Silibinin

This article relies too much on references to primary sources. (February 2019) |

| |

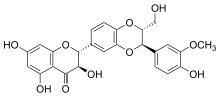

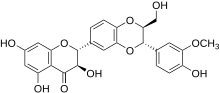

Silibinin A and silibinin B structures | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral and Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.168 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H22O10 |

| Molar mass | 482.441 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| | |

Silibinin (INN), also known as silybin (both from Silybum, the generic name of the plant from which it is extracted), is the major active constituent of silymarin, a standardized extract of the milk thistle seeds, containing a mixture of flavonolignans consisting of silibinin, , silychristin, , and others. Silibinin itself is a mixture of two diastereomers, silybin A and silybin B, in approximately equimolar ratio.[1] The mixture exhibits a number of pharmacological effects, particularly in the fatty liver, non-alcoholic fatty liver, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and there is great clinical evidence for the use of silibinin as a supportive element in alcoholic and Child–Pugh grade 'A' liver cirrhosis.[2] However, despite its several beneficial effects on the liver, silibinin and all the other compounds found in silymarin, especially silychristin seem to act as potent disruptors of the thyroid system by blocking the MCT8 transporter.[3] The long term intake of silymarin can lead to some form of thyroid disease and if taken during pregnancy, silymarin can cause the development of the Allan–Herndon–Dudley syndrome.[3] Although this information is unfortunately still not being taken into consideration by all regulatory bodies, several studies now consider silymarin and especially silychristin to be important inhibitors of the MCT8 transporter and a potential disruptor of the thyroid hormone functions.[3]

Pharmacology[]

Poor water solubility and bioavailability of silymarin led to the development of enhanced formulations. Silipide (trade name Siliphos, not to be confused with the water treatment compound of the same name, a glass-like polyphosphate containing sodium, calcium magnesium and silicate, formulated for the treatment of water problems), a complex of silymarin and phosphatidylcholine (lecithin), is about 10 times more bioavailable than silymarin.[4] An earlier study had concluded Siliphos to have 4.6 fold higher bioavailability.[5][non-primary source needed] It has been also reported that silymarin inclusion complex with β-cyclodextrin is much more soluble than silymarin itself.[6] There have also been prepared glycosides of silybin, which show better water solubility and even stronger hepatoprotective effect.[7]

Silymarin, like other flavonoids, has been shown to inhibit P-glycoprotein-mediated cellular efflux.[8] The modulation of P-glycoprotein activity may result in altered absorption and bioavailability of drugs that are P-glycoprotein substrates. It has been reported that silymarin inhibits cytochrome P450 enzymes and an interaction with drugs primarily cleared by P450s cannot be excluded.[9]

Toxicity[]

Several studies have documented the potentially dangerous effects of the silymarin mixture on the thyroid system. All of the flavonolignan compounds found in the silymarin mixture seem to block the uptake of thyroid hormones into the cells by selectively blocking the MCT8 transmembrane transporter.[3] The authors of this study noted that especially silychristin, one of the compounds of the silymarin mixture seems to be perhaps the most powerful and selective inhibitor for the MCT8 transporter.[3] Due to the essential role played by the thyroid hormone in human metabolism in general it is believed that the intake of silymarin can lead to disruptions of the thyroid system.[3] Because the thyroid hormones and the MCT8 as well are known to play a critical role during early and fetal development, the administration of silymarin during pregnancy is especially thought to be dangerous, potentially leading to the Allan–Herndon–Dudley syndrome, a brain development disorder that causes both moderate to severe intellectual disability and problems with speech and movement.[10]

A phase I clinical trial in humans with prostate cancer designed to study the effects of high dose silibinin found 13 grams daily to be well tolerated in patients with advanced prostate cancer with asymptomatic liver toxicity (hyperbilirubinemia and elevation of alanine aminotransferase) being the most commonly seen adverse event.[11]

Silymarin is also devoid of embryotoxic potential in animal models.[12][13]

Medical uses[]

Silibinin is available as drug (Legalon SIL (Madaus) (D, CH, A) and Silimarit (Bionorica), a Silymarin product) in many EU countries and used in the treatment of toxic liver damage (e.g. IV treatment in case of death cap poisoning); as adjunctive therapy in chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis.[citation needed]

For approved drug preparations and parenteral applications in the treatment of Amanita mushroom poisoning, the water-soluble silibinin-C-2',3-dihyrogensuccinate disodium salt is used. In 2011, the same compound also received Orphan Medicinal Product Designation for the prevention of recurrent hepatitis C in liver transplant recipients by the European Commission.[14]

Potential medical uses[]

Silibinin is under investigation to see whether it may have a role in cancer treatment (e.g. due to its inhibition of STAT3 signalling).[15]

Silibinin also has a number of potential mechanisms that could benefit the skin. These include chemoprotective effects from environmental toxins, anti-inflammatory effects, protection from UV induced photocarcinogenesis, protection from sunburn, protection from UVB-induced epidermal hyperplasia, and DNA repair for UV induced DNA damage (double strand breaks).[16] Studies on mice demonstrate a significant protection on chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) induced depressive-like behavior on mice[17] and increased cognition in aged rats as a result of consuming silymarin.[18]

Due to its immunomodulatory,[19] iron chelating and antioxidant properties, this herb has the potential to be used in beta-thalassemia patients who receive regular blood transfusions and suffer from iron overload.[20]

Biotechnology[]

Silymarin can be produced in callus and cells suspensions of Silybum marianum and substituted pyrazinecarboxamides can be used as abiotic elicitors of flavolignan production.[21]

Biosynthesis[]

The biosynthesis of silibinin A and silibinin B is composed of two major parts, taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol.[22][23] Coniferyl alcohol is synthesized in milk thistle seed coat. Starting with the transformation of phenylalanine into cinnamic acid mediated by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL).[24] Cinnamic acid will then go through two rounds of oxidation by trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase (C4H) and 4-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (C3H) to give caffeic acid. The meta position alcohol is methylated by caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase to produce ferulic acid. From ferulic acid, the production of coniferyl alcohol is carried out by 4-hydroxycinnamate CoA ligase (4CL), cinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR), and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD). For taxifolin, its genes for the biosynthesis can be overexpressed in flower as the transcription is light dependent. The production of taxifolin utilizes the similar pathway to synthesize p-coumaric acid followed by three times of carbon chain elongation with malonyl-CoA and cyclization by chalcone synthase and chalcone isomerase to yield naringenin. Through flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) and flavonoid 3'-monooxygenase (F3'H), taxifolin is furnished. To merge taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol, taxifolin can be translocated from the flower to the seed coat through symplast pathway. Both taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol will be oxidized by ascorbate peroxidase 1 (APX1) to enable the single electron reaction to couple two fragments generating silybin (silibinin A + silibinin B).

References[]

- ^ Davis-Searles P, Nakanishi Y, Nam-Cheol K, et al. (2005). "Milk Thistle and Prostate Cancer: Differential Effects of Pure Flavonolignans from Silybum marianum on Antiproliferative End Points in Human Prostate Carcinoma Cells" (PDF). Cancer Research. 65 (10): 4448–57. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4662. PMID 15899838.

- ^ Saller R, Brignoli R, Melzer J, Meier R (2008). "An updated systematic review with meta-analysis for the clinical evidence of silymarin". Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 15 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1159/000113648. PMID 18334810. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Johannes J, Jayarama-Naidu R, Meyer F, Wirth EK, Schweizer U, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Renko K (2016). "Silychristin, a Flavonolignan Derived From the Milk Thistle, Is a Potent Inhibitor of the Thyroid Hormone Transporter MCT8". Endocrinology. 157 (4): 1694–2301. doi:10.1210/en.2015-1933. PMID 26910310.

- ^ Kidd P, Head K (2005). "A review of the bioavailability and clinical efficacy of milk thistle phytosome: a silybin-phosphatidylcholine complex (Siliphos)" (PDF). Alternative Medicine Review. 10 (3): 193–203. PMID 16164374. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- ^ Barzaghi N, Crema F, Gatti G, Pifferi G, Perucca E (1990). "Pharmacokinetic studies on IdB 1016, a silybin- phosphatidylcholine complex, in healthy human subjects". Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 15 (4): 333–8. doi:10.1007/bf03190223. PMID 2088770.

- ^ Voinovich D, Perissutti B, Grassi M, Passerini N, Bigotto A (2009). "Solid state mechanochemical activation of Silybum marianum dry extract with betacyclodextrins: Characterization and bioavailability of the coground systems". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 98 (11): 4119–29. doi:10.1002/jps.21704. PMID 19226635.

- ^ Kosina P, Kren V, Gebhardt R, Grambal F, Ulrichová J, Walterová D (2002). "Antioxidant properties of silybin glycosides". Phytotherapy Research. 16 Suppl 1: S33–9. doi:10.1002/ptr.796. PMID 11933137.

- ^ Zhou S, Lim LY, Chowbay B (2004). "Herbal modulation of P-glycoprotein". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 36 (1): 57–104. doi:10.1081/DMR-120028427. PMID 15072439.

- ^ Wu JW, Lin LC, Tsai TH (2009). "Drug-drug interactions of silymarin on the perspective of pharmacokinetics". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 121 (2): 185–93. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.036. PMID 19041708.

- ^ "Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- ^ Thomas W. Flaig; Daniel L. Gustafson; Lih-Jen Su; Joseph A. Zirrolli; Frances Crighton; Gail S. Harrison; A. Scott Pierson; Rajesh Agarwal; L. Michael Glodé (2007). "A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of silybin-phytosome in prostate cancer patients". Investigational New Drugs. 25 (2): 139–146. doi:10.1007/s10637-006-9019-2. PMID 17077998.

- ^ Fraschini F, Demartini G, Esposti D (2002). "Pharmacology of Silymarin". Clinical Drug Investigation. 22 (1): 51–65. doi:10.2165/00044011-200222010-00007. Archived from the original on 2012-10-27.

- ^ Hahn G, Lehmann HD, Kürten M, Uebel H, Vogel G (1968). "On the pharmacology and toxicology of silymarin, an antihepatotoxic active principle from Silybum marianum (L.) gaertn". Arzneimittelforschung. 18 (6): 698–704. PMID 5755807.

- ^ Rottapharm|Madaus. Media Communications Legalon®. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Bosch-Barrera, Joaquim; Sais, Elia; Cañete, Noemí; Marruecos, Jordi; Cuyàs, Elisabet; Izquierdo, Angel; Porta, Rut; Haro, Manel; Brunet, Joan; Pedraza, Salvador; Menendez, Javier A. (2016). "Response of brain metastasis from lung cancer patients to an oral nutraceutical product containing silibinin". Oncotarget. 7 (22): 32006–32014. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.7900. PMC 5077992. PMID 26959886.

- ^ Singh, Rana P.; Agarwal, Rajesh (September 2009). "Cosmeceuticals and silibinin". Clinics in Dermatology. 27 (5): 479–484. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.05.012. PMC 2767273. PMID 19695480.

- ^ Thakare, Vishnu N; Patil, Rajesh R; Oswal, Rajesh J; Dhakane, Valmik D; Aswar, Manoj K; Patel, Bhoomika M (February 2018). "Therapeutic potential of silymarin in chronic unpredictable mild stress induced depressive-like behavior in mice". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 32 (2): 223–235. doi:10.1177/0269881117742666. ISSN 0269-8811. PMID 29215318.

- ^ Sarubbo, F.; Ramis, M. R.; Kienzer, C.; Aparicio, S.; Esteban, S.; Miralles, A.; Moranta, D. (March 2018). "Chronic Silymarin, Quercetin and Naringenin Treatments Increase Monoamines Synthesis and Hippocampal Sirt1 Levels Improving Cognition in Aged Rats". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 13 (1): 24–38. doi:10.1007/s11481-017-9759-0. ISSN 1557-1890. PMID 28808887.

- ^ Balouchi, Sima; Gharagozloo, Marjan; Esmaeil, Nafiseh; Mirmoghtadaei, Milad; Moayedi, Behjat (2014-08-01). "Serum levels of TGFβ, IL-10, IL-17, and IL-23 cytokines in β-thalassemia major patients: the impact of silymarin therapy". Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 36 (4): 271–274. doi:10.3109/08923973.2014.926916. ISSN 0892-3973. PMID 24945737.

- ^ Esfahani, Behjat Al-Sadat Moayedi; Reisi, Nahid; Mirmoghtadaei, Milad (2015-03-04). "Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of Silymarin in β-Thalassemia Patients: A Review". Hemoglobin. 39 (2): 75–80. doi:10.3109/03630269.2014.1003224. ISSN 0363-0269. PMID 25643967.

- ^ Tůmová L, Tůma J, Megušar K, Doleža M (2010). "Substituted Pyrazinecarboxamides as Abiotic Elicitors of Flavolignan Production in Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn Cultures in Vitro". Molecules. 15 (1): 331–340. doi:10.3390/molecules15010331. PMC 6256978. PMID 20110894.

- ^ Lv, Yongkun; Gao, Song; Xu, Sha; Du, Guocheng; Zhou, Jingwen; Chen, Jian (2017-11-11). "Spatial organization of silybin biosynthesis in milk thistle [Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn]". The Plant Journal. 92 (6): 995–1004. doi:10.1111/tpj.13736. ISSN 0960-7412. PMID 28990236.

- ^ Prasad, Ram Raj; Paudel, Sandeep; Raina, Komal; Agarwal, Rajesh (May 2020). "Silibinin and non-melanoma skin cancers". Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 10 (3): 236–244. doi:10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.02.003. ISSN 2225-4110. PMC 7340873. PMID 32670818.

- ^ Barros, Jaime; Escamilla-Trevino, Luis; Song, Luhua; Rao, Xiaolan; Serrani-Yarce, Juan Carlos; Palacios, Maite Docampo; Engle, Nancy; Choudhury, Feroza K.; Tschaplinski, Timothy J.; Venables, Barney J.; Mittler, Ron (2019-04-30). "4-Coumarate 3-hydroxylase in the lignin biosynthesis pathway is a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1994. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1994B. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10082-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6491607. PMID 31040279.

External links[]

- Review of the Quality of Evidence for Milk Thistle Use from MayoClinic.com

- Morazzoni P, Bombardelli E (1994). "Silybum marianum (cardus marianus)". Fitoterapia. 66: 3–42.

- Saller R, Meier R, Brignoli R (2001). "The use of silymarin in the treatment of liver diseases". Drugs. 61 (14): 2035–63. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161140-00003. PMID 11735632.

- Silymarin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Antidotes

- Flavonolignans

- Resorcinols

- 3-hydroxypropenals

- Benzodioxans