Danish phonology

The phonology of Danish is similar to that of the other closely related Scandinavian languages, Swedish and Norwegian, but it also has distinct features setting it apart. For example, Danish has a suprasegmental feature known as stød which is a kind of laryngeal phonation that is used phonemically. It also exhibits extensive lenition of plosives, which is noticeably more common than in the neighboring languages. Because of that and a few other things, spoken Danish is rather hard to understand for Norwegians and Swedes, although they can easily read it.

Consonants[]

Danish has at least 17 consonant phonemes:

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | f | s | (ɕ) | h | |||

| Approximant | v | ð | j | (w) | r | ||

| Lateral | l |

| Phone | Phoneme | Morphophoneme | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syllable- initial |

Syllable- final | ||

| [m] | /m/ | |m| | |

| [n] | /n/ | |n| | |

| [ŋ] | /ŋ/ | N/A | |nɡ|, |ŋ|,[a] |n|[b] |

| [pʰ] | /p/ | |p| | N/A |

| [tsʰ] | /t/ | |t| | N/A |

| [kʰ] | /k/ | |k| | N/A |

| [p] | /b/ | |b| | |p, b| |

| [t] | /d/ | |d| | |t| |

| [k] | /ɡ/ | |ɡ| | |k| |

| [f] | /f/ | |f| | |

| [s] | /s/ | |s| | |

| [ɕ] | /sj/ | |sj|[c] | |

| [h] | /h/ | |h| | N/A |

| [ʋ] | /v/ | |v| | N/A |

| [ð] | /ð/ | N/A | |d| |

| [j] | /j/ | |j| | |j, ɡ| |

| [w] | /v/ | N/A | |v, ɡ| |

| [ʁ] | /r/ | |r| | N/A |

| [ɐ̯] | /r/ | N/A | |r| |

| [l] | /l/ | |l| | |

/p, t, k, h/ occur only syllable-initially and [ŋ, ð, w] only syllable-finally.[2][3] [ɕ] is phonemically /sj/ and [w] is the syllable-final allophone of /v/.[4] [w] also occurs syllable-initially in English loans, along with [ɹ], but syllable-initial [w] is in free variation with [v] and these are not considered part of the phonological inventory of Danish.[5]

/ŋ/ occurs only before short vowels and stems morphophonologically, in native words, from |nɡ| or |n| preceding |k| and, in French loans, from a distinct |ŋ|. Beyond morphological boundaries, [ŋ] may also appear as the result of an optional assimilation of /n/ before /k, ɡ/.[6]

/n, t, d, s, l/ are apical alveolar [n̺, t̺s̺ʰ, t̺, s̺, l̺],[7] although some speakers realize /s/ dentally ([s̪]).[8][9]

/p, t, k/ are voiceless aspirated, with /t/ also affricated: [pʰ, tsʰ, kʰ].[10] The affricate [tsʰ] is often transcribed with ⟨tˢ⟩. In some varieties of standard Danish (but not the Copenhagen dialect), /t/ is just aspirated, without the affrication.[11]

/b, d, ɡ/ are voiceless unaspirated [p, t, k].[12] In syllable codas, weak, partial voicing may accompany them especially when between voiced sounds.[13] Utterance-final /b, d, ɡ/ may be realized as [pʰ, t(s)ʰ, kʰ], particularly in distinct speech.[14] Intervocalic /d/ may be realized as a voiced flap [ɾ], as in nordisk [ˈnoɐ̯ɾisk] 'Nordic'.[15][16]

/h/ is only weakly fricated.[17] Between vowels, it is often voiced [ɦ].[18]

/v/ can be a voiced fricative [v], but is most often a voiced approximant [ʋ].[19]

/ð/ – the so-called "soft d" (Danish: blødt d) – is a velarized laminal alveolar approximant [ð̠˕ˠ].[20][21][22] It is acoustically similar to the cardinal vowels [ɯ] and [ɨ].[21] It is commonly perceived by non-native speakers of Danish as [l].[23][21] Very rarely, /ð/ can be realized as a fricative.[22]

Syllable-initially, /r/ is a voiced uvular fricative [ʁ] or, more commonly, an approximant [ʁ̞].[24] According to Nina Grønnum, the fricative variant is voiceless [χ].[25] Its precise place of articulation has been described as pharyngeal,[26] or more broadly, as "supra-pharyngeal".[27] When emphasizing a word, word-initial /r/ may be realized as a voiced uvular fricative trill [ʀ̝].[15] In syllable-final position, /r/ is realized as [ɐ̯].[2]

The alveolar realization [r] of /r/ is very rare. According to Torp (2001), it occurs in some varieties of Jutlandic dialect, and only for some speakers (mostly the elderly). The alveolar realization is considered non-standard, even in classical opera singing – it is probably the only European language in which this is the case.[28] According to Basbøll (2005), it occurs (or used to occur until recently) in very old forms of certain conservative dialects in Northern Jutland and Bornholm.[29]

/l, j, r/ are voiceless [l̥, ç~ɕ, χ] after /p, t, k/, where the aspiration is realized as devoicing of the following consonant,[30] so that /tj/ is normally realized as an alveolo-palatal affricate [tɕ].[31]

A voiced velar continuant [ɣ] occurred distinctively in older Standard Danish. Some older speakers still use it in high register, most often as an approximant [ɣ˕].[32][33] It corresponds to [w], after back vowels and /r/, and to /j/, after front vowels and /l/, in contemporary Standard Danish.[32]

/j/ is elided after /iː, yː/, and possibly also after /eː, øː/, and less commonly after /ɛː, aː/. Similarly, /v/ is elided after /uː/, and possibly also after /oː/, and less commonly after /ɔː/.[34]

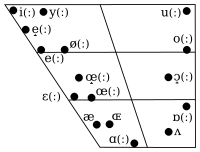

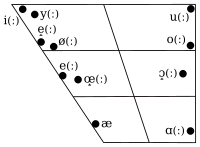

Vowels[]

Modern Standard Danish has around 20 different vowel qualities. These vowels are shown below in a narrow transcription.

/ə/ and /ɐ/ occur only in unstressed syllables and thus can only be short. Long vowels may have stød,[citation needed] thus making it possible to distinguish 30 different vowels in stressed syllables.[citation needed] However, vowel length[citation needed] and stød are most likely features of the syllable rather than of the vowel.

The 26 vowel phonemes of Standard Danish (14 short and 12 long) correspond to 21 morphophonemes (11 short and 10 long).

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː | ||

| Close-mid | e | eː | ø | øː | ə | o | oː | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | œ | œː | ɐ | ɔ | ɔː | |

| Open | a | aː | ɑ | ɑː | ɒ | ɒː | ||

| Morpho- phoneme |

Tautosyllabic environment |

Phoneme | Phone | Narrow tran- scription |

Example | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After | Before | ||||||

| |i| | /i/ | [i] | [i] | mis | |||

| |iː| | /iː/ | [iː] | [iː] | mile | |||

| |e| | /e/ | [e̝] | [e̝] | list | |||

| |r| | [ɛ̝] | [ɛ̝] | brist | ||||

| |eː| | /eː/ | [e̝ː] | [e̝ː] | mele | |||

| |r| | /ɛː/ | [ɛ̝ː] | [ɛ̝ː~ɛ̝j] | grene | |||

| |ɛ| | /ɛ/ | [e] | [e] | læst | |||

| |r| | [ɛ] | [ɛ] | bær | ||||

| |r| | |∅, D| | /ɛ/ or /ɑ/ | [æ~ɑ] | [a~ɑ̈] | række | [ɑ] in innovative varieties.[37] | |

| /ɑ/ | [ɑ] | [ɑ̈] | kræft | ||||

| |ɛː| | /ɛː/ | [eː] | [eː] | mæle | |||

| |r| | [eː~ɛː] | [eː~ɛː] | bære | [ɛː] in innovative varieties.[38] | |||

| |r| | [ɛ̝ː] | [ɛ̝ː~ɛ̝j] | kræse | ||||

| |d| | /aː/ or /ɑː/ | [æː~ɑː] | [æː~ɑ̈ː] | græde | [ɑː] in innovative varieties.[39] | ||

| |a| | ≠ |r| | |A| | /a/ | [æ] | [æ] | malle | |

| /ɑ/ | [ɑ] | [ɑ̈] | takke | ||||

| |ar| | |#| | var | Only in a handful of words.[40] | ||||

| /ɑː/ | [ɑː] | [ɑ̈ː] | arne | ||||

| |aː| | /aː/ | [ɛː] | [ɛː] | male | |||

| |r| | /ɑː/ | [ɑː] | [ɑ̈ː] | trane | |||

| |aːr| | har | ||||||

| |y| | /y/ | [y] | [y] | lyt | |||

| |yː| | /yː/ | [yː] | [yː] | kyle | |||

| |ø| | /ø/ | [ø] | [ø] | kys | |||

| |r| | ≠ |v, j, ɡ| | [œ̝~œ] | [œ̝~œ] | grynt | [œ] in innovative varieties. | ||

| |v| | /œ/ | [ɶ] | [ɶ̝] | drøv | [41] | ||

| |j, ɡ| | /ɔ/ | [ʌ] | [ɒ̽] | tøj | |||

| |øː| | /øː/ | [øː] | [øː] | køle | |||

| |r| | [œ̝ː~œː] | [œ̝ː~œː] | røbe | [œː] in innovative varieties. | |||

| |œ| | /œ/ | [œ̝] | [œ̝] | høns | |||

| |r| | [œ] | [œ] | gør | ||||

| |r| | [ɶ] | [ɶ̝] | grøn | ||||

| |œː| | /œː/ | [œ̝ː] | [œ̝ː] | høne | Rare.[42] | ||

| |r| | [œː] | [œː] | gøre | ||||

| |u| | /u/ | [u] | [u] | guld | |||

| |r| | /u/ | [u~o] | [u~o̝] | brusk | [o] in innovative varieties.[43] | ||

| |uː| | /uː/ | [uː] | [uː] | mule | |||

| |r| | /uː/ or /oː/ | [uː~oː] | [uː~o̝ː] | ruse | [oː] in innovative varieties.[43] | ||

| |o| | |∅, r| | /o/ | [o] | [o̝] | sort ('black') | ||

| [ɔ̝] | [ɔ̽] | ost ('cheese') | |||||

| |oː| | /oː/ | [oː] | [o̝ː] | mole | |||

| |ɔ| | /ɔ/ | [ʌ] | [ɒ̽] | måtte | |||

| |ɔr| | |#| | /ɒ/ | [ɒ] | [ɒ̝] | vor | Only in a handful of words.[40] | |

| /ɒː/ | [ɒː] | [ɒ̝ː] | morse | ||||

| |ɔːr| | tårne | ||||||

| |ɔː| | /ɔː/ | [ɔ̝ː] | [ɔ̽ː] | måle | |||

| |ə| | /ə/ | [ə] | [ə] | hoppe | |||

| |ər| | /ɐ/ | [ɐ] | [ɒ̽] | fatter | |||

| |rə| | ture | After long vowels.[44] | |||||

| |rər| | turer | ||||||

| |jə| | /jə/ | [ɪ] | [ɪ] | veje | See § Schwa-assimilation. | ||

| |ɡə| | jage | ||||||

| |və| | /və/ | [ʊ] | [ʊ] | have | |||

| |əd| | /əð/ | [ð̩] | [ð̩˕˗ˠ] | måned | |||

| |də| | /ðə/ | bade | |||||

| |əl| | /əl/ | [l̩] | [l̩] | gammel | |||

| |lə| | /lə/ | tale | |||||

| |nə| | /nə/ | [n̩] | [n̩] | håne | |||

| |ən| | /ən/ | hesten | |||||

| [m̩] | [m̩] | hoppen | |||||

| [ŋ̍] | [ŋ̍] | pakken | |||||

The three way distinction in front rounded vowels /y ø œ/ is upheld only before nasals, e.g. /syns sønˀs sœns/ synes, synds, søns ('seems', 'sin's', 'son's').

/a/ and /aː/ on the one hand and /ɑ/ and /ɑː/ on the other are largely in complementary distribution. However, a two-phoneme interpretation can be justified with reference to the unexpected vowel quality in words like andre /ˈɑndrɐ/ 'others' or anderledes /ˈɑnɐˌleːðəs/ 'different', and an increasing number of loanwords.[45]

Some phonemes and phones that only occur in unstressed position often merge with full phonemes and phones:[46]

- [ʊ] with [o], leading to a variable merger of /və/ and /o/ (the former can be [wə] or [wʊ] instead, in which case no merger takes place).

- /ɐ/ with /ɔ/. According to Basbøll (2005), these sounds are usually merged, the main difference being the greater variability in the realizations of /ɐ/, which only occurs in unstressed position. In the narrow phonetic transcriptions of Grønnum (2005) and Brink et al. (1991), the two sounds are treated as identical.[47][48]

The vowel system is unstable, and according to a study by Ejstrup & Hansen (2004), the contemporary spoken language might be experiencing a merger of several of these vowels. The following vowel pairs may be merged by some speakers (only vowels not adjacent to |r| were analyzed):[49]

- [øː] with [œ̝ː] (11 out of 18 speakers)

- [ø] with [œ̝] (7 out of 18)

- [e̝ː] with [eː] (5 out of 18)

- [e̝] with [e] (5 out of 18)

- [o] with [ɔ̝] (4 out of 18)

- [eː] with [ɛː] (3 out of 18)

- [o:] with [ɔ̝:] (2 out of 18)

- [u:] with [o:] (1 out of 18)

Schwa-assimilation[]

In addition to /ɐ/, which stems from the fusion of |ər|, |rə|, or |rər|, /ə/ assimilates to adjacent sonorants in a variety of ways:[50]

- /ə/ assimilates to preceding long vowels: /ˈdiːə/ → [ˈtiːi] die 'nurse', /ˈduːə/ → [ˈtuːu] due 'pigeon'.[51]

- /jə/ after a long vowel other than /iː, yː/ and /və/ after a long vowel other than /uː/ become monophthongs [ɪ, ʊ]: /ˈlɛːjə/ → [ˈleːɪ] læge 'doctor', /ˈlɔːvə/ → [ˈlɔ̝ːʊ] låge 'gate'.[50] In innovative varieties, the vowels may become shorter: [ˈlejɪ], [ˈlɔ̝wʊ].[52]

- A sonorant consonant (/ð, l, m, n, ŋ/) and /ə/, in either order, become a syllabic consonant [ð̩, l̩, m̩, n̩, ŋ̍].[53]

- It is longer after a short vowel than after a long one: /ˈbaːðə/ → [ˈpæːð̩] bade 'bathe', /ˈhuːlə/ → [ˈhuːl̩] hule 'cave', /ˈsbiðə/ → [ˈspiðð̩] spidde 'spear', /ˈkulə/ → [ˈkʰull̩] kulde 'cold'.[54]

- When /ə/ is placed between two sonorant consonants, the second becomes syllabic: /ˈsaðəl/ → [ˈsæðl̩] saddel 'saddle', /ˈhyləð/ → [ˈhylð̩] hyldet 'praised'.[54]

- The place of a syllabic nasal (/ən/) assimilates to that of the preceding consonant: /ˈlɑbən/ → [ˈlɑpm̩] lappen 'the patch', /ˈlɑɡən/ → [ˈlɑkŋ̍] lakken 'varnishes'.[55]

In casual speech, /ə/ may also be elided after an obstruent. If that occurs after a long vowel, the syllable with the elided /ə/ may be retained by lengthening the vowel preceding the consonant: /ˈhɔːbə/ → [ˈhɔ̝ː(ɔ̝)p] håbe 'hope'.[54]

Glottal stop insertion[]

A word-initial vowel may be preceded by a glottal stop [ʔ] when preceded by a vowel. This is known as sprængansats.[56]

Prosody[]

Stress[]

Unlike the neighboring Scandinavian languages Swedish and Norwegian, the prosody of Danish does not have phonemic pitch. Stress is phonemic and distinguishes words like billigst [ˈpilist] ('cheapest') and bilist [piˈlist] ('car driver'). In syntactic phrases, verbs lose their stress (and stød, if any) with an object without a definite or indefinite article: e.g. ˈJens ˈspiser et ˈbrød [ˈjens ˈspiˀsɐ e̝t ˈpʁœ̝ðˀ] ('Jens eats a loaf') ~ ˈJens spiser ˈbrød [ˈjens spisɐ ˈpʁœ̝ðˀ] ('Jens eats bread'). In names, only the surname is stressed, e.g. [johæn̩luiːsə ˈhɑjˌpɛɐ̯ˀ] Johanne Luise Heiberg.[57]

Stød[]

In a number of words with stress on the final syllable, long vowels and sonorants may exhibit a prosodic feature called stød ('thrust').[58] Acoustically, vowels with stød tend to be a little shorter[58] and feature creaky voice.[59] Historically, this feature operated as a redundant aspect of stress on monosyllabic words that had either a long vowel or final voiced consonant. Since the creation of new monosyllabic words, this association with monosyllables is no longer as strong. Some other tendencies include:

- Polysyllabic words with the nominal definite suffix -et may exhibit stød[58]

- Polysyllabic loanwords with final stress on either a long vowel or a vowel with a final sonorant typically feature stød[58]

Diphthongs with an underlying long vowel always have stød.[60]

Text sample[]

The sample text is an indistinct reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun.

Orthographic version[]

Nordenvinden og solen kom engang i strid om, hvem af dem der var den stærkeste.[57]

Broad phonetic transcription[]

[ˈnoɐ̯ɐnˌve̝nˀn̩ ʌ ˈsoˀl̩n kʰʌm e̝ŋˈkɑŋˀ i ˈstʁiðˀ ˈʌmˀ ˈvemˀ ˈæ pm̩ tɑ vɑ tn̩ ˈstɛɐ̯kəstə][57]

References[]

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 75–6, 547.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basbøll (2005), p. 64.

- ^ Grønnum (1998), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 64–5.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 63.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 75.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 60–3, 131.

- ^ Thorborg (2003), p. 80. The author states that /s/ is pronounced with "the tip of the tongue right behind upper teeth, but without touching them." This is confirmed by the accompanying image.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 144. Only this author mentions both alveolar and dental realizations.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), pp. 120, 303–5.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 303.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), pp. 303–5.

- ^ Goblirsch (2018), pp. 134–5, citing Fischer-Jørgensen (1952) and Abrahams (1949, pp. 116–21, 228–30).

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 213.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grønnum (2005), p. 157.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 126.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 61–2.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 125.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 27.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 59, 63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grønnum (2003), p. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 144.

- ^ Haberland (1994), p. 320.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 62, 66.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 62.

- ^ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 323.

- ^ Grønnum (1998), p. 99.

- ^ Torp (2001), p. 78.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 218.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 65–6.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 148.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basbøll (2005), pp. 211–2.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 123.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 296.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 45–7, 52, 57–9, 71, 546–7.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), pp. 36–7, 59–61, 287–92, 420–1.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 45.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 149.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 285.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basbøll (2005), p. 154.

- ^ Brink et al. (1991), p. 87.

- ^ Brink et al. (1991), p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Basbøll (2005), p. 150.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 72, 81.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), pp. 50–1.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 58.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 419; both sounds are transcribed as [ʌ˖˕˒].

- ^ Brink et al. (1991), p. 86, using ɔ in the Dania transcription.

- ^ Ejstrup & Hansen (2004).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grønnum (2005), pp. 186–7.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 186.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 269.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), pp. 301–2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grønnum (2005), p. 187.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 302.

- ^ Grønnum, Nina (2 February 2009). "sprængansats". Den Store Danske. lex.dk. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grønnum (1998), p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Haberland (1994), p. 318.

- ^ Basbøll (2005), p. 83.

- ^ Grønnum (2005), p. 294.

Bibliography[]

- Abrahams, Henrik (1949), Études phonétiques sur les tendances évolutives des occlusives germaniques, Aarhus University Press

- Allan, Robin; Holmes, Philip; Lundskær-Nielsen, Tom (2011) [First published 2000], Danish: An Essential Grammar (2nd ed.), Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-87800-2

- Basbøll, Hans (2005), The Phonology of Danish, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-151968-5

- Brink, Lars; Lund, Jørn; Heger, Steffen; Jørgensen, J. Normann (1991), Den Store Danske Udtaleordbog, Munksgaard, ISBN 87-16-06649-9

- Ejstrup, Michael; Hansen, Gert Foget (2004), Vowels in regional variants of Danish (PDF), Stockholm: Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University

- Fischer-Jørgensen, Eli (1952), "Om stemtheds assimilation", in Bach, H.; et al. (eds.), Festskrift til L. L. Hammerich, Copenhagen: G. E. C. Gad, pp. 116–129

- Fischer-Jørgensen, Eli (1972), "Formant Frequencies of Long and Short Danish Vowels", in Scherabon Firchow, Evelyn; Grimstad, Kaaren; Hasselmo, Nils; O'Neil, Wayne A. (eds.), Studies for Einar Haugen: Presented by Friends and Colleagues, The Hague: Mouton, pp. 189–213, doi:10.1515/9783110879131-017, ISBN 978-90-279-2338-7

- Goblirsch, Kurt (2018), Gemination, Lenition, and Vowel Lengthening: On the History of Quantity in Germanic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-03450-1

- Grønnum, Nina (1998), "Illustrations of the IPA: Danish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28 (1 & 2): 99–105, doi:10.1017/s0025100300006290

- Grønnum, Nina (2003), "Why are the Danes so hard to understand?" (PDF), in Jacobsen, Henrik Galberg; Bleses, Dorthe; Madsen, Thomas O.; Thomsen, Pia (eds.), Take Danish – for instance: linguistic studies in honour of Hans Basbøll, presented on the occasion of his 60th birthday, Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, pp. 119–130

- Grønnum, Nina (2005), Fonetik og fonologi, Almen og Dansk (3rd ed.), Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, ISBN 87-500-3865-6

- Haberland, Hartmut (1994), "Danish", in König, Ekkehard; van der Auwera, Johan (eds.), The Germanic Languages, Routledge, pp. 313–348, ISBN 1317799585

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The Sounds of the World's Languages, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4

- Ladefoged, Peter; Johnson, Keith (2010), A Course in Phonetics (6th ed.), Boston, Massachusetts: Wadsworth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4282-3126-9

- Maddieson, Ian; Spajić, Siniša; Sands, Bonny; Ladefoged, Peter (1993), "Phonetic structures of Dahalo", in Maddieson, Ian (ed.), UCLA working papers in phonetics: Fieldwork studies of targeted languages, 84, Los Angeles: The UCLA Phonetics Laboratory Group, pp. 25–65

- Thorborg, Lisbet (2003), Dansk udtale – øvebog, Forlaget Synope, ISBN 87-988509-4-6

- Torp, Arne (2001), "Retroflex consonants and dorsal /r/: mutually excluding innovations? On the diffusion of dorsal /r/ in Scandinavian", in van de Velde, Hans; van Hout, Roeland (eds.), 'r-atics, Brussels: Etudes & Travaux, pp. 75–90, ISSN 0777-3692

- Uldall, Hans Jørgen (1933), A Danish Phonetic Reader, The London phonetic readers, London: University of London Press

Further reading[]

- Basbøll, Hans (1985), "Stød in modern Danish", Folia Linguistica, 19 (1–2): 1–50, doi:10.1515/flin.1985.19.1-2.1

- Brink, Lars; Lund, Jørn (1975), Dansk rigsmål 1-2, Copenhagen: Gyldendal

- Brink, Lars; Lund, Jørn (1974), Udtaleforskelle i Danmark, Copenhagen: Gjellerup, ISBN 978-8713019465

- Grønnum, Nina (1992), The groundworks of Danish intonation, Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, ISBN 978-8772891699

- Grønnum, Nina (1996), "Danish vowels – scratching the recent surface in a phonological experiment" (PDF), Acta Linguistica Hafniensia, 28: 5–63, doi:10.1080/03740463.1996.10416062

- Grønnum, Nina (1998), "Intonation in Danish", in Hirst, Daniel; Di Cristo, Albert (eds.), Intonation Systems: A Survey of Twenty Languages, ISBN 0-521-39513-5

- Grønnum, Nina (2007), Rødgrød med fløde – En lille bog om dansk fonetik, Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, ISBN 978-87-500-3918-1

- Heger, Steffen (1981), Sprog og lyd – Elementær dansk fonetik (2nd ed.), Copenhagen: Gjellerup, ISBN 87-500-3089-2

- Lundskær-Nielsen, Tom; Barnes, Michael; Lindskog, Annika (2005), Introduction to Scandinavian phonetics: Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, Alfabeta, ISBN 978-8763600095

- Molbæk Hansen, Peter (1990), Udtaleordbog, Copenhagen: Gyldendal, ISBN 978-87-02-05895-6

External links[]

- Danish language

- Germanic phonologies