Crime in Italy

Crime in Italy ranks from low to moderate, but is present in several forms, such as murder, sexual violence, corruption, and several more. However, Italy is most notorious for its organised crime groups, present all over the world, known as the Italian Mafia.[1] These crimes are combated by the spectrum of Italian law enforcement agencies, composed of Carabinieri, Polizia, and Guardia di Finanza. Italy holds the 8th position in Europe in regards to the number of law enforcement per 100 thousand people with 453 units, compared to the European average which is 335.[2] Although crime covers the Italian Peninsula, Italy holds some of the lowest toll of rapes and murders in the European Union. Out of 128 countries, Italy is the 40th safest country in the world.[3]

Crime by type[]

Murder[]

In 2012, national murder rate was about 0.9 per 100,000 population, one of the lower rates in Western Europe.[4] There were a total of 530 murders in Italy in 2012.[4]

Homicides in Italy have decreased by 20% in the last ten years, with 0.6 murders per 100.000 people.[5] In fact in 2017, 357 individuals were murdered in Italy, a number that decreased even further between August 2018 and July 2019, where 307 murders were registered. [6][7]

In 2020, there were a total of only 271 murders, lower than 315 murders the previous year, and much lower than the 1,916 thirty years ago in 1991.[8]

Organized crime[]

Many worldwide crime organizations originated in Italy, and their influence is widespread in Italian society, directly affecting a reported 22% of citizens and 14.6% of Italy's Gross Domestic Product.[9] Public figures such as former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi have been charged with association in organized criminal acts.[10] War against organized crime caused hundreds of murders, including judges (Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino) and lawyers (like Roberto Calvi).

There are several separate criminal organizations controlling territory and business activities: Sicilian Cosa Nostra, Campanian Camorra, Calabrese 'Ndrangheta, and Apulian Sacra Corona Unita. More than 13 million people are involved into crime web. Their business involvement is on a European and global scale.[11] Particularly in Naples an unusual high homicide rate and several drug addicted people have qualified the town as the most dangerous in Western Europe.[9][12]

Businesses, entrepreneurs, shopkeepers, and craftsmen in these regions are expected to pay protection money. There is rarely any possibility of escaping payment, and those not complying find their business premises and lives at risk. People not able to meet demands might find their business partly or completely taken over by organized crime.[11]

In 2009, organized crime in Italy generated $189 billion in revenue.[13]

In 2020, there were only 28 murders related to the mafia, compared to an average of 527 murders between 1988 and 1992.[8]

Sexual violence[]

Italy has a lower per capita rate of rape than most of the advanced Western countries in the European Union.[14]

According to Police authorities data, the rate of sexual assaults per 100,000 inhabitants is significantly higher in the Northern region than in the Southern ones. In 2009, Lombardia and Emilia Romagna were the regions with the highest rate of sexual offences per 100.000 inhabitants (9.7); followed by Trentino Alto Adige and Tuscany (9.5); Piedmont and Liguria (8.6); Umbria (8.4). In this respect, all major Southern regions like Sicily (6.8); Calabria (6.5); Apulia (6.2); Campania (6,0) were the safest in the national territory, with the only exception of Friuli Venezia Giulia (5.1) in the North.[15]

Fraud[]

Fraud is a major contributor to Italy's crime rate, with some level of fraud appearing in all sectors of the economy since the country's founding in 1861. Notable cases of financial fraud include the collapse of Parmalat in the early years of the 21st century, and the Lockheed bribery scandal in the 1970s.

Insurance fraud also dramatically increases the cost of insurance in Italy, with 115,646 incidents of fraudulent claims in 2001 alone, with 3.28 percent of all claims in 2002 ascertained to have involved fraud. The percentage rose above ten percent in some of the southern provinces.[16]

State employees have been perceived to have such a high rate of absenteeism, often feigning illness, that in 2008 the government introduced a law to harshly prosecute civil servants who are found to be making fraudulent claims about their health.[17] Fraudulent claims of ill health are not confined to state employees, with some physicians often willing to receive bribes to certify non-existent conditions so that citizens may receive disability benefits. A case was revealed in 2010 where in one quartiere of Naples alone, 400 people were found to be claiming mental illness although healthy.[18]

Corruption[]

Political corruption remains a major problem in Italy, particularly in Southern Italy including Calabria, parts of Campania and Sicily where corruption perception is at a high level.[19][20] Political parties are ranked as the most corrupt institution in Italy, closely followed by public officials and Parliament, according to Transparency International's Global Corruption Barometer 2013.[21]

[]

Italy is considered one of the drug portals to Europe thanks to its geolocation and omnipresence of organised crime groups.[22] Substantial amounts of illegal drugs are smuggled through the country with the goal of reaching other European nations. These narcotics are exported from drug producing regions principally via maritime route but also via air and land. Areas such as South America, specifically Columbia produce and supply cocaine, Southeast Asia and Afghanistan principally supply heroin, whereas north-western and south-eastern Europe, Morocco and Albania cultivate and deliver cannabis.[22] The drugs are bought and distributed both in Italy and in the rest of Europe by organised crime groups.[22]

Italians are not solely transporters and smugglers of narcotics, they are also consumers. While using is not a crime itself, possession for personal use is.[23]

The general population survey on drugs conducted in 2017 deduced that Italians within the ages of 15 and 64, in the course of their life, had, at least once, made use of psychoactive substances, with 1 in 10 using in the past year.[24] Cannabis is the most used drug within the population, with an estimated 1.1 % using it daily, whereas, 20.9% of young adults have used in the last year.

Use of cocaine and other psychoactive drugs is reported to be lower within the peninsula, where it has been recorded that 1.7% of young adults have used cocaine in the past year. Moreover, Italy is considered one of the EU countries with the highest number of high risk opioid use, with high use of off label drugs.[25][24]

The number of drug law offenders in 2019 was 73 804.[26] In 2017, over 35,000 people were convicted by the police for drug related crimes, this number decreased in October 2018 to about 23,600 people. Furthermore, in 2015, a third of the aggregate of convicts was in prison due to drug related crimes. In fact, Italy held the record amongst the 47 member states of the European Council for drug related convictions. [27][28]

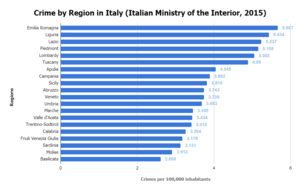

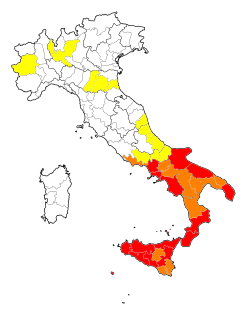

By location[]

Levels of crime are unevenly spread throughout the peninsula.

Southern Italy[]

Southern Italy as a whole demonstrates lower crime rates than northern Italy across the board -violent crime, sexual assault, petty crime are highest in northern cities. [29]https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criminalit%C3%A0_in_Italia There is corruption and Mafia-related activities in Naples, Sicily and Calabria but also in northern cities. Southern Italy remains highly rural.

Naples[]

Waste management problems affected Naples; Italian media have attributed the city's waste disposal issues to the activity of the Camorra organised crime network.[30] In 2007, Silvio Berlusconi's government held senior meetings in Naples to demonstrate their intention to solve these problems.[31] In December 2009 "waste emergency" officially finished.[32] In June 2012, allegations of blackmail, extortion and illicit contract tendering emerged in relation to the city's waste management issues.[33][34]

Central and Northern Italy[]

Most regions in the center and north may be considered calmer and more organized, but they do demonstrate higher levels of criminal activity. Statistics put Milan, Florence, Turin, Genoa, Rome, and Rimini as the most dangerous for crime. §[35] Regions such as Marche, Tuscany, Umbria in the centre and Piedmont, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Liguria and Friuli Venezia Giulia present relatively low criminal indicators compared to other western countries. But even in the north and center levels of crime are unequally spread. Cities such as Turin, Milan, Bologna, Genoa in the North frequently suffer a wide diversity of frequent offences ranging from extensive drug trade, homicides, etc.[citation needed]

Rome[]

The capital Rome presents medium to high levels of crime. But many areas of the Roman periphery are extensively dilapidated and crime-ridden to a much larger extent than northern and central European counterparts. Shantytowns on the outskirts of the city housing more than 4,000 people are focuses of elevated criminal activity.[citation needed]

Petty crimes such as pickpocketing, car burglary, and purse snatching are serious problems, especially in large cities. Most reported thefts occur at crowded tourist sites, on public buses or trains, or at the major railway stations.[citation needed]

Italian prisons[]

Italy's prison system is built on a law that was created in 1975, that aims at the reintegration of the prisoner in society. There are 206 prisons across the Italian territory.[36] In 2019 prisons in Italy held 60,512 prisoners, one of the highest numbers per prison in Europe. Italy is notorious for having an overpopulated prison system, in fact, the prison system in 2019 was 129% over capacity, meaning there would need to be 13,608 people less for the prison system to be at a legal and regular capacity.[37][38]

The total prison population in 2020 is 57,846, however, the official capacity of the prison system is 50,754, meaning that there is an occupancy level of 114%. Out of the twenty Italian regions, the two that suffer the most from this overcrowding are Apulia with a rate of 161%, followed by Lombardy with 137% occupancy levels. For example, cities like Como, Brescia, Larino, and Taranto have a rate of 200%, meaning two prisoners live where there is only place for one.[39] The toll of prisoners per population is 100 prisoners every 100.000 people.[37]

The prisoner population mostly consists of Italians originating principally from Campania, Apulia, Sicily, and Calabria, while the rest, being 33.4% of the prisoners, are foreign, composed of Moroccans, Albanians, Romanians, Tunisians, and Nigerians.[39]

Italian prisons are affected by a high number of suicides. On average every month four to five suicides occur in prison. Since 2000 over a thousand suicides have occurred, whereas, the total number of deaths in jails have been over 3,000.[38]

References[]

- ^ Santino, Umberto (1997). "Fighting the Mafia and Organized Crime: Italy and Europe". Centro Siciliano di Documentazione "Giuseppe Impastato". Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "Poliziotti&Co, sono davvero pochi? I numeri smontano il luogo comune: Italia al top in Europa per agenti". la Repubblica (in Italian). 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ January 23; Binh, 2019 Author: Marc Getzoff Project Coordinator: Pham. "Global Finance Magazine - World's Safest Countries 2019". Global Finance Magazine. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Global Study on Homicide. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2013.

- ^ "I numeri della criminalità in Europa: Italia maglia verde ma "spariscono" troppe auto". Il Sole 24 Ore. 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "Homicide Victims, Year 2017" (PDF). ISTAT. 2018-11-15. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ "Total number of homicides in Italy from August 2011 to July 2019". Statista. 2020-04-26. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Omicidi, mai così pochi in Italia. Crollano le vittime della mafia". Corriere della Sera. 2021-02-09. Retrieved 2021-02-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tom Kington in Rome (2009-10-01). "Mafia's influence hovers over 13m Italians, says report | World news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Mafia witness 'boasted of links to Silvio Berlusconi'". BBC News. 2009-12-04. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Italy's 'coexistence' with the mafia | Roberto Mancini | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ http://www.ansa.it/english/news/2017/07/18/naples-among-worlds-10-most-dangerous-cities-sun-5_d304e6fd-cd74-4bae-a0b7-cd7952c140e3.html

- ^ "Organized Crime in Italy generated $189 Billion in revenue in 2009".

- ^ "Crime Statistics > Rapes (most recent) by country". Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Marzio Barbagli & Asher Colombo (2010) Rapporto sulla criminalità e sicurezza in Italia 2010 Sintesi, pag. 6. Ministero dell'Interno (accessed on 14 July 2012)

- ^ "Le frodi assicurative - Bilancio sociale 2004, Unipol Assicurazioni". Bilanciounipol.it. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ "Repubblica: Statali finti malati, è truffa aggravata". Flcgil.it. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ 17 gennaio 2010. "A Napoli la truffa dei "falsi pazzi": 400 malati di mente in un quartiere". Il Sole 24 ORE. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ "Freedom in the World". Freedom House. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Examining the Links Between Organised Crime and Corruption" (PDF). Center for the Study of Democracy. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Global Corruption Barometer 2013". Transparency International. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Drug markets in Italy 2019". www.emcdda.europa.eu. 2019. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ "Drug laws and drug law offences in Italy 2019 | www.emcdda.europa.eu". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Drug use in Italy 2019". EMCDDA. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ Pandolfini, C.; Impicciatore, P.; Provasi, D.; Rocchi, F.; Campi, R.; Bonati, M. (2002). "Off-label use of drugs in Italy: a prospective, observational and multicentre study". Acta Paediatrica. 91 (3): 339–347. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb01726.x. ISSN 1651-2227. PMID 12022310. S2CID 9050709.

- ^ "Italy Country Drug Report 2019". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ "Carceri, Consiglio d'Europa: "In Italia è record di detenuti per droga, il 31%"'". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 2017-03-14. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ "Gli stranieri e lo spaccio di droghe in Italia. Superato ampiamente il livello di guardia". SIPaD - Società Italiana Patologie da Dipendenza (in Italian). 2018-10-26. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ §

- ^ Fraser, Christian (7 October 2007). "Naples at the mercy of the mob". BBC.co.uk.

- ^ "Berlusconi Takes Cabinet to Naples, Plans Tax Cuts, Crime Bill". Bloomberg.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ Emergenza rifiuti in Campania, Protezione Civile

- ^ "Cricca veneta sui rifiuti di Napoli: arrestati i fratelli Gavioli" (in Italian). Il Mattino. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "Gestione rifiuti a Napoli, undici arresti tra Venezia e Treviso" (in Italian) Archived 2014-01-25 at the Wayback Machine. Il Mattino di Padova. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ https://www.money.it/Le-citta-piu-pericolose-d-Italia

- ^ "Prison Observatory - Prison conditions in Italy". www.prisonobservatory.org. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "World Prison Brief data Italy". World Prison Brief. 2020-03-31. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carceri Italiane". Polizia Penitenziaria. 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carceri, rapporto Antigone: "Quelle italiane sono le più sovraffollate d'Europa". Diminuiscono i detenuti stranieri". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

External links[]

- Italy Black Markets Havocscope Black Market

- Crime in Italy