Agriculture in the Philippines

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2021) |

Agriculture in the Philippines is an important part of the economy of the Philippines with crops like rice, coconut and sugar dominating the production of crops and exports. It employs 23% of the Filipino workforce as of 2021, according to the World Bank.[1]

The Philippines is one of the most vulnerable agricultural systems to monsoons and other extreme weather events,[2] which are expected to create more uncertainty as climate change effects the Philippines. However, the Food and Agriculture Organization has described the local policy measures as some of the most proactive in risk reduction.[3]

History[]

Profession[]

In the Philippines, the professional designation is "licensed agriculturist" (L.Agr.)[11]. They are licensed and accredited after successfully passing the Agriculture Licensure Examination. A prospective professional agriculturist is typically required to have a four-year bachelor of science degree in agriculture (general course), although other degree programs directly-related to agriculture are also allowed to take the licensure examination.[12] About 5,500 registered agriculturists pass the licensure examination annually.[13]

The primary role of agriculturists are to prepare technical plans, specifications, and estimates of agriculture projects such as in the construction and management of farms and agribusiness enterprises.[14] The practice of agriculture also includes the following:

- Consultation, evaluation, investigation, and management of agriculture projects

- Research and studies in soil analysis and conservation, crop production, breeding of livestock and poultry, tree planting, and other biotechniques

- Conduct training and extension services on soil analysis and conservation, crop production, breeding of livestock and poultry, tree planting

- Teaching of agriculture subjects in schools, colleges, and university

- Management of organizations related to agriculture, both in private and government (eg. Office of the Provincial Agriculturist)

The agriculturist profession and its board of agriculturists were created in 2002 by the Professional Regulation Commission,[12] in order to "upgrade the agriculture and fisheries profession"[15] by the virtue of the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act of 1997.

The practice of the agriculture profession is a professional service admission. Similar to other professions in the Philippines, malpractice and illegal practice of agriculture are grounds for suspension or revocation of certificates of registration and professional licenses.[16]

Licensed agriculturists in the Philippines are integrated into one accredited integrated professional organization, which is the Philippine Association of Agriculturists.Grains[]

Rice[]

The Philippines is the 8th largest rice producer in the world, accounting for 2.8% of global rice production.[17] The Philippines was also the world's largest rice importer in 2010.[18] In 2010, nearly 15.7 million metric tons of palay (pre-husked rice) were produced.[19] In 2010, palay accounted for 21.86% percent of gross value added in agriculture and 2.37% of GNP.[20] Self-sufficiency in rice reached 88.93% in 2015.[21]

Rice production in the Philippines has grown significantly since the 1950s. Improved varieties of rice developed during the Green Revolution, including at the International Rice Research Institute based in the Philippines have improved crop yields. Crop yields have also improved due to increased use of fertilizers. Average productivity increased from 1.23 metric tons per hectare in 1961 to 3.59 metric tons per hectare in 2009.[17]

Harvest yields have increased significantly by using foliar fertilizer (Rc 62 -> 27% increase, Rc 80 -> 40% increase, Rc 64 -> 86% increase) based on PhilRice National Averages.[citation needed]

The government has been promoting the production of Golden rice.[22]

The table below shows some of the agricultural products of the country per region.[23]

| Region | Rice | Corn/maize | Coconut | Sugarcane | Pineapple | Watermelon | Banana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilocos Region | 1,777,122 | 490,943 | 39,463 | 19,512 | 197 | 26,936 | 43,164 |

| Cordillera (CAR) | 400,911 | 237,823 | 1,165 | 51,787 | 814 | 141 | 26,576 |

| Cagayan Valley | 2,489,647 | 1,801,194 | 77,118 | 583,808 | 35,129 | 7,416 | 384,134 |

| Central Luzon | 3,304,310 | 271,319 | 167,737 | 678,439 | 1,657 | 7,103 | 58,439 |

| NCR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Calabarzon | 392,907 | 64,823 | 1,379,297 | 1,741,706 | 88,660 | 2,950 | 96,306 |

| MIMAROPA | 1,081,833 | 125,492 | 818,146 | 0 | 448 | 3,192 | 168,299 |

| Bicol Region | 1,264,448 | 243,908 | 1,105,743 | 239,010 | 130,595 | 5,598 | 76,452 |

| Western Visayas | 1,565,585 | 213,362 | 294,547 | 1,682,940 | 12,687 | 83,336 | 200,222 |

| Negros Island Region | 557,632 | 185,747 | 274,315 | 13,440,259 | 9,468 | 546 | 157,974 |

| Central Visayas | 269,801 | 101,333 | 274,069 | 241,573 | 998 | 1,161 | 126,220 |

| Eastern Visayas | 955,709 | 91,145 | 1,165,867 | 179,363 | 7,186 | 670 | 227,223 |

| Zamboanga Peninsula | 661,775 | 220,180 | 1,682,121 | 107 | 1,657 | 638 | 281,856 |

| Northern Mindanao | 725,120 | 1,216,301 | 1,851,702 | 3,065,463 | 1,468,386 | 2,024 | 1,832,173 |

| Davao Region | 441,868 | 224,100 | 2,246,188 | 208,743 | 26,880 | 1,070 | 3,455,014 |

| Soccsksargen | 1,291,644 | 1,239,275 | 1,159,818 | 680,383 | 794,334 | 2,132 | 1,159,091 |

| Caraga Region | 653,431 | 118,774 | 804,722 | 0 | 2,682 | 3,010 | 259,738 |

| ARMM | 488,215 | 673,036 | 1,393,168 | 113,343 | 921 | 80 | 531,048 |

Corn/maize[]

Corn/maize is the second most important crop in the Philippines. 600,000 farm households are employed in different businesses in the corn value chain. As of 2012, around 2.594 million hectares (6.41×106 acres) of land is under corn cultivation and the total production was 7.408 million metric tons (8.166×106 short tons).[24] The government has been promoting Bt corn for hardiness against insects and higher yields.[22]

Other food crops[]

Chocolate[]

Coffee[]

Coffee production in the Philippines began as early as 1740 when the Spanish introduced coffee in the islands. It was once a major industry in the Philippines, which 200 years ago was the fourth largest coffee producing nation.

As of 2014, the Philippines produces 25,000 metric tons of coffee and is ranked 110th in terms of output. However local demand for coffee is high with 100,000 metric tons of coffee consumed in the country per year.[26]

The Philippines is one of the few countries that produce the four main viable coffee varieties; Arabica, Liberica (Barako), Excelsa and Robusta.[27] 90 percent of coffee produced in the country is Robusta. There has been efforts to revitalize the coffee industry.[28]Coconuts[]

Coconuts plays an important role in the national economy of the Philippines. According to figures published in December 2015 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, it is the world's largest producer of coconuts, producing 19,500,000 tonnes in 2015.[29] Production in the Philippines is generally concentrated in medium-sized farms.[30] There are 3.5 million hectares dedicated to coconut production in the Philippines, which accounts for 25 per cent of total agricultural land in the country.[31] In 1989, it was estimated that between 25 percent and 33 percent of the population was at least partly dependent on coconuts for their livelihood. Historically, the Southern Tagalog and Bicol regions of Luzon and the Eastern Visayas were the centers of coconut production.[32] In the 1980s, Western Mindanao and Southern Mindanao also became important coconut-growing regions.[32]

Fruits[]

The Philippines is the world's third largest producer of pineapples, producing more than 2.4 million of tonnes in 2015.[33] The Philippines was in the top three banana producing countries in 2010, including India and China.[34] Davao and Mindanao contribute heavily to the total national banana crop.[34] Mangoes are the third most important fruit crop of the country based on export volume and value next to bananas and pineapples.[35]

Sugar[]

There are at least 19 provinces and 11 regions that produce sugarcane in the Philippines. A range from 360,000 to 390,000 hectares are devoted to sugarcane production. The largest sugarcane areas are found in the Negros Island Region, which accounts for 51% of sugarcane areas planted. This is followed by Mindanao which accounts for 20%; Luzon by 17%; Panay by 07%; and Eastern Visayas by 04%.[36] It is estimated that as of 2012, the industry provides direct employment to 700,000 sugarcane workers spread across 19 sugar producing provinces.[37]

Sugar growing in the Philippines pre-dates colonial Spanish contact.[38] Sugar became the most important agricultural export of the Philippines between the late eighteenth century and the mid-1970s.[38] During the 1950s and 60s, more than 20 percent income of Philippine exports came from the sugar industry.[38] Between 1913 and 1974, the Philippines sugar industry enjoyed favoured terms of trade with the US, with special access to the protected and subsidized the American sugar market.[38]

Animal agriculture[]

Crocodile[]

Crocodile farming in the Philippines refers to agricultural industries involving the raising and harvesting of crocodiles for the commercial production of crocodile meat and crocodile leather.

In the Philippines, crocodile farmers breed and raise two species of Philippine crocodiles: the Philippine saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus)[39] and the Philippine freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis). Farms that trade crocodile skin are regulated by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).[39][40]

Crocodiles help maintain the balance of Philippine ecosystems such as wetlands; crocodile farming in the Philippines is also geared towards the rescue and conservation of both C. porosus and the "endangered and endemic" C. mindorensis. Crocodile farms also contribute to tourism in the Philippines and offer public education about crocodiles.[39][40]Ostrich[]

Other crops[]

Abaca[]

According to the Philippine Fiber Industry Development Authority, the Philippines provided 87.4% of the world's abaca in 2014, earning the Philippines US$111.33 million.[43] The demand is still greater than the supply.[43] The remainder came from Ecuador (12.5%) and Costa Rica (0.1%).[43] The Bicol region in the Philippines produced 27,885 metric tons of abaca in 2014, the largest of any Philippine region.[43] The Philippine Rural Development Program (PRDP) and the Department of Agriculture reported that in 2009-2013, Bicol Region had 39% share of Philippine abaca production while overwhelming 92% comes from Catanduanes Island. Eastern Visayas, the second largest producer had 24% and the Davao Region, the third largest producer had 11% of the total production. Around 42 percent of the total abaca fiber shipments from the Philippines went to the United Kingdom in 2014, making it the top importer.[43] Germany imported 37.1 percent abaca pulp from the Philippines, importing around 7,755 metric tons (MT).[43] Sales of abaca cordage surged 20 percent in 2014 to a total of 5,093 MT from 4,240 MT, with the United States holding around 68 percent of the market.[43]

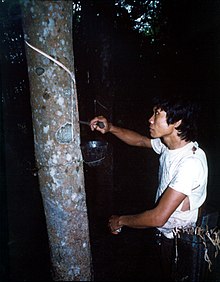

Rubber[]

There are an estimated 458,000 families dependent upon the cultivation of rubber trees. Rubber is mainly planted in Mindanao, with some plantings in Luzon and the Visayas.[44] As of 2013, the total rubber production is 111,204 tons.[45]

Government[]

The Food and Agriculture Organization described local policy measures as some of the most proactive in risk reduction.[3] Among those policies is support for genetically modified crops.[22]

Department of agriculture[]

The Department of Agriculture (abbreviated as DA; Filipino: Kagawaran ng Agrikultura), is the executive department of the Philippine government responsible for the promotion of agricultural and fisheries development and growth.[46] It has its headquarters at Elliptical Road corner Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City.

Land reform[]

Environmental issues[]

Deforestation[]

Some agricultural practices, including export crops and encroachment by small farmers, lead to deforestation.[47]

Climate change[]

Agriculture is one of the Philippines’ largest sectors and will continue to be adversely impacted by the effects of climate change. The agriculture sector employs 35% of the working population and generated 13% of the country's GDP in 2009.[48] The two most important crops, rice and corn, account for 67% of the land under cultivation and stand to see reduced yields from heat and water stress.[48] Rice, wheat, and corn crops are expected to see a 10% decrease in yield for every 1°C increase over a 30°C average annual temperature.[49]

Increases in extreme weather events will have devastating affects on agriculture. Typhoons (high winds) and heavy rainfall contribute to the destruction of crops, reduced soil fertility, altered agricultural productivity through severe flooding, increased runoff, and soil erosion.[49] Droughts and reduced rainfall leads to increased pest infestations that damage crops as well as an increased need for irrigation.[49] Rising sea levels increases salinity which leads to a loss of arable land and irrigation water.[49]

All of these factors contribute to higher prices of food and an increased demand for imports, which hurts the general economy as well as individual livelihoods.[49] From 2006 to 2013, the Philippines experienced a total of 75 disasters that cost the agricultural sector $3.8 billion in loss and damages.[49] Typhoon Haiyan alone cost the Philippines' agricultural sector an estimated US$724 million after causing 1.1 million tonnes of crop loss and destroying 600,000 ha of farmland.[50] The agricultural sector is expected to see an estimated annual GDP loss of 2.2% by 2100 due to climate impacts on agriculture.[49]See also[]

- Federation of Free Farmers

- Land Bank of the Philippines

References[]

- ^ http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS?locations=PH

- ^ "Philippines at a glance | FAO in the Philippines | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Philippines at a glance | FAO in the Philippines | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Diamond, J. (2003-04-25). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734.

- ^ Donohue, Mark; Denham, Tim (2010). "Farming and Language in Island Southeast Asia: Reframing Austronesian History". Current Anthropology. 51 (2): 223–256. doi:10.1086/650991. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 10.1086/650991. S2CID 4815693.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (2006), "Asian Farming Diasporas? Agriculture, Languages, and Genes in China and Southeast Asia", Archaeology of Asia, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 96–118, doi:10.1002/9780470774670.ch6, ISBN 978-0-470-77467-0

- ^ Denham, Tim (August 2012). "Early farming in Island Southeast Asia: an alternative hypothesis". Antiquity: 250–257.

- ^ Eusebio, Michelle S.; Ceron, Jasminda R.; Acabado, Stephen B.; Krigbaum, John (2015). "Rice Pots or Not? Exploring Ancient lfugao Foodways through Organic Residue Analysis and Paleoethnobotany" (PDF). National Museum Journal of Cultural Heritage. 1: 11–20.

- ^ Snow, Bryan E.; Shutler, Richard; Nelson, D.E.; Vogel, J.S.; Southon, J.R. (1986). "Evidence of Early Rice Cultivation in the Philippines". Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. 14 (1): 3–11. ISSN 0115-0243. JSTOR 29791874.

- ^ Marci, Mia (2019-06-21). "Why do Filipinos like to eat rice?". Pepper. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Philippine Association of Agriculturists. "ANNOUNCEMENT: All Licensed Agriculturists Required to Submit a COGS to Renew their License". Philippine Association of Agriculturists.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "IRR of PRC Resolution No. 2000-663 (Resolution Creating the Board of Agriculture)" (PDF). Professional Regulation Commission. Board of Agriculturists. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "RESULTS: November 2019 Agriculturists Licensure Examination". Rappler. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Agriculture | Professional Regulation Commission". www.prc.gov.ph. Retrieved 2021-04-30.

- ^ "Republic Act 8435, Agricultural and Fisheries Modernization Act of 1997.pdf" (PDF). Professional Regulation Commission. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Professional Regulations Commission. "PRC Resolution No. 2000-663, Series of 2000" (PDF). Professional Regulations Commission.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "2009 Crop Production Statistics". FAO Stat. FAO Statistics. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "Factbox - Top 10 rice exporting, importing countries". Reuters. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "Palay: Volume of Production by Cereal Type, Geolocation, Period and Year". CountrySTAT Database. Bureau of Agricultural Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "Philippine economy posts 7.1 percent GDP growth". National Accounts of the Philippines. National Statistical Coordination Board. Archived from the original on 2011-04-15. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Authority, Philippine Statistics. "Self-Sufficiency Ratio of Selected Agricultural Commodities". countrystat.psa.gov.ph. Archived from the original on 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Freedman, Amy (2013). "Rice security in Southeast Asia: beggar thy neighbor or cooperation?". The Pacific Review. Taylor & Francis. 26 (5): 433–454. doi:10.1080/09512748.2013.842303. ISSN 0951-2748. p. 443

- ^ "Philippine Statistics Authority: CountrySTAT Philippines". Archived from the original on 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ ""Agri-Pinoy Corn Program", Republic of Philippines Department of Agriculture". da.gov.ph. Archived from the original on 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- ^ Peace and Equity Foundation. A primer on PEF’s Priority Commodities: an Industry Study on Cacao. Philippines, 2016. 2. Accessed June 26, 2017.

- ^ Flores, Wilson Lee (13 January 2014). "How can the Philippines be a top coffee exporter again?". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ "Coffee's Rich History in the Philippines". Philippine Coffee Board. Philippine Coffee Board. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Imbong, Peter (18 December 2014). "Philippines tries to reignite production". Nikkei Inc. Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^

Food And Agriculture Organization of the United Nations:

Economic And Social Department: The Statistical Division Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Hayami, Yūjirō; Quisumbing, Maria Agnes R.; Adriano, Lourdes S. (1990). Toward an alternative land reform paradigm: a Philippine perspective. Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-971-11-3096-1. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ^ "Philippines to launch coconut cluster". Investvine.com. 2013-02-16. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ronald E. Dolan, ed. Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- ^ fao.org. "Food and Agricultural commodities production > Countries by commodity > Pineapples (2013)". Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "banana". Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "mango". Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Master Plan For the Philippine Sugar Industry. Sugar Master Plan Foundation, Inc. 2010. p. 7.

- ^ Master Plan For the Philippine Sugar Industry. Sugar Master Plan Foundation, Inc. 2010. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "History". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Crocodiles in the Philippines". Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Regalado, Edith (July 5, 2013). "Louis Vuitton buying Phl croc skins". The Philippine Star

- ^ "About us, Philippine Ostrich & Crocodile Farms, Inc. PIONEERING THE OSTRICH INDUSTRY IN THE PHILIPPINES". Philippine Ostrich & Crocodile Farms, Inc. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Philippine Ostrich & Crocodile Farm". Municipality of Opol (08 October 2013). Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "PH biggest abaca exporter | Malaya Business Insight". Malaya Business Insight. June 15, 2015. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ "rubber". Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Food and Agricultural commodities production / Countries by commodity". Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "Department of Agriculture – Mandate, Mission and Vision". Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "Averting an agricultural and ecological crisis in the Philippines' salad bowl". Mongabay Environmental News. 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crost, Benjamin; Duquennois, Claire; Felter, Joseph H.; Rees, Daniel I. (March 2018). "Climate change, agricultural production and civil conflict: Evidence from the Philippines". Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 88: 379–395. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2018.01.005. hdl:10419/110685. S2CID 54078284.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g USAID (February 2017). "CLIMATE CHANGE RISK IN THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTRY FACT SHEET" (PDF). USAID.

- ^ Chandra, Alvin; McNamara, Karen E.; Dargusch, Paul; Caspe, Ana Maria; Dalabajan, Dante (February 2017). "Gendered vulnerabilities of smallholder farmers to climate change in conflict-prone areas: A case study from Mindanao, Philippines". Journal of Rural Studies. 50: 45–59. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.011.

Further reading[]

- Jesus, Ed. C. De (1980). The Tobacco Monopoly in the Philippines: Bureaucratic Enterprise and Social Change, 1766-1880. Ateneo University Press. ISBN 9715501680. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links[]

- Agriculture in the Philippines