Rioplatense Spanish

| Rioplatense Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Argentine-Uruguayan Spanish | |

| Español rioplatense (Español argentino-uruguayo) | |

| Pronunciation | [espaˈɲol ri.oplaˈtense] |

| Native to | Argentina, Uruguay |

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects | Outer Dialects: Norteño (Northern) Guaranítico (Northeastern) Cuyano (Northwestern) Cordobés (Central) Inner Dialects: Litoraleño (Coastal) Bonarense (Eastern) Patagónico (Southern) Uruguayan |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academia Argentina de Letras Academia Nacional de Letras de Uruguay |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-2 | spa[2] |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | es-AR |

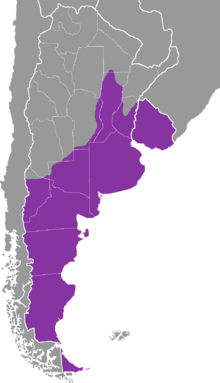

Spanish dialects in Argentina | |

Rioplatense Spanish (/ˌriːoʊpləˈtɛnseɪ/),[3] also known as Rioplatense Castilian, is a variety of Spanish[4][5][6] spoken mainly in and around the Río de la Plata Basin of Argentina and Uruguay.[7] It is also referred to as River Plate Spanish or Argentine Spanish.[8] Being the most prominent dialect to employ voseo in both speech and writing, many features of Rioplatense are also shared with the varieties spoken in south and eastern Bolivia, and Paraguay. This dialect is often spoken with an intonation resembling that of the Neapolitan language of Southern Italy, but there are exceptions. The word employed to name the Spanish language in Argentina is castellano (English: Castilian) and in Uruguay, español (English: Spanish). See names given to the Spanish language.

As Rioplatense is considered a dialect of Spanish and not a distinct language, there are no credible figures for a total number of speakers. The total population of these areas would amount to some 25–30 million, depending on the definition and expanse.

Location[]

Rioplatense is mainly based in the cities of Buenos Aires, Rosario, Santa Fe, La Plata, Mar del Plata and Bahía Blanca in Argentina, the most populated cities in the dialectal area, along with their respective suburbs and the areas in between, and in all of Uruguay. This regional form of Spanish is also found in other areas, not geographically close but culturally influenced by those population centers (e.g., in parts of Paraguay and in all of Patagonia). Rioplatense is the standard in audiovisual media in Argentina and Uruguay. To the north, and northeast exists the hybrid Riverense Portuñol.

Influences on the language[]

The Spanish brought their language to the area during the Spanish colonization in the region. Originally part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Río de la Plata basin had its status lifted to Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776.

Until the massive immigration to the region started in the 1870s, the language of the Río de la Plata had virtually no influence from other languages and varied mainly by localisms. Argentines and Uruguayans often state that their populations, like those of the United States and Canada, comprise people of relatively recent European descent, the largest immigrant groups coming from Italy and Spain.

European immigration[]

Several languages, especially Italian, influenced the criollo Spanish of the time, because of the diversity of settlers and immigrants to Argentina and Uruguay:

- 1870–1890: mainly Northern Italian, Spanish, Basque, Galician, Portuguese speakers and some from France, Germany, and other European countries.

- 1910–1945: again from Spain, Southern Italy, Portugal and in smaller numbers from across Europe; Jewish immigration—mainly from Russia and Poland from the 1910s until after World War II—was also significant.

- English speakers—from Britain and Ireland—were not as numerous, but were a substantial number as well.

Influence of indigenous populations in Argentina[]

European settlement decimated Native American populations before 1810, and also during the expansion into Patagonia (after 1870). However, the interaction between Spanish and several of the native languages has left visible traces. Words from Guarani, Quechua and others were incorporated into the local form of Spanish.

Some words of Amerindian origin commonly used in Rioplatense Spanish are:

- From Quechua: guacho or guacha (orig. wakcha "poor person, vagabond, orphan"); the term for the native cowboys of the Pampas, gaucho, may be related.

choclo/pochoclo (pop + choclo, from choqllo, corn) -- popcorn in Argentina

- From Guaraní: pororó—popcorn in Uruguay, Paraguay and some Argentine provinces.

- See Influences on the Spanish language for a more comprehensive review of borrowings into all dialects of Spanish.

Linguistic features[]

Phonology[]

Rioplatense Spanish distinguishes itself from other dialects of Spanish by the pronunciation of certain consonants.

| Labial | Dento-alvelar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | s | ʃ | (ʒ) | x | (h) | |||

| Lateral | l | ||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

- Like many other dialects, Rioplatense features yeísmo: the sounds represented by ll (historically the palatal lateral /ʎ/) and y (historically the palatal approximant /ʝ/) have fused into one. Thus, in Rioplatense, se cayó "he fell down" is homophonous with se calló "he became silent". This merged phoneme is generally pronounced as a postalveolar fricative, either voiced [ʒ] (as in English measure or the French j) in the central and western parts of the dialect region (this phenomenon is called zheísmo) or voiceless [ʃ] (as in English shine or the French ch), a phenomenon called sheísmo that originated in and around Buenos Aires[9] but has expanded to the rest of Argentina and Uruguay.[10][11]

- As in most American dialects, also, Rioplatense Spanish has seseo (/θ/ and /s/ are not distinguished). That is, casa ("house") is homophonous with caza ("hunt"). Seseo is common to other dialects of Spanish in Latin America, Canarian Spanish, Andalusian Spanish.

- In popular speech, the fricative /s/ has a very strong tendency to become 'aspirated' before another consonant (the resulting sound depending on what the consonant is, although stating it is a voiceless glottal fricative, [h], would give a clear idea of the mechanism) or simply in all syllable-final positions in less educated speech[citation needed]. This change may be realized only before consonants or also before vowels and, like lenition, is typically insensitive to word boundaries. That is, esto es lo mismo "this is the same" is pronounced something like [ˈehto ˈeɦ lo ˈmiɦmo], but in las águilas azules "the blue eagles", /s/ in las and águilas might remain [s] as no consonant follows: [las ˈaɣilas aˈsules], or become [h]: [lah ˈaɣilah aˈsuleh]; the pronunciation is largely an individual choice.

- The phoneme /x/ (written as ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩, and as ⟨j⟩ elsewhere) is never glottalized to [h] in the Atlantic coast.[citation needed] This phenomenon is common to other coastal dialects in Latin American Spanish, as well as Caribbean, Canarian, and Andalusian dialects, but not in Rioplatense dialect. Rioplatense speakers always realize it as [x], like people in Northern and Central Spain. Rioplatense speakers never realize it as [h] instead of [x], but [h] is a possible phonetic realization of /s/ when it is followed by two or more consonants or at the end of a phrase; it can be a free variation between [x] and [h].

- In some areas, speakers tend to drop the final /r/ sound in verb infinitives and the final /s/ in most words.[citation needed] This elision is considered a feature of uneducated speakers in some places, but it is widespread in others, at least in rapid speech.

Aspiration of /s/, together with loss of final /r/ and some common instances of diphthong simplification,[dubious ] tend to produce a noticeable simplification of the syllable structure, giving Rioplatense informal speech a distinct fluid consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel rhythm:[citation needed]

- Si querés irte, andate. Yo no te voy a parar.

- "If you want to go, then go. I'm not going to stop you."

[si keˈɾe ˈite ãnˈdate | ʃo no te βoi a paˈɾa] (help·info)

[si keˈɾe ˈite ãnˈdate | ʃo no te βoi a paˈɾa] (help·info)

Intonation[]

Preliminary research has shown that Rioplatense Spanish, and particularly the speech of the city of Buenos Aires, has intonation patterns that resemble those of Italian dialects. This correlates well with immigration patterns. Both Argentina and Uruguay have received large numbers of Italian settlers since the 19th century.

According to a study conducted by National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina[12] Buenos Aires and Rosario residents speak with an intonation most closely resembling Neapolitan. The researchers note this as a relatively recent phenomenon, starting in the beginning of the 20th century with the main wave of Southern Italian immigration. Before that, the porteño accent was more like that of Spain, especially Andalusia,[13] and in case of Uruguay, the accent was more like Canarian dialect.

Pronouns and verb conjugation[]

One of the features of the Argentine and Uruguayan speaking style is the voseo: the usage of the pronoun vos for the second person singular, instead of tú. In other Spanish-speaking regions where voseo is used, such as in Chile and Colombia, the use of voseo has at times been considered a nonstandard lower speaking style, whereas in Argentina and Uruguay it is standard.

The second person plural pronoun, which is vosotros in Spain, is replaced with ustedes in Rioplatense, as in most other Latin American dialects. While usted is the formal second person singular pronoun, its plural ustedes has a neutral connotation and can be used to address friends and acquaintances as well as in more formal occasions (see T-V distinction). Ustedes takes a grammatically third- person plural verb.

As an example, see the conjugation table for the verb amar (to love) in the present tense, indicative mode:

| Person/Number | Peninsular | Rioplatense |

|---|---|---|

| 1st sing. | yo amo | yo amo |

| 2nd sing. | tú amas | vos amás |

| 3rd sing. | él ama | él ama |

| 1st plural | nosotros amamos | nosotros amamos |

| 2nd plural | vosotros amáis | ustedes aman¹ |

| 3rd plural | ellos aman | ellos aman |

- (¹) Ustedes is used throughout most of Latin America for both the familiar and formal. In Spain, outside of Andalusia, it is used only in formal speech for the second person plural.

Although apparently there is just a stress shift (from amas to amás), the origin of such a stress is the loss of the diphthong of the ancient vos inflection from vos amáis to vos amás. This can be better seen with the verb "to be": from vos sois to vos sos. In vowel-alternating verbs like perder and morir, the stress shift also triggers a change of the vowel in the root:

| Peninsular | Rioplatense |

|---|---|

| yo pierdo | yo pierdo |

| tú pierdes | vos perdés |

| él pierde | él pierde |

| nosotros perdemos | nosotros perdemos |

| vosotros perdéis | ustedes pierden |

| ellos pierden | ellos pierden |

For the -ir verbs, the Peninsular vosotros forms end in -ís, so there is no diphthong to simplify, and Rioplatense vos employs the same form: instead of tú vives, vos vivís; instead of tú vienes, vos venís (note the alternation).

| Verb | Standard Spanish | Castilian in plural | Rioplatense | Chilean | Maracaibo Voseo | English (US/UK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantar | tú cantas | vosotros cantáis | vos cantás | tú cantái | vos cantáis | you sing |

| Correr | tú corres | vosotros corréis | vos corrés | tú corrí | vos corréis | you run |

| Partir | tú partes | vosotros partís | vos partís | tú partí | vos partís | you leave |

| Decir | tú dices | vosotros decís | vos decís | tú decí | vos decís | you say |

The imperative forms for vos are identical to the imperative forms in Peninsular but stressing the last syllable:

- Hablá más fuerte, por favor. "Speak louder, please." (habla in Peninsular)

- Comé un poco de torta. "Eat some cake." (come in Peninsular)

When in Peninsular the imperative has one syllable, a vowel corresponding to the verb's class is added (stress remains the same):

- Vení para acá. "Come over here." (ven in Peninsular)

- Hacé lo que te dije. "Do what I told you" (haz in Peninsular)

Exceptions

- Decime dónde está. "Tell me where it is" (Dime in Peninsular) the second syllable is stressed

The verb ir (to go) is never used in this form. The corresponding form of the verb andar (to walk, to go) substitutes for it.

- Andá para allá. "Go there" (ve in Peninsular)

The plural imperative uses the ustedes form (i. e. the third person plural subjunctive, as corresponding to ellos).

As for the subjunctive forms of vos verbs, while they tend to take the tú conjugation, some speakers do use the classical vos conjugation, employing the vosotros form minus the i in the final diphthong. Many consider only the tú subjunctive forms to be correct.

- Espero que veas or Espero que veás "I hope you can see" (Peninsular veáis)

- Lo que quieras or (less used) Lo que quierás/querás "Whatever you want" (Peninsular queráis)

In the preterite, an s is sometimes added, for instance (vos) perdistes. This corresponds to the classical vos conjugation found in literature. Compare Iberian Spanish form vosotros perdisteis.

Other verb forms coincide with tú after the i is omitted (the vos forms are the same as tú).

- Si salieras "If you went out" (Peninsular salierais)

| Standard Spanish | Rioplatense / other Argentine | Chilean | Maracaibo Voseo | Castilian in plural | English (US/UK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lo que quieras | lo que quieras/quierás | lo que querái | lo que queráis | whatever you want | |

| espero que veas | espero que veas/veás | espero que veái | espero que veáis | I hope you can see | |

| no lo toques | no lo toqués | no lo toquís | no lo toquéis | don't touch it | |

| si salieras | si salierai | si salierais | if you went out | ||

| si amaras | si amarai | si amarais | if you loved | ||

| vivías | vivíai | vivíais | you lived | ||

| cantabas | cantabai | cantabais | you sang | ||

| dirías | diríai | diríais | you'd say | ||

| harías | haríai | haríais | you'd do | ||

Usage[]

In the old times, vos was used as a respectful term. In Rioplatense, as in most other dialects which employ voseo, this pronoun has become informal, supplanting the use of tú (compare you in English, which used to be formal singular but has replaced and obliterated the former informal singular pronoun thou). It is used especially for addressing friends and family members (regardless of age), but may also include most acquaintances, such as co-workers, friends of one's friends, etc.

Usage of tenses[]

Although literary works use the full spectrum of verb inflections, in Rioplatense (as well as many other Spanish dialects), the future tense tends to use a verbal phrase (periphrasis) in the informal language.

This verb phrase is formed by the verb ir ("to go") followed by the preposition a ("to") and the main verb in the infinitive. This resembles the English phrase to be going to + infinitive verb. For example:

- Creo que descansaré un poco → Creo que voy a descansar un poco (I think I will rest a little → I think I am going to rest a little)

- Mañana me visitará mi madre → Mañana me va a visitar mi vieja (Tomorrow my mother will visit me → Tomorrow my mother is going to visit me)

- La visitaré mañana → La voy a visitar mañana (I will visit her tomorrow → I am going to visit her tomorrow)

The present perfect (Spanish: Pretérito perfecto compuesto), just like pretérito anterior, is rarely used: the simple past replaces it. However, the Present Perfect is still used in Northwestern Argentina, particularly in the province of Tucumán.

- Juan no ha llegado todavía → Juan no llegó todavía (Juan has not arrived yet → Juan did not arrive yet)

- El torneo ha comenzado → El torneo empezó (The tournament has begun → The tournament began)

- Ellas no han votado → Ellas no votaron (They have not voted → They did not vote)

But, in the subjunctive mood, the present perfect is still widely used:

- No creo que lo hayan visto ya (I don't believe they have already seen him)

- Espero que lo hayas hecho ayer (I hope you did it yesterday)

In Buenos Aires a reflexive form of verbs is often used - "se viene" instead of "viene'', etc.

Influence beyond Argentina[]

In Chilean Spanish there is plenty of lexical influence from the Argentine dialects suggesting a possible "masked prestige"[14] otherwise not expressed, since the image of Argentine things is usually negative. Influences run across the different social strata of Chile. Argentine tourism in Chile during summer and Chilean tourism in Argentina would influence the speech of the upper class. The middle classes would have Argentine influences by watching football on cable television and by watching Argentine programs in the broadcast television. La Cuarta, a "popular" tabloid, regularly employs lunfardo words and expressions. Usually Chileans do not recognize the Argentine borrowings as such, claiming they are Chilean terms and expressions.[14] The relation between Argentine dialects and Chilean Spanish is one of "asymmetric permeability", with Chilean Spanish adopting sayings of the Argentine variants but usually not the other way around.[14] Despite this, people in Santiago, Chile, value Argentine Spanish poorly in terms of "correctness", far behind Peruvian Spanish, which is considered the most correct form.[15]

Some Argentinian words have been adopted in Iberian Spanish such as pibe, piba[16] "boy, girl", taken into Spanish slang where it produced pibón,[17] "very attractive person".

See also[]

- Diccionario de argentinismos (book)

- Immigration to Argentina

- Lunfardo, Buenos Aires slang argot

- Cocoliche, a pidgin of Italian and Spanish formerly spoken by Italians in Greater Buenos Aires.

- South American Spanish

- Spanish dialects and varieties

- Voseo

References[]

- ^ Spanish → Argentina & Uruguay at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- ^ "ISO 639-2 Language Code search". Library of Congress. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ [espaˈɲol ri.oplaˈtense] or [-ˈʒano -]

- ^ Orlando Alba, Zonificación dialectal del español en América ("Classification of the Spanish Language within Dialectal Zones in America"), in: César Hernández Alonso (ed.), "Historia presente del español de América", Pabecal: Junta de Castilla y León, 1992.

- ^ Jiří Černý, "Algunas observaciones sobre el español hablado en América" ("Some Observations about the Spanish Spoken in America"). Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucencis, Facultas Philosophica Philologica 74, pp. 39-48, 2002.

- ^ Alvar, Manuel, "Manual de dialectología hispánica. El español de América", ("Handbook of Hispanic Dialectology. Spanish Language in America."). Barcelona 1996.

- ^ Resnick, Melvyn: Phonological Variants and Dialects Identification in Latin American Spanish. The Hague 1975.

- ^ Del Valle, José, ed. (2013). A Political History of Spanish: The Making of a Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–228. ISBN 9781107005730.

- ^ Charles B. Chang, "Variation in palatal production in Buenos Aires Spanish". Selected Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics, ed. Maurice Westmoreland and Juan Antonio Thomas, 54-63. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, 2008.

- ^ Staggs, Cecelia (2019). "A Perception Study of Rioplatense Spanish". McNair Scholars Research Journal. Boise State University. 14 (1).

Many studies have shown that within the last 70 to 80 years, there has been a strong transition towards the voiceless [ʃ] in both Argentina and Uruguay, with Argentina having completed the change by 2004 and Uruguay following only recently [...]

- ^ Díaz-Campos, Manuel (2014). Introducción a la sociolinguistica hispana. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ Colantoni, Laura; Gurlekian, Jorge (August 2004). "Convergence and intonation: historical evidence from Buenos Aires Spanish". Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. Cambridge University press. 7 (2): 107–119. doi:10.1017/S1366728904001488. ISSN 1366-7289. S2CID 56111230.

- ^ "Napolitanos y porteños, unidos por el acento - 06.12.2005 - lanacion.com". Lanacion.com.ar. 2005-12-06. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Salamanca, Gastón; Ramírez, Ariella (2014). "Argentinismos en el léxico del español de Chile: Nuevas evidencias". Atenea. 509: 97–121. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Rojas, Darío (2014). "Actitudes lingüísticas en Santiago de Chile". In En Chiquito, Ana Beatriz; Quezada Pacheco, Miguel Ángel (eds.). Actitudes lingüísticas de los hispanohablantes hacia el idioma español y sus variantes. Bergen Language and Linguistic Studies (in Spanish). 5. doi:10.15845/bells.v5i0.679.

- ^ pibe, piba | Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (23.3 electronic ed.). Real Academia Española - ASALE. 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Diccionario de la lengua española | Edición del Tricentenario (in Spanish) (23.3 electronic ed.). Real Academia Española - ASALE. 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

Further reading[]

- Bongiovanni, Silvina (2019), "An acoustical analysis of the merger of /ɲ/ and /nj/ in Buenos Aires Spanish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, doi:10.1017/S0025100318000440

- Coloma, Germán (2018), "Argentine Spanish" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 48 (2): 243–250, doi:10.1017/S0025100317000275, S2CID 232345835

External links[]

- (in Spanish) Diccionario argentino-español

- Jergas de habla hispana Spanish dictionary specializing in slang and colloquial expressions, featuring all Spanish-speaking countries, including Argentina and Uruguay.

- Example of a rare realización of ll as [z] in a song by the singer Daniel Magal

- Spanish dialects of South America

- Languages of Argentina

- Languages of Uruguay

- Italian-Argentine culture

- Italian-Uruguayan culture