Climate change vulnerability

Climate change vulnerability (or climate vulnerability or climate risk vulnerability) is an assessment of vulnerability to climate change used in discussion of society's response to climate change, for processes like climate change adaptation, evaluations of climate risk or in determining climate justice concerns. Climate vulnerability can include a wide variety of different meanings, situations and contexts in climate change research, but has been a central concept in academic research since 2005.[1] The concept was defined in the third IPCC report as "the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes".[2]: 89

Vulnerability can mainly be broken down into two major categories, economic vulnerability, based on socioeconomic factors, and geographic vulnerability. Neither are mutually exclusive. In line with system-level approach to vulnerability in the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), most scholarship uses climate vulnerability to describe communities, economic systems or geographies.[3] However, the widespread impacts of climate change have led to the use of "climate vulnerability" to describe less systemic concerns, such as individual health vulnerability, vulnerable situations or other applications beyond impacted systems, such as describing the vulnerability of individual animal species. There are several organizations and tools used by the international community and scientists to assess climate vulnerability.

Types[]

Negative impacts of climate change are those that are least capable of developing robust and comprehensive climate resiliency infrastructure and response systems. However what exactly constitutes a vulnerable community is still open to debate. The IPCC has defined vulnerability using three characteristics: the “adaptive capacity, sensitivity, and exposure” to the effects of climate change. The adaptive capacity refers to a community's capacity to create resiliency infrastructure, while the sensitivity and exposure elements are both tied to economic and geographic elements that vary widely in differing communities. There are, however, many commonalities between vulnerable communities.[4]

Vulnerability can mainly be broken down into two major categories, economic vulnerability, based on socioeconomic factors, and geographic vulnerability. Neither are mutually exclusive.

Economic vulnerability[]

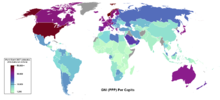

At its basic level, a community that is economically vulnerable is one that is ill-prepared for the effects of climate change because it lacks the needed financial resources. Preparing a climate resilient society will require huge[quantify] investments in infrastructure, city planning, engineering sustainable energy sources, and preparedness systems.[clarification needed] From a global perspective, it is more likely that people living at or below poverty will be affected the most by climate change and are thus the most vulnerable, because they will have the least amount of resource dollars to invest in resiliency infrastructure. They will also have the least amount of resource dollars for cleanup efforts after more frequently occurring natural climate change related disasters.[5]

Geographic vulnerability[]

A second definition of vulnerability relates to geographic vulnerability. The most geographically vulnerable locations to climate change are those that will be impacted by side effects of natural hazards, such as rising sea levels and by dramatic changes in ecosystem services, including access to food. Island nations are usually noted as more vulnerable but communities that rely heavily on a sustenance based lifestyle are also at greater risk.[6]

Vulnerable communities tend to have one or more of these characteristics:[7]

- food insecure

- water scarce

- delicate marine ecosystem

- fish dependent

- small island community

Around the world, climate change affects rural communities that heavily depend on their agriculture and natural resources for their livelihood. Increased frequency and severity of climate events disproportionately affects women, rural, dryland, and island communities.[8] This leads to more drastic changes in their lifestyles and forces them to adapt to this change. It is becoming more important for local and government agencies to create strategies to react to change and adapt infrastructure to meet the needs of those impacted. Various organizations work to create adaptation, mitigation, and resilience plans that will help rural and at risk communities around the world that depend on the earth's resources to survive.[9]

Differences by region or sector[]

Vulnerability is often framed in dialogue with climate adaptation. IPCC (2007a) defined adaptation (to climate change) as "[initiatives] and measures to reduce the vulnerability of natural and human systems against actual or expected climate change effects" (p. 76).[2] Vulnerability (to climate change) was defined as "the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes" (p. 89). Different communities or systems are better prepared for adaptation in part because of their existing vulnerabilities.[2]

Regions[]

With high confidence, researchers concluded in 2001 that developing countries would tend to be more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries.[10]: 957–958 Based on then-current development trends, it was predicted that few developing countries would have the capacity to efficiently adapt to climate change. [10]: 940–941

- Africa: Africa's major economic sectors have been vulnerable to observed climate variability.[11]: 435 This vulnerability was judged to have contributed to Africa's weak adaptive capacity, resulting in Africa having high vulnerability to future climate change. It was thought likely that projected sea-level rise would increase the socio-economic vulnerability of African coastal cities.

- Asia: Climate change is expected to result in the degradation of permafrost in boreal Asia, worsening the vulnerability of climate-dependent sectors, and affecting the region's economy.[12]: 536

- Australia and New Zealand: In Australia and New Zealand, most human systems have considerable adaptive capacity. However, some Indigenous communities were judged to have low adaptive capacity.[13]: 509

- Europe: The adaptation potential of socioeconomic systems in Europe is relatively high.[14]: 643 This was attributed to Europe's high GNP, stable growth, stable population, and well-developed political, institutional, and technological support systems.

- Latin America: The adaptive capacity of socioeconomic systems in Latin America is very low, particularly in regard to extreme weather events, and that the region's vulnerability was high.[15]: 697

- Polar regions: A study in 2001 concluded that:[16]: 804–805

- within the Antarctic and Arctic, at localities where water was close to melting point, socioeconomic systems are particularly vulnerable to climate change.

- the Arctic is extremely vulnerable to climate change. It is predicted that there will be major ecological, sociological, and economic impacts in the region.

- Small islands: Small islands are particularly vulnerable to climate change.[17]: 689 Partly this was attributed to their low adaptive capacity and the high costs of adaptation in proportion to their GDP.

Systems and sectors[]

- Coasts and low-lying areas: Societal vulnerability to climate change is largely dependent on development status.[18]: 336 Developing countries lack the necessary financial resources to relocate those living in low-lying coastal zones, making them more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries. On vulnerable coasts, the costs of adapting to climate change are lower than the potential damage costs.[19]: 317

- Industry, settlements and society:

- At the scale of a large nation or region, at least in most industrialized economies, the economic value of sectors with low vulnerability to climate change greatly exceeds that of sectors with high vulnerability.[20]: 336 Additionally, the capacity of a large, complex economy to absorb climate-related impacts, is often considerable. Consequently, estimates of the aggregate damages of climate change – ignoring possible abrupt climate change – are often rather small as a percentage of economic production. On the other hand, at smaller scales, e.g., for a small country, sectors and societies might be highly vulnerable to climate change. Potential climate change impacts might therefore amount to very severe damages.

- Vulnerability to climate change depends considerably on specific geographic, sectoral and social contexts. These vulnerabilities are not reliably estimated by large-scale aggregate modelling.[21]: 359

Impacts on disadvantaged groups[]

Socio-economic disparities[]

Climate change and poverty are deeply intertwined because climate change disproportionally affects poor people in low-income communities and developing countries around the world. Those in poverty have a higher chance of experiencing the ill-effects of climate change due to the increased exposure and vulnerability.[22] Vulnerability represents the degree to which a system is susceptible to, or unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change including climate variability and extremes.[23]

Climate change highly influences health, economy, and human rights which affects environmental inequities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth National Climate Assessment Report found that low-income individuals and communities are more exposed to environmental hazards and pollution and have a harder time recovering from the impacts of climate change.[24] For example, it takes longer for low-income communities to be rebuilt after natural disasters.[25] According to the United Nations Development Programme, developing countries suffer 99% of the casualties attributable to climate change.[26]Indigenous people[]

Climate change and indigenous peoples describes how climate change disproportionately impacts indigenous peoples around the world when compared to non-indigenous peoples. These impacts are particularly felt in relation to health, environments, and communities. Some indigenous scholars of climate change argue that these disproportionately felt impacts are linked to ongoing forms of colonialism.[27] Indigenous peoples found throughout the world have strategies and traditional knowledge to adapt to climate change. These knowledge systems can be beneficial for their own community's adaptation to climate change as expressions of self-determination as well as to non-indigenous communities.

The majority of the world's biodiversity is located within indigenous territories.[28] There are over 370 million indigenous peoples[29] found across 90+ countries.[30] Approximately 22% of the planet's land is indigenous territories, with this figure varying slightly depending on how both indigeneity and land-use are defined.[31] Indigenous peoples play a crucial role as the main knowledge keepers within their communities. This knowledge includes that which relates to the maintenance of social-ecological systems.[32] The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People recognizes that indigenous people have specific knowledge, traditional practices, and cultural customs that can contribute to the proper and sustainable management of ecological resources.[33]Gender[]

Climate change and gender is a way to interpret the disparate impacts of climate change on men and women,[34] based on the social construction of gender roles and relations.[35]

Climate change increases gender inequality,[36] reduces women's ability to be financially independent,[37] and has an overall negative impact on the social and political rights of women, especially in economies that are heavily based on agriculture.[36] In many cases, gender inequality means that women are more vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change.[38] This is due to gender roles, particularly in the developing world, which means that women are often dependent on the natural environment for subsistence and income. By further limiting women's already constrained access to physical, social, political, and fiscal resources, climate change often burdens women more than men and can magnify existing gender inequality.[34][39][40][41]Tools[]

Climate vulnerability can be analyzed or evaluating using a number of processes or tools. Below are several of them. There are several organizations and tools used by the international community and scientists to assess climate vulnerability.

Assessments[]

Vulnerability assessments are done for local communities to evaluate where and how communities or systems will be vulnerable to climate change. These kinds of reports can vary widely in scope and scale-- for example the World Bank and Ministry of Economy of Fiji commissioned a report for the whole country in 2017-18[42] while the Rochester, New York commissioned a much more local report for the city in 2018.[43] Or, for example, NOAA Fisheries commissioned Climate Vulnerability assessments for marine fishers in the United States.[44]

Vulnerability assessments in Global south[]

In the Global South, the vulnerability assessment is usually developed during the process of preparing local adaptation plans for climate change or sustainable action plans.[45] The vulnerability is ascertained on an urban district or neighborhood scale. Vulnerability is also a determinant of risk and is consequently ascertained each time a risk assessment is required. In these cases, the vulnerability is expressed by an index, made up of indicators. The information that allows to measure the single indicators are already available in statistics and thematic maps, or are collected through interviews. The latter case is used on very limited territorial areas (a city, a municipality, the communities of a district). It is therefore an occasional assessment aimed at a specific event: a project, a plan.[46]

For example, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) in India published a framework for doing vulnerability assessments of communities in India.[47]

Indexes[]

Climate Vulnerability Monitor[]

This article needs to be updated. (February 2014) |

The Climate Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) is an independent global assessment of the effect of climate change on the world's populations brought together by panels of key international authorities. The Monitor was launched in December 2010 in London and Cancun to coincide with the UN Cancun Summit on climate change (COP-16).[48][49]

Developed by DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, the report is meant to serve as a new tool to assess global vulnerability to various effects of climate change within different nations.[50]

The report distills leading science and research for a clearer explanation of how and where populations are being affected by climate change today (2010) and in the near future (2030), while pointing to key actions that reduce these impacts.[51]

DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum launched the 2nd edition of the Climate Vulnerability Monitor on 26 September 2012 at the Asia Society, New York.[52]Climate Vulnerability Index[]

James Cook University is producing a vulnerability index for World Heritage Sites globally, including cultural, natural and mixed sites.[53]

Mapping[]

A systematic review published in 2019 found 84 studies focused on the use of mapping to communicate and do analysis of climate vulnerability.[54]

Vulnerability tracking[]

Climate vulnerability tracking starts identifying the relevant information, preferably open access, produced by state or international bodies at the scale of interest. Then a further effort to make the vulnerability information freely accessible to all development actors is required.[46] Vulnerability tracking has many applications. It constitutes an indicator for the monitoring and evaluation of programs and projects for resilience and adaptation to climate change. Vulnerability tracking is also a decision making tool in regional and national adaptation policies.[46]

International relations[]

Because climate vulnerability disproportionally effects countries without the economic or infrastructure of more developed countries, climate vulnerability has become an important tool in international negotiations about climate change adaptation, climate finance and other international policy making activities.

Climate Vulnerable Forum[]

The Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) is a global partnership of countries that are disproportionately affected by the consequences of global warming.[55] The forum addresses the negative effects of global warming as a result of heightened socioeconomic and environmental vulnerabilities. These countries actively seek a firm and urgent resolution to the current intensification of climate change, domestically and internationally.[56]

The CVF was formed to increase the accountability of industrialized nations for the consequences of global climate change. It also aims to exert additional pressure for action to tackle the challenge, which includes local action by countries considered susceptible.[56] Political leaders involved in this partnership are "using their status as those most vulnerable to climate change to punch far above their weight at the negotiating table".[57] The governments which founded the CVF agree to national commitments to pursue low-carbon development and carbon neutrality.[58]

Ethiopia became the first African Chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum during the CVF High-Level Climate Policy Forum held in the Senate of the Philippines in August 2016.[59]See also[]

References[]

- ^ Füssel, Hans-Martin (2005-12-01). "Vulnerability in Climate Change Research: A Comprehensive Conceptual Framework". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c IPCC (2007a). "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ "Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2012 — European Environment Agency". www.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ J.J. McCarthy, O.F. Canziani, N.A. Leary, D.J. Dokken, K.S. White (Eds.), Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ^ M.J. Collier et al. "Transitioning to resilience and sustainability in urban communities" Cities 2013. 32:21–S28

- ^ K. Hewitt (Ed.), Interpretations of Calamity for the Viewpoint of Human Ecology, Allen and Unwin, Boston (1983), pp. 231–262

- ^ Kasperson, Roger E., and Jeanne X. Kasperson. Climate change, vulnerability, and social justice. Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute, 2001.

- ^ "Climate Change". Natural Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Achieving Dryland Women's Empowerment: Environmental Resilience and Social Transformation Imperatives" (PDF). Natural Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, J. B.; et al. (2001). "Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.J. McCarthy et al. Eds.)". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Boko, M.; et al. (2007). M. L. Parry; et al. (eds.). "Africa. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. pp. 433–467. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ Lal, M.; et al. (2001). J. J. McCarthy; et al. (eds.). "Asia. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Hennessy, K.; et al. (2007). M. L. Parry; et al. (eds.). "Australia and New Zealand. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. pp. 507–540. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ Kundzewicz, Z. W.; et al. (2001). J. J. McCarthy; et al. (eds.). "Europe. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Mata, L. J.; et al. (2001). "Latin America. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [J. J. McCarthy et al. Eds.]". Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Anisimov, O.; et al. (2001). Executive Summary. In (book chapter): Polar Regions (Arctic and Antarctic). In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.J. McCarthy et al. (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: GRID-Arendal website. ISBN 978-0-521-80768-5. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Mimura, N.; et al. (2007). Executive summary. In (book chapter): Small islands. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry et al., (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Nicholls, R. J.; et al. (2007). 6.4.3 Key vulnerabilities and hotspots. In (book chapter): Coastal systems and low-lying areas. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry et al. (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Nicholls, R. J.; et al. (2007). Executive summary. In (book chapter): Coastal systems and low-lying areas. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry et al. (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Wilbanks, T. J.; et al. (2007). 7.4.1 General effects. In (book chapter): Industry, settlement and society. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry et al. (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Wilbanks, T. J.; et al. (2007). Executive summary. In (book chapter): Industry, settlement and society. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry et al. (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Rayner, S. and E.L. Malone (2001). "Climate Change, Poverty, and Intragernerational Equity: The National Leve". International Journal of Global Environment Issues. 1. I (2): 175–202. doi:10.1504/IJGENVI.2001.000977.

- ^ Smit, B, I. Burton, R.J.T. Klein, and R. Street (1999). "The Science of Adaption: A framework for Assessment". Mitigation and Adaption Stretegies for Global Change. 4 (3/4): 199–213. doi:10.1023/A:1009652531101. S2CID 17970320.

- ^ "Fourth National Climate Assessment". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019.

- ^ Chappell, Carmin (2018-11-26). "Climate change in the US will hurt poor people the most, according to a bombshell federal report". CNBC. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2007/2008: The 21st Century Climate Challenge" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Whyte, Kyle (2017). "Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene". . 55 (1): 153–162. doi:10.1215/00138282-55.1-2.153. S2CID 132153346 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Raygorodetsky, Gleb (2018-11-16). "Can indigenous land stewardship protect biodiversity?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ^ Etchart, Linda (2017-08-22). "The role of indigenous peoples in combating climate change". Palgrave Communications. 3 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.85. ISSN 2055-1045.

- ^ "Indigenous Peoples". World Bank. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- ^ Sobrevila, Claudia (2008). The role of indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation: the natural but often forgotten partners. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 5.

- ^ Green, D.; Raygorodetsky, G. (2010-05-01). "Indigenous knowledge of a changing climate". Climatic Change. 100 (2): 239–242. Bibcode:2010ClCh..100..239G. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9804-y. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 27978550.

- ^ Nations, United. "United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olsson, Lennart et al. "Livelihoods and Poverty." Archived 2014-10-28 at the Wayback Machine Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Ed. C. B. Field et al. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. 793–832. Web.(accessed October 22, 2014)

- ^ CARE. "Adaptation, Gender, and Women's Empowerment." Archived 2013-08-05 at the Wayback Machine Care International Climate Change Brief. (2010). (accessed March 18, 2013).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eastin, Joshua (2018-07-01). "Climate change and gender equality in developing states". World Development. 107: 289–305. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.021. ISSN 0305-750X.

- ^ Goli, Imaneh; Omidi Najafabadi, Maryam; Lashgarara, Farhad (2020-03-09). "Where are We Standing and Where Should We Be Going? Gender and Climate Change Adaptation Behavior". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 33 (2): 187–218. doi:10.1007/s10806-020-09822-3. ISSN 1573-322X. S2CID 216404045.

- ^ Habtezion, Senay (2013). Overview of linkages between gender and climate change. Gender and Climate Change. Asia and the Pacific. Policy Brief 1 (PDF). United Nations Development Programme.

- ^ Aboud, Georgina. "Gender and Climate Change." (2011).

- ^ Dankelman, Irene. "Climate change is not gender-neutral: realities on the ground." Public Hearing on "Women and Climate Change". (2011)

- ^ Birkmann, Joern et al."Emergent Risks and Key Vulnerabilities." Archived 2014-09-23 at the Wayback Machine Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Ed. C. B. Field et al. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. 1039–1099. Web. (accessed October 25, 2014).

- ^ "Fiji: Climate Vulnerability Assessment | GFDRR". www.gfdrr.org. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "CLIMATE VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT". City of Rochester NY.

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA (2019-09-19). "Climate Vulnerability Assessments | NOAA Fisheries". NOAA. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ Tiepolo, Maurizio (2017). "Relevance and Quality of Climate Planning for Large and Medium-Sized Cities of the Tropics". In M. Tiepolo et al. (Eds.) Revewing Local Planning to Face Climate Change in the Tropics. Cham, Springer. Green Energy and Technology: 199–226. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59096-7_10. ISBN 978-3-319-59095-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tiepolo, Maurizio; Bacci, Maurizio (2017). "Tracking Climate Change Vulnerability at Municipal Level in Haiti using Open Source Information". In M. Tiepolo et al. (Eds.), Renewing Local Planning to Face Climate Change in the Tropics. Cham, Springer: 103–131. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59096-7_6.

- ^ Satapathy, S. (September 2014). A Framework for Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments. Porsché, Ilona, Rolker, Dirk, Bhatt, Somya, Tomar, Sanjay, Nair, Sreeja, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) (Projektdokument ed.). New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-930074-0-2. OCLC 950725140.

- ^ [1] Archived December 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BCS s.c. "High Commission of the Republic of MALDIVES | President Nasheed Launches Climate Vulnerable Monitor 2010". Maldiveshighcommission.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ^ Black, Richard (2010-12-03). "BBC News - Poorer nations 'need carbon cuts', urges The Maldives". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ^ "New report: 5 million climate deaths predicted by 2020 | MNN - Mother Nature Network". MNN. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ^ "Launch of the 2nd Edition of the Climate Vulnerability Monitor". Daraint.org. 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- ^ "Home". Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI). Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ Sherbinin, Alex de; Bukvic, Anamaria; Rohat, Guillaume; Gall, Melanie; McCusker, Brent; Preston, Benjamin; Apotsos, Alex; Fish, Carolyn; Kienberger, Stefan; Muhonda, Park; Wilhelmi, Olga (2019). "Climate vulnerability mapping: A systematic review and future prospects". WIREs Climate Change. 10 (5): e600. doi:10.1002/wcc.600. ISSN 1757-7799.

- ^ "About".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Climate Vulnerable Forum Declaration adopted - DARA".

- ^ "Nasheed asks: "Will our culture be allowed to die out?"". ENDS Copenhagen Blog. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014.

- ^ "CVF Declaration" (PDF).

- ^ "Philippines and Ethiopia Lead Global Climate Coalition to Speed Development - Climate Vulnerable Forum". Climate Vulnerable Forum. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2016-09-22.>

- Climate change adaptation

- Risk analysis

- Vulnerability

- Ecology