Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions,[3] are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts.[4][5][6][7] The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.[8][9][10][11]

The Northwest Semitic languages are a language group that contains the Aramaic language, as well as the Canaanite languages including Phoenician and Hebrew.

Languages[]

The old Aramaic period (850 to 612 BC) saw the production and dispersal of inscriptions due to the rise of the Arameans as a major force in Ancient Near East. Their language was adopted as an international language of diplomacy, particularly during the late stages of the Neo-Assyrian Empire as well as the spread of Aramaic speakers from Egypt to Mesopotamia.[12] The first known Aramaic inscription was the Carpentras Stela, found in southern France in 1704; it was considered to be Phoenician text at the time.[13][14]

Only 10,000 inscriptions in Phoenician-Punic, a Canaanite language, are known,[7][15] such that "Phoenician probably remains the worst transmitted and least known of all Semitic languages."[16] The only other substantial source for Phoenician-Punic are the excerpts in Poenulus, a play written by the Roman writer Plautus.[7] Within the corpus of inscriptions only 668 words have been attested, including 321 hapax legomena (words only attested a single time), per Wolfgang Röllig's analysis in 1983.[17] This compares to the Bible's 7000–8000 words and 1500 hapax legomena, in Biblical Hebrew.[17][18] The first published Phoenician-Punic inscription was from the Cippi of Melqart, found in 1694 in Malta;[19] the first published such inscription from the Phoenician "homeland" was the Eshmunazar II sarcophagus published in 1855.[1][2]

Fewer than 2,000 inscriptions in Ancient Hebrew, another Canaanite language, are known, of which the vast majority comprise just a single letter or word.[20][21] The first detailed Ancient Hebrew inscription published was the Shebna inscription, found in 1870.[22][23]

List of notable inscriptions[]

The inscriptions written in ancient Northwest Semitic script (Canaanite and Aramaic) have been catalogued into multiple corpora (i.e. lists) over the last two centuries. The primary corpora to have been produced are as follows:

- Hamaker, Hendrik Arent (1828). Miscellanea Phoenicia, sive Commentarii de rebus Phoenicum, quibus inscriptiones multae lapidum ac nummorum, nominaque propria hominum et locorum explicantur, item Punicae gentis lingua et religiones passim illustrantur. S. et J. Luchtmans.: Hamaker's review assessed 13 inscriptions[24]

- Gesenius, Wilhelm (1837). Scripturae linguaeque Phoeniciae monumenta quotquot supersunt edita et inedita. 1–3. In the 1830s, only approximately 80 inscriptions and 60 coins were known in the entire Phoenicio-Punic corpus[24][25]

- Schröder, Paul (1869). Die phönizische sprache. Entwurf Einer Grammatik, Nebst Sprach- und Schriftproben.: The first study of Phoenician grammar, listed 332 texts known at the time[24][26]

- CIS: Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum; the first section is focused on Phoenician-Punic inscriptions (176 "Phoenician" inscriptions and 5982 "Punic" inscriptions)[4]

- KAI: Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften, considered the "gold standard" for the last fifty years[5]

- NSI: George Albert Cooke, 1903: Text-book of North-Semitic Inscriptions: Moabite, Hebrew, Phoenician, Aramaic, Nabataean, Palmyrene, Jewish[27]

- NE: Mark Lidzbarski, 1898: Handbuch der Nordsemitischen Epigraphik, nebst ausgewählten Inschriften: I Text and II Plates[27]

- KI: Lidzbarski, Mark (1907). Kanaanäische Inschriften (moabitisch, althebräisch, phönizisch, punisch). A. Töpelmann.

- TSSI: Gibson, J. C. L. (1971). Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions: I. Hebrew and Moabite Inscriptions. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-813159-5.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Sass, Benjamin (2013). The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology. Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel (HeBAI). 2. pp. 149–220. doi:10.1628/219222713X13757034787838.

The inscriptions listed below include those which are mentioned in multiple editions of the corpora above (the numbers in the concordance column cross-refer to the works above), as well as newer inscriptions which have been published since the corpora above were published (references provided individually).

| Name | Image | Discovered | Date | Location Found | Current Location | Concordance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAI | CIS / RES | NE | KI | NSI | TSSI | Ref. | ||||||

| Ahiram Sarcophagus |

|

1923 | 850 BC | Byblos | National Museum of Beirut | 1 | III 4 | |||||

| Byblos Necropolis graffito |

|

1922 | Byblos | in situ | 2 | III 5 | ||||||

| Byblos spatula | Byblos | National Museum of Beirut | 3 | III 1 | ||||||||

| Yehimilk inscription |

|

1930 | Byblos | Byblos Castle | 4 | III 6 | ||||||

| Abiba’l inscription |

|

1895 | Byblos | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 5 | R 505 | III 7 | |||||

| Osorkon Bust |

|

1881 | 900 BC | Byblos | Louvre | 6 | III 8 | |||||

| Safatba'al inscription |

|

1936 | Byblos | National Museum of Beirut | 7 | III 9 | ||||||

| Abda sherd graffito | Byblos | 8 | III 10 | |||||||||

| Son of Shipitbaal inscription |

|

400s BC | Byblos | National Museum of Beirut | 9 | |||||||

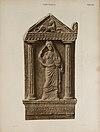

| Yehawmilk Stele |

|

1869 | 400s BC | Byblos | Louvre | 10 | I 1 | 416 | 5 | 3 | III 25 | |

| Batnoam inscription |

|

Byblos | National Museum of Beirut | 11 | III 26 | |||||||

| Byblos altar inscription | Byblos | 12 | ||||||||||

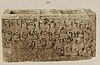

| Tabnit sarcophagus |

|

1887 | 500 BC | Sidon | Museum of the Ancient Orient | 13 | R 1202 | 417,1 | 6 | 4 | III 27 | |

| Eshmunazar II sarcophagus |

|

1855 | Sidon | Louvre | 14 | I 3, R 1506 | 417,2 | 7 | 5 | III 28 | ||

| Bodashtart inscriptions |

|

1858, 1900-2 | 300s BC | Sidon | Louvre and Museum of the Ancient Orient | 15–16 | I 4, R 766, 767 | 8–9 | 6, Appendix I | |||

| Throne of Astarte |

|

1907 | Tyre | Louvre and National Museum of Beirut | 17 | R 800 | 12 | III 30 | ||||

| Baalshamin inscription |

|

1864 | 132 BC | Umm al-Amad | Louvre | 18 | I 7 | 9 | ||||

| Masub inscription |

|

1885 | 222 BC | Masub | Louvre | 19 | R 1205 | 419e | 16 | 10 | III 31 | |

| Phoenician arrowheads | various | 20–22 | III p.6 | |||||||||

| Hasanbeyli inscription | 1894 | Hasanbeyli | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 23 | ||||||||

| Kilamuwa Stela |

|

1893 | Sam'al | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 24 | III 13 | ||||||

| Kilamuwa scepter | Sam'al | 25 | III 14 | |||||||||

| Karatepe bilingual |

|

1946 | Karatepe | Karatepe-Aslantaş Open-Air Museum | 26 | III 15 | ||||||

| Arslan Tash amulets |

|

1933 | Arslan Tash | National Museum of Aleppo | 27 | III 23 | ||||||

| Carchemish Phoenician inscription |

|

1950 | Carchemish | British Museum | 28 | |||||||

| Ur Box inscription | 1927 | Ur | British Museum | 29 | III 20 | |||||||

| Honeyman inscription |

|

1939 | 900 BCE | Cyprus | Cyprus Museum | 30 | III 12 | |||||

| Baal Lebanon inscription | 1877 | 700s BC | Cyprus | Cabinet des Médailles | 31 | I 5 | 419 | 17 | 11 | III 17 | ||

|

1860 | 341 BC | Cyprus | Louvre | 32 | I 10 | 420,1 | 18 | 12 | |||

| Pococke Kition inscriptions |

|

1738 | 300s BC | Cyprus | Ashmolean Museum | 33, 35 | I 11, 46 | 420,4 | 19, 23 | 13, 16 | III 35 | |

| Kition Necropolis Phoenician inscriptions |

|

1894 | 300s BC | Cyprus | British Museum | 34 | R 1206 | 420,3 | 22 | 21 | ||

| Kellia inscription |

|

1844 | Cyprus | 36 | I 47 | 420,5 | 24 | 17 | ||||

| Kition Tariffs |

|

1879 | 300s BC | Cyprus | British Museum | 37 | I 86A-B | 29 | 20 | III 33 | ||

| Idalion bilingual and Idalion Temple inscriptions |

|

1869 | 254-391 BC | Cyprus | British Museum | 38-40 | I 89-94 | 421,1-3 | 31-33 | 24-27 | III 34 | |

| Tamassos bilinguals |

|

1885 | 363 BC | Cyprus | British Museum | 41 | R 1212-1213 | 421c | 34 | 30 | ||

| Anat Athena bilingual |

|

1850 | 300s BC | Cyprus | 42 | I 95, R 1515 | 422,1 | 35 | 28 | |||

| 1893 | 200 BC | Cyprus | Louvre | 43 | R 1211 | 422,2 | 36 | 29 | III 36 | |||

| Rhodes inscriptions | Rhodes | 44-45 | III 39 | |||||||||

| Nora Stone |

|

1773 | Sardinia | Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari | 46 | I 144 | 427c | 60 | 41 | III 11 | ||

| Cippi of Melqart |

|

1694 | 100s BC | Malta | Louvre and National Museum of Archaeology, Malta | 47 | I 122 | 425f | 53 | 36 | ||

| Memphis inscription | 1900 | Memphis | Egyptian Museum | 48 | R 1, 235 | 37 | ||||||

| Abydos graffiti |

|

1868 | Abydos | in situ | 49 | I 99–110, R 1302ff. | ||||||

| Madrid inscription | unknown | 52 | R 1507 | 424 | 44 | III 37 | ||||||

| Athenian Greek-Phoenician inscriptions |

|

1795 etc | Athens, Piraeus | British Museum, Louvre, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Archaeological Museum of Piraeus | 53–60 | I 115–120, R 388, 1215 | 424,1–3, 425,1–5 | 45–52 | 32–35 | III 40–41 | ||

| Mdina steles |

|

1816 | Malta | National Museum of Archaeology, Malta | 61 | I 123A-B | 426,2 | 54 | 37 | III 21,22 | ||

| Gozo stele |

|

1855 | Malta | Gozo Museum of Archaeology | 62 | I 132 | 426,4 | 56 | 38 | |||

| Lilybaeum stele |

|

1882 | Sicily | Regional Archeological Museum Antonio Salinas | 63 | I 138 | 57 | |||||

|

1877 | 200 BC | Sardinia | Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari | 64 | I 139 | 427a | 58 | 39 | |||

| Giardino Birocchi inscription |

|

Sardinia | Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari | 65 | ||||||||

| Pauli Gerrei trilingual inscription | 1861 | Sardinia | Turin Archaeology Museum | 66 | I 143 | 427b | 59 | 40 | ||||

|

1870 | Sardinia | Museo nazionale archeologico ed etnografico G. A. Sanna | 67 | I 158 | 62 | ||||||

| Sardinia | 68 | R 1216 | ||||||||||

| Marseille Tariff |

|

1844 | 300s BC | Marseille | Musée d'archéologie méditerranéenne | 69 | I 165 | 428 | 63 | 42 | ||

| Avignon Punic inscription |

|

1897 | Avignon | Musée d'archéologie méditerranéenne | 70 | R 360 | 64 | III 18 | ||||

| Douïmès medallion |

|

1894 | 700 BCE | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 73 | I 6057, R 5 | 429,1 | 70 | |||

| Carthage Tariff |

|

1858 | 300 BC | Carthage | British Museum | 74 | I 167 | 429b | 66 | 43 | ||

| Carthage | 75 | I 3916 | ||||||||||

|

1872 | 300 BC | Carthage | lost | 76 | I 166 | 430,3 | 67 | 44 | |||

| Carthage | 77 | I 3921 | ||||||||||

|

Carthage | 78 | I 3778 | |||||||||

|

Carthage | 79 | I 3785 | |||||||||

| 1871 | Carthage | British Museum | 80 | I 175 | 430,4 | 68 | 46 | |||||

|

1898 | 200 BC | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 81 | I 3914 | 69 | 45 | ||||

|

1881 | Carthage | Turin Archaeology Museum | 82 | I 176 | 71 | ||||||

| 1873 | Carthage | 83 | I 177 | 430,6 | 72 | 47 | ||||||

| 1860 | Carthage | British Museum | 84 | I 178 | 430,7 | 73 | ||||||

|

Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 85 | I 184 | 74 | |||||||

|

1874 | Carthage | 86 | I 264 | 76 | |||||||

|

Carthage | 87 | I 221 | 80 | ||||||||

|

Carthage | 88 | I 1885 | 83 | ||||||||

| Punic Tabella Defixionis |

|

1899 | 200 BC | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 89 | I 6068, R 18, 1590 | 85 | 50 | |||

| 1904 | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 90 | I 5953, R 537 | 87 | |||||||

| 1899 | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 91 | I 5991, R 1227 | 88 | |||||||

| 1902 | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 92 | I 5948, R 768 | 89 | |||||||

|

1905 | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 93 | I 5950, R 553 | 90 | ||||||

|

Carthage | 94 | I 2992 | |||||||||

| Carthage | 95 | R 786, 1854 | ||||||||||

| Carthage | 96 | I 5988, R 183, 1600 | ||||||||||

| Euting Hadrumetum inscriptions |

|

1867 | Sousse | 97–98 | 432,1–3 | 91–92 | ||||||

| Punic-Libyan Inscription |

|

1631 | Dougga | British Museum | 100 | |||||||

| Lazare Costa inscriptions |

|

1875 | 300-200BCE | Constantine | 102–105 | R 327, 334, 339, 1544 | 433,8 and 434,10 | 94–99 | 51 | |||

| 1894 | Remada | 117 | 435b | 101 | ||||||||

| Breviglieri | 118 | R 662 | ||||||||||

| Bourgade inscriptions |

|

1852 | Carthage and wider Tunisia | 133–135 | 436,3–12 | |||||||

| Baal Hammon inscription |

|

1908 | Bir Bouregba | 137 | R 942, 1858 | |||||||

| Bou Arada | 140 | R 679 | ||||||||||

|

1873 | Henchir Brigitta | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 142 | 435,2 | 53 | ||||||

| Maktar and Mididi inscriptions |

|

1890s | Maktar and Mididi | 145–158 | R 161–181, 2221 | 436,11 | 59a-c | |||||

|

1873 | Altiburus | Louvre | 159 | 437a | 55 | ||||||

|

1870s | Cherchell | 161 | 439,2 | 57 | |||||||

| Guelma inscriptions |

|

1843 | Guelma | Louvre | 166–169 | 437 | 58 | |||||

| Sant'Antioco bilingual |

|

1881 | Sardinia | Museo archeologico comunale Ferruccio Barreca | 172 | I 149 | 434,1 | 100 | ||||

| Mesha Stele |

|

1868 | Dhiban | Louvre | 181 | 415f | 1 | 1 | I 16 | |||

| Gezer calendar |

|

1908 | Gezer | Museum of the Ancient Orient | 182 | R 1201 | I 1 | |||||

| Samaria Ostraca |

|

1910 | Sebastia | Museum of the Ancient Orient | 183–188 | I 2–3 | ||||||

| Nimrud ivory inscriptions |

|

1961 | Nimrud | I 6 | ||||||||

| Siloam inscription | 1880 | Jerusalem | Museum of the Ancient Orient | 189 | 3 | 2 | I 7 | |||||

| Ophel ostracon |

|

1924 | Jerusalem | Rockefeller Museum | 190 | I 9 | ||||||

| Shebna inscription | 1870 | Shebna | British Museum | 191 | I 8 | |||||||

| Lachish letters |

|

1935 | Tel Lachish | British Museum and Israel Museum | 192–199 | I 12 | ||||||

| Yavne-Yam ostracon |

|

1960 | Mesad Hashavyahu | Israel Museum | 200 | I 10 | ||||||

|

1948-50 | Tel Qasile | I 4 | |||||||||

| 1956 | 800s BC | Tel Hazor | I 5 | |||||||||

| 1952 | 600s BC | Wadi Murabba'at | I 11 | |||||||||

|

1960s | c.600 BC | Tel Arad | I 13 | ||||||||

| 1956-59 | 700s BC | Al Jib | I 14 | |||||||||

|

1961 | 400s BC | Khirbet Beit Lei | I 15 | ||||||||

| Melqart stele |

|

1939 | Bureij | National Museum of Aleppo | 201 | II 1 | ||||||

| Stele of Zakkur |

|

1903 | Tell Afis | Louvre | 202 | II 5 | ||||||

| Hama graffiti | 1931–38 | Hama | 203–213 | II 6 I-V | ||||||||

| Hadad Statue |

|

1890 | 700s BC | Sam'al | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 214 | 440-2 | 61 | II 13 | |||

| Panamuwa II inscription |

|

1888 | 730s BC | Sam'al | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 215 | 442 | 62 | II 14 | |||

| Bar-Rakib inscriptions |

|

1891 | 730s BC | Sam'al | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin and Museum of the Ancient Orient | 216–221 | 443, 444 | 63 | II 15–17 | |||

| Sefire steles |

|

1930–56 | As-Safira | National Museum of Damascus and National Museum of Beirut | 222–224, 227 | II 8–9, 22 | ||||||

| Neirab steles |

|

1891 | 600s BC | Al-Nayrab | Louvre | 225–226 | 445 | 64–65 | II 18–19 | |||

| Tayma stones |

|

1878–84 | 300s–400s BC | Tayma | Louvre | 228–230 | II 113–115 | 447,1–3 | 69–70 | II 30 | ||

| Tell Halaf inscription |

|

1933 | Tell Halaf | destroyed | 231 | II 10 | ||||||

| Arslan Tash ivory inscription |

|

1931 | Arslan Tash | Louvre | 232 | II 2 | ||||||

| Assur ostracon |

|

1903-13 | Assur | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 233 | II 20 | ||||||

| Kesecek Köyü inscription |

|

1915 | Kesecek Köyü | Peabody Museum of Natural History | 258 | II 33 | ||||||

| Gözne Boundary Stone |

|

1907 | Gözne | 259 | II 34 | |||||||

| Sardis bilingual inscription |

|

1912 | 394 BC | Sardis | İzmir Archaeological Museum | 260 | ||||||

| Sarıaydın inscription |

|

1892 | 400 BC | Sarıaydın | in situ | 261 | 446a | 68 | II 35 | |||

| Limyra bilingual | 1840 | Limyra | 262 | II 109 | 446b | |||||||

| Abydos lion weight |

|

1860 | 500 BC | Abydos (Hellespont) | British Museum | 263 | II 108 | 446c | 67 | |||

| Adon Papyrus |

|

1942 | Saqqara | Egyptian Museum | 266 | II 21 | ||||||

| Saqqara Aramaic Stele |

|

1877 | 482 BC | Saqqara | destroyed | 267 | II 122 | 448a1 | 71 | II 23 | ||

| Serapeum Offering Table |

|

1855 | 400 BC | Saqqara | Louvre | 268 | II 123 | 448a2 | 72 | |||

| Carpentras Stela |

|

1704 | Carpentras | Bibliothèque Inguimbertine | 269 | II 141 | 448b1 | 75 | II 24 | |||

| Elephantine papyri and ostraca |

|

300s BC | Elephantine | Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin | 270–271 | II 137–139 | 73–74 | II 26 | ||||

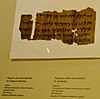

| Hermopolis Aramaic papyri |

|

1936 | 400s BC | Hermopolis | Cairo University Archaeological Museum | II 27 | ||||||

| Padua Aramaic papyri |

|

1936 | 400s BC | unknown | Musei Civici di Padova | II 28 | ||||||

| Abydos Aramaic papyrus |

|

1964 | 400s BC | unknown | National Archaeological Museum of Madrid | II 29 | ||||||

| Blacas papyri |

|

Saqqara | British Museum | II 145 | 76 | |||||||

| Ankh-Hapy stele |

|

1860 | 525–404 BCE | unknown | Vatican Museums | 272 | II 142 | 448b2 | II 7 | |||

| Aramaic Inscription of Taxila |

|

1915 | Taxila | Taxila Museum | 273 | |||||||

| Stele of Serapeitis |

|

1940 | Armazi | Georgian National Museum | 276 | |||||||

| Pyrgi Tablets |

|

1964 | Pyrgi | National Etruscan Museum | 277 | III 42 | ||||||

| Bahadırlı | 278 | II 36 | ||||||||||

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription |

|

1958 | Chil Zena | National Museum of Afghanistan | 279 | |||||||

| Baalshillem Temple Boy |

|

1963–64 | Sidon | National Museum of Beirut | 281 | III 29 | ||||||

| Ekron Royal Dedicatory Inscription |

|

1996 | Tel Miqne | Israel Museum | 286 | |||||||

| Çebel Ires Daǧı inscription |

|

1980 | Çebel Ires Daǧı | Alanya Archaeological Museum | 287 | |||||||

| Tekke Bowl Inscription (Knossos) | Crete | 291 | ||||||||||

| Hellenistic Greek-Phoenician bilingual | Kos | 292 | ||||||||||

| Demetrias inscription | Demetrias | 293 | ||||||||||

| Seville statue of Astarte |

|

1960-62 | 700 BCE | Seville | Archeological Museum of Seville | 294 | III 16 | |||||

| Carthage | 302 | I 5510 | ||||||||||

| Aedilian inscription |

|

1964 | Carthage | Carthage National Museum | 303 | |||||||

| El-Kerak Inscription |

|

1958 | Al-Karak | Jordan Archaeological Museum | 306 | I 17 | ||||||

| Amman Citadel Inscription |

|

1961 | Amman | Jordan Archaeological Museum | 307 | |||||||

| Tel Siran inscription | 1972 | Amman | Jordan Archaeological Museum | 308 | ||||||||

| Hadad-yith'i bilingual inscription |

|

1979 | Tell Fekheriye | National Museum of Damascus | 309 | |||||||

| Tel Dan Stele |

|

1993 | Tel Dan | Israel Museum | 310 | |||||||

| Deir Alla Inscription |

|

1967 | Deir Alla | Jordan Archaeological Museum | 312 | |||||||

| Daskyleion steles |

|

1965 | Dascylium | Museum of the Ancient Orient | 318 | II 37 | ||||||

| Letoon trilingual |

|

1973 | Xanthos | Fethiye Museum | 319 | |||||||

| Assyrian lion weights |

|

1845 | Nimrud | British Museum | II 1–14 | |||||||

| Çineköy inscription |

|

1997 | Çine, Yüreğir | Adana Archaeology Museum | [28] | |||||||

| Kuttamuwa stele |

|

2008 | Sam'al | Gaziantep Archaeology Museum | [29] | |||||||

| Ataruz altar inscriptions | 2010 | c. 800 BCE | Khirbat Ataruz | [30] | ||||||||

| Ishbaal Inscription |

|

2012 | 1020–980 BCE | Khirbet Qeiyafa | [31] | |||||||

| Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon |

|

2009 | c. 1000 BCE | Khirbet Qeiyafa | [32] | |||||||

| Hashub Inscription |

|

1957 | 400s BCE | Tel Zeton | Old Jaffa Museum of Antiquities | [33] | ||||||

Bibliography[]

- Röllig, Wolfgang. The Phoenician Language: Remarks on the Present State of Research. Atti del I Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici. pp. 375–385.

2, Rom 1983

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology" (PDF). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter. 427: 209–266. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

Alas, all these were either late or Punic, and came from Cyprus, from the ruins of Kition, from Malta, Sardinia, Athens, and Carthage, but not yet from the Phoenician homeland. The first Phoenician text as such was found as late as 1855, the Eshmunazor sarcophagus inscription from Sidon.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Turner, William Wadden (1855-07-03). The Sidon Inscription. p. 259.

Its interest is greater both on this account and as being the first inscription properly so-called that has yet been found in Phoenicia proper, which had previously furnished only some coins and an inscribed gem. It is also the longest inscription hitherto discovered, that of Marseilles—which approaches it the nearest in the form of its characters, the purity of its language, and its extent — consisting of but 21 lines and fragments of lines.

- ^ Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften. Worvort zur 1. Auflage, p.XI. 1961.

Seit dem Erscheinen von Mark Lidzbarskis "Handbuch der Nordsemitischen Epigraphik" (1898) und G. A. Cooke's "Text-Book of North-Semitic Inscriptions" (1903) ist es bis zum gegenwärtigen Zeitpunkt nicht wieder unternommen worden, das nordwestsemitische In schriftenmaterial gesammelt und kommentiert herauszugeben, um es Forschern und Stu denten zugänglich zu machen.... Um diesem Desideratum mit Rücksicht auf die Bedürfnisse von Forschung und Lehre abzu helfen, legen wir hiermit unter dem Titel "Kanaanäische und aramäische Inschriften" (KAI) eine Auswahl aus dem gesamten Bestände der einschlägigen Texte vor

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mark Woolmer (ed.). Phoenician: A Companion to Ancient Phoenicia. p. 4.

Altogether, the known Phoenician texts number nearly seven thousand. The majority of these were collected in three volumes constituting the first part of the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum (CIS), begun in 1867 under the editorial direction of the famous French scholar Ernest Renan (1823–1892), continued by J.-B. Chabot and concluded in 1962 by James G. Février. The CIS corpus includes 176 "Phoenician" inscriptions and 5982 "Punic" inscriptions (see below on these labels).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parker, Heather Dana Davis; Rollston, Christopher A. (2019). "9". In Hamidović, D.; Clivaz, C.; Savant, S. (eds.). Teaching Epigraphy in the Digital Age. Ancient Manuscripts in Digital Culture: Visualisation, Data Mining, Communication. 3. Alessandra Marguerat. LEIDEN; BOSTON: Brill. pp. 189–216. ISBN 9789004346734. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvrxk44t.14.

Of course, Donner and Röllig's three-volume handbook entitled KAI has been the gold standard for five decades now

- ^ Suder, Robert W. (1984). Hebrew Inscriptions: A Classified Bibliography. Susquehanna University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-941664-01-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Doak, Brian R. (2019-08-26). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-049934-1.

Most estimates place it at around ten thousand texts. Texts that are either formulaic or extremely short constitute the vast majority of the evidence.

- ^ KAUFMAN, S. (1986). The Pitfalls of Typology: On the Early History of the Alphabet. Hebrew Union College Annual, 57, 1–14. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23507690

- ^ McCarter Jr., P. Kyle (1 January 1991). "The Dialect of the Deir Alla Texts". In Jacob Hoftijzer and Gerrit Van der Kooij (ed.). The Balaam Text from Deir ʻAlla Re-evaluated: Proceedings of the International Symposium Held at Leiden, 21–24 August 1989. BRILL. pp. 87–. ISBN 90-04-09317-6.

It may be appropriate to observe at this point that students of the Northwest Semitic languages seem to be becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the usefulness of the Canaanite-Aramaic distinction for categorizing features found in texts from the Persian Period and earlier. A careful reevaluation of the binary organization of the Northwest Semitic family seems now to be underway. The study of the Deir 'Alla texts is one of the principal things prompting this reevaluation, and this may be counted as one of the very positive results of our work on these texts… the evidence of the Zakkur inscription is crucial, because it shows that the breakdown is not along Aramaic-Canaanite lines. Instead, the Deir 'Alla dialect sides with Hebrew, Moabite, and the language spoken by Zakkur (the dialect of Hamath or neighboring Lu’ath) against Phoenician and the majority of Old Aramaic dialects.

- ^ KAUFMAN, Stephen A., 1985, THE CLASSIFICATION OF THE NORTH WEST SEMITIC DIALECTS OF THE BIBLICAL PERIOD AND SOME IMPLICATIONS THEREOF. Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies, 41–57. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23529398: "The very term "Canaanite" is meaningful only vis-a-vis something else – i.e. Aramaic, and, as we shall see, each new epigraphic discovery of the early first millennium seems to contribute further evidence that the division between Canaanite and Aramaic cannot be traced back any distance into the second millennium and that the term "Canaanite," in a linguistic as opposed to an ethnic sense, is irrelevant for the Late Bronze Age. Ugaritic is a rather peripheral member of the Late Bronze Age proto-Canaanite-Aramaic dialect continuum, a dead-end branch of NW Semitic, without known descendants. Our inability to reach a universally acceptable decision on the classification of Ugaritic is by no means due only to our less than total knowledge of the language. As witnessed by the case of the Ethiopian dialects studied by Hetzron, even when we do have access to relatively complete information, classification is by no means a certain thing. How much more so, then, in the case of dialects attached in a few short, broken inscriptions! The dialect of ancient Samal has been the parade example of such a case within the NW Semitic realm. Friedrich argued long and hard for its independent status; of late, however, a consensus seems to have developed that Samalian is Aramaic, albeit of an unusual variety. The achievement of such a consensus is due in no small part to the ongoing recognition of the dialectal diversity within Aramaic at periods much earlier than previously considered, a recognition largely due to the work of our main speaker, Prof. J.C. Greenfield. When we tum to the dialect of the language of the plaster texts from Deir 'Alla, however, scholarly agreement is much less easy to perceive. The texts were published as Aramaic, or at least Aramaic with a question mark, a classification to which other scholars have lent their support. The savants of Jerusalem, on the other hand, seem to be agreed that the language of Deir 'Alla is Canaanite – perhaps even Ammonite. Now frankly I have never been much interested in classification. My own approach has always been rather open-ended. If a new language appears in Gilead in the 8th century or so, looks somewhat like Aramaic to its North, Ammonite and Moabite to its South, and Hebrew to its West (that is to say: it looks exactly like any rational person would expect it to look like) and is clearly neither ancestor nor immediate descendant of any other known NW Semitic language that we know, why not simply say it is Gileadite and be done with it? Anyone can look at a map and see that Deir 'Alla is closer to Rabbat Ammon than it is to Damascus, Samaria or Jerusalem, but that doesn't a priori make it Ammonite. Why must we try to squeeze new evidence into cubbyholes designed on the basis of old evidence?"

- ^ Garr, W. Randall (2004). "The Dialectal Continuum of Syria-Palestine". Dialect Geography of Syria-Palestine, 1000-586 B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-57506-091-0.

- ^ Huehnergard, John; Pat-El, Na’ama (2005). The Semitic Languages. Oxon: Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 0415057671.

- ^ Gibson, J. C. L. (30 October 1975). Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions: II. Aramaic Inscriptions: Including Inscriptions in the Dialect of Zenjirli. OUP Oxford. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-813186-1.

The Carpentras stele: The famous funerary stele (CIS ii 141) was the first Syrian Semitic inscr. to become known in Europe, being discovered in the early 18 cent.; it measures 0.35 m high by 0.33m broad and is housed in a museum at Carpentras in southern France.

- ^ Daniels, Peter T. (31 March 2020). "The Decipherment of Ancient Near Eastern Languages". In Rebecca Hasselbach-Andee (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-119-19329-6.

Barthélemy was not done. On 13 November 1761, he interpreted the inscription on the Carpentras stela (KAI 269), again going letter by letter, but the only indication he gives of how he arrived at their values is that they were similar to the other Phoenician letters that were by now well known… He includes a list of roots as realized in various languages – and also shows that Coptic, which he conjectured was the continuation of the earlier language of the hieroglyphs, shares a variety of grammatical features with the languages listed above. The name "Semitic" for those languages lay two decades in the future, and the group "Aramaic," which from the list includes Syriac, Chaldaean [Jewish Aramaic], and Palmyrene, as well as the Carpentras stela, seems to have been named only about 1810 though it was recognized somewhat earlier (Daniels 1991)

- ^ Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology" (PDF). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter. 427: 209–266. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-08. Quote: "Nearly two hundred years later the repertory of Phoenician-Punic epigraphy counts about 10.000 inscriptions from throughout the Mediterranean and its environs."

- ^ Rollig, 1983

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rollig, 1983, "The Phoenician-Punic vocabulary attested to date amounts to some 668 words, some of which occur frequently. Among these are 321 hapax legomena and about 15 foreign or loan words. In comparison with Hebrew with around 7000–8000 words and 1500 hapax legomena (8), the number is remarkable."

- ^ Ullendorff, E. (1971). Is Biblical Hebrew a Language?. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 34. University of London. pp. 241–255. JSTOR 612690.

- ^ Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology" (PDF). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. 427: 210 and 257. ISBN 978-3-11-026612-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

Soon thereafter, at the end of the 17th century, the abovementioned Ignazio di Costanzo was the first to report a Phoenician inscription and to consciously recognize Phoenician characters proper... And just as the Melitensis prima inscription played a prominent part as the first-ever published Phoenician inscription... and remained the number-one-inscription in the Monumenta (fig. 8), it now became the specimen of authentic Phoenician script par excellence... The Melitensis prima inscription of Marsa Scirocco (Marsaxlokk) had its lasting prominence as the palaeographic benchmark for the assumed, or rather deduced "classical" Phoenician ("echtphönikische") script.

- ^ Millard, A. (1993), Reviewed Work: Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions. Corpus and Concordance by G. I. Davies, M. N. A. Bockmuehl, D. R. de Lacey, A. J. Poulter, The Journal of Theological Studies, 44(1), new series, 216–219: "...every identifiable Hebrew inscription dated before 200 BC... First ostraca, graffiti, and marks are grouped by provenance. This section contains more than five hundred items, over half of them ink-written ostraca, individual letters, receipts, memoranda, and writing exercises. The other inscriptions are names scratched on pots, scribbles of various sorts, which include couplets on the walls of tombs near Hebron, and letters serving as fitters' marks on ivories from Samaria.... The seals and seal impressions are set in the numerical sequence of Diringer and Vattioni (100.001–100.438). The pace of discovery since F. Vattioni issued his last valuable list (Ί sigilli ebraici III', AnnaliAnnali dell'Istituto Universitario Orientate di Napoli 38 (1978), 227—54) means the last seal entered by Davies is 100.900. The actual number of Hebrew seals and impressions is less than 900 because of the omission of those identified as non-Hebrew which previous lists counted. A further reduction follows when duplicate seal impressions from different sites are combined, as cross references in the entries suggest... The Corpus ends with 'Royal Stamps' (105.001-025, the Imlk stamps), '"Judah" and "Jerusalem" Stamps and Coins' (106.001-052), 'Other Official Stamps' (107.001), 'Inscribed Weights' (108.001-056) and 'Inscribed Measures' (109.001,002).... most seals have no known provenance (they probably come from burials)... Even if the 900 seals are reduced by as much as one third, 600 seals is still a very high total for the small states of Israel and Judah, and most come from Judah. It is about double the number of seals known inscribed in Aramaic, a language written over a far wider area by officials of great empires as well as by private persons.

- ^ Graham I. Davies; J. K. Aitken (2004). Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions: Corpus and Concordance. Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-521-82999-1.

This sequel to my Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions includes mainly inscriptions (about 750 of them) which have been published in the past ten years. The aim has been to cover all publications to the end of 2000. A relatively small number of the texts included here were published earlier but were missed in the preparation of AHI. The large number of new texts is not due, for the most part, to fresh discoveries (or, regrettably, to the publication of a number of inscriptions that were found in excavations before 1990), but to the publication of items held in private collections and museums.

- ^ Avigad, N. (1953). The Epitaph of a Royal Steward from Siloam Village. Israel Exploration Journal, 3(3), 137–152: "The inscription discussed here is, in the words of its discoverer, the first 'authentic specimen of Hebrew monumental epigraphy of the period of the Kings of Judah', for it was discovered ten years before the Siloam tunnel inscription. Now, after its decipherment, we may add that it is (after the Moabite Stone and the Siloam tunnel inscription) the third longest monumental inscription in Hebrew and the first known text of a Hebrew sepulchral inscription from the pre-Exilic period."

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, 1899, Archaeological Researches In Palestine 1873–1874, Vol 1, p.305: "I may observe, by the way, that the discovery of these two texts was made long before that of the inscription in the tunnel, and therefore, though people in general do not seem to recognise this fact, it was the first which enabled us to behold an authentic specimen of Hebrew monumental epigraphy of the period of the Kings of Judah."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology" (PDF). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter. 427: 240. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

Basically, its core consists of the comprehensive edition, or re-edition of 70 Phoenician and some more non-Phoenician inscriptions... However, just to note the advances made in the nineteenth century, it is noteworthy that Gesenius' precursor Hamaker, in his Miscellanea Phoenicia of 1828, had only 13 inscriptions at his disposal. On the other hand only 30 years later the amount of Phoenician inscribed monuments had grown so enormously that Schröder in his compendium Die phönizische Sprache. Entwurf einer Grammatik nebst Sprach- und Schriftproben of 1869 could state that Gesenius knew only a quarter of the material Schröder had at hand himself.

- ^ "Review of Wilhelm Gesenius's publications". The Foreign Quarterly Review. L. Scott. 1838. p. 245.

What is left consists of a few inscriptions and coins, found principally not where we should a priori anticipate, namely, at the chief cities themselves, but at their distant colonies... even now there are not altogether more than about eighty inscriptions and sixty coins, and those moreover scattered through the different museums of Europe.

- ^ Rollig, 1983, "This increase of textual material can be easily appreciated when one looks at the first independent grammar of Phoenician , P.SCHRODER'S Die phonizische Sprache Entuurf einer Grammatik, Halle 1869, which appeared just over 110 years ago. There on pp. 47–72 all the texts known at the time are listed — 332 of them. Today, if we look at CIS Pars I, the incompleteness of which we scarcely need mention, we find 6068 texts."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bevan, A. (1904). NORTH-SEMITIC INSCRIPTIONS. The Journal of Theological Studies, 5(18), 281–284. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23949814

- ^ Tekoglu, R. & Lemaire, A. (2000). La bilingue royale louvito-phénicienne de Çineköy. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des inscriptions, et belleslettres, année 2000, 960–1006. Important additions to the interpretation of the Luwian version were made in I. Yakubovich, Phoenician and Luwian in Early Iron Age Cilicia, Anatolian Studies 65 (2015), pp. 40–44

- ^ Schloen, J., & Fink, A. (2009). New Excavations at Zincirli Höyük in Turkey (Ancient Samʾal) and the Discovery of an Inscribed Mortuary Stele. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, (356), 1–13. Retrieved September 16, 2020

- ^ Adam L. Bean (2018). "An inscribed altar from the Khirbat Ataruz Moabite sanctuary". Levant. 50 (2): 211–236. doi:10.1080/00758914.2019.1619971. S2CID 199266038.

- ^ Yosef Garfinkel, Mitka R. Golub, Haggai Misgav, and Saar Ganor (2015). "The ʾIšbaʿal Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 373 (373): 217–233. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.373.0217. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.373.0217. S2CID 164971133.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Aaron Demsky (2012). "An Iron Age IIA Alphabetic Writing Exercise from Khirbet Qeiyafa". Israel Exploration Journal. Israel Exploration Society. 62 (2): 186–199. JSTOR 43855624.

- ^ Jacob Kaplan (1958). "The Excavation in Tell Abu Zeitun in 1957". Bulletin of the Israel Exploration Society (in Hebrew). Israel Exploration Society. 22 (1/2): 99. JSTOR 23730357.

- Semitic inscriptions

- Archaeological corpora

- Semitic languages

- Inscriptions by languages

- Phoenician inscriptions