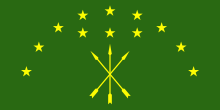

Circassians in Turkey

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Estimated 2,000,000[1][2][3][4]–3,000,000[5] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Circassian languages (including East Circassian and West Circassian dialects) Turkish Arabic (Hatay Circassians) | |

| Religion | |

| Primarily Islam Rarely Eastern Orthodox Church,[6] Circassian native faith Khabzeism[7] as well as Atheism-Agnosticism[8] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abazins, Abkhazians, Chechens |

| Part of a series on |

| Circassians |

|---|

|

| Circassian diaspora by region or country |

| Circassian Tribes |

|

Surviving Destroyed or barely alive |

| Religion in Circassia |

|

| Languages and dialects |

|

| History |

|

Medieval

Contemporary

|

| Culture |

|

Circassians in Turkey (East Circassian and West Circassian: Адыгэхэр Тырку, Adıgəxər Tırku; Turkish: Türkiye Çerkesleri, lit. 'Turkey Circassians') refers to people born in or residing in Turkey who are of Circassian origin. The Circassians are one of the largest ethnic minorities in Turkey, with a population estimated to be 2.5 million. According to the EU reports there are three to five million Circassians in Turkey.[9] The term was also formerly used to refer to all North Caucasians from Turkey.

Circassians are a Caucasian immigrant people, and although the Circassians in Turkey were forced to forget their language and assimilate into Turkish, a small minority still speak their native Circassian languages as it is still spoken in many Circassian villages, and the group that preserved their language the best are the Kabardians.[10] With the rise of Circassian nationalism in the 21st century, Circassians in Turkey, especially the young, have started to study and learn their language. The Circassians in Turkey are mostly Sunni Muslims of Hanafi madh'hab, although non-denominationalism is also fairly common among Circassians. The largest association of Circassians in Turkey,[11] , is the founding member of the International Circassian Association (ICA).[12]

The closely related ethnic groups Abazins (10,000[13]) and Abkhazians (39,000[14]) are also often counted among them.

History[]

This section may contain an excessive number of citations. (December 2020) |

The Circassian genocide was the Russian Empire's systematic mass murder,[15][16][17][18] ethnic cleansing,[19][16][17][18] forced migration[20][16][17][18]-expulsion[21][16][17][18] of 800,000–1,500,000 Circassians[22][23][16][17][18] (at least 75% of the total population) from their homeland Circassia. This occurred in the aftermath of the Caucasian War in the second half of the 19th century.[24] The displaced people were settled primarily to the Ottoman Empire, especially modern-day Turkey.[22] Much of Adyghe culture was disrupted after the conquest of their homeland by Russia in 1864.

Circassians are regarded by historians to play a key role in the history of Turkey. Turkey has the largest Adyghe population in the world, around half of all Circassians live in Turkey, mainly in the provinces of Samsun and Ordu (in Northern Turkey), Kahramanmaraş (in Southern Turkey), Kayseri (in Central Turkey), Bandırma, and Düzce (in Northwest Turkey), along the shores of the Black Sea; the region near the city of Ankara. All citizens of Turkey are considered Turks by the government, but it is estimated that approximately two million ethnic Circassians live in Turkey. The "Circassians" in question do not always speak the languages of their ancestors, and in some cases some of them may describe themselves as "only Turkish". The reason for this loss of identity is mostly due to Turkey's governmen assimilation policies[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32] [33][34][35][36][37][38] and marriages with non-Circassians.

Circassians are regarded by historians to play a key role in the history of Turkey. Some of the exilees and their descendants gained high positions in the Ottoman Empire. Most of the Young Turks were of Circassian origin. Until the end of the First World War, many Circassians actively served in the army. In the period after the First World War, Circassians came to the fore in Anatolia as a group of advanced armament and organizational abilities as a result of the struggle they fought with the Russian troops until they came to the Ottoman lands. However, the situation of the Ottoman Empire after the war caused them to be caught between the different balances of power between Istanbul and Ankara and even become a striking force. For this period, it is not possible to say that Circassians all acted together as in many other groups in Anatolia. The Turkish government removed 14 Circassian villages from Gönen and Manyas regions in December 1922, May and June 1923, without separating women and children, and drove them to different places in Anatolia from Konya to Sivas and Bitlis. This incident had a great impact on the assimilation of Circassians.

After 1923, Circassians were restricted by policies such as the prohibition of Circassian language,[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][30] changing village names, and surname law.[47][48][49] Circassians, who had many problems in maintaining their identity comfortably, were seen as a group that inevitably had to be assimilated.

Demographics[]

| Year | As first language | As second language | Total | Turkey's population | % of Total speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | 95,901 | 0 | 95,901 | 13,629,488 | 0.70 |

| 1935 | 91,972 | 14,703 | 106,675 | 16,157,450 | 0.66 |

| 1945 | 66,691 | 9,779 | 76,470 | 18,790,174 | 0.41 |

| 1950 | 75,837 | 0 | 75,837 | 20,947,188 | 0.36 |

| 1955 | 77,611 | 22,861 | 100,407 | 24,064,763 | 0.42 |

| 1960 | 63,137 | 65,061 | 128,198 | 27,754,820 | 0.46 |

| 1965 | 58,339 | 48,621 | 106,960 | 31,391,421 | 0.34 |

In the census of 1965, those who spoke Circassian as first language were proportionally most numerous in Kayseri (3.2%), Tokat (1.2%) and Kahramanmaraş (1.0).

Notable Circassian people with origins from Turkey[]

Politicians[]

- Ali Kemal - a Circassian-Turkish journalist who was killed during the Turkish War of Independence.

- Deniz Baykal – politician who was a long-time leader of the Republican People's Party (CHP) in Turkey.

- Cem Özdemir – politician, co-chairman of the German Green Party.

Presidents and prime ministers of Turkey[]

- Ahmet Necdet Sezer – 10th president of Turkey.[51]

- Ali Fethi Okyar – diplomat and politician, who also served as a military officer and diplomat during the last decade of the Ottoman Empire. He was also the second Prime Minister of Turkey (1924–1925) and the second Speaker of the Turkish Parliament after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[52][53]

- Recep Peker – military officer and politician. He served in various ministerial posts and finally as the Prime Minister of Turkey.[54]

- Necmettin Erbakan – politician, engineer, and academic who was the Prime Minister of Turkey from 1996 to 1997. He was pressured by the military to step down as prime minister and was later banned from politics by the Constitutional Court of Turkey for violating the separation of religion and state[55][56] as mandated by the constitution.[57][58]

Grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire[]

- Abaza Siyavuş Pasha I - Ottoman grand vizier (the index I is used to differentiate him from the second and better known Abaza Siyavuş Pasha, who also served as grand vizier, from 1687 to 1688). (Abkhazian)

- Abaza Siyavuş Pasha - Grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire who held the post during one of the most chaotic periods of the empire. (Abkhazian)

- Salih Hulusi Pasha - One of the last Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire, under the reign of the last Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI. (Abkhazian)

- Cenaze Hasan Pasha - Short-term Ottoman grand vizier in 1789. His epithet Cenaze (or Meyyit) means "corpse" because he was ill when appointed to the post.

- Melek Ahmed Pasa - Ottoman statesman and grand vizier during the reign of Mehmed IV. (Abkhazian)

- Ibşir Mustafa Pasha - Ottoman statesman. He was grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 28 October 1654 to 11 May 1655. He was also the Ottoman governor of Damascus Eyalet (province) in 1649. He was a damat ("bridegroom") to the Ottoman dynasty, as he married an Ottoman princess.

- Koca Dervish Mehmed Pasha - Ottoman military officer and statesman from Circassia. He was made Kapudan Pasha (Grand Admiral) in 1652 and promoted to Grand Vizier on 21 March 1653. He held the position until 28 October 1654.[59][60]

- Çerkes Mehmed Pasha - Ottoman statesman who served as Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1624 to 1625.[61]

- Hayreddin Pasha - Ottoman politician. First serving as Beylerbeyi of Ottoman Tunisia, he later achieved the high post of Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. He was a political reformer during a period of growing European ascendancy. was a pragmatic activist who reacted against poor conditions in Muslim states, and looked to Europe for solutions. He applied the Islamic concept of "maṣlaḥah" (or public interest), to economic issues. He emphasized the central role of justice and security in economic development. He was a major advocate of "tanẓīmāt" (or modernization) for Tunisia's political and economic systems.[62] (Abkhazian)

- Koca Hüsrev Mehmed Pasha - Ottoman admiral, reformer and statesman, who was Kapudan Pasha of the Ottoman Navy. He reached the position of Grand Vizier rather late in his career, between 2 July 1839 and 8 June 1840 during the reign of Abdulmejid I. However, during the 1820s, he occupied key administrative roles in the fight against regional warlords, the reformation of the army, and the reformation of Turkish attire. He was one of the main statesmen who predicted a war with the Russian Empire who exiled his ancestors, which would eventually be the case with the outbreak of the Crimean War.[63] (Abkhazian)

- Özdemiroğlu Osman Pasha - Ottoman statesman and military commander who also held the office of grand vizier.

Military officiers[]

- Çerkes Ethem – Militia leader who initially gained fame for gaining victories against the Allied powers invading Anatolia in the aftermath of World War I and afterwards during the Turkish War of Independence.[64][65][66]

- Hulusi Akar – Turkish Minister of Defense and a former four-star Turkish Armed Forces general who served as the 29th Chief of the Turkish General Staff.[67] Akar also served as a brigade commander in various NATO engagements including the International Security Assistance Force against the Taliban insurgency, Operation Deliberate Force during the Bosnian War, the Kosovo Force during the Kosovo War, as well as overseeing much of the Turkish involvement in the Syrian Civil War.

- Yakub Cemil - Revolutionary and soldier, who assassinated Nazım Pasha during the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état.[68]

- Ahmet Fevzi Big - Commander of the Ninth Army Corps of the Ottoman Third Army. He was an Abkhazian immigrant from Düzce.[69]

- Ahmet Anzavur - Ottoman officier who revolted and occupied the Marmara Region.

- Bekir Sami Kunduh - Also served as the first Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey during 1920–1921.[70]

- Cemil Cahit Toydemir - Officer of the Ottoman Army and a general of the Turkish Army.

Cultural figures[]

- Tevfik Esenç – Last known fully competent speaker of the Ubykh language.

Film, TV, and stage[]

- Mehmet Oz - Surgeon who hosts the TV program "The Dr.Oz show".

- Elçin Sangu - Actress known for her role in "Kiralık Aşk".

- - Model, actress.

- - Actor.

- Ali İhsan Varol - TV show presenter, producer, and actor.

- İrem Sak - Actress and singer.

- - Writer and director.

Ahmet Kabolati - writer/director/producer of film and television (known for The Final, Pendulum, Mind of its Own).

Musicians[]

- Hadise - Singer.

- Türkan Şoray - Singer.

Writers[]

- Ömer Seyfettin - writer.

Sports people[]

- Altay Bayındır – Professional footballer who plays as goalkeeper

- Emre Belözoğlu – Former professional footballer who played as a midfielder, manager

- Şamil Çinaz – Professional footballer who plays as a midfielder

- Can Bartu – Former professional basketball and football player and pundit

- Ayetullah Bey – Former professional footballer, founder and second president of the major Turkish multi-sport club Fenerbahçe SK

- Mahmut Atalay – Wrestler, 1968 Olympic Gold medalist.

- Hamit Kaplan – Wrestler, 1956 Olympic Gold medalist.

- Süleyman Seba – Ex-President of Besiktas Football Club.

- Yaşar Doğu – 1948 London Olympics middleweight wrestling champion.

- Sefer Baygin – 1972 Europe wrestling champion.

See also[]

- Minorities in Turkey

- Circassians in Iran

- Circassians in Syria

- Circassians in Iraq

- Peoples of the Caucasus in Turkey

References[]

- ^ Circassia, Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, archived from the original on 2010-11-29.

- ^ Ülkü Bilgin: Azınlık hakları ve Türkiye. Kitap Yayınevi, Istanbul 2007; S. 85. ISBN 975-6051-80-9 (Turkish Language)

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0813560694.

- ^ Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 528. ISBN 978-1317464006.

- ^ Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ James Stuart Olson, ed. (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-313-27497-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ 2012 Survey Maps. "Ogonek". No 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Svetlana Lyagusheva (2005). "Islam and the Traditional Moral Code of Adyghes". Iran and the Caucasus. Brill. 9 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1163/1573384054068123. JSTOR 4030903.

- ^ Bernard Lewis. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. p. 94.

- ^ Papşu, Murat (2003). Çerkes dillerine genel bir bakış Kafkasya ve Türkiye Archived 10 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Nart Dergisi, Mart-Nisan 2003, Sayı:35

- ^ Адыгэхэм я щыгъуэ-щIэж махуэм къызэрагъэпэща пэкIур Тыркум гулъытэншэу къыщагъэнакъым[dead link]. 2012-06-09 (Çerkesçe)

- ^ "Kafkas Dernekleri Federasyonu İlkeleri". Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Ethnologue: Abasinen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Ethnologue: Abchasen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "We Will Not Forget the Circassian Genocide!". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok | Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "UNPO: The Circassian Genocide". unpo.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Coverage of The tragedy public Thought (later half of the 19th century), Niko Javakhishvili, Tbilisi State University, 20 December 2012, retrieved 1 June 2015

- ^ "The Circassian exile: 9 facts about the tragedy". The Circassian exile: 9 facts about the tragedy. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Ahmed 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Yemelianova, Galina, Islam nationalism and state in the Muslim Caucasus. April 2014. pp. 3

- ^ Ayhan Aktar, "Cumhuriyet’in Đlk Yıllarında Uygulanan ‘Türklestirme’ Politikaları," in Varlık Vergisi ve 'Türklestirme' Politikaları,2nd ed. (Istanbul: Iletisim, 2000), 101.

- ^ Davison, Roderic H. (2013). Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774-1923: The Impact of the West. University of Texas Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0292758940. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı; Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528.

- ^ Soner, Çağaptay (2006). Otuzlarda Türk Milliyetçiliğinde Irk, Dil ve Etnisite (in Turkish). İstanbul. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. 18 (4): 400. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2005.00262.x. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Suny, edited by Ronald Grigor; Goçek,, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (23 February 2011). A question of genocide : Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ İnce, Başak (26 April 2012). Citizenship and identity in Turkey : from Atatürk's republic to the present day. Londra: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-026-1.

- ^ Kieser, ed. by Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey beyond nationalism: towards post-nationalist identities ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Londra [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 45. ISBN 9781845111410. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Ertürk, Nergis (19 October 2011). Grammatology and literary modernity in Turkey. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199746682.

- ^ Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. Vol. 18 no. 4. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı & Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ editor, Sibel Bozdoǧan, Gülru Necipoğlu, editors ; Julia Bailey, managing (2007). Muqarnas : an annual on the visual culture of the Islamic world. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004163201.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Aslan, Senem (17 May 2007). ""Citizen, Speak Turkish!": A Nation in the Making". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 13 (2): 245–272. doi:10.1080/13537110701293500. S2CID 144367148.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor; Göçek, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (2 February 2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978104-1.

- ^ Ayhan Aktar, "Cumhuriyet’in Đlk Yıllarında Uygulanan ‘Türklestirme’ Politikaları," in Varlık Vergisi ve 'Türklestirme' Politikaları,2nd ed. (Istanbul: Iletisim, 2000), 101.

- ^ Soner, Çağaptay (2006). Otuzlarda Türk Milliyetçiliğinde Irk, Dil ve Etnisite (in Turkish). İstanbul. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Kieser, ed. by Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey beyond nationalism: towards post-nationalist identities ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Londra [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 45. ISBN 9781845111410. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Ertürk, Nergis (19 October 2011). Grammatology and literary modernity in Turkey. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199746682.

- ^ Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. Vol. 18 no. 4. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı & Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528.

- ^ editor, Sibel Bozdoǧan, Gülru Necipoğlu, editors ; Julia Bailey, managing (2007). Muqarnas : an annual on the visual culture of the Islamic world. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004163201.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Aslan, Senem (April 2007). ""Citizen, Speak Turkish!": A Nation in the Making". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. Vol. 13 no. 2. Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 245–272.

- ^ Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. 18 (4): 400. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2005.00262.x. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Suny, edited by Ronald Grigor; Goçek,, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (23 February 2011). A question of genocide : Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ İnce, Başak (26 April 2012). Citizenship and identity in Turkey : from Atatürk's republic to the present day. Londra: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-026-1.

- ^ Fuat Dündar, Türkiye Nüfus Sayımlarında Azınlıklar, 2000

- ^ Circassian Diaspor: Israeli Circassians, Turkish People of Circassian Descent, Mehmed VI, Nāzim Hikmet, Hadise, Mehmet Oz, Kāzim Karabekir. Books LLC. August 2011. ISBN 9781233081905.

- ^ "Çerkesler listesi", Vikipedi (in Turkish), 2020-12-06, retrieved 2020-12-11

- ^ Türkiye Kurtuluş Savaşı'nda Çerkes göçmenleri at Google Books

- ^ Berzeg, Sefer E. (1990). Türkiye Kurtuluş Savaşı'nda Çerkes göçmenleri (in Turkish). Nart Yayıncılık.

- ^ [1] BBC. Turkey Bans Islamists, January 1998

- ^ [2] BBC. Ex-Turkish PM sentenced, March 2000

- ^ "Necmettin Erbakan Kimdir?". Archived from the original on 28 March 2020.

- ^ "13 Aralık 2010 - Aksiyon dergisi röportajı: "Bir yanımız anne tarafından Çerkez"". Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ S. H. Longrigg, Four centuries of modern Iraq, Oxford 1925

- ^ H. Laoust, Les Governeurs de Damas sous les Mamlouks et les premiers ottomans (1260-1744), Damasc 1952

- ^ İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, Türkiye Yayınevi, İstanbul, 1971 (Turkish)

- ^ Abdul Azim Islahi, "Economic ideas of a nineteenth century Tunisian statesman: Khayr al-Din al-Tunisi." Hamdard Islamicus (2012): 61-80 online.

- ^ Emiroğlu, Kudret (2016). Kısa Osmanlı-Türkiye Tarihi: Padişahlık Kültürü ve Demokrasi Ülküsü (in Turkish). İletişim Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-05-2067-9.

- ^ Çerkes Ethem [attributed] (2014). Hatıralarım (Çerkes trajedisinin 150. yılında) [My Memoirs] (in Turkish). Istanbul: Bizim Kitaplar. ISBN 9786055476465.

- ^ "Çerkes Ethem Kendini Savunuyor: Vatan İçin İlk Ben Yola Çıktım" [Ethem the Circassian defends himself: I Took the Initiative for the Homeland]. Radikal (in Turkish). Istanbul. 9 November 2014.

- ^ Salihoğlu, M. Latif (21 September 2015). "Çerkes Ethem'e Resmen İade-i İtibar" [Official Restoration of Honour for Ethem the Circassian]. Yeni Asya (in Turkish). Istanbul.

- ^ "Yeni Genelkurmay Başkanı Hulusi Akar oldu (Hulusi Akar kimdir?)" [Who is our new Chief of the General Staff Hulusi Akar?]. Haber Türk (in Turkish). Istanbul. 16 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Tansu, Samih Nafiz. "İttihat ve Terakki, Ya Devlet Başa, Ya Kuzgun Leşe" (in Turkish).

- ^ Gingeras, Ryan (2009-02-26). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire 1912-1923. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956152-0.

- ^ Biography on biyografi.net

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Circassian people in Turkey. |

- Circassians

- Circassian diaspora

- Demographics of Turkey

- European diaspora in Turkey

- Turkish people of Circassian descent

- Ethnic groups in the Middle East