turayen | Cagayan Valley | Gaddang | The word Gaddang originated from the combination of two words which are “ga”, meaning heat, and “dang” which is to burn. The Gaddang people live in the center of Cagayan Valley. Furthermore, some of their groups have resided in Isabela, Kalinga, and Eastern Bontoc. They are mostly Christian, and are agricultural in nature. Those that have resided in the areas stated mostly preserved their culture which is rooted in indigenous and swidden agricultural traditions. For an instance, they commonly practice the burning of existing crops to construct short-term plots for farming. Additionally, they also practice hunting and fishing. In the Gaddang dance, the people emulate the movements of birds that are drawn to tobacco trees.[1] |

| Tarektek | Benguet | Tarektek dramatizes two male tarektek woodpeckers who try to get the attention of three females. The first woodpecker tries doing this by showing his good voice. This was portrayed by the banging of a brass gong. On the other hand, the second tries impress the females by showing off his feathers. This was portrayed by the use of colorful blankets that are moved around in bird like movements.[1] | |

| Salidsid | Kalinga | The Salidsid, or the “cayoo dance”, is known as a romantic dance in which a male courts a female. That being said, it is commonly performed with one male and a female dancer. It starts with each of the dancers holding an “ayob” or “allap” which is a small cloth. Customarily, the most powerful people in the village are in the dance following the host's signal of the opening of the affair. Both the context and the significance of the dance are apparent. Additionally, the male imitates a rooster that is attempting to gain attention from a hen which is represented by a female dancer. On the other hand, the female dancer imitates the gestures of a hen that is being orbited by a rooster.[1] | |

| Salip | Kalinga | Tribes from the mountain provinces in Luzon give great importance to their identity. Thanksgiving, birth, wedding, and victory in war among others, are some things that these people celebrate through the art of dance. The Kalinga wedding ritual, to be particular, is a dance wherein a bride is offered protection and comfort by the groom. The man tries to show his love by imitating the movements of a rooster. Meanwhile, the bride's friends prepare “bangas” (earthen pots) that contain fresh water from the mountain spring to offer to the groom.[1] | |

| Ragsaksakan | Kalinga | Ragsaksakan dance portrays the walk of the industrious Kalingga women who climb up the rice terraces in the Mountain Provinces of the Philippines. They carry pots that are placed above their heads. They also wear small hand woven blankets around their necks which represent the “blankets of life.”[1] | |

| Uyauy/Uyaoy | Ifugao | Coined from the word ipugao meaning “coming from the earth” is the term Ifugao, pertaining to the people of the province who are called to be the “children of the earth.” As well as to the province itself, according to the Spaniards. Those who belong to the wealthy class, the Kadangyans, have the privilege to use the gongs that are used at the wedding festival dance. The same dance is performed by the people who desire to reach the second level of the wealthy class.[1] |

Moro[]

The Moro people are the various usually unrelated Muslim Filipino ethnic groups. Most of their dances are marked by intricate hand and arm movements, accompanied by instruments such as the agong and kulintang.[2]

| Type of Dance | Origin | Tribe | Purpose |

| Pangalay | Zamboanga del Sur | Badjao | The Panglay, a dance native to the Badjaos meant to highlight the power of the upper body, is executed through the rhythmic bounce of the shoulder while simultaneously waving the arms. Most times, this dance is performed in social gatherings like weddings.[2] |

| Burung Talo | Tausug | Burung Talo is a dance in the form of martial arts. Performers portray a battle between a hawk and a cat. This dance is accompanied with lively beats from gongs and drums as the performers do acrobatic movements.[3] | |

| Asik | Lanao del Sur | Maguindanao | The Asik is solo dance performance portrays an unmarried young woman who tries to gain the approval and support of her sultan master. She can dance for two reasons. The first is to try to win the heart of her master and the second is to be able to make up for a mistake she has done. In this dance, the performer dances and poses in doll like motionsand is dressed with fine beads, long metal finger nails, and heavy make up.[4] |

| Singkil | Lanao, Mindanao | Marano | Singkil is a Filipino dance that narrates the epic legend of “Darangan” of the Maranao people of Mindanao. This 14th century epic is about Princess Gandingan getting trapped in the forest during an earthquake that was said to have been caused by the forest nymphs or fairies called diwatas. The name “Singkil” is derived from the bells worn by the Princess on her ankles.

The dance uses props that are representative of the events in the epic. The criss-crossed bamboos are clapped together to signify the falling trees the Princess gracefully dodges as they fall while her slave follows her around. The Prince then finds her and the other dancers begin to dance slowly and progress to faster tempo with fans or their hands moving in a rhythmic manner which signify the winds in the forest. With skillful handling of fans, the dancers cross the bamboos precisely and expertly. In Sulu, Royal Princesses are required to learn the dance. The Royal Princesses in the dance, specifically in Lanao are usually accompanied by a waiting lady holding an elaborately decorated umbrella on her head and follows her as she dances.[2] |

| Tahing Baila | Yakan | Tahing Baila is a Yakan dance, a low land tribal Philippine folk dance, in which it tries to imitate movements of fish.[2] | |

| Pangsak | Basilan | Yakan | From the highlands of Mindanao, is a Musim ethnic group called the Yakan. They are known to wear body-hugging elaborately woven costumes. One of their popular dances, called Pangsak, involves a man and his wife performing complicated hand and foot movements while their faces are painted white to hide their identity from evil spirits.[2] |

| Panglay ha Pattong | Badjao | To imitate themovements of the beautiful southern boat (the vinta) with colorful sails which journeys through the Sulu Sea, the Panglay ha Pattong is a dance performed by a royal couple that balances on top of bamboo poles.[2] | |

| Panglay sa Agong | Tausug-Sulu | Panglay sa Agong is a dance that portrays two warriors who try to gain the attention of a young woman. By banging on gongs, it was the way they showed their courage and skills.[2] | |

| Pagapir | Lanao del Sur | Maranao | Maranao people from the around the Lake Lanao have a royal manner of “walking” called the Pagapir. The ladies of the royal court perform this dance for important events and to show their good upbringing. It involves a graceful manipulation of the Aper (apir) or fan while doing the “Kini-kini” or small steps.[2] |

| Sagayan | Cotabato | Maguindanao | Sagayan is a dance often performed before celebrations, and to get rid of bad spirits and to welcome good ones. The performers are fierce warriors who portray movements that depict a warrior trying to protect his master in battle. This means that many acrobatic movements are involved in this dance. They carry a shield on one hand and a kampilan on the other, a double-sided sword made of either wood or metal. These dancers also wear bright colored materials for their three tiered skirts, toppers and headgear.[2] |

| Kapa Malong Malong | Kapa Malong Malong, also known as Sambi sa Malong, is a dance that shows how the malong can be used or worn. A malong is a hand woven piece of cloth that is tubular that can come in many colors. For women, they usually make use of it as a skirt, shawl, mantle, or headpiece. On the other hand, for men, they make use of it as a sash, waistband, shorts or bahag, and headgear for the fields or as a decorative piece.[2] |

Lumad[]

The non-Islamized natives of Mindanao are collectively known as the Lumad people. Like the Igorot, they still retain much of their animistic anito religions.[5][6]

| Type of Dance | Origin | Tribe | Purpose |

| Kuntaw | T’boli | The Kuntaw, which originates from the Malay word meaning “fist”, is one of Mindanao's best-kept secrets. It is a martial arts dance that includes gestures of the fist, accompanied by other actions like jumps, kicks, and knee bends.[7] | |

| Kadal Taho | Lake Sebu, South Cotabato | T’boli | The tribe of T’boli is located in a place where there are vast amounts of wildlife, most especially birds. Kadal Taho, also considered as the “True Dance of the T’boli,” is a story about a flock of sister birds who left to look for food and ended up getting lost. During the journey, one of the sisters injures her leg and is unable to fly. With her flock by her side, motivating her and supporting her, she was able to fly again and they were able to get home safely.[8] |

| Kadal Blelah | Lemlosnon, Cotabato | T’boli | Kadal Blelah is a tribal dance wheres dancers try to simulate and imitate the different movements of birds.[5] |

| Binaylan | Higaonon | Bagobo | The Binalayan dance emulates movements of a hen, her baby chicks and a hawk. The hawk has always been seen and symbolized as that which has power over the welfare of the entire tribe. Although, one day, the hawk tried to get one of the baby chicks which led to the hawks death for it was killed by hunters.[5] |

| Bagobo Rice Cycle | Davao del Sur | Bagobo | Bagobo Rice Cycle, also known as Sugod Uno, is a tribal dance which portrays the rice production cycle. This includes the prepping the land, planting rice, watering the rice, and harvesting it. This dance also portrays rituals to say thank you for the rice that they were able to harvest.[9] |

| Dugso | Bukidnon | Talaindig | Performances such as a sacrifice dance rite exists in provinces wherein religion is given the highest regard, such as the Higaonon of Bukidnon province in Mindanao place. “Dugso” is performed as a form of thanksgiving for good harvest, healing of the sick and for the community's overall well being. It is also used to get rid of bad spirits, to give luck for victory in battle and used during the blessing of the newly opened field. Their costumes are compared to that of the pagpagayok bird because of the colourful headdresses and the bells wrapped around their ankles which is considered as the “best music” to the spirits.[8] |

| Kadal Heroyon | Lake Sebu, South Cotabato | T’boli | Kadal Heroyon, also known as the dance of flirtation, is performed by T’boli girl adolescents qualified to get married. Beautification, which was held of high importance in the tribe, is portrayed through movements that would imitate how birds flew.[5] |

| Karasaguyon | Lake Sebu, South Cotabato | T’boli | Karasaguyon is a tribal dance that portrays a story of four sisters who try to get the attention of a polygamous man who is choosing his next wife. This dance is accompanied with music from the sounds of the beads and bells as they clink against each other which are wrapped around the waists and ankles of the performers.[8] |

| Kinugsik Kugsik | Santa Maria, Agusan del Norte | Manobo | The Kinugsik Kugsik tries to imitate the friendly and endearing nature of squirrels. The dance portrays an issue of love between two male squirrels and one female squirrel who run around the forest. They had created this dance as a remembrance of the time wherein the tribe of Manobo lived harmoniously with squirrels who thrived in their area. They named this dance as such because they called these squirrels, “kugsik.”[8] |

| Lawin-Lawin | Davao del Sur | Bagobo | A lawin, Philippine hawk eagle, is endemic to the Philippine region. The lawin-lawin dance tries to imitate how the eagle soars the sky by making use of shields to represent the wings. This is performed by males of the Bagobo tribe.[8] |

| Sohten | Zamboanga del Norte | Subanon | Sohten was danced before as a way of asking the gods for protection and success before going into battle. This is now performed by an all males of the Subanon tribe who make use of shields and palm leaves to portray this pre-combat ritualistic dance.[8] |

| Talbeng | Babuklod, Florida Blanca, Pampanga | Talbeng, a lively dance accompanied by a guitarist, imitates animals of the region, most especially the monkeys. This dance originated from the Aetas, also known as the Negritos.[8] | |

| Bangkakawan | Bukidnon | Monobo | The Bangkakawan, a fishing ritual, originated from the Tigwahanon Manobos of Bukidnon. A huge log is carved to replicate the shape of a palungan (snake) and is used to making steady beats and rhythms to make fish dizzy and less difficult to catch.[10] |

| Maral Solanay | Southern Mindanao | B’laan | Moral Solanay is a dance performed by indigenous people of B’laan. This dance is performed by women who portray the spirit of a young lady named Solanay. Through this dance, they try to show grace, beauty, and diligence which Solanay represents.[11] |

| Basal Banal | Palawan | Palawanon | After a Pagdiwata ritual, the basal banal dance is usually performed. This is a traditional dance of the Palawanons wherein they make use of native balasbas and cloth to make their movements more prominent and noticeable.[12] |

| Palihuvoy | Manobo | Well respected Obo Manobo warriors, called Baganis, perform this dance which showcase their skills in fighting.[13] | |

| Sabay Pengalay | Zamboanga del Norte | Subanon | Sabay Pengalay is a Subanon courtship dance that contains pantomimic gestures. It portrays a smitten bachelor who tries to win the heart of a kerchief.[14] |

| Siring | Maguindanao | Lambangians | Siring is a dance performed by the Lambangian tribe. Their ancestry is from an intermarriage between the Dulangan Manobo and Teduray, two other indigenous tribes. The siring is a dance that portrays different activities that occur in their everyday lives. These include planting rice and catching fish.[15] |

| Sout | Zamboanga | Subanen | Sout is a Subanen dance which aims to be able to showcase a warriors skill with the use of a sword and shield (k’lasag) which are covered with different kinds of shells called blasi.[16] |

| Talek | Zamboanga | Subanen | Talek in a dance usually performed by Subanen women, who hold on to kompas or rattan leaves, during festivals or wedding celebrations.[17] |

| Kadal Unok | Lake Sebu, South Cotabato | T’boli | The Kadal Unok is a dance performed by women that is depicted through elegant and fluid movements with the use of the arms that tries to imitate the movements of the onus bird. They performers make use of heavy make up and adornments which represents the tribes passion for beauty and fashion. There passion for beauty and fashion goes as far as wearing wide brimmed hats that are highly decorated in the fields and wearing interlocked bronze belts, helots, whenever they walk or dance.[18] |

| Balisangkad | Tagbanau | Balisangkad comes from Madukayan, eastern side of Mountain Province. It is a type of hunting dance in which the dancers movements imitate those of an eagle, particularly the flight of the eagle.[19] | |

| Pagdiwata | Tagbanau | A ritual meant for the rice harvest, the Pagdiwata was a nine-day demonstration among the Tagbanuas of Palawan to give thanks. This revolved around the babaylan or priestess and her ministrations.[20] | |

| Sagayan | Tagbanau | The Sayagan is a dance meant for courtship wherein a man asks for a womans hand by putting his piz cloth on the ground. For the woman to answer him back, she must likewise put her own cloth on the ground.[21] | |

| Soryano | Palawan | Tagbanau | Soryano is a courtship dance that portrays anxious men holding on to cloths trying to persuade women to turn around and face them. Instead, these women, turn the opposite way for fun and make the men chase them.This dance then becomes a lively and energetic dance of chase.[22] |

| Tambol | Tagbanau | During the tambol, villagers summon their guiding spirit, Diwata. It is a nine-day ritual of a babaylan or priestess.[23] |

Christianized Filipinos[]

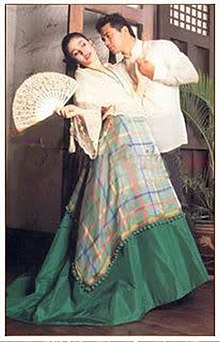

The majority of Filipinos are the Christianized lowlanders of the islands. Their dances are heavily influenced by the Spanish, though still retaining native aspects. The dances range from courtship dances, to fiesta (festival) dances, to performance dances. The traditional attire in these dances include the balintawak and patadyong skirts for the women, and camisa de chino and colored trousers for the men.[24]

| Type of Dance | Origin | Tribe | Purpose |

| Bulaklakan | Bulacan | The name Bulaklakan originates from the numerous flowers that grow in the area of Bulacan. The dance is dedicated to the Virgin Mary performed widely in the month of May as part of the celebration of their holy week.[25] | |

| Sakuting | Abra | Sakuting was originally performed by male dancers only. It originates from the province of Abra, performed by both Ilokano Christians and non Christians. It depicts a mock fight with sticks for training and combat. During Christmas, the dance is performed in town plazas or dancers will go door to door. Spectators give them aguinaldos (5-piso bills) or refreshments.[26] | |

| Tiklos | Leyte | For the past centuries, an important part of peasant social life is the gathering of peasants who collectively work together to do labor-intensive jobs for the community. Once a week they would gather to clean the forest, till the soil, do farm work, etc. Every noon time, after the peasants have eaten and started to rest, the Tiklos is usually performed. When the peasants start to hear the Tiklos music from the flute, guitar, guimbal or tambora, they start dancing the Tiklos together.[27] | |

| Abaruray | Social gatherings in communities call for customaries that come in the form of offering wine to guests. The offer is made by a young lady who chooses a young man from the guest to dance with. In accepting a glass of wine, the young man also accepts dancing with the lady. It is not advisable to turn down the offer as it is offensive to the community's etiquette and the lady. As they dance, the girl's ability is shown through balancing the glass of wine without spilling a drop. The audience claps with the music.[28] | ||

| Maglalatik | In the separation of Loma and Zapote of Binan, Laguna during the Spanish regime, the two barrios danced the maglalatik. The Maglalatik or Magbabao is a war dance in portrayal of a fight over prized latik between Moros and Christians. There are four parts of the dance, namely, the Palipasan and Baligtaran, Paseo and Sayaw Escaramusa. In order, the former two parts depicts the heated relationship between the two groups mentioned previously while the latter two parts showcases their reconciliation. Following the legend, the Moros won in the fight, but the Christians, uncontented, sent an envoy and offered peace and baptism to the Moros.

The dancers go house to house to dance the Maglalatik in exchange for money or a gift. Come night time, the dancers dance in a religious procession as an offering to San Isidro de Labrador, patron saint of the farmers.[29] | ||

| Tinikling | Leyte | The tinikling is named after the tikling bird. The dancers imitate the bird's flight in grace and speed as they play and chase each other, run over tree branches or dodge farmer's traps. The dance is done with a pair of bamboo poles.[citation needed]

The tinikling dance has evolved from what is called ‘Tinikling Ha Bayo’ which the older people claim to be a harder dance to perform. Originally, the said dance was done between bayuhan, wooden pestles used to pound husks off of rice grain.[30] | |

Subli |

Barrio of Dingin, Alitagtag, Batangas | Subli is a famous dance in barrios of the municipality of Bauan, Batangas. It is a ceremonial dance performed in fiestas every May in homage to Mahal Na Poong Santa Cruz.[29]

The name comes from the Tagalog words “subsub” (stooped) and “bali” (broken). Hence, the male dancers are positioned in a “trunk-forward-bend” way seemingly lame and crooked throughout the dance.[citation needed] | |

| Sayaw Sa Obando | Obando, Bulacan | The Sayaw sa Obando is performed in honor of Santa Clara, patron saint of the childless. It is the childless women usually from Malabon and Navotas who participate in the dance as part of a ritual to ask the said saint to grant their wishes to have a child.[27] | |

| Cariñosa | Cariñosa or Karinyosa is a well known dance around the Philippines with the meaning of the word being affectionate, lovable, and amiable. The dancers use a handkerchief and go through the motions of hide and seek or typical flirtatious and affectionate movements. The dance comes in many forms but the hide and seek is common in all.[31] | ||

| Kuratsa | During the Spanish regime, Kuratsa was one of the popular and best liked dances in the country. There are many versions across different regions in Ilocos and Bicol. Currently, the one being performed is a Visayan versions from Leyte. Performed in a moderate waltz style, the dance has a sense of improvisation that mimics a young playful couple trying to get each other's attention.[27] | ||

| Pandanggo Sa Ilaw | Lubang Island, Mindoro, Visayas | Coming from the Spanish word “fandango”, the dance is characterized by steps and clapping that varies in rhythm in 3/4 time. The Pandanggo sa Ilaw demands three oil lamps balanced on the heads and the back of the hands of each dancer.[32] |

Impact of societal functions to choreography[]

Other less common presentations of Philippine dances have been categorized by intention, or societal functions. Philippine dances not only convey the artistry of movement, but are often associated with life-functions such as weddings, the mimicry of birds, or even rituals like the warding of evil spirits. This outlook on dance can be separated into the following categories:

Ritualistic dances[]

Filipino rituals are based on the belief that there exists a delicate balance between man and nature, and the spirit world; and that it is through rituals that we can restore, enhance or maintain this balance. It clarifies our place in the universe; each gesture and move in the dance are symbolically articulating the role of man and human in the world. The dances contain narratives which illustrate the contractual obligations governing relationships between mankind, nature and the spirits. Because there are innumerable reasons for why and how humans can cause shifts in the balance or forget their place in the grander scheme, there are also innumerable rituals that can correct or address the concerns. Thus, it is in looking at their intentions that it can be better understood, interpreted and classified. Some of the rituals attempt to define the future, appease spirits, ask for good harvests, invoke protection, heal the sick, asking for good luck, guidance and counsel. Almost every facet of Filipino life is linked to a ritual practice and is an indication of the value and pervasiveness of rituals in folk culture.

Filipino rituals are often shown in dance, because for Filipinos, dance is the highest symbolic form. It transcends language and is able to convey emotions, collective memory, and articulate their purpose. Dance in this case, is the fundamental expression of their complex message and intention. Aside from ritualistic dance as a way to convey their request to the gods or spirits, it also reaffirms social roles in village hierarchies. The leaders of the dances are the masters of the village's collective memory and knowledge and subsequently, commands the highest respect and status.[33]

Forms[]

Rituals have been greatly influenced by rich colonial history, as well as archipelagic geography. As a result of this, each major geographic area such preserved distinct traditions, some preserving pre-colonial influences, while others were integrated or completely changed. Islam was deeply rooted in Mindanaoan culture long before the Spanish arrived and were mostly left untouched by Spanish presence, thus they continued to keep their mythic Islamic practices. Unlike the Filipinos of the lowlands, who integrated Christian and Catholic practices to form a uniquely Filipino folk Christianity which is still practiced today.[33]

Structure[]

As rituals are mostly in the form of dances, it uses gestures, incantations and symbolic implements to invoke spirits, to restore balance or to ask for intercession for harvests, good marriages, safety in journey or counsel. Rituals then, have 2 intended audiences, the spirits who are summoned to placate their anger or to call for their participation to restore balance and to care and provide for mankind. The second audience are the practitioners. In carrying out the rituals, they are reflecting and passing on the collective knowledge and memory of the village, which have been accumulated and refined across many generations. It is through the use of dramatic gestures and dance that symbolic narratives, their values and beliefs are recorded and safeguarded from forgetting. The performance of ritual dances is ultimately an act of recollection. It is a reminder for men and spirit their duties and responsibility in restoring the world's balance. And within the dance itself, practitioners are reminded of the significance of the past, and are being prepared to accommodate the uncertainties that the present and future may bring.[33]

Functions[]

Dancing for Filipinos have always imitated nature and life, and is seen as a form of spiritual and social expression. Birds, mountains, seas and straits have become inspiration for local dances. The tinikling mimic the rice-preying birds, the itik-itik is reminiscent of its namesake the duck, the courtship dances of the Cordillera are inspired by hawk-like movements.

Geographic location also influence what movements are incorporated into the dances. People from Maranao, Maguindanaon, Bagobo, Manobo, T’boli of Mindanao and Tausug and Badjao of Sulu. Draw influences from aquatic life as they are near bodies of water and have lived their lives mostly off-shore. Their dances accompanies by chants, songs and instruments like the kulintang, gong, gabbang and haglong, as well as a variety of drums show their zest for life.

Some rituals are used as religious expressions to honor the spirits and ask for blessings in each facet of life, such as birth, illness, planting, harvest or even death. They believe in diwatas, or spirits dwelling in nature, which can be appeased through offerings and dance as a means to commune with the spirit.[34]

Dance over the years[]

To better understand these dances, the time period of these dances must be considered. Depending on each period, they have had their own ways of influencing and inspiring the dances which then evolve and change depending on these elements.

Pre-colonial[]

Pre-colonial dances are distinctly meant to appease the Gods and to ask favors from spirits, as a means to celebrate their harvest or hunt. Their dance mimicked life forms and the stories of their community. Moreover, theses dances were also ritualistic in nature, dances articulated rites of passages, the community's collective legends and history.[35]

Across the 7,641 islands in the Philippines, there are various tribes scattered all over, each with their own unique traditions and dances. The Igorots from the mountains of Luzon, resisted Spanish colonization and influences have kept most of their dances untouched across generations. Their dances express their love of nature and gratitude to the gods. Their choreography imitates nature and their life experiences. Dancers would often swoop their arms like birds and stomp their feet as a representation of the rumbling earth.[36]

Spanish era[]

Spaniards have moderated and even led the politics and economics of the country,[37] which was mainly due to the Spanish colonialism starting from the 16th century. Despite the earliest Filipinos having their of type of government, writing, myths, and traditions, several features of Hispanic culture have influenced different aspects of Filipino culture, from clothing, such as the barong Tagalog and the terno, to their religion even up to the dances and music.[38]

Filipinos already had their own set of music and dances before the Spaniards came; dances were performed for different reasons, from weddings up to religious feasts, even to prepare for or celebrate war. As the Spanish colonizers realized the relevance of these dances for Filipinos, dancing was utilized as a relevant social activity. Some of the first dances they presented were the rigodon, Virginia, and lanceros; these were dances done for the higher class and special fiestas.[39] Filipino dance styles like the kumintang, type of song and dance, and dances like the Pampangois, a dance distinguished for its lion-like actions and hand clapping, were pushed aside when the Spaniards had come. However, they were later remade with influences from new Spanish dances such as the fandango, lanceros, curacha, and rigodon.[40] Other features that were done when adopting these European dances was the addition of local elements like using bamboo, paypays (local fans), and coconut or shell castanets.[41]

Filipinos, mainly aristocrats, have also created their own renditions of European dances such as the jotas, fandangos, mazurkas, and waltzes that were done during this time.[38] The fandango after it was introduced was recreated as the pandaggo; the same happened to the jota that was then recreated in several regions; Cariñosa and Sayaw Santa Isabel had steps that were taken from a popular dance, the waltz. Other examples would be how the rhythm and tempo of the jota and the polka influenced traditional dances like the Tinikling and the Itik-itik, which were also inspired from Southeast Asian dances. Dances that were not accompanied by Western music were also given their own accompaniments, such as the case of Pandanggo sa Ilaw.[37]

As European dances had more sharp and fast steps, Filipinos softened these movements when they were recreated.[39] Other dances that were created during the time of hispanization would be the Danza, Jota Cagayan, Jota Isabela, Pantomina, Abaruray, Jota Manileña, Habanera Jovencita, Paypay de Manila, Jota Paragua, and the Paseo de Iloilo.[38]

American era[]

Just like in the Spanish colonization, the Americans, in 1898, had brought in their own commercial and global culture which had also influenced the Filipinos. Those with interest in dance were the ones mainly appealed to by the more Black-influenced customs of dance and music. With these Filipino dancers who already know the zarzuela (sarswela), a Spanish form of stage performance with singing and dancing and musical comedy,[42] they became more interested in the American vaudeville (bodabil) or “stage show”, which is filled with both theatrical and circus acts, and more reminiscent of Broadway musicals.[43] More dynamic dances were incorporated in these zarzuelas during the 1950s to the 1970s, such as the cakewalk, buck-and-wing, skirt dance, clog, tap, and soft-shoe[42] that were more upbeat and had an American rhythm to them, as well as social dances like the Charleston, foxtrot, big apple, one-step, slow-drag, rumba, mambo, samba, cha-cha, and the Latin-influenced tango.[42] This growth of American-influenced dances also spawned the increase of cabarets, such as the Santa Ana Cabaret which is a huge ballroom dedicated for these performances. The disco scene also grew more in the 1980s.[43]

Known as the “Dean of Philippine vaudeville,” John Cowper had brought with him other artists when he had come. As with the growth of American influence over dance in the country, Filipinos had started creating their own dance troupes; some of these would be the Salvadors, the Roques, Sammy Rodrigues, Lamberto Avellana, and Jose Generoso to name a few.[42] European classical ballet also gained more popularity following the American dances. Aside from creating their own groups, with the new and more advanced transportation system in the country, the Philippines was now able to be included in the international circuit, which had led to performances by international acts such as the Lilliputians with their “ballet girls” and the Baroufski Imperial Russian Circus showcasing their ballerinas. Aside from having international acts come, other talents also came to perform, with the notable one being Anna Pavlova in 1922 and performed at the Manila Grand Opera House. More international acts came to perform in the Philippines after, while some also trained Filipino dancers, one of which is Madame Luboc “Luva” Adameit who trained some of the first notable ballet dancers who had also become choreographers: Leonor Orosa Goquingo, known for her folk-inspired ballet performances (such as Filipinescas), Remedios “Totoy” de Oteyza, and Rosalia Merino Santos, a child prodigy known for doing the first fouettes in the country.[43]

Aside from the rise of American dances and European style ballet, modern dance had also started taking form during this period in the vaudeville circuit. Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, two founders of modern dance visited the Manila in 1926. Other modern dancers also performed in the country which led to some Filipinos training under this dance style. With the growing popularity of this dance style, Filipino dancers continued to mix in elements of folklore and native themes. Anita Kane produced Mariang Makiling in 1939 and it was the first full-length Filipino ballet performance. She also has other works such as Reconstruction Ballet, Mutya ng Dagat (Muse of the Sea), Inulan sa Pista (Rained-out Feast), and Aswang (Vampire), which all had Filipino motifs. Leonor Orosa-Goquingco also had native elements in her dances like Noli Dance Suite and Filipinescas: Philippine Life, Legend and Lore in Dance, which had mixed ballet and folk dances into one performance. Due to this trend, many other writers and dancers continued to connect this Western dance style with native influences, motifs, and even history.[43]

Modern era[]

The Bayanihan Philippine National Folk Dance Company has been lauded for preserving many of the various traditional folk dances found throughout the Philippines. They are famed for their iconic performances of Philippine dances such as the tinikling and singkil that both feature clashing bamboo poles.[44]

See also[]

- Francisca Reyes-Aquino

- Leonor Orosa-Goquingco

- Lucrecia Reyes Urtula

- Ramon Obusan

- Alice Reyes

- Tinikling

- Cariñosa

- Maglalatik

- Pangalay

- Sagayan

- Singkil

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k "Philippine Dances Cordillera". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Muslim Mindanao dances". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Burung-Talo,origin country Philippines,The dance is a unique fighting dance in a form". www.danceanddance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Culture of the Philippines: Asik Dance". Culture of the Philippines. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "tribal dances". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "LUMAD SUITE". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ "Kadal Blidah". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Lumad". Hiyas.

- ^ Pinoy, Dance. "Bagobo Rice Cycle". Dance Pinoy. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Bangkakawan". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Maral Solanay". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Basal Banal". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Palivuhoy". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Sabay Pengalay". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Siring". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Sout". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Talek". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Kadal Unok". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Balisangkad". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Pagdiwata". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Sagayan". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Soryano". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Tambol". www.kaloobdance.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Dances of the Philippine CountrysideDances that are best known". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ "Bulaklakan". Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "The Sakuting – Dolores Online". Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Dances of the Philippine CountrysideDances that are best known". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ cherryhoney1818 (October 7, 2017). "Folk Dance in LUZON". Cultural dance in the Philippines. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "sa nayon". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Filipino-American Talent Showcase 2010". www.filamcultural.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Pinoy, Dance. "Cariñosa". Dance Pinoy. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Pandanggo Sa Ilaw". Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Rituals in Philippine Dance". National Commission for Culture and Arts.

- ^ "Philippine Ethnic Dances". National Commission on Culture and the Arts.

- ^ Theater, Benna Crawford BA. "Philippine Folk Dance History". LoveToKnow. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ "The History of Dance in the Philippines". www.eslteachersboard.com. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Philippine Dance in the Spanish Period". National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "spanish influence dances". www.seasite.niu.edu. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Spanish Colonial Tradition in Philippine Dance" (PDF).

- ^ "Folk Dances With Spanish Influence". ImbaLife. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Philippine Dance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Philippine Dance in the American Period". National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Philippine Dance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ Rowthorn, Chris & Greg Bloom (2006). Philippines (9th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-74104-289-4.

- Dance in the Philippines