Judiciary of Italy

Politics of Italy |

|---|

|

|

The Judiciary of Italy is a system of courts that interpret and apply the law in the Italian Republic. In Italy, judges are public officials and, since they exercise one of the sovereign powers of the State, only Italian citizens are eligible for judgeship. In order to become a judge, applicants must obtain a degree of higher education as well as pass written and oral examinations. However, most training and experience is gained through the judicial organization itself. The potential candidates then work their way up from the bottom through promotions.[1]

Italy's independent judiciary enjoys special constitutional protection from the executive branch. Once appointed, judges serve for life and cannot be removed without specific disciplinary proceedings conducted in due process before the High Council of the Judiciary.[2]

The Ministry of Justice handles the administration of courts and judiciary, including paying salaries and constructing new courthouses. The Ministry of Justice and that of the Infrastructures fund and the Ministry of Justice and that of the Interiors administer the prison system. Lastly, the Ministry of Justice receives and processes applications for presidential pardons and proposes legislation dealing with matters of civil or criminal justice.[3]

The structure of the Italian judiciary is divided into three tiers: inferior courts of original and general jurisdiction; intermediate appellate courts which hear cases on appeal from lower courts; courts of last resort which hear appeals from lower appellate courts on the interpretation of law.[4]

The constitutional principles[]

The Constitution of the Italian Republic affirms some important general principles, such as art. 25 reiterating the importance of the natural judge and art. 102 where it is stated that the discipline of the judicial function is subject to the rules of the legal system as well as the prohibition of establishing new extraordinary judges or special judges.[5]

Furthermore, according to the provisions of art. 104 of the Constitution the judiciary constitutes an autonomous and independent order from any other power;[6] therefore each magistrate, both judge and prosecutor, is also irremovable by law, unless he gives his consent or failing that only for the reasons and with the defense guarantees provided for by the Italian judicial system.[7]

The self-governing body of the judiciary is the High Council of the Judiciary, a institution of constitutional importance, chaired by the President of the Italian Republic.[8] This body is entitled, pursuant to art. 105 of the Constitution, in order to guarantee the autonomy and independence of the judiciary, recruitment, assignments and transfers, promotions and disciplinary measures towards judges.[8]

The legal status[]

General provisions[]

The Italian judicial authority directly has the judicial police;[9] ordinary magistrates are distinguished only by their functions and are irremovable, that is, they cannot be dispensed from service or transferred to another location without prior ruling by the High Council of the Judiciary.[10] Magistrates in education offices as well as those of the public prosecutor are given the opportunity to carry weapons for self-defense without a license.[11]

Components[]

Career magistrates - called togates - are divided into:[12]

- ordinary: ordinary civil and criminal jurisdiction;

- civilians

- criminals

- administratives: Council of State, regional administrative courts, which have jurisdiction for the protection of legitimate interests in relation to the public administration and, in particular matters indicated by law (exclusive jurisdiction), also of subjective rights;

- accountants: Court of Audit, competence in the matter of compensation for tax damage, caused by those who manage and operate with public finances;

- fiscals: Provincial Commissions and, by appeal, in Regional Commissions, jurisdiction over disputes relating to any type of tax or tax.

Furthermore, art. 106 of the Italian Constitution establishes that the office of councilor of cassation can also be entrusted, for outstanding merits, to university professors in legal matters as well as to lawyers with at least fifteen years of practice who are registered in the rolls for higher jurisdictions.[13]

The Italian honorary judiciary, which supports the career judiciary, is composed of the honorary justice of the peace, the honorary deputy prosecutor and the honorary court judge.[14] The adjective "honorary" indicates that he carries out his duties in a non-professional manner, since he usually exercises jurisdiction for a fixed period of time without receiving remuneration, but only compensation for the activity carried out.[15] Finally, there is the Italian military judiciary, a competence relating to military crimes committed by members belonging to the Italian armed forces.[12]

Responsibility[]

The magistrates are liable in criminal, civil and disciplinary terms for the actions they have committed to the detriment of citizens in the exercise of their functions; the principle of public liability of judges has its basis in art. 28 of the Constitution, according to which the officials and employees of the State and public bodies are directly responsible, according to criminal, civil and administrative laws, for acts committed in violation of rights.[16] In such cases it extends to the State and public bodies.[16]

Personnel[]

Recruitment[]

To become magistrates, both ordinary toga and belonging to the Italian honorary magistracy, it is necessary to pass a public competition organized by the Ministry of Justice. For ordinary magistrates, in addition to obtaining a law degree, having obtained the title of lawyer and having a forensic service of at least five years and, if registered in the professional register of lawyers, not having incurred disciplinary sanctions; however, some alternative requirements are envisaged for obtaining the forensic qualification, namely:[17]

- achievement of a diploma issued by the Specialization Schools for Legal Professions;

- achievement of a Doctor of Philosophy in law, or a specialization diploma from post-graduate specialization schools;

- be university lecturers in legal matters without incurring disciplinary sanctions;

- have been part of the Italian honorary magistracy for at least 6 years without demerit, without having been revoked and who have not incurred disciplinary sanctions;

- be employees of the Italian administration with the qualification of belonging to a position of public belonging to C (according to the provisions of the sector to which the public belongs), belonging to the category of at least five years of seniority in the qualification, and not having incurred disciplinary sanctions;

- have undergone an internship at the judicial offices[18] or have carried out a professional internship for eighteen months at the State Attorney's Office;[19]

- be administrative and accounting magistrates;

- be state prosecutors who have not incurred disciplinary sanctions.

In the case of professional magistrates, it is a competition for exams and the announcement is issued every two years, it consists of a written test, consisting in the preparation of three documents concerning civil law, criminal law and administrative law and a substantial oral one. in an interdisciplinary interview on the following subjects::[20]

- Roman law;

- civil law;

- civil procedure;

- criminal law;

- administrative law;

- constitutional right;

- tax law;

- commercial law;

- bankruptcy law;

- labor law;

- social security law;

- European Union law;

- public international law and private international law;

- elements of legal information technology and the Italian judicial system;

- interview on a foreign language, indicated by the candidate when applying for participation in the competition, chosen from: English, Spanish, French or German.

The winners of the competition acquire the qualification of "ordinary internship magistrate", as required by the Mastella reform of 2007, which also made some changes in terms of access requirements, such as the elimination of the age limit. However, the declaration of non-eligibility for previously held competitions, if achieved 3 times on the expiry date of the deadline for submitting the application, will make it impossible to be admitted to further selections.[21]

Training and updating[]

The following training activities are provided for ordinary magistrates:[22]

- "initial training" (for internship magistrates);

- "permanent training" for professional judges (implemented nationally and locally)

- training for office managers;

- "permanent training" for honorary magistrates (implemented nationally and locally);

- "International training".

The "lifelong learning", previously carried out by the CSM (IX Commission)[23], from autumn 2012 gradually passed to the Higher School of the Judiciary. The inauguration of the training activities at the single site of Villa Castel Pulci in Scandicci (Florence) took place on 15 October 2012.[24]

Judicial stream[]

The Italian judiciary is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the civil law, the criminal law and the administrative law in legal cases.

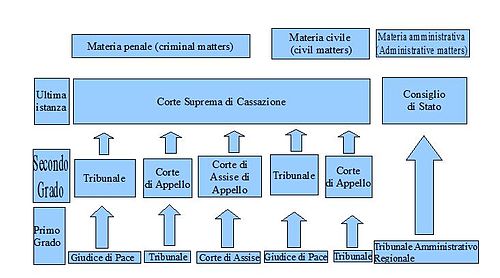

The structure of the Italian judiciary is divided into three tiers (gradi, sing. grado), primo grado ("first tier"), secondo grado ("second tier") and ultima istanza ("last resort") also called terzo grado ("third tier"): Inferior courts of original and general jurisdiction; Intermediate appellate courts which hear cases on appeal from lower courts; Courts of last resort which hear appeals from lower appellate courts on the interpretation of law.[4]

Giudice di pace[]

The giudice di pace ("Justice of the peace") is the court of original jurisdiction for less significant civil matters. The court replaced the old preture ("Praetor Courts") and the giudice conciliatore ("judge of conciliation") in 1991.[25]

Tribunale[]

The tribunale ("tribunal") is the court of general jurisdiction for civil matters. Here, litigants are statutorily required to be represented by an Italian barrister, or avvocato. It can be composed of one judge or of three judges, according to the importance of the case.[8] When acting as Appellate Court for the Justice of the Peace, it is always monocratico (composed of only one Judge).[8]

Divisions and Specialized Divisions[]

- Giudice del lLavoro ("labor tribunal"): hears disputes and suits between employers and employees (apart from cases dealt with in administrative courts, see below). A single judge presides over cases in the giudice del lavoro tribunal.[26]

- Sezione specializzata agraria ("land estate court"): the specialized section that hears all agrarian controversies. Cases in this court are heard by three professional Judges and two lay Judges.

- Tribunale per i minorenni ("Family Proceedings Court"): the specialized section that hears all cases concerning minors, such as adoptions or emancipations; it is presided over by two professional Judges and two lay Judges.

Corte d'appello[]

The Corte d'appello ("Court of Appeal") has jurisdiction to retry the cases heard by the Tribunale as a Court of first instance and is divided into three or more divisions: labor, civil, and criminal.

Corte Suprema di Cassazione[]

The Corte Suprema di Cassazione ("Supreme Court of Cassation") is the highest court of appeal or court of last resort in Italy. It has its seat in the Palace of Justice, Rome. The Court of Cassation also ensures the correct application of law in the inferior and appeal courts and resolves disputes as to which lower court (penal, civil, administrative, military) has jurisdiction to hear a given case.

Corte d'Assise[]

The Corte d'Assise ("Court of Assizes") has jurisdiction to try all crimes carrying a maximum penalty of 24 years in prison or more. These are the most serious crimes, such as terrorism and murder. Also slavery, killing a consenting human being, and helping a person to commit suicide are serious crimes that are tried by this court. Penalties imposed by the court can include life sentences (ergastolo).

Corte d'assise e d'appello[]

The Corte d'assise e d'appello ("Court of Assize Appeal") judges following an appeal against the sentences issued in the first instance by the assize court or by the judge of the preliminary hearing who has judged in the forms of the abbreviated judgment on crimes whose knowledge is normally devolved to the court of assizes. An appeal is made to the Supreme Court of Cassation against his sentences. The Court of Assize Appeal is made up of two professional judges and six popular judges. Its constituency coincides with that of the court of appeal, of which it can be considered a specialized section.

Tribunale amministrativo regionale[]

The tribunale amministrativo regionale ("Regional administrative court") is competent to judge appeals, brought against administrative acts, by subjects who consider themselves harmed (in a way that does not comply with the legal system) in their own legitimate interest. These are administrative judges of first instance, whose sentences are appealable before the Council of State. For the same reason, it is the only type of special judiciary to provide for only two degrees of judgment.

Consiglio di Stato[]

The Consiglio di Stato ("Council of State") is, in the Italian legal system, a body of constitutional significance. Provided for by Article 100 of the Constitution, which places it among the auxiliary organs of the Government, it is a judicial body, and is also the highest special administrative judge, in a position of third party with respect to the Italian public administration, pursuant to Article 103 of the Constitution.

References[]

- ^ Guarnieri, Carlo (1997). "The judiciary in the Italian political crisis". West European Politics. 20: 157–175. doi:10.1080/01402389708425179.

- ^ "Autonomia ed indipendenza della magistratura" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Riforma della giustizia penale: contesto, obiettivi e linee di fondo della "legge Cartabia"" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Il ricorso per cassazione. L'impugnazione per i soli vizi di applicazione della legge. Il terzo grado di Giudizio" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 102 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 104 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Circolare CSM 30 novembre 1993, n. 15098" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Consiglio superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022. Cite error: The named reference "treccani" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Art. 109 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Coatitizione della Repubblica Italiana Art. 107 - Inamovibilità dei magistrati" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 73 R.D. 6 maggio 1940 n. 635" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Come diventare magistrato: percorso di studi, concorso, opportunità" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "La costituzione italiana - Articolo 106" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Riforma organica della magistratura onoraria e altre disposizioni sui giudici di pace" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "le figure della magistratura onoraria" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "La Costituzione - Articolo 28" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Descrizione del concorso sul sito del Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 73 del decreto legge 21 giugno 2013, n. 69 - convertito in legge 9 agosto 2013, n. 98" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 50 decreto legge 24 giugno 2014, n. 90 convertito in legge 11 agosto 2014, n. 114" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Come funziona concorso in magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Art. 1 paragraph 3 law 30 July 2007 n. 111.

- ^ "Sito della Scuola superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Competenze della IX Commissione sul sito del Consiglio superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Scuola superiore della magistratura, "Inizio delle attività didattiche"" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Legge n. 374/1991" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "A cosa serve il giudice del lavoro?" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- Judiciary of Italy

- Government of Italy

- Italian constitutional institutions