Restricted Boltzmann machine

| Part of a series on |

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

A restricted Boltzmann machine (RBM) is a generative stochastic artificial neural network that can learn a probability distribution over its set of inputs.

RBMs were initially invented under the name Harmonium by Paul Smolensky in 1986,[1] and rose to prominence after Geoffrey Hinton and collaborators invented fast learning algorithms for them in the mid-2000. RBMs have found applications in dimensionality reduction,[2] classification,[3] collaborative filtering,[4] feature learning,[5] topic modelling[6] and even many body quantum mechanics.[7][8] They can be trained in either supervised or unsupervised ways, depending on the task.

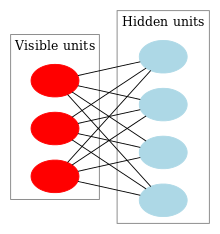

As their name implies, RBMs are a variant of Boltzmann machines, with the restriction that their neurons must form a bipartite graph: a pair of nodes from each of the two groups of units (commonly referred to as the "visible" and "hidden" units respectively) may have a symmetric connection between them; and there are no connections between nodes within a group. By contrast, "unrestricted" Boltzmann machines may have connections between hidden units. This restriction allows for more efficient training algorithms than are available for the general class of Boltzmann machines, in particular the gradient-based contrastive divergence algorithm.[9]

Restricted Boltzmann machines can also be used in deep learning networks. In particular, deep belief networks can be formed by "stacking" RBMs and optionally fine-tuning the resulting deep network with gradient descent and backpropagation.[10]

Structure[]

The standard type of RBM has binary-valued (Boolean) hidden and visible units, and consists of a matrix of weights of size . Each weight element of the matrix is associated with the connection between the visible (input) unit and the hidden unit . In addition, there are bias weights (offsets) for and for . Given the weights and biases, the energy of a configuration (pair of boolean vectors) (v,h) is defined as

or, in matrix notation,

This energy function is analogous to that of a Hopfield network. As with general Boltzmann machines, the joint probability distribution for the visible and hidden vectors is defined in terms of the energy function as follows,[11]

where is a partition function defined as the sum of over all possible configurations, which can be interpreted as a normalizing constant to ensure that the probabilities sum to 1. The marginal probability of a visible vector is the sum of over all possible hidden layer configurations,[11]

- ,

and vice versa. Since the underlying graph structure of the RBM is bipartite (meaning there is no intra-layer connections), the hidden unit activations are mutually independent given the visible unit activations. Conversely, the visible unit activations are mutually independent given the hidden unit activations.[9] That is, for m visible units and n hidden units, the conditional probability of a configuration of the visible units v, given a configuration of the hidden units h, is

- .

Conversely, the conditional probability of h given v is

- .

The individual activation probabilities are given by

- and

where denotes the logistic sigmoid.

The visible units of Restricted Boltzmann Machine can be multinomial, although the hidden units are Bernoulli.[clarification needed] In this case, the logistic function for visible units is replaced by the softmax function

where K is the number of discrete values that the visible values have. They are applied in topic modeling,[6] and recommender systems.[4]

Relation to other models[]

Restricted Boltzmann machines are a special case of Boltzmann machines and Markov random fields.[12][13] Their graphical model corresponds to that of factor analysis.[14]

Training algorithm[]

Restricted Boltzmann machines are trained to maximize the product of probabilities assigned to some training set (a matrix, each row of which is treated as a visible vector ),

or equivalently, to maximize the expected log probability of a training sample selected randomly from :[12][13]

The algorithm most often used to train RBMs, that is, to optimize the weight vector , is the contrastive divergence (CD) algorithm due to Hinton, originally developed to train PoE (product of experts) models.[15][16] The algorithm performs Gibbs sampling and is used inside a gradient descent procedure (similar to the way backpropagation is used inside such a procedure when training feedforward neural nets) to compute weight update.

The basic, single-step contrastive divergence (CD-1) procedure for a single sample can be summarized as follows:

- Take a training sample v, compute the probabilities of the hidden units and sample a hidden activation vector h from this probability distribution.

- Compute the outer product of v and h and call this the positive gradient.

- From h, sample a reconstruction v' of the visible units, then resample the hidden activations h' from this. (Gibbs sampling step)

- Compute the outer product of v' and h' and call this the negative gradient.

- Let the update to the weight matrix be the positive gradient minus the negative gradient, times some learning rate: .

- Update the biases a and b analogously: , .

A Practical Guide to Training RBMs written by Hinton can be found on his homepage.[11]

Literature[]

- Fischer, Asja; Igel, Christian (2012), "An Introduction to Restricted Boltzmann Machines", Progress in Pattern Recognition, Image Analysis, Computer Vision, and Applications, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 14–36, retrieved 2021-09-19

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Smolensky, Paul (1986). "Chapter 6: Information Processing in Dynamical Systems: Foundations of Harmony Theory" (PDF). In Rumelhart, David E.; McLelland, James L. (eds.). Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Volume 1: Foundations. MIT Press. pp. 194–281. ISBN 0-262-68053-X.

- ^ Hinton, G. E.; Salakhutdinov, R. R. (2006). "Reducing the Dimensionality of Data with Neural Networks" (PDF). Science. 313 (5786): 504–507. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..504H. doi:10.1126/science.1127647. PMID 16873662. S2CID 1658773.

- ^ Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y. (2008). Classification using discriminative restricted Boltzmann machines (PDF). Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning - ICML '08. p. 536. doi:10.1145/1390156.1390224. ISBN 9781605582054.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Salakhutdinov, R.; Mnih, A.; Hinton, G. (2007). Restricted Boltzmann machines for collaborative filtering. Proceedings of the 24th international conference on Machine learning - ICML '07. p. 791. doi:10.1145/1273496.1273596. ISBN 9781595937933.

- ^ Coates, Adam; Lee, Honglak; Ng, Andrew Y. (2011). An analysis of single-layer networks in unsupervised feature learning (PDF). International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ruslan Salakhutdinov and Geoffrey Hinton (2010). Replicated softmax: an undirected topic model. Neural Information Processing Systems 23.

- ^ Carleo, Giuseppe; Troyer, Matthias (2017-02-10). "Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks". Science. 355 (6325): 602–606. arXiv:1606.02318. Bibcode:2017Sci...355..602C. doi:10.1126/science.aag2302. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28183973. S2CID 206651104.

- ^ Melko, Roger G.; Carleo, Giuseppe; Carrasquilla, Juan; Cirac, J. Ignacio (September 2019). "Restricted Boltzmann machines in quantum physics". Nature Physics. 15 (9): 887–892. Bibcode:2019NatPh..15..887M. doi:10.1038/s41567-019-0545-1. ISSN 1745-2481.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miguel Á. Carreira-Perpiñán and Geoffrey Hinton (2005). On contrastive divergence learning. Artificial Intelligence and Statistics.

- ^ Hinton, G. (2009). "Deep belief networks". Scholarpedia. 4 (5): 5947. Bibcode:2009SchpJ...4.5947H. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.5947.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Geoffrey Hinton (2010). A Practical Guide to Training Restricted Boltzmann Machines. UTML TR 2010–003, University of Toronto.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sutskever, Ilya; Tieleman, Tijmen (2010). "On the convergence properties of contrastive divergence" (PDF). Proc. 13th Int'l Conf. On AI and Statistics (AISTATS). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asja Fischer and Christian Igel. Training Restricted Boltzmann Machines: An Introduction Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Pattern Recognition 47, pp. 25-39, 2014

- ^ María Angélica Cueto; Jason Morton; Bernd Sturmfels (2010). "Geometry of the restricted Boltzmann machine". Algebraic Methods in Statistics and Probability. American Mathematical Society. 516. arXiv:0908.4425. Bibcode:2009arXiv0908.4425A.

- ^ Geoffrey Hinton (1999). Products of Experts. ICANN 1999.

- ^ Hinton, G. E. (2002). "Training Products of Experts by Minimizing Contrastive Divergence" (PDF). Neural Computation. 14 (8): 1771–1800. doi:10.1162/089976602760128018. PMID 12180402. S2CID 207596505.

External links[]

- Introduction to Restricted Boltzmann Machines. Edwin Chen's blog, July 18, 2011.

- "A Beginner's Guide to Restricted Boltzmann Machines". Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2018.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Deeplearning4j Documentation

- "Understanding RBMs". Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2014.. Deeplearning4j Documentation

- Python implementation of Bernoulli RBM and tutorial

- SimpleRBM is a very small RBM code (24kB) useful for you to learn about how RBMs learn and work.

- Artificial neural networks

- Stochastic models

- Supervised learning

- Unsupervised learning

![{\displaystyle \arg \max _{W}\mathbb {E} \left[\log P(v)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/15d7e252690209a35d218dfaa0502782bccf0cac)