Russo-Circassian War

| Russo-Circassian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Caucasian War | |||||||||

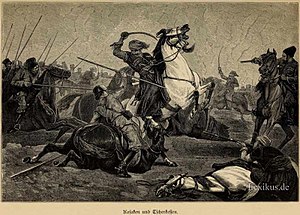

Circassian and Russian forces in combat | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

show

Diplomatic support: |

show

Diplomatic and equipment support: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

…and others |

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 150,000[20]–300,000[21] regulars | 20,000[22]–60,000[23] regulars | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| During the Circassian Genocide, about 1,500,000[35][36][37][38][39] indigenous highland Caucasians were expelled mainly to the Ottoman Empire, and a much smaller number to Persia. An unknown number of those expelled died during deportation.[40] | |||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Circassians |

|---|

|

| Circassian diaspora by region or country |

| Circassian Tribes |

|

Surviving Destroyed or barely alive |

| Religion in Circassia |

|

| Languages and dialects |

|

| History |

|

Ancient Medieval

Contemporary

Key battles |

| Culture |

|

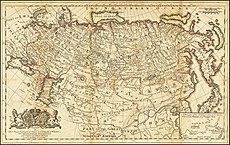

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

Prehistory • Antiquity • Early Slavs

Feudal Rus' (1097–1547) Mongol conquest • Vladimir-Suzdal Grand Duchy of Moscow • Novgorod Republic

Russian Revolution (1917–1923) February Revolution • Provisional Government

|

||||||||||||||

|

Timeline 860–1721 • 1721–1796 • 1796–18551855–1892 • 1892–1917 • 1917–1927 1927–1953 • 1953–1964 • 1964–1982 1982–1991 • 1991–present |

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

The Russo-Circassian War (Adyghe: Урыс-адыгэ зауэ, romanized: Wurıs-adığə zawə; Russian: Русско-черкесская война; 1763–1864; also known as the Russian Invasion of Circassia) was the military conflict between Circassia and Russia,[41] starting in 1763 with the Russian Empire's attempts to establish forts in Circassia and quickly annex the region, followed by the Circassian refusal of the annexation;[42] ending 101 years later with the last army of Circassia defeated on May 21, 1864, making it exhausting and casualty heavy for both sides as well as being the longest war Russia ever waged in history.[43] The end of the war saw the Circassian genocide take place[I] in which Imperial Russia aimed to systematically destroy the Circassian people[49][50][51] where several attroticies were committed by the Russian forces[52][53] and up to 1,500,000 Circassians (95-97% of the total population) were either killed or expelled to the Ottoman Empire (especially in modern-day Turkey; see Circassians in Turkey), creating the Circassian diaspora.[41]

While the Russo-Circassian War began as an isolated conflict, Russian expansion through the entire region soon brought it into conflict with a number of other nations in the Caucasus, in what later became known as the Caucasian War, of which the Russo-Circassian War became a part. Both came to an end with the total occupation of the region by Russian forces.

Summary[]

General info[]

Early relations between Russians and Circassians[]

The earliest recorded hostilities between Russia and the Circassians began in 985 when Russian forces under Prince Sviatoslav, raided the region. Following the invasion under Prince Sviatoslav, hostilities again broke out in 1022, when Prince Mstislav of Tamatarkha occupied the region.[54]

In the 1550s, Prince Temruk of Eastern Circassia allied the Russian Tsar Ivan IV and built a defense against possible enemies. Circassians were Christians during this period and Islam had not begun to spread.[55] In 1561, Ivan the Terrible married Goshan, daughter of the Kabardian prince, and named her Mariya. The Circassian-Russian allience was damaged and eventually broken when the Circassians converted to Islam and adopted a pro-Ottoman policy.

Political reasons of the war[]

Circassia was a key strategic location amidst the power struggle between the emerging Russian Empire, established England and France, and the failing Ottoman Empire. Russia set her sights on expansion along the Black Sea, and England sought to reduce Russia’s ability to take advantage of the declining Ottoman Empire, known as the Eastern Question.

To facilitate the fall of Persia, Russia would require shipyards on the Black Sea, which made Circassia, with its coastline, a target. Having taken that coastline, as well as Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, Russia hoped to cripple the Ottoman empire as well as the trading interests of Great Britain.

Starting date of the war[]

The date of the outbreak of the Russian-Circassian War is debated by historians.[54][56] While most scholars agree that conflicts have been going on since 1711, organised warfare happened only after 1763 when Russia established forts in Circassian territory.[9] Another view held by a smaller amount of scholars is that it began in 1817 with the arrival of Aleksey Yermolov, and prior to that it was merely clashes rather than an organised war.[9] This start date is the same as that of the larger Caucasian War.[57]

Failed attempts for a diplomatic solution[]

In 1764 Circassian knights Keysin Keytiqo and Kundeyt Shebez-Giray met with Catherine II in St. Petersburg. They informed Catherine II that "the military build-up in Mezdeug was unacceptable, the region has been a land of Circassians, the situation would create hostility and conflict". Catherine II refused diplomacy and the envoys were sent back. After this, the council convened and decided that war was inevitable, and refused Russian annexation.

In 1787, Circassian envoys, led by Tatarkhan Kurighoqo and Sidak Jankat, requested a meeting with the Russians to secure a peaceful solution, but they were denied. The Russians sent the envoys back, saying that the war would not stop and the Circassians were no longer free.[58]

In 1811, petitions were sent to St. Petersburg in Russia, appealing for the basic rights of Circassians in the occupied areas. They were ignored.

In 1837, some Circassian leaders offered the Russians a white peace, arguing that no more blood should be shed. In response to this offer, the Russian army under the command of General Yermolov burnt 36 Circassian villages and sent word, "We need the Circassian lands, not the Circassian people".[59]

In 1861, the Circassian Majlis held an emergency meeting, decided that continuing the war in vain would only result in more deaths and negotiated with the Russian Tsar Alexander II to establish peace, expressing their readiness to surrender completely, and accept Russian citizenship. However, the annexation of Circassia was not enough for Russia, the Tsarist government sought to evict the Circassians from the ethnic territory. The Tsar consistently continued the policy of his father, Nicholas I, and rejected the Circassian compromise proposals.[47] The Russian Tsar declared that Circassia will not only be annexed to Russia unconditionally, but the Circassians will be exiled, and if the Circassian people do not accept forcefully migrating, the Russian generals saw no problem in killing all Circassians. He gave the Circassian representatives a month to decide.[60] The Majlis did not accept leaving their lands and sent delegations to the Ottoman Empire and the United Kingdom to gain support from both countries, arguing that they are being massacred and they would be forced into exile soon.

British involvement[]

In 1836, the Russian navy captured an English merchant ship supplying ammunition to the Circassians. This merchant ship was part of an ongoing effort to bring supplies to the Circassians, supplies which also served to inspire more resistance.[61][62]

The conflict[]

Start of the war[]

On May 13, 1711, Tsar Peter I, ordered Araksin, Governor of Astrakhan, to pillage Circassia. Araksin moved with 30,000 strong Russian armed forces and, on August 26, 1711, broke into the lands of the Circassians, and captured Kopyl town (now Slavianski). From there, heading towards the Black Sea, he seized ports on the Kuban and looted and pillaged them. Then, he marched up along the Kuban River, pillaging villages.[63] During this single invasion in Circassia, the Russians killed 43, 247 Circassian men and women, and drove away 39,200 horses, 190,000 cattle, and 227,000 sheep from Circassia. Russia kept waging this type of warfare against Circassia during the period from 1716 to 1763, but this type of operations were not in order to annex Circassia, but rather raid it.

Although Peter I was unable to annex Circassia in his lifetime, he laid the political and ideological foundation for the occupation to take place. During the reign of Catherine II the Russian army was deployed and Russia started building forts in an attempt to quickly annex Circassia. As a result of this, battles were fought in 1763. While some Circassian nobles wanted to fight the Russians, arguing they could convince the Ottomans and Crimea to help them, other nobles wanted to avoid fighting with Russia and try to make peace. On August 21, 1765, the citizens of Circassia were instructed by Russian General De-Medem to accept Russian control or face the Russian army.[64]

Early battles[]

In 1769, the Russian army fought a battle against the Kabardian Circassians with the support of the Kalmyk Khan's 20,000 cavalrymen. A great battle took place in the Nartsane area in June 1769. Although neither side could gain the upper hand, Circassian forces under the leadership of Atajuq Bomet Misost inflicted huge losses on the Russian army. From about 1777 the Russians built a line of forts from Mozdok northwest to Azov. The presence of Cossacks in former grazing lands slowly converted traditional raiding from a kind of ritualized sport into a serious military struggle.

The Circassian region of Kabardia, near the Balka River, was attacked on September 29 1779 by the Russian forces, and occupied with the loss of the Kabardian defenders as well as 2,000 horses, 5,000 cattle, and 5,000 sheep.[65] The Russian army then raided the Abaza, Besleney, Chemguy and Hatuqwai regions in 1787, burning near a hundred villages.

Early attempts to unite Circassia[]

The Ottoman Empire had sent Ferah Ali Pasha at Anapa who tried to unite some of the tribes under Ottoman control. In 1791 the Natukhaj commoners peacefully took power from the aristocrats, declaring a republic.[66] A similar attempt among the Shapsugs led to a civil war which the commons won in 1803. Jaimoukha says that in 1770–1790 there was a class war among the Abadzeks that resulted in the extermination of the princes and the banishment of most of the nobility.[67] Henceforth the three west-central "democratic" tribes, Natukhaj, Shapsugs and Abedzeks, who formed the majority of the Circassians, managed their affairs through assemblies with only informal powers. This made things difficult for the Russians since there were no chiefs who might lead their followers into submission. Sefer Bey Zanuqo, the three Naibs of Shamil and the British adventurers all tried to organize the Circassians – with limited success.

Invasion of Eastern Circassia[]

Methods of terror[]

In 1800, as part of the Russian conquest of the Caucasus, Russia annexed eastern Georgia and by 1806 held Transcaucasia from the Black Sea to the Caspian. Russia had to hold the Georgian Military Highway in the center so the war against the mountaineers was divided into eastern and western parts. With Georgia out of the question, more armies were directed to Circassia. Russian armies crossed the Kuban River on March 1814. Circassia used this diplomatic opportunity to promote the young prince Jembulat Bolotoqo and sent a delegation to Ottomans, which complained against the Russian actions.[68][69][70]

Deciding that Circassians would not surrender at all, Russia began to destroy Circassian fortreses, villages and towns and slaughter the people.[71][72][36] General Aleksey Yermolov conclude that "terror" would be effective toward frontier protection instead of fortress construction as "moderation in the eyes of the barbarians is a sign of weakness".[36]

In 1804, the Kabardians and neighbouring Balkars, Karachays, Abazins, Ossetians, Ingushes, and Chechens, united in a military movement.[73] They demanded the destruction of the Kislovodsk Russian fort and of the Cordon line. This was one of three defensive lines, all of which consisted of chains of forts, which were built during the whole conflict: the Caucasian line in 1780, the Chernomorski Cord line in 1793, and the Sunja line in 1817. With the refusal of these demands, and despite threats of bloodshed from Georgian commander General Tsitsianov, the rebel forces began threatening the Kislovodsk fort.[74]

Russian forces commanded by General Glazenap were pushed back to Georgievsk and then put under siege, however the attacking Kabardian forces were eventually pushed back, and 80 Kabardian villages were burnt as a reprisal.[75]

In 1805, a major plague struck the north Caucasus and carried away a large part of the Kabardian population. Many argue that the plague was spread on purpose by Russia. Using this as an excuse, in 1810 about 200 villages were burned. In 1817 the frontier was pushed to the Sunzha River and in 1822 a line of forts was built from Vladikavkaz northwest through Nalchik to the Pyatigorsk area. After 1825 fighting subsided. Between 1805-1807, Bulgakov's army burned more than 280 villages.[76] The population of Kabarda, which was 350,000 in 1763, was only 37,000 in 1817.[77]

In May 1818, the village of Tram was surrounded, burnt, and its inhabitants killed by Russian forces under the command of General Delpotso, who took orders from Yermolov and who then wrote to the rebel forces: "This time, I am limiting myself on this. In the future, I will have no mercy for the guilty brigands; their villages will be destroyed, properties taken, wives and children will be slaughtered for us to watch in joy."[78] The Russians also constructed several more fortifications during that year. During the whole period from 1779 to 1818, 315,000 of the 350,000 Kabardinians had reportedly been killed by the Russian armies.[78]

These brutal methods annoyed the Circassians even more, and many Circassian princes, even princes who had been competing for centuries, joined hands to resist harder, many Russian armies were defeated, some completely destroyed. In Europe, especially in England, there was great sympathy for the Circassians who resisted the Russians.[79]

In response to persistent Circassian resistance and the failure of their previous policy of building forts, the Russian military began using a strategy of disproportionate retribution for raids. With the goal of imposing stability and authority beyond their current line of control and over the whole Caucasus, Russian troops retaliated by destroying villages or any place that resistance fighters were thought to hide, as well as employing assassinations and executions of whole families.[80]

Understanding that the resistance was reliant on being fed by sympathetic villages, the Russian military also systematically destroyed crops and livestock.[72] These tactics further enraged natives and intensified resistance to Russian rule. The Russians began to counter this by modifying the terrain, in both the environment and the demographics. They cleared forests by roads, destroyed native villages, and often settled new farming communities of Russians or pro-Russian Orthodox peoples. In this increasingly bloody situation, the complete destruction of the villages for Russian interests with everyone and everything within them became.a standard action by the Russian army and Cossack units.[81] Nevertheless, the Circassian resistance continued. Villages that had previously accepted Russian rule were found resisting again, much to the ire of Russian commanders.[82]

In September 1820, Russian forces began to forcibly resettle inhabitants of Eastern Circassia. Throughout the conflict, Russia had employed a tactic of divide and rule,[83] and following this, the Russians began to encourage the Karachay-Balkar and Ingush tribes, who had previously been subjugated by the Circassians, to rise up and join the Russian efforts.[84] Military forces were sent into Kabardia, killing cattle and causing large numbers of inhabitants to flee into the mountains, with the land these inhabitants had once lived on being acquired for the Kuban Cossacks. The entirety of Kabardia (Eastern Circassia) was then declared property of the Russian government.[85]

General Yermolov accelerated his efforts in Kabardia, with the month of March 1822 alone seeing fourteen villages being displaced as Yermolov led expeditions.[86] The construction of new defensive lines in Kabardia led to renewed uprisings, which were eventually crushed and the rebellious lords had their much needed peasant work forces freed by the Russian forces in order to discourage further uprisings. The area was placed under Russian military rule in 1822, as Kabardia eventually fully fell.

Invasion of Western Circassia[]

While Eastern Circassia was being occupied, Russia was also engaged in a war with the Turks (Russo-Turkish War of 1806–1812) in order to "free" the Black Sea from Turkish influence, and sporadic wars had also flared up with other neighbours. In western Circassia, which Russia had previously been merely foraying into, a number of tribes were dominant; the Besleneys, Abadzekhs, Ubykhs, Shapsughs, Hatuqwai and Natukhaj, portrayed by Russian propaganda as savages in a possible attempt to curry favour from the international community.[87] Russian and Circassian forces clashed repeatedly, particularly on the Kuban plains, where cavalry from both sides could manoeuvre freely.[88]

Trade with Circassia could not be prevented, however, and both the Turkish and the English supplied Circassia with firearms and ammunition with which to fight the Russians. England also supplied several advisors, while Turkey attempted to persuade Circassia to start a Holy War (Jihad), which would draw support from other nations.[89]

Rise of Jembulat Boletoqo[]

A Circassian commander, Jembulat Boletoqo, led an 800 strong cavalry force into Russian territory. Only one Cossack regiment decided to fight the rising Circassian army on 23 October at the village of Sabl on the Barsukly River. Jembulat's forces surrounded the Cossacks and killed all of them in a saber attack.[32][90]

In the summer of 1825, Russian forces carried out several military operations. On August 18, General Veliaminov burned the residency of Hajji Tlam, one of the elderly supporters of the Circassian resistance in Abadzekh, and killed his entire family. On January 31, Jembulat burned down the fortress of Marevskoye as revenge.[91][92] On 4 June 1828, Jembulat Boletoqo started his campaign into Russian lands with 2,000 cavalry under five flags of different Circassian principalities, as well as a Turkish flag as a symbol of their loyalty to Islam.

Political analyst Khan-Girei observed that the situation changed for Great-Prince Jembulat “after the field marshal Paskevich left the region”.[93] The new commander-in-chief, Baron Rosen, did not believe in human rights of the indigenous Circassians.[32][94]

Treaty of Adrianople[]

The Russians besieged Anapa in 1828. The Ottomans sought help from Circassians and the war lasted for two months. Anapa fell into the hands of the Russians. General Emanuel, commander of Russia's Caucasus armies, enraged, then razed 6 Natukhay villages and many Shapsugh villages. He then passed the Kuban and burned 210 more villages. Treaty of Adrianople (1829) was signed on 14 September 1829. According to this agreement, the Ottoman Empire was giving Circassia to Russia. Many, including German economist Karl Marx, criticised this event.

Circassians did not recognize the treaty. Circassian ambassadors were sent to England, France and Ottoman lands. The mission of the messengers was to tell about the savagery and destruction. In November 1830 the Natukhajs and Shapsugs sent a delegation to Turkey under Sefer Bey Zanuqo. The delegation returned with a few weapons and Sefer Bey remained in Istanbul. Before 1830 Russia basically maintained a siege line along the Kuban River. There was constant raiding by both sides but no change in borders. In the late 1830s Russia gained increasing control of the coast.

General Zass takes control[]

In 1833, Colonel Grigory Zass was appointed commander of a part of the Kuban Military Line with headquarters in the Batalpashinsk fortress. Colonel Zass received wide authority to act as he saw fit. He was a racist who considered Circassians to be an inferior race than Russians and other Europeans.[95][96][97][98][99][47] He thought the "European Race" was superior, particularly the Germans and Russians. The only way to deal with the Circassians, in his opinion, was to scare them away "just like wild animals."

Colonel Grigory Zass was a key figure in the Circassian genocide through ethnic cleansing, which included methods such as burning entire Circassian villages, deliberately causing epidemics, and entering villages and towns with the white flag and killing everyone.[100][101][102] He operated on all areas of Circassia, but East Circassia was effected the most. It is estimated 70% of the East Circassian population died in the process.[100][103]

In August 1833, Zass led his first expedition into Circassian territory, destroying as many villages and towns as possible. This was followed by a series of other expeditions. He attacked the Besleney region between November and December, destroying most villages, including the village of the double agent Aytech Qanoqo. He continued to exterminate the Circassian population between 1834 and 1835, particularly in the Abdzakh, Besleney, Shapsug, and Kabardian regions.

Zass' main strategy was to intercept and retain the initiative, terrorize the Circassians, and destroy Circassian settlements. After a victory, he would usually burn several villages and seize cattle and horses to show off, acts which he proudly admitted. He paid close attention to the enemy's morale. In his reports, he frequently boasted about the destruction of villages and glorified the mass murder of civilians.[104]

In October 1836, General Zass sent Jembulat Boletoqo word that he would like to make peace. This was a strategy, if Boletoqo came to the Russian fortress for explanation, he would be assassinated; in case he did not come, the Russians would claim that he was a warmonger.[105]

Prince Boletoqo came to Zass’ residency. The general was not there for his first visit, but Zass told him to come at an exact date when he would certainly be in his residency. On his way to the Prochnyi Okop fortress, Great Prince Jembulat was killed by a Russian sniper who was hiding in the forest on the Russian bank of the Kuban River at the intersection with the Urup River.[32]

In 1838, Zass spread false rumors about his serious illness, then staged his own death, weakening the Circassians' vigilance. On the same night, when the Circassians were celebrating their opressor's death, the suddenly "resurrected" Zass launched a raid that destroyed two villages.

[]

On April 13 1838, Russian forces engaged the Circassian army in the estuary of River Sochi, and on May 12 1838 the Russians landed at Tuapse with a naval invasion. The majority of engagements during this part of the conflict took place in the form of either amphibious landings on coastal towns in accordance with the directive laid out by the Tsar to secure possible ports, or by routing out Circassian forces entrenched in mountain strongholds. At Tuapse, the Russian landing had begun at 10:00 in the morning, and the Circassians were not beaten back from their positions until 5:00 in the afternoon, with the Russians suffering heavy casualties.[106][107] On the following day, May 13, when arriving to request permission to remove their dead from the battlefield, a few Circassians leaders were killed.[108][109]

In 1839, Russian forces landed at Subash and began construction of a fort, where they faced charges by Ubykh forces who were eventually driven back by shellfire from the Russian navy. Over 1000[110] soldiers then charged the Russian positions, however they were outflanked and overrun as they attempted to retreat. This pattern of attack by the Russian forces went on for several years.[111]

On February 7 1840, Circassian forces surrounded the Russian fort of Lazarev, stormed it and defeated the defenders. This victory was inspirational to them, and they went on to capture two more forts with an army of 11,000 men. With the Mikhailovski fortress ablaze and under the control of the Circassians, a Russian soldier who was hiding ran with a blazing torch into the ammunition cellar, destroying the fort in a suicide operation, killing all Circassians inside.

Circassian civil war[]

Imam Shamil wanted to unite Circassia under Islam, and sent three Sufi naibs for this mission.

The first Naib was Haji-Mohammad (1842–1844) who reached Circassia in May 1842. By October he was accepted as leader by the Shapsugs and some of the Natukhajs. Next February he moved south to Ubykh country but failed because he took sides in a civil conflict. By late 1843 he had the allegiance of the Natukhajs, Shapsugs and the Beslaneys and sent raiding parties as far as Stavropol. In the spring of 1844 he was defeated by the Russians, withdrew into the mountains and died there in May.

The second naib was Suleiman Effendi (1845) who arrived among the Abadzeks in February 1845. His main goal was to rise a Circassian force and to lead it back to Chechnya, but the Circassians did not want to lose their best fighters. After twice failing to lead his recruits through the Russian lines he surrendered and joined the Russians.

The third naib, Muhammad Amin (1849–1859), arrived in spring of 1849 and had much greater success. He assumed full control: established a standing army, started the manufacture of gunpowder, expanded cities and built the first jails. By mid-1851 he was greatly weakened but by the spring of 1853 he had regained control. However, Sefer Bey Zanuqo did not like him.

In 1853 Sefer Bey Zanuqo returned from Istanbul to Circassia. Zanuqo and Amin soon began to fight, the Natukhajs supporting Sefer Bey and the Abadzeks and Bzhedugs supporting Amin. When the allies asked Sefer Bey to turn over Anapa he replied that it was sovereign Circassian territory, thereby breaking with his protectors. When the Crimean War ended in 1856 Russia had a free hand in Circassia and the two leaders continued to fight both the Russians and each other. They agreed that the Porte should appoint a single leader; Amin went to Istanbul, but Sefer Bey stayed and worked against him. Amin returned, went again to Istanbul, was arrested at the request of the Russian ambassador, was sent to Syria, escaped and returned to Circassia by the end of 1857. On 20 November 1859, following the defeat of Shamil, Amin submitted. He stayed in Shapsug country for a while, then emigrated to Istanbul. Sefer Bey died in December of that year. His son Qarabatir took over.

Paris treaty of 1856[]

In the Paris treaty of 1856, British representative Earl of Clarendon insisted that Circassia remain an independent state, but French and Russian representatives wanted to give Circassian lands to Russia, while the Ottoman representatives were reportedly silent.[10][11][12] When Clarendon then tried to make the treaty state that Russia could not build forts in Circassia, he was again thwarted by the French representative. The final treaty also extended amnesty to nationals that had fought for enemy powers, but since Circassia had never previously been under Russian control, Circassians were exempt, and thus Circassians were now placed under de jure Russian sovereignty by the treaty, with Russia under no compulsion to grant Circassians the same rights as Russian citizens elsewhere.[10][11][12]

End of the war[]

In 1857, Dmitry Milyutin published the document in which he argued that the Circassian people should be destroyed.[112] According to Milyutin, the issue was not to take over the Circassian lands, but to put an end to the Circassians.[112][113][114] Rostislav Fadeyev supported the proposal, saying "It is not possible to tame the Circassians, if we destroy half of them completely, the other half will lay down their weapons".[36] By 1860 the Russians had seventy thousand soldiers in Circassia.

According to Ivan Drozdov, for the most part, the Russian army preferred to indiscriminately destroy areas where Circassians resided. In September 1862, after attacking a Circassian village and seeing some of its inhabitants flee into the forest, General Yevdokimov bombarded that forest for six hours straight and ordered his men to kill every living thing, he then set the forest on fire to make sure no survivors are left. Drozdov reported to have overheard Circassian men taking vows to sacrifice themselves to the cannons to allow their family and rest of their villages to escape, and later more reports of groups of Circassians doing so were received.

With the operation launched from the autumn of 1863, the Circassian villages and their supplies were to be burned, and this process was repeated until General Yevdokimov was convinced that all inhabitants of the region had died.

In May 1859, elders from the Bjedugh negotiated a peace with Russia and submitted to the Tsar. Other tribes soon submitted to the Russians, including the Abadzekhs on November 20 1859.[115]

The remaining Circassians established an assembly called Independence Majlis of Circassia (Adyghe: Шъхьафитныгъэ Хасэ, romanized: Şhafitnığə Xasə, lit. 'Majlis of Independence') in the capital city of Ş̂açə (Sochi) on 25 June 1861. Qerandiqo Berzeg was appointed as the head of the assembly. This assembly asked for help from Europe,[116] arguing that they would be forced into exile soon. However, before the result was achieved, Russian General Kolyobakin invaded Sochi and destroyed the parliament[117] and no country opposed this.[116]

A final battle took place in Qbaada in 1864. The battle took place between the Circassian army of 20,000 tribal horsemen and a Russian army of 100,000 men, consisting of Cossack and Russian horsemen, infantry and artillery. The Russian forces advanced from four sides. Circassian forces decided to not surrender to the Russian army, and tried to break the line, but many were hit by Russian artillery and infantry before they managed to reach the front. The remaining fighters continued to fight as militants, took down many units, and were soon defeated. All 20,000 Circassian horsemen died in the war. The Russian army began celebrating victory on the corpses of Circassian soldiers, and a military-religious parade was held, this was officially the end of the war. The place where this battle took place is known today as Krasnaya Polyana. "Krasnaya Polyana" meaning "red madow", takes its name from the Circassian blood flowing from the hill into the river. Circassian genocide was initiated after the Qbaada battle. The Russian army began raiding and burning Circassian villages, destroying fields to prevent return, cutting down trees, and driving the people to the Black Sea coast, the soldiers used many methods to entertain themselves. After 101 years of ressistance, all of Circassia fell into Russian hands. The only exception, the Hak'uch, who lived in the mountainous regions, despite being surrounded and unequipped, continued their resistance until the 1870s. In the end, Circassia was subjected to genocide and ethnic cleansing throughout, almost entirely.

Expulsion and genocide[]

The Circassian genocide was the Russian Empire's systematic mass murder,[118][37][38][39] ethnic cleansing,[119][37][38][39] forced migration,[120][37][38][39] and expulsion[121][37][38][39] of 800,000–1,500,000 Circassians[35][36][37][38][39] (at least 75% of the total population) from their homeland Circassia, which roughly encompassed the major part of the North Caucasus and the northeast shore of the Black Sea.[35]

After the war, Russian General Yevdokimov was tasked with forcing the surviving Circassian inhabitants to relocate outside of the region, primarily in the Ottoman Empire. This policy was enforced by mobile columns of Russian riflemen and Cossack cavalry, and Ottoman Empire archives show nearly 1.75 million migrants entering their land by 1879.[122] Other sources show that as many as 2 million Circassians were forced to flee in total.[123][124]

If Ottoman archives are correct, it would make it the largest civilian death toll of the 19th century,[125] and indeed, the Russian census of 1897 records only 150,000 Circassians, one tenth of the original number, still remaining in the now conquered region.[126][127]

90% of people with Circassian descent now live in other countries, primarily in Turkey, Jordan and other countries of the Middle East, with only 500,000–700,000 remaining in what is now Russia.[46] The depopulated Circassian lands were resettled by numerous ethnic groups, including Russians, Ukrainians and Georgians.[46]

See also[]

- Mission of the Vixen

- David Urquhart

Citations and notes[]

- ^ King, The Ghost of Freedom, p73-76. p74:"The hills, forests and uptown villages where highland horsemen were most at home were cleared, rearranged or destroyed... to shift the advantage to the regular army of the empire."... p75:"Into these spaces Russian settlers could be moved or "pacified" highlanders resettled."

- ^ "Kafkas Rus Savaşı". Cerkesyaorg (in Turkish). Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Gvosdev 2000, pp. 111–112.

- ^ (in Georgian) "გურიის სამთავრო" (Principality of Guria). In: ქართული საბჭოთა ენციკლოპედია (Encyclopaedia Georgiana). Vol. 3: p. 314-5. Tbilisi, 1978.

- ^ Шамхалы тарковские, ССКГ. 1868. Вып. 1. С. 58.

- ^ Lang, David Marshall (1962), A Modern History of Georgia, pp. 96-97. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Лайпанов Билал. (2001). "Ислам в истории и самосознании карачаевского народа". Ислам в Евразии. Москва: Прогресс-Традиция.

- ^ Svetlana Mikhaĭlovna Chervonnai︠a︡, Mikhail Nikolaevich Guboglo (1 January 1999). Все наши боги с нами и за нас: этническая идентичность и этническая мобилизация в современном искусстве народов России. T︠S︡IMO. ISBN 9785201137304.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ulrike (15 April 2014). Ethnic Belonging, Gender, and Cultural Practices: Youth Identities in Contemporary Russia. Columbia University Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9783838261522. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. Page 63

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baumgart. Peace of Paris. Pages 111– 112

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Conacher. Britain and the Crimea. pages 203, 215– 217.

- ^ Askerov, Ali (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Chechen Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 3.

- ^ Çirg, Ashad (1993). "Adıgelerin XIX. yüzyıldaki politik tarihinin incelenmesi gerekir". Kafkasya Gerçeği dergisi. 11: 61–62.

- ^ Polvinkina (2007). Çerkesya Gönül Yaram. Ankara. pp. 281–285.

- ^ Natho, Kadir. "The Russo-Circassian war".

- ^ Svetlana Mikhaĭlovna Chervonnai︠a︡, Mikhail Nikolaevich Guboglo (1 January 1999). Все наши боги с нами и за нас: этническая идентичность и этническая мобилизация в современном искусстве народов России. T︠S︡IMO. ISBN 9785201137304.

- ^ Berkok, Ismail Hakkı (1958). Tarihte Kafkasya. Istanbul.

- ^ Richmond 2008.

- ^ Mackie 1856:291

- ^ Jump up to: a b c J. F. B., The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus Cite error: The named reference "Baddeley" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). Cite error: The named reference "Baddeley" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Mackie 1856:292

- ^ A, M. Rus Çerkez Savaşı

- ^ Grigori F. Krivosheev Россия и СССР в войнах XX в. Потери вооружённых сил. Олма-Пресс, 2001.: Вооружённые конфликты на Северном Кавказе (1920—2000 гг.). p.568

- ^ "Private letter on the capture of Shamil (Russian)". 2 September 1859. Retrieved 31 December 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Hozhay, Dalhan (1998). Чеченцы в русско-кавказской войне [Chechens in the Russian-Caucasian war]. SEDA. ISBN 5-85973-012-8. (in Russian)

- ^ "Russia's unknown Circassian genocide". dispropaganda. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Grigori F. Krivosheev Россия и СССР в войнах XX в. Потери вооружённых сил. Олма-Пресс, 2001.: Вооружённые конфликты на Северном Кавказе (1920—2000 гг.). p.568

- ^ "Private letter on the capture of Shamil (Russian)". 2 September 1859. Retrieved 31 December 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Hozhay, Dalhan (1998). Чеченцы в русско-кавказской войне [Chechens in the Russian-Caucasian war]. SEDA. ISBN 5-85973-012-8. (in Russian)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Victimario Histórico Militar".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Jembulat Bolotoko: The Prince of Princes (Part One)". Jamestown. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. ISBN 9780813560694.

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. ISBN 9780813560694.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Ahmed 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok | Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ McCarthy 1995:53, fn. 45

- ^ Jump up to: a b King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517775-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henze 1992

- ^ King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom.

- ^ Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ King 2008:96

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shenfield 1999

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gazetesi, Aziz ÜSTEL, Star. "Soykırım mı; işte Çerkes soykırımı - Yazarlar - Aziz ÜSTEL | STAR". Star.com.tr. Retrieved 26 September 2020. Cite error: The named reference ":3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). Cite error: The named reference ":3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Эльмесова, А. М. ИЗ ИСТОРИИ РУССКО-КАВКАЗСКОЙ ВОЙНЫ.

- ^ Ahmed 2013, p. 161.

- ^ L.V.Burykina. Pereselenskoye dvizhenie na severo-zapagni Kavakaz. Reference in King.

- ^ Richmond 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Shenfield, Stephen D. The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide?, 1999

- ^ Jump up to: a b Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Shenfield 1999:150

- ^ Mackie p.11

- ^ Baddeley, preface

- ^ Ein Blick auf die Circassianer

- ^ Natho, Kadir I. Circassian History. Page 357.

- ^ Ruslan, Yemij (August 2011). Soçi Meclisi ve Çar II. Aleksandr ile Buluşma.

- ^ Baddeley p.344

- ^ Henze, Paul B. The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance Towards The Muslim World

- ^ Hatk, Isam Journal "Al-Waha"-"Oasis", Amman 1992

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ p. 55. He says nothing about the Abadzeks.

- ^ p. 156

- ^ "Jembulat Bolotoko: The Prince of Princes (Part One)". Jamestown. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ 6. AKAK, v. 5, p. 872.

- ^ Ibid., p. 873.

- ^ King, Ghost of Freedom, p47-49. Quote on p48:This, in turn, demanded...above all the stomach to carry the war to the highlanders themselves, including putting aside any scruples about destroying, forests, and any other place where raiding parties might seek refuge... Targeted assassinations, kidnappings, the killing of entire families and the disproportionate use of force became central to Russian operations...

- ^ Jump up to: a b King, The Ghost of Freedom, 74

- ^ Circassia, Unrepresented Nations and People Organisation (UNPO) (). Retrieved on April 4 2007

- ^ Baddeley p.92

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Baddeley p.73

- ^ Richmond, page 56

- ^ Jump up to: a b Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ King, Ghost of Freedom, p93-94

- ^ King, Ghost of Freedom, pp. 47–49. Quote on p. 48:This, in turn, demanded ... above all the stomach to carry the war to the highlanders themselves, including putting aside any scruples about destroying, forests, and any other place where raiding parties might seek refuge. ... Targeted assassinations, kidnappings, the killing of entire families and the disproportionate use of force became central to Russian operations...

- ^ King, The Ghost of Freedom, p73-76. p74:"The hills, forests and uptown villages where highland horsemen were most at home were cleared, rearranged or destroyed... to shift the advantage to the regular army of the empire."... p75:"Into these spaces Russian settlers could be moved or "pacified" highlanders resettled."

- ^ King, Ghost of Freedom, pp. 93–94

- ^ Henze, Paul B. The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance Towards The Muslim World

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Baddeley p.135

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Karpat, Kemal H. Ottoman population 1830–1914, 1985

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Potto V. Kavkazskaya Voina, v.2, p. 45

- ^ "JEMBULAT BOLOTOKO: PRENSLERİN PRENSİ (PŞIXEM 'ARİPŞ*)". cherkessia.net. 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Ibid., p. 59.

- ^ Sherbina F. A. Istoriya Armavira I Cherkeso-gayev (Ekaterinodar, 1916), p. 11.

- ^ Bell, James. Journal of a residence…, p. 422.

- ^ "Son Haber | 21 Mayıs 1864 Çerkes Soykırımı". Son Haber (in Turkish). 20 May 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Rajović, G. & Ezhevski, D.O. & Vazerova, A.G. & Trailovic, M.. (2018). The Tactics and Strategy of General G.Kh. Zass in the Caucasus. Bylye Gody. 50. 1492-1498. 10.13187/bg.2018.4.1492.

- ^ Duvar, Gazete (14 September 2020). "Kafkasya'nın istenmeyen Rus anıtları: Kolonyal geçmişi hatırlatıyorlar". Gazeteduvar (in Turkish). Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2 September 2013). "Velyaminov, Zass ve insan kafası biriktirme hobisi". Jıneps Gazetesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Bianet :: Çerkeslerden Rusya'ya: Kolonyalist politikalarınız nefret ekiyor". m.bianet.org. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richmond, Walter (2 September 2013). "Velyaminov, Zass ve insan kafası biriktirme hobisi". Jıneps Gazetesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Duvar, Gazete (14 September 2020). "Kafkasya'nın istenmeyen Rus anıtları: Kolonyal geçmişi hatırlatıyorlar". Gazeteduvar (in Turkish). Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "ЗАСС Григорий Христофорович фон (1797–1883), барон, генерал от кавалерии, герой Кавказской войны". enc.rusdeutsch.ru. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ История Армавира и черкесо-горцев. — Екатеринодар: Электро-тип. т-во «Печатник», 1916.

- ^ Dönmez, Yılmaz (31 May 2018). "General Zass'ın Kızının Adigeler Tarafından Kaçırılışı". ÇERKES-FED (in Turkish). Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "JEMBULAT BOLOTOKO: PRENSLERİN PRENSİ (PŞIXEM 'ARİPŞ*)". cherkessia.net. 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Mackie p.207

- ^ Baddeley p.313

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Mackie p.207

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Russian-Circassian War Circassianworld.com (2005). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Karpat, Kemal H. Ottoman population 1830–1914, 1985

- ^ Jump up to: a b King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Page 94. In a policy memorandum in of 1857, Dmitri Milyutin, chief-of-staff to Bariatinskii, summarized the new thinking on dealing with the northwestern highlanders. The idea, Milyutin argued, was not to clear the highlands and coastal areas of Circassians so that these regions could be settled by productive farmers...[but] Rather, eliminating the Circassians was to be an end in itself – to cleanse the land of hostile elements. Tsar Alexander II formally approved the resettlement plan...Milyutin, who would eventually become minister of war, was to see his plans realized in the early 1860s.

- ^ L.V.Burykina. Pereselenskoye dvizhenie na severo-zapagni Kavakaz. Reference in King.

- ^ Richmond 2008, p. 79. "In his memoirs Milutin, who proposed deporting Circassians from the mountains as early as 1857, recalls: "the plan of action decided upon for 1860 was to cleanse [ochistit'] the mountain zone of its indigenous population.".

- ^ Mackie p.275

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richmond, Walter. Circassian Genocide. Page 72

- ^ Prof.Dr. ĞIŞ Nuh (yazan), HAPİ Cevdet Yıldız (çeviren). Adigece'nin temel sorunları-1[dead link]. Адыгэ макъ,12/13 Şubat 2009

- ^ "We Will Not Forget the Circassian Genocide!". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "UNPO: The Circassian Genocide". unpo.org. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Coverage of The tragedy public Thought (later half of the 19th century), Niko Javakhishvili, Tbilisi State University, 20 December 2012, retrieved 1 June 2015

- ^ "The Circassian exile: 9 facts about the tragedy". The Circassian exile: 9 facts about the tragedy. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Neumann, Karl Friedrich Russland und die Tscherkessen, 1840

- ^ Karpat, Kemal H. Ottoman population 1830–1914, 1985

- ^ Levene, Mark Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State p. 297

- ^ Leitzinger, Antero. "The Circassian Genocide". The Eurasian Politician, Issue 2 (October 2000), Available at circassianworld.com, retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ Abzakh, Edris. Circassian History. University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences] (1996). Retrieved on March 11 2007

- ^ The Circassian Genocide. Unrepresented Nations and People Organisation (UNPO) (). Retrieved on April 4 2007

More References[]

- Henze, Paul B. 1992. "Circassian resistance to Russia." In Marie Bennigsen Broxup, ed., The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance Towards The Muslim World. London: C Hurst & Co, 266 pp. (Also New York: St. Martin's Press, 252 pp.) Part of it can be found here. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- Richmond, Walter (2008). The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present, Future. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77615-8. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007: Chapter 4 (excerpt)CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- Tsutsiev, Arthur, Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, 2014

Further reading[]

- Baddeley, John F. (1908). The Russian conquest of the Caucasus. London: Longmans, Green and Co. ISBN 0-7007-0634-8. OL 3428695M.

- Goble, Paul. 2005. Circassians demand Russian apology for 19th century genocide. Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 15 July 2005, 8(23).

- Karpat, Kemal H. 1985. Ottoman Population, 1830–1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Levene, Mark. 2005. Genocide in the Age of the Nation State. London; New York: I.B. Tauris.

- King, Charles. 2008. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Mackie, J[ohn] Milton. 1856. Life of Schamyl: and narrative of the Circassian War of independence against Russia. ISBN 1-4255-2996-8

- McCarthy, Justin. 1995. Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–1922. Princeton, New Jersey: Darwin. Chapter 2: Eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus.

- Neumann, Karl Friedrich. 1840. Russland und die Tscherkessen. Stuttgart und Tübingen: J. G. Cotta. In PDF through Internet Archive

- Shenfield, Stephen D. 1999. The Circassians: a forgotten genocide?. In Levene, Mark and Penny Roberts, eds., The massacre in history. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. Series: War and Genocide; 1. 149–162.

- Unrepresented Nations and People Organisation (UNPO). 2004. The Circassian Genocide, 2004-12-14.

- Ibid. 2006. Circassia: Adygs Ask European Parliament to Recognize Genocide, 2006-10-16.

- Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 – Bell, James Stanislaus (English)

- The Annual Register. 1836. United Kingdom

- Butkov, P.G. 1869. Materials for New History of the Caucasus 1722–1803.

- Jaimoukha, A., The Circassians: A Handbook, London: RoutledgeCurzon; New York; Routledge and Palgrave, 2001.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael. 2002. Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Series: Indiana-Michigan series in Russian and East European studies.

- Leitzinger, Antero. 2000. The Circassian Genocide. In The Eurasian Politician, 2000 October 2000, Issue 2.

- Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide, Rutgers University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780813560694

- Shapi Kaziev. Kaziev, Shapi. Imam Shamil. "Molodaya Gvardiya" publishers. Moscow, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010

Notes[]

- ^ The Ottoman Empire accepted to harbour the Muslim Circassians who were exiled during the Circassian genocide, 800,000–1,500,000 Circassians[35][36][37][44][45][39] (at least 75% of the total population) were exiled to Ottoman territory.[42][46] Different smaller numbers ended up in neighbouring Persia. During the process, the Russian and Cossack forces used various brutal methods to entertain themselves and scare off the native Circassians, such as tearing the bellies of pregnant women and removing the baby inside, then feeding the babies to dogs.[47] Russian generals such as and Grigory Zass allowed their soldiers to rape Circassian girls aged older than 7.[48]

External links[]

- Abzakh, Edris. 1996. Circassian History.

- Adanır, Fikret. 2007. Course syllabus with useful reading list.

- Hatk, Isam. 1992. Russian–Circassian War, 1763 – 21 May 1864. Al-Waha-Oasis, 1992, 51:10–15. Amman.

- Köremezli İbrahim. 2004. The Place of the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Circassian War (1830–1864). Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey.

- A collection of cited reports on the conflict, collected by the Circassian World, translated by Nejan Huvaj, and found on this page. Retrieved 11 March 2007

- Circassians

- 18th-century conflicts

- 19th-century conflicts

- 18th-century military history of the Russian Empire

- 19th-century military history of the Russian Empire

- 1763 in the Russian Empire

- 1864 in the Russian Empire

- Caucasian War

- Wars involving Chechnya

- Wars involving Russia

- Wars involving the Circassians