Italian cuisine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

| Italian cuisine |

|---|

|

|

Italian cuisine is a Mediterranean cuisine[1] consisting of the ingredients, recipes and cooking techniques developed across the Italian Peninsula since antiquity, and later spread around the world together with waves of Italian diaspora.[2][3][4]

Significant changes occurred with the colonization of the Americas and the introduction of potatoes, tomatoes, capsicums, maize and sugar beet - the latter introduced in quantity in the 18th century.[5][6] Italian cuisine is known for its regional diversity, especially between the north and the south of Italy.[7][8][9] It offers an abundance of taste, and is one of the most popular and copied in the world.[10] It influenced several cuisines around the world, chiefly that of the United States.[11]

Italian cuisine is generally characterized by its simplicity, with many dishes having only two to four main ingredients.[12] Italian cooks rely chiefly on the quality of the ingredients rather than on elaborate preparation.[13] Ingredients and dishes vary by region. Many dishes that were once regional have proliferated with variations throughout the country.

History[]

Italian cuisine has developed over the centuries. Although the country known as Italy did not unite until the 19th century, the cuisine can claim traceable roots as far back as the 4th century BC. Food and culture were very important at that time as we can see from the cookbook (Apicius) which dates to the first century BC.[14] Through the centuries, neighbouring regions, conquerors, high-profile chefs, political upheaval, and the discovery of the New World have influenced its development. Italian cuisine started to form after the fall of the Roman Empire when different cities began to separate and form their own traditions. Many different types of bread and pasta were made, and there was a variation in cooking techniques and preparation.

The country was then split for a long time and influenced by surrounding countries such as Spain, France and Central Europe. This and the trade or the location on the Silk Road with its routes to Asia influenced the local development of special dishes. Due to the climatic conditions and the different proximity to the sea, different basic foods and spices were available from region to region. Regional cuisine is represented by some of the major cities in Italy. For example, Milan (north of Italy) is known for risottos, Trieste (northeast of Italy) is known for multicultural food, Bologna (the central/middle of the country) is known for its tortellini, and Naples (the south) is famous for its pizzas.[15] A good example is the well-known spaghetti where it is believed that they spread across Africa to Sicily and then on to Naples.[16][17]

Antiquity[]

The first known Italian food writer was a Greek Sicilian named Archestratus from Syracuse in the 4th century BC. He wrote a poem that spoke of using "top quality and seasonal" ingredients. He said that flavours should not be masked by spices, herbs or other seasonings. He placed importance on simple preparation of fish.[18]

Simplicity was abandoned and replaced by a culture of gastronomy as the Roman Empire developed. By the time De re coquinaria was published in the 1st century AD, it contained 470 recipes calling for heavy use of spices and herbs. The Romans employed Greek bakers to produce breads and imported cheeses from Sicily as the Sicilians had a reputation as the best cheesemakers. The Romans reared goats for butchering, and grew artichokes and leeks.[18]

Middle Ages[]

With culinary traditions from Rome and Athens, a cuisine developed in Sicily that some consider the first real Italian cuisine.[citation needed] Arabs invaded Sicily in the 9th century, introducing spinach, almonds, and rice.[19] During the 12th century, a Norman king surveyed Sicily and saw people making long strings made from flour and water called atriya, which eventually became trii, a term still used for spaghetti in southern Italy.[20] Normans also introduced the casserole, salt cod (baccalà), and stockfish, all of which remain popular.[21]

Food preservation was either chemical or physical, as refrigeration did not exist. Meats and fish were smoked, dried, or kept on ice. Brine and salt were used to pickle items such as herring, and to cure pork. Root vegetables were preserved in brine after they had been parboiled. Other means of preservation included oil, vinegar, or immersing meat in congealed, rendered fat. For preserving fruits, liquor, honey, and sugar were used.[22]

The northern Italian regions show a mix of Germanic and Roman culture while the south reflects Arab[19] influence, as much Mediterranean cuisine was spread by Arab trade.[23] The oldest Italian book on cuisine is the 13th century Liber de coquina written in Naples. Dishes include "Roman-style" cabbage (ad usum romanorum), ad usum campanie which were "small leaves" prepared in the "Campanian manner", a bean dish from the Marca di Trevisio, a torta, compositum londardicum which are similar to dishes prepared today. Two other books from the 14th century include recipes for Roman pastello, Lasagna pie, and call for the use of salt from Sardinia or Chioggia.[24]

In the 15th century, Maestro Martino was chef to the Patriarch of Aquileia at the Vatican. His Libro de arte coquinaria describes a more refined and elegant cuisine. His book contains a recipe for Maccaroni Siciliani, made by wrapping dough around a thin iron rod to dry in the sun. The macaroni was cooked in capon stock flavored with saffron, displaying Persian influences. Of particular note is Martino's avoidance of excessive spices in favor of fresh herbs.[21] The Roman recipes include coppiette (air-dried salami) and cabbage dishes. His Florentine dishes include eggs with Bolognese torta, Sienese torta and Genoese recipes such as piperata (sweets), macaroni, squash, mushrooms, and spinach pie with onions.[25]

Martino's text was included in a 1475 book by Bartolomeo Platina printed in Venice entitled De honesta voluptate et valetudine ("On Honest Pleasure and Good Health"). Platina puts Martino's "Libro" in regional context, writing about perch from Lake Maggiore, sardines from Lake Garda, grayling from Adda, hens from Padua, olives from Bologna and Piceno, turbot from Ravenna, rudd from Lake Trasimeno, carrots from Viterbo, bass from the Tiber, roviglioni and shad from Lake Albano, snails from Rieti, figs from Tuscolo, grapes from Narni, oil from Cassino, oranges from Naples and eels from Campania. Grains from Lombardy and Campania are mentioned as is honey from Sicily and Taranto. Wine from the Ligurian coast, Greco from Tuscany and San Severino, and Trebbiano from Tuscany and Piceno are also mentioned in the book.[26]

Early modern era[]

The courts of Florence, Rome, Venice, and Ferrara were central to the cuisine. Cristoforo di Messisbugo, steward to Ippolito d'Este, published Banchetti Composizioni di Vivande in 1549. Messisbugo gives recipes for pies and tarts (containing 124 recipes with various fillings). The work emphasizes the use of Eastern spices and sugar.[27]

In 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi, personal chef to Pope Pius V, wrote his Opera in five volumes, giving a comprehensive view of Italian cooking of that period. It contains over 1,000 recipes, with information on banquets including displays and menus as well as illustrations of kitchen and table utensils. This book differs from most books written for the royal courts in its preference for domestic animals and courtyard birds rather than game.

Recipes include lesser cuts of meats such as tongue, head, and shoulder. The third volume has recipes for fish in Lent. These fish recipes are simple, including poaching, broiling, grilling, and frying after marination.

Particular attention is given to seasons and places where fish should be caught. The final volume includes pies, tarts, fritters, and a recipe for a sweet Neapolitan pizza (not the current savoury version, as tomatoes had not yet been introduced to Italy). However, such items from the New World as corn (maize) and turkey are included.[28]

In the first decade of the 17th century, Giacomo Castelvetro wrote Breve Racconto di Tutte le Radici di Tutte l'Herbe et di Tutti i Frutti (A Brief Account of All Roots, Herbs, and Fruit), translated into English by Gillian Riley. Originally from Modena, Castelvetro moved to England because he was a Protestant. The book lists Italian vegetables and fruits along with their preparation. He featured vegetables as a central part of the meal, not just as accompaniments.[28] Castelvetro favoured simmering vegetables in salted water and serving them warm or cold with olive oil, salt, fresh ground pepper, lemon juice, verjus, or orange juice. He also suggested roasting vegetables wrapped in damp paper over charcoal or embers with a drizzle of olive oil. Castelvetro's book is separated into seasons with hop shoots in the spring and truffles in the winter, detailing the use of pigs in the search for truffles.[28]

In 1662, Bartolomeo Stefani, chef to the Duchy of Mantua, published L'Arte di Ben Cucinare (English: 'The Art of Well Cooking'). He was the first to offer a section on vitto ordinario ("ordinary food"). The book described a banquet given by Duke Charles for Queen Christina of Sweden, with details of the food and table settings for each guest, including a knife, fork, spoon, glass, a plate (instead of the bowls more often used), and a napkin.[29]

Other books from this time, such as Galatheo by Giovanni della Casa, tell how scalci ("waiters") should manage themselves while serving their guests. Waiters should not scratch their heads or other parts of themselves, or spit, sniff, cough or sneeze while serving diners. The book also told diners not to use their fingers while eating and not to wipe sweat with their napkin.[29]

Modern era[]

At the beginning of the 18th century, Italian culinary books began to emphasize the regionalism of Italian cuisine rather than French cuisine. Books written then were no longer addressed to professional chefs but to bourgeois housewives.[30] Periodicals in booklet form such as La cuoca cremonese (The Cook of Cremona) in 1794 give a sequence of ingredients according to season along with chapters on meat, fish, and vegetables. As the century progressed these books increased in size, popularity, and frequency.[31]

In the 18th century, medical texts warned peasants against eating refined foods as it was believed that these were poor for their digestion and their bodies required heavy meals. It was believed by some that peasants ate poorly because they preferred eating poorly. However, many peasants had to eat rotten food and mouldy bread because that was all they could afford.[32]

In 1779, Antonio Nebbia from Macerata in the Marche region, wrote Il Cuoco Maceratese (The Cook of Macerata). Nebbia addressed the importance of local vegetables and pasta, rice, and gnocchi. For stock, he preferred vegetables and chicken over other meats.

In 1773, the Neapolitan Vincenzo Corrado's Il Cuoco Galante (The Courteous Cook) gave particular emphasis to vitto pitagorico (vegetarian food). "Pythagorean food consists of fresh herbs, roots, flowers, fruits, seeds and all that is produced in the earth for our nourishment. It is so called because Pythagoras, as is well known, only used such produce. There is no doubt that this kind of food appears to be more natural to man, and the use of meat is noxious." This book was the first to give the tomato a central role with thirteen recipes.

Zuppa alli pomidoro in Corrado's book is a dish similar to today's Tuscan pappa al pomodoro. Corrado's 1798 edition introduced a "Treatise on the Potato" after the French Antoine-Augustin Parmentier's successful promotion of the tuber.[34] In 1790, Francesco Leonardi in his book L'Apicio moderno ("Modern Apicius") sketches a history of the Italian Cuisine from the Roman Age and gives as first a recipe of a tomato-based sauce.[35]

In the 19th century, Giovanni Vialardi, chef to King Victor Emmanuel, wrote A Treatise of Modern Cookery and Patisserie with recipes "suitable for a modest household". Many of his recipes are for regional dishes from Turin including twelve for potatoes such as Genoese Cappon Magro. In 1829, Il Nuovo Cuoco Milanese Economico by Giovanni Felice Luraschi featured Milanese dishes such as kidney with anchovies and lemon and gnocchi alla Romana. Gian Battista and Giovanni Ratto's La Cucina Genovese in 1871 addressed the cuisine of Liguria. This book contained the first recipe for pesto. La Cucina Teorico-Pratica written by Ippolito Cavalcanti described the first recipe for pasta with tomatoes.[36]

La scienza in cucina e l'arte di mangiare bene (The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well), by Pellegrino Artusi, first published in 1891, is widely regarded as the canon of classic modern Italian cuisine, and it is still in print. Its recipes predominantly originate from Romagna and Tuscany, where he lived.

Ingredients[]

Italian cuisine has a great variety of different ingredients which are commonly used, ranging from fruits, vegetables, sauces, meats, etc. In the North of Italy, fish (such as cod, or baccalà), potatoes, rice, corn (maize), sausages, pork, and different types of cheeses are the most common ingredients. Pasta dishes with use of tomato are spread in all of Italy.[37][38] Italians like their ingredients fresh and subtly seasoned and spiced.[39]

In Northern Italy though there are many kinds of stuffed pasta, polenta and risotto are equally popular if not more so.[40] Ligurian ingredients include several types of fish and seafood dishes. Basil (found in pesto), nuts, and olive oil are very common. In Emilia-Romagna, common ingredients include ham (prosciutto), sausage (cotechino), different sorts of salami, truffles, grana, Parmigiano-Reggiano, and tomatoes (Bolognese sauce or ragù).

Traditional Central Italian cuisine uses ingredients such as tomatoes, all kinds of meat, fish, and pecorino cheese. In Tuscany, pasta (especially pappardelle) is traditionally served with meat sauce (including game meat). In Southern Italy, tomatoes (fresh or cooked into tomato sauce), peppers, olives and olive oil, garlic, artichokes, oranges, ricotta cheese, eggplants, zucchini, certain types of fish (anchovies, sardines and tuna), and capers are important components to the local cuisine.

Italian cuisine is also well known (and well regarded) for its use of a diverse variety of pasta. Pasta include noodles in various lengths, widths, and shapes. Most pastas may be distinguished by the shapes for which they are named—penne, maccheroni, spaghetti, linguine, fusilli, lasagne, and many more varieties that are filled with other ingredients like ravioli and tortellini.

The word pasta is also used to refer to dishes in which pasta products are a primary ingredient. It is usually served with sauce. There are hundreds of different shapes of pasta with at least locally recognized names.

Examples include spaghetti (thin rods), rigatoni (tubes or cylinders), fusilli (swirls), and lasagne (sheets). Dumplings, like gnocchi (made with potatoes or pumpkin) and noodles like spätzle, are sometimes considered pasta. They are both traditional in parts of Italy.

Pasta is categorized in two basic styles: dried and fresh. Dried pasta made without eggs can be stored for up to two years under ideal conditions, while fresh pasta will keep for a couple of days in the refrigerator. Pasta is generally cooked by boiling. Under Italian law, dry pasta (pasta secca) can only be made from durum wheat flour or durum wheat semolina, and is more commonly used in Southern Italy compared to their Northern counterparts, who traditionally prefer the fresh egg variety.

Durum flour and durum semolina have a yellow tinge in color. Italian pasta is traditionally cooked al dente (Italian: firm to the bite, meaning not too soft). Outside Italy, dry pasta is frequently made from other types of flour, but this yields a softer product. There are many types of wheat flour with varying gluten and protein levels depending on the variety of grain used.

Particular varieties of pasta may also use other grains and milling methods to make the flour, as specified by law. Some pasta varieties, such as pizzoccheri, are made from buckwheat flour. Fresh pasta may include eggs (pasta all'uovo "egg pasta"). Whole wheat pasta has become increasingly popular because of its supposed health benefits over pasta made from refined flour.

Regional variation[]

Each area has its own specialties, primarily at a regional level, but also at the provincial level. The differences can come from a bordering country (such as France or Austria), whether a region is close to the sea or the mountains, and economics.[42] Italian cuisine is also seasonal with priority placed on the use of fresh produce.[43][44]

Abruzzo and Molise[]

Pasta, meat, and vegetables are central to the cuisine of Abruzzo and Molise. Chili peppers (peperoncini) are typical of Abruzzo, where they are called diavoletti ("little devils") for their spicy heat. Due to the long history of shepherding in Abruzzo and Molise, lamb dishes are common. Lamb is often paired with pasta.[45] Mushrooms (usually wild mushrooms), rosemary, and garlic are also extensively used in Abruzzese cuisine.

Best-known is the extra virgin olive oil produced in the local farms on the hills of the region, marked by the quality level DOP and considered one of the best in the country.[46] Renowned wines like Montepulciano DOCG and Trebbiano d'Abruzzo DOC are considered amongst the world's finest wines.[47] In 2012 a bottle of Trebbiano d'Abruzzo Colline Teramane ranked #1 in the top 50 Italian wine award.[48] Centerbe ("Hundred Herbs") is a strong (72% alcohol), spicy herbal liqueur drunk by the locals. Another liqueur is genziana, a soft distillate of gentian roots.

The best-known dish from Abruzzo is arrosticini, little pieces of castrated lamb on a wooden stick and cooked on coals. The chitarra (literally "guitar") is a fine stringed tool that pasta dough is pressed through for cutting. In the province of Teramo, famous local dishes include the virtù soup (made with legumes, vegetables, and pork meat), the timballo (pasta sheets filled with meat, vegetables or rice), and the mazzarelle (lamb intestines filled with garlic, marjoram, lettuce, and various spices). The popularity of saffron, grown in the province of L'Aquila, has waned in recent years.[45] The most famous dish of Molise is cavatelli, a long shaped, handmade maccheroni-type pasta made of flour, semolina, and water, often served with meat sauce, broccoli, or mushrooms. Pizzelle cookies are a common dessert, especially around Christmas.

Apulia[]

Apulia is a massive food producer: major production includes wheat, tomatoes, zucchini, broccoli, bell peppers, potatoes, spinach, eggplants, cauliflower, fennel, endive, chickpeas, lentils, beans, and cheese (like the traditional caciocavallo cheese). Apulia is also the largest producer of olive oil in Italy. The sea offers abundant fish and seafood that are extensively used in the regional cuisine, especially oysters, and mussels.

Goat and lamb are occasionally used.[49] The region is known for pasta made from durum wheat and traditional pasta dishes featuring orecchiette-type pasta, often served with tomato sauce, potatoes, mussels, or broccoli rabe. Pasta with cherry tomatoes and arugula is also popular.[50]

Regional desserts include zeppola, doughnuts usually topped with powdered sugar and filled with custard, jelly, cannoli-style pastry cream, or a butter-and-honey mixture. For Christmas, Apulians make a very traditional rose-shaped pastry called cartellate. These are fried and dipped in vin cotto, which is either a wine or fig juice reduction.

Basilicata[]

The cuisine of Basilicata is mostly based on inexpensive ingredients and deeply anchored in rural traditions.

Pork is an integral part of the regional cuisine, often made into sausages or roasted on a spit. Famous dry sausages from the region are lucanica and soppressata. Wild boar, mutton, and lamb are also popular. Pasta sauces are generally based on meats or vegetables. The region produces cheeses like Pecorino di Filiano, Canestrato di Moliterno, Pallone di Gravina, and Paddraccio and olive oils like the Vulture.[51]

The peperone crusco, (or crusco pepper) is a staple of the local cuisine, much to be defined "The red gold of Basilicata".[52] It is consumed as a snack or as a main ingredient for several regional recipes.[53]

Among the traditional dishes are pasta con i peperoni cruschi, pasta served with dried crunchy pepper, bread crumbs and grated cheese;[54] lagane e ceci, also known as piatto del brigante (brigand's dish), pasta prepared with chick peas and peeled tomatoes;[55] tumacë me tulë, tagliatelle-dish of Arbëreshe culture; rafanata, a type of omelette with horseradish; ciaudedda, a vegetable stew with artichokes, potatoes, broad beans, and pancetta;[56] and the baccalà alla lucana, one of the few recipes made with fish. Desserts include taralli dolci, made with sugar glaze and scented with anise and calzoncelli, fried pastries filled with a cream of chestnuts and chocolate.

The most famous wine of the region is the Aglianico del Vulture, others include Matera, Terre dell'Alta Val d'Agri and Grottino di Roccanova.[57]

Basilicata is also known for its mineral waters which are sold widely in Italy. The springs are mostly located in the volcanic basin of the Vulture area.[58]

Calabria[]

In Calabria, a history of French rule under the House of Anjou and Napoleon, along with Spanish influences, affected the language and culinary skills as seen in the naming of things such as cake, gatò, from the French gateau. Seafood includes swordfish, shrimp, lobster, sea urchin, and squid. Macaroni-type pasta is widely used in regional dishes, often served with goat, beef, or pork sauce and salty ricotta.[59]

Main courses include frìttuli (prepared by boiling pork rind, meat, and trimmings in pork fat), different varieties of spicy sausages (like Nduja and Capicola), goat, and land snails. Melon and watermelon are traditionally served in a chilled fruit salad or wrapped in ham.[60] Calabrian wines include Greco di Bianco, Bivongi, Cirò, Dominici, Lamezia, Melissa, Pollino, Sant'Anna di Isola Capo Rizzuto, San Vito di Luzzi, Savuto, Scavigna, and Verbicaro.

Calabrese pizza has a Neapolitan-based structure with fresh tomato sauce and a cheese base, but is unique because of its spicy flavor. Some of the ingredients included in a Calabrese pizza are thinly sliced hot soppressata, hot capicola, hot peppers, and fresh mozzarella.

Campania[]

Campania extensively produces tomatoes, peppers, spring onions, potatoes, artichokes, fennel, lemons, and oranges which all take on the flavor of volcanic soil. The Gulf of Naples offers fish and seafood. Campania is one of the largest producers and consumers of pasta in Italy, especially spaghetti. In the regional cuisine, pasta is prepared in various styles that can feature tomato sauce, cheese, clams, and shellfish.[61]

Spaghetti alla puttanesca is a popular dish made with olives, tomatoes, anchovies, capers, chili peppers, and garlic. The region is well-known also for its mozzarella production (especially from the milk of water buffalo) that's used in a variety of dishes, including parmigiana (shallow fried eggplant slices layered with cheese and tomato sauce, then baked). Desserts include struffoli (deep fried balls of dough), ricotta-based pastiera and sfogliatelle, and rum-dipped babà.[61]

Originating in Neapolitan cuisine, pizza has become popular in many different parts of the world.[62] Pizza is an oven-baked, flat, disc-shaped bread typically topped with a tomato sauce, cheese (usually mozzarella), and various toppings depending on the culture. Since the original pizza, several other types of pizzas have evolved.

Since Naples was the capital of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, its cuisine took much from the culinary traditions of all the Campania region, reaching a balance between dishes based on rural ingredients (pasta, vegetables, cheese) and seafood dishes (fish, crustaceans, mollusks). A vast variety of recipes is influenced by the local aristocratic cuisine, like timballo and Sartù di riso, pasta or rice dishes with very elaborate preparation, while the dishes coming from the popular traditions contain inexpensive but nutritionally healthy ingredients, like pasta with beans and other pasta dishes with vegetables.

Famous regional wines are Aglianico (Taurasi), Fiano, Falanghina, and Greco di Tufo.

Emilia-Romagna[]

Emilia-Romagna is especially known for its egg and filled pasta made with soft wheat flour. The Romagna subregion is renowned for pasta dishes like , garganelli, strozzapreti, sfoglia lorda, and as well as cheeses such as , Piadina snacks are also a specialty of the subregion.

Bologna and Modena are notable for pasta dishes like tortellini, lasagne, gramigna, and tagliatelle which are found also in many other parts of the region in different declinations, while Ferrara is known for cappellacci di zucca, pumpkin-filled dumplings, and Piacenza for Pisarei e faśö, wheat gnocchi with beans and lard. The celebrated balsamic vinegar is made only in the Emilian cities of Modena and Reggio Emilia, following legally binding traditional procedures.[63]

In the Emilia subregion, except Piacenza which is heavily influenced by the cuisines of Lombardy, rice is eaten to a lesser extent than the rest of northern Italy. Polenta, a maize-based side dish, is common in both Emilia and Romagna.

Parmigiano Reggiano cheese is produced in Reggio Emilia (and it was invented in Bibbiano, a little town near Reggio Emilia; this city is also known for erbazzone, a kind of egg and vegetables quiche), Parma, Modena, and Bologna and is often used in cooking. Grana Padano cheese is produced in Piacenza.

Although the Adriatic coast is a major fishing area (well known for its eels and clams harvested in the Comacchio lagoon), the region is more famous for its meat products, especially pork-based, that include cold cuts such as Parma's prosciutto, culatello, and ; Piacenza's pancetta, coppa, and salami; Bologna's mortadella and salame rosa; , cotechino, and ; and Ferrara's . Piacenza is also known for some dishes prepared with horse and donkey meat. Regional desserts include zuppa inglese (custard-based dessert made with sponge cake and Alchermes liqueur),panpepato (Christmas cake made with pepper, chocolate, spices, and almonds), tenerina (butter and chocolate cake) and torta degli addobbi (rice and milk cake).

Friuli-Venezia Giulia[]

Friuli-Venezia Giulia conserved, in its cuisine, the historical links with Austria-Hungary. Udine and Pordenone, in the western part of Friuli, are known for their traditional San Daniele del Friuli ham, Montasio cheese, and Frico cheese dish. Other typical dishes are pitina (meatballs made of smoked meats), game, and various types of gnocchi and polenta.

The majority of the eastern regional dishes are heavily influenced by Austrian, Hungarian, Slovene and Croatian cuisines: typical dishes include Istrian stew (soup of beans, sauerkraut, potatoes, bacon, and spare ribs), Vienna sausages, goulash, ćevapi, apple strudel, gugelhupf. Pork can be spicy and is often prepared over an open hearth called a fogolar. Collio Goriziano, Friuli Isonzo, Colli Orientali del Friuli, and Ramandolo are well-known denominazione di origine controllata regional wines.

But the seafood from the Adriatic is also used in this area. While the tuna fishing has declined, the anchovies from the Gulf of Trieste off Barcola (in the local dialect: "Sardoni barcolani") are a special and sought-after delicacy.[64][65][66]

Liguria[]

Liguria is known for herbs and vegetables (as well as seafood) in its cuisine. Savory pies are popular, mixing greens and artichokes along with cheeses, milk curds, and eggs. Onions and olive oil are used. Because of a lack of land suitable for wheat, the Ligurians use chickpeas in farinata and polenta-like panissa. The former is served plain or topped with onions, artichokes, sausage, cheese or young anchovies.[67] Farinata is typically cooked in a wood-fired oven, similar to southern pizzas. Furthermore, fresh fish features heavily in Ligurian cuisine. Baccala, or salted cod, features prominently as a source of protein in coastal regions. It is traditionally prepared in a soup.

Hilly districts use chestnuts as a source of carbohydrates. Ligurian pastas include corzetti, typically stamped with traditional designs, from the Polcevera valley; pansoti , a triangular shaped ravioli filled with vegetables; piccagge, pasta ribbons made with a small amount of egg and served with artichoke sauce or pesto sauce; trenette, made from whole wheat flour cut into long strips and served with pesto; boiled beans and potatoes; and trofie, a Ligurian gnocchi made from whole grain flour and boiled potatoes, made into a spiral shape and often tossed in pesto.[67] Many Ligurians emigrated to Argentina in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influencing the cuisine of the country (which was otherwise dominated by meat and dairy products that the narrow Ligurian hinterland would have not allowed). Pesto, sauce made from basil and other herbs, is uniquely Ligurian, and features prominently among Ligurian pastas.

Lazio[]

Pasta dishes based on the use of guanciale (unsmoked bacon prepared with pig's jowl or cheeks) are often found in Lazio, such as pasta alla carbonara and pasta all'amatriciana. Another pasta dish of the region is arrabbiata, with spicy tomato sauce. The regional cuisine widely use offal, resulting in dishes like the entrail-based rigatoni with pajata sauce and coda alla vaccinara.[68]

Iconic of Lazio is cheese made from ewes' milk (Pecorino Romano), porchetta (savory, fatty, and moist boneless pork roast) and Frascati white wine. The influence of the ancient Jewish community can be noticed in the Roman cuisine's traditional carciofi alla giudia.[68]

Lombardy[]

The regional cuisine of Lombardy is heavily based upon ingredients like maize, rice, beef, pork, butter, and lard. Rice dishes are very popular in this region, often found in soups as well as risotto. The best-known version is , flavoured with saffron. Due to its characteristic yellow color, it is often called risotto giallo. The dish is sometimes served with ossobuco (cross-cut veal shanks braised with vegetables, white wine and broth).[69]

Other regional specialities include cotoletta alla milanese (a fried breaded cutlet of veal similar to Wiener schnitzel, but cooked "bone-in"), cassoeula (a typically winter dish prepared with cabbage and pork), Mostarda (rich condiment made with candied fruit and a mustard flavoured syrup), Valtellina's bresaola (air-dried salted beef), pizzoccheri (a flat ribbon pasta made with 80% buckwheat flour and 20% wheat flour cooked along with greens, cubed potatoes, and layered with pieces of Valtellina Casera cheese), casoncelli (a kind of stuffed pasta, usually garnished with melted butter and sage, typical of Brescia) and (a type of ravioli with pumpkin filling, usually garnished with melted butter and sage or tomato).[70]

Regional cheeses include Grana Padano, Gorgonzola, Crescenza, Robiola, and Taleggio (the plains of central and southern Lombardy allow intensive cattle farming). Polenta is common across the region. Regional desserts include the famous panettone (soft sweet bread with raisins and candied citron and orange chunks).

Marche[]

On the coast of Marche, fish and seafood are produced. Inland, wild and domestic pigs are used for sausages and hams. These hams are not thinly sliced, but cut into bite-sized chunks. Suckling pig, chicken, and fish are often stuffed with rosemary or fennel fronds and garlic before being roasted or placed on the spit.[71]

Ascoli, Marche's southernmost province, is well known for , (stoned olives stuffed with several minced meats, egg, and Parmesan, then fried).[72] Another well-known Marche product are the , from little town of Campofilone, a kind of hand-made pasta made only of hard grain flour and eggs, cut so thin that melts in one's mouth.

Piedmont[]

Between the Alps and the Po valley, featuring a large number of different ecosystems, the Piedmont region offers the most refined and varied cuisine of the Italian peninsula. As a point of union between traditional Italian and French cuisine, Piedmont is the Italian region with the largest number of cheeses with protected geographical status and wines under DOC. It is also the region where both the Slow Food association and the most prestigious school of Italian cooking, the University of Gastronomic Sciences, were founded.[73]

Piedmont is a region where gathering nuts, mushrooms, and cardoons, as well as hunting and fishing, are commonplace. Truffles, garlic, seasonal vegetables, cheese, and rice feature in the cuisine. Wines from the Nebbiolo grape such as Barolo and Barbaresco are produced as well as wines from the Barbera grape, fine sparkling wines, and the sweet, lightly sparkling, Moscato d'Asti. The region is also famous for its Vermouth and Ratafia production.[73]

Castelmagno is a prized cheese of the region. Piedmont is also famous for the quality of its Carrù beef (particularly bue grasso, "fat ox"), hence the tradition of eating raw meat seasoned with garlic oil, lemon, and salt; carpaccio; Brasato al vino, wine stew made from marinated beef; and boiled beef served with various sauces.[73]

The food most typical of the Piedmont tradition are the traditional agnolotti (pasta folded over with roast beef and vegetable stuffing), paniscia (a typical dish of Novara, a kind of risotto with Arborio rice or Maratelli rice, the typical kind of Saluggia beans, onion, Barbera wine, lard, salami, season vegetables, salt and pepper), taglierini (thinner version of tagliatelle), bagna cauda (sauce of garlic, anchovies, olive oil, and butter), and bicerin (hot drink made of coffee, chocolate, and whole milk). Piedmont is one of the Italian capitals of pastry and chocolate in particular, with products like Nutella, gianduiotto, and marron glacé that are famous worldwide.[73]

Sardinia[]

Suckling pig and wild boar are roasted on the spit or boiled in stews of beans and vegetables, thickened with bread. Herbs such as mint and myrtle are widely used in the regional cuisine. Sardinia also has many special types of bread, made dry, which keeps longer than high-moisture breads.[74]

Also baked are carasau bread , , a highly decorative bread, and made with flour and water only, originally meant for herders, but often served at home with tomatoes, basil, oregano, garlic, and a strong cheese. Rock lobster, scampi, squid, tuna, and sardines are the predominant seafoods.[74]

Casu marzu is a very strong cheese produced in Sardinia, but is of questionable legality due to hygiene concerns.[75]

Sicily[]

Sicily shows traces of all the cultures which established themselves on the island over the last two millennia. Although its cuisine undoubtedly has a predominantly Italian base, Sicilian food also has Spanish, Greek and Arab influences. Dionysus is said to have introduced wine to the region: a trace of historical influence from Ancient Greece.[76]

The ancient Romans introduced lavish dishes based on goose. The Byzantines favored sweet and sour flavors and the Arabs brought sugar, citrus, rice, spinach, and saffron. The Normans and Hohenstaufens had a fondness for meat dishes. The Spanish introduced items from the New World including chocolate, maize, turkey, and tomatoes.[76]

Much of the island's cuisine encourages the use of fresh vegetables such as eggplant, peppers, and tomatoes, as well as fish such as tuna, sea bream, sea bass, cuttlefish, and swordfish. In Trapani, in the extreme western corner of the island, North African influences are clear in the use of various couscous based dishes, usually combined with fish.[77] Mint is used extensively in cooking unlike the rest of Italy.

Traditional specialties from Sicily include arancini (a form of deep-fried rice croquettes), pasta alla Norma, caponata, pani ca meusa, and a host of desserts and sweets such as cannoli, granita, and cassata.[78]

Typical of Sicily is Marsala, a red, fortified wine similar to Port and largely exported.[79][80]

Trentino-Alto Adige[]

Before the Council of Trent in the middle of the 16th century, the region was known for the simplicity of its peasant cuisine. When the prelates of the Catholic Church established there, they brought the art of fine cooking with them. Later, also influences from Venice and the Austrian Habsburg Empire came in.[81]

The Trentino subregion produces various types of sausages, polenta, yogurt, cheese, potato cake, funnel cake, and freshwater fish. In the Südtirol (Alto Adige) subregion, due to the German-speaking majority population, strong Austrian and Slavic influences prevail. The most renowned local product is traditional speck juniper-flavored ham which, as Speck Alto Adige, is regulated by the European Union under the protected geographical indication (PGI) status. Goulash, knödel, apple strudel, kaiserschmarrn, krapfen, rösti, spätzle, and rye bread are regular dishes, along with potatoes, dumpling, homemade sauerkraut, and lard.[81] The territory of Bolzano is also reputed for its Müller-Thurgau white wines.

Tuscany[]

Simplicity is central to the Tuscan cuisine. Legumes, bread, cheese, vegetables, mushrooms, and fresh fruit are used. A good example of typical Tuscan food is ribollita, a notable soup whose name literally means "reboiled". Like most Tuscan cuisine, the soup has peasant origins. Ribollita was originally made by reheating (i.e. reboiling) the leftover minestrone or vegetable soup from the previous day. There are many variations but the main ingredients always include leftover bread, cannellini beans, and inexpensive vegetables such as carrot, cabbage, beans, silverbeet, cavolo nero (Tuscan kale), onion, and olive oil.

A regional Tuscan pasta known as pici resembles thick, grainy-surfaced spaghetti, and is often rolled by hand. White truffles from San Miniato appear in October and November. High-quality beef, used for the traditional Florentine steak, come from the Chianina cattle breed of the Chiana Valley and the Maremmana from Maremma.

Pork is also produced.[82] The region is well-known also for its rich game, especially wild boar, hare, fallow deer, roe deer, and pheasant that often are used to prepare pappardelle dishes. Regional desserts include panforte (prepared with honey, fruits, and nuts), ricciarelli (biscuits made using an almond base with sugar, honey, and egg white), necci (galettes made with chestnut flour) and cavallucci (cookies made with almonds, candied fruits, coriander, flour, and honey). Well-known regional wines include Brunello di Montalcino, Carmignano, Chianti, Morellino di Scansano, Parrina, Sassicaia, and Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

Umbria[]

Many Umbrian dishes are prepared by boiling or roasting with local olive oil and herbs. Vegetable dishes are popular in the spring and summer,[83] while fall and winter sees meat from hunting and black truffles from Norcia. Meat dishes include the traditional wild boar sausages, pheasants, geese, pigeons, frogs, and snails. Castelluccio is known for its lentils. Spoleto and Monteleone are known for spelt. Freshwater fish include lasca, trout, freshwater perch, grayling, eel, barbel, whitefish, and tench.[84] Orvieto and Sagrantino di Montefalco are important regional wines.

Valle d'Aosta[]

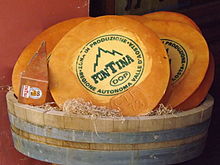

In the Aosta Valley, bread-thickened soups are customary as well as cheese fondue, chestnuts, potatoes, rice. Polenta is a staple along with rye bread, smoked bacon, Motsetta (cured chamois meat), and game from the mountains and forests. Butter and cream are important in stewed, roasted, and braised dishes.[85] Typical regional products include Fontina cheese, Vallée d'Aoste Lard d'Arnad, red wines and Génépi Artemisia-based liqueur.[86]

Veneto[]

Venice and many surrounding parts of Veneto are known for risotto, a dish whose ingredients can highly vary upon different areas. Fish and seafood are added in regions closer to the coast while pumpkin, asparagus, radicchio, and frog legs appear farther away from the Adriatic Sea.

Made from finely ground maize meal, polenta is a traditional, rural food typical of Veneto and most of Northern Italy. It may be included in stirred dishes and baked dishes. Polenta can be served with various cheese, stockfish, or meat dishes. Some polenta dishes include porcini, rapini, or other vegetables or meats, such as small song-birds in the case of the Venetian and Lombard dish polenta e osei, or sausages. In some areas of Veneto it can be also made of a particular variety of cornmeal, named biancoperla, so that the color of polenta is white and not yellow (the so-called polenta bianca).

Beans, peas, and other legumes are seen in these areas with pasta e fagioli (beans and pasta) and risi e bisi (rice and peas). Venice features heavy dishes using exotic spices and sauces. Ingredients such as stockfish or simple marinated anchovies are found here as well.

Less fish and more meat is eaten away from the coast. Other typical products are sausages such as Soppressa Vicentina, garlic salami, Piave cheese, and Asiago cheese. High quality vegetables are prized, such as red radicchio from Treviso and white asparagus from Bassano del Grappa. Perhaps the most popular dish of Venice is fegato alla veneziana, thinly-sliced veal liver sauteed with onions.

Squid and cuttlefish are common ingredients, as is squid ink, called nero di seppia.[87][88] Regional desserts include tiramisu (made of biscuits dipped in coffee, layered with a whipped mixture of egg yolks and mascarpone, and flavored with liquor and cocoa[89]), baicoli (biscuits made with butter and vanilla), and nougat.

The most celebrated Venetian wines include Bardolino, Prosecco, Soave, Amarone, and Valpolicella DOC wines.

Meal structure[]

Traditional meals in Italy typically contained four or five courses.[90] Especially on weekends, meals are often seen as a time to spend with family and friends rather than simply for sustenance; thus, meals tend to be longer than in other cultures. During holidays such as Christmas and New Year's Eve, feasts can last for hours.[91]

Today, full-course meals are mainly reserved for special events such as weddings, while everyday meals include only a first or second course (sometimes both), a side dish, and coffee. The primo (first course) is usually a filling dish such as risotto or pasta, with sauces made from meat, vegetables, or seafood. Whole pieces of meat such as sausages, meatballs, and poultry are eaten in the secondo. Italian cuisine has some single-course meals (piatto unico) combining starches and proteins. Contorni of vegetables and starches are served on a separate plate and not on the plate with the meat as is done in northern European Style serving.

| Meal stage | Composition |

|---|---|

| Aperitivo | apéritif usually enjoyed as an appetizer before a large meal, may be: Campari, Martini, Cinzano, Lucano, Prosecco, Aperol, Spritz, Vermouth, Negroni. |

| Antipasto | literally "before (the) meal", hot or cold, usually consist of cheese, ham, sliced sausage, marinated vegetables or fish, bruschetta and bread appetizers. |

| Primo | "first course", usually consists of a hot dish such as pasta, risotto, gnocchi, or soup with a sauce, vegetarian, meat or fish sugo or ragù as a sauce |

| Secondo | "second course", the main dish, usually fish or meat with potatoes. Traditionally veal, pork, and chicken are most commonly used, at least in the North, though beef has become more popular since World War II and wild game is found, particularly in Tuscany. Fish is also very popular, especially in the south. |

| Contorno | "side dish", may be a salad or cooked vegetables. A traditional menu features salad along with the main course. |

| Formaggio e frutta | "cheese and fruits", the first dessert. Local cheeses may be part of the antipasto or contorno as well. |

| Dolce | "sweet", such as cakes (like Tiramisu), cookies or ice cream |

| Caffè | coffee. |

| Digestivo | "digestives", liquors/liqueurs (grappa, amaro, limoncello, sambuca, nocino, sometimes referred to as ammazzacaffè, "coffee killer"). |

Food establishments[]

Each type of establishment has a defined role and traditionally sticks to it.[92]

| Establishment | Description |

|---|---|

| Agriturismo | Working farms that offer accommodations and meals. Sometimes meals are served to guests only. According to Italian law, they can only serve local-made products (except drinks). Marked by a green and gold sign with a knife and fork.[93] |

| Bar/Caffè | Locations which serve coffee, soft drinks, juice and alcohol. Hours are generally from 6am to 10pm. Foods may include croissants and other sweet breads (often called 'brioche' in Northern Italy), panini, tramezzini (sandwiches) and spuntini (snacks such as olives, potato crisps and small pieces of frittata).[93] |

| Birreria | A bar that offers beer; found in central and northern regions of Italy.[93] |

| Bruschetteria | Specialises in bruschetta, though other dishes may also be offered. |

| Frasca/Locanda | Friulian wine producers that open for the evening and may offer food along with their wines.[93] |

| Gelateria | An Italian ice cream shop/bar that sells gelato. A shop where the customer can get his or her gelato to go, or sit down and eat it in a cup or a cone. Bigger ice desserts, coffee, or liquors may also be ordered. |

| Osteria | Focused on simple food of the region, often having no written menu. Many are open only at night but some open for lunch.[94] The name has become fashionable for upscale restaurants with a rustic regional style. |

| Paninoteca/Panineria | Sandwich shop open during the day.[94] |

| Pizzeria | Specializing in pizza, often with wood-fired ovens.[95] |

| Polenteria | Serving polenta; uncommon, and found only in northern regions.[96] |

| Ristorante | Often offers upscale cuisine and printed menus.[95] |

| Rosticceria | Fast food restaurant, offering local dishes like cotoletta alla milanese, roasted meat (usually pork or chicken), supplì and arancini even as take-away. |

| Spaghetteria | Originating in Naples, offering pasta dishes and other main courses.[97] |

| Tavola Calda | Literally "hot table", offers pre-made regional dishes. Most open at 11am and close late.[98] |

| Trattoria | A dining establishment, often family run, with inexpensive prices and an informal atmosphere.[99] |

- Food establishments

The garden at an osteria in Castello Roganzuolo, Veneto, Italy

A pizzeria in Naples, Italy circa 1910

Interior of a trattoria in Tolmezzo, Friuli, Italy

Drinks []

Coffee[]

Italian style coffee (caffè), also known as espresso, is made from a blend of coffee beans. Espresso beans are roasted medium to medium dark in the north, and darker as one moves south.

A common misconception is that espresso has more caffeine than other coffee; in fact the opposite is true. The longer roasting period extracts more caffeine. The modern espresso machine, invented in 1937 by Achille Gaggia, uses a pump and pressure system with water heated to 90 to 95 °C (194 to 203 °F) and forced at high pressure through a few grams of finely ground coffee in 25–30 seconds, resulting in about 25 milliliters (0.85 fl oz, two tablespoons) of liquid.[100]

Home coffee makers are simpler but work under the same principle. La Napoletana is a four-part stove-top unit with grounds loosely placed inside a filter; the kettle portion is filled with water and once boiling, the unit is inverted to drip through the grounds. The Moka per il caffè is a three-part stove-top unit that is placed on the stovetop with loosely packed grounds in a strainer; the water rises from steam pressure and is forced through the grounds into the top portion. In both cases, the water passes through the grounds just once.[101]

Espresso is usually served in a demitasse cup. Caffè macchiato is topped with a bit of steamed milk or foam; ristretto is made with less water, and is stronger; cappuccino is mixed or topped with steamed, mostly frothy, milk. It is generally considered a morning beverage, and usually is not taken after a meal; caffelatte is equal parts espresso and steamed milk, similar to café au lait, and is typically served in a large cup. Latte macchiato (spotted milk) is a glass of warm milk with a bit of coffee and caffè corretto is "corrected" with a few drops of an alcoholic beverage such as grappa or brandy.

The bicerin is also an Italian coffee, from Turin. It is a mixture of cappuccino and traditional hot chocolate, as it consists of a mix of coffee and drinking chocolate, and with a small addition of milk. It is quite thick, and often whipped cream/foam with chocolate powder and sugar is added on top.

Alcoholic beverages[]

Wine[]

Italy produces the largest amount of wine in the world and is both the largest exporter and consumer of wine. Only about a quarter of this wine is put into bottles for individual sale. Two-thirds is bulk wine used for blending in France and Germany. The wine distilled into spirits in Italy exceeds the production of wine in the entirety of the New World.[102] There are twenty separate wine regions.[103]

The Italian government passed the Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) law in 1963 to regulate place of origin, quality, production method, and type of grape. The designation Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT) is a less restrictive designation to help a wine maker graduate to the DOC level. In 1980, the government created the Denominazione di origine controllata e garantita (DOCG), reserved for only the best wines.[104]

In Italy wine is commonly consumed (alongside water) in meals, which are rarely served without it, though it is extremely uncommon for meals to be served with any other drink, alcoholic, or otherwise.

Beer[]

Italy hosts a wide variety of different beers, which are usually pale lager. Beer is not as popular and widespread as wine (even though this is changing as beer becomes increasingly popular), and average beer consumption in Italy is less than in some other European nations, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and Austria. Among many popular brands, the most notable Italian breweries are Peroni and Moretti. Beer in Italy is often drunk in pizzerias, and South Tyrol (German-speaking region) is the area where beer is made and consumed the most.

Other[]

There are also several other popular alcoholic drinks in Italy. Limoncello, a traditional lemon liqueur from Campania (Sorrento, Amalfi and the Gulf of Naples) is the second most popular liqueur in Italy after Campari.[105] Made from lemon, it is an extremely strong drink which is usually consumed in very small proportions, served chilled in small glasses or cups.[105]

Amaro Sicilianos are common Sicilian digestifs, made with herbs, which are usually drunk after heavy meals. Mirto, an herbal distillate made from the berries (red mirto) and leaves (white mirto) of the myrtle bush, is popular in Sardinia and other regions. Another well-known digestif is Amaro Lucano from Basilicata.[106]

Grappa is the typical alcoholic drink of northern Italy, generally associated with the culture of the Alps and of the Po Valley. The most famous grappas are distilled in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Piedmont, and Trentino. The three most notable and recognizable Italian aperitifs are Martini, Vermouth, and Campari. A sparkling drink which is becoming internationally popular as a less expensive substitute for French champagne is prosecco, from the Veneto region.[107][108]

Desserts[]

From the Italian perspective, cookies and candy belong to the same category of sweets.[109] Traditional candies include candied fruits, torrone, and nut brittles, all of which are still popular in the modern era. In medieval times, northern Italy became so famous for the quality of its stiff fruit pastes (similar to marmalade or conserves, except stiff enough to mold into shapes) that "Paste of Genoa" became a generic name for high-quality fruit conserves.[110]

Silver-coated almond dragées, which are called confetti, are thrown at weddings. The idea of including a romantic note with candy may have begun with Italian dragées, no later than the early 19th century, and is carried on with the multilingual love notes included in boxes of Italy's most famous chocolate, Baci by Perugina in Milan.[111] The most significant chocolate style is a combination of hazelnuts and milk chocolate, which is featured in gianduja pastes like Nutella, which is made by Ferrero SpA in Alba, Piedmont, as well as Perugnia's Baci and many other chocolate confections.[109]

Panettone is a traditional Christmas cake

Gelato is Italian ice cream

Panna Cotta with garnish

Tiramisu with cocoa powder garnish

Cannoli with pistachio, candied fruit, and chocolate chips

Cassata marzipan cake

Sfogliatelle with custard filling

Neapolitan rum baba

Holiday cuisine[]

Every region has its own holiday recipes. During La Festa di San Giuseppe (St. Joseph's Day) on 19 March, Sicilians give thanks to St. Joseph for preventing a famine during the Middle Ages.[112][113] The fava bean saved the population from starvation, and is a traditional part of St. Joseph's Day altars and traditions.[114] Other customs celebrating this festival include wearing red clothing, eating Sicilian pastries known as zeppole and giving food to the poor.

On Easter Sunday, lamb is served throughout Italy. A typical Easter Sunday breakfast in Umbria and Tuscany includes salami, boiled eggs, wine, Easter Cakes, and pizza. The common cake for Easter Day is the Colomba Pasquale (literally, Easter dove), which is often simply known as "Italian Easter cake" abroad. It is supposed to represent the dove, and is topped with almonds and pearl sugar.

On Christmas Eve a symbolic fast is observed with the cena di magro ("light dinner"), a meatless meal. Typical cakes of the Christmas season are panettone and pandoro.

Abroad[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Africa[]

Due to several Italian colonies established in Africa, mainly in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Libya, and Somalia (except the northern part, which was under British rule), there is a considerable Italian influence on the cuisines of these nations.

Libya[]

Italy's legacy from the days when Libya was invaded by Italy can be seen in the popularity of pasta on its menus, particularly sharba, a highly spiced Libyan soup. Bazin, a local specialty, is a hard paste made from barley, salt and water, and one of the most popular meals in the Libyan cuisine is batata mubatana (filled potato), consisting of fried potato pieces filled with spiced minced meat and covered with egg and breadcrumbs.

South Africa[]

All major cities and towns in South Africa have substantial populations of Italians. There are "Italian clubs" in all main cities and they have had a significant influence on the cuisine of this country. Italian foods, like ham and cheeses, are imported and some also made locally, and every city has a popular Italian restaurant or two, as well as pizzerias. Pastas are popular and eaten more and more by South Africans. The production of good quality olive oil is on the rise in South Africa, especially in the drier south-western parts where there is a more Mediterranean-type of rainfall pattern. Some oils have even won top international awards.

Europe[]

France[]

In France, the cuisine of Corsica has much in common with the Italian cuisine, since the island was from the Early Middle Ages until 1768 first of a Pisan and then a Genoese possession. This is above all relevant in the first courses and the charcuterie.

Great Britain[]

Pizza and pasta dishes such as spaghetti bolognese and lasagne with bolognese ragù and Béchamel sauce are the most popular forms of Italian food in British, notably, English, cuisine.

Slovenia[]

Italian cuisine has had a strong influence on Slovenian cuisine. For centuries, north-eastern Italy and western Slovenia have formed part of the same cultural-historical and geographical space. Between 1918 and 1945, some of western Slovenia (the Slovenian Littoral and part of Inner Carniola) were part of Italy. In addition, an autochthonous Italian minority live in Slovenian Istria.

Dishes that are shared between Slovenian cuisine and the cuisine Italian Friuli Venezia Giulia include the gubana nut roll of Friuli (known as guban'ca or potica in Slovenia) and the jota stew.

Dishes that come directly from Italian cuisine include gnocchi and some types of pasta; minestrone (mineštra in Slovene); frittata (frtalja); Prosciutto (pršut); and polenta.

North and Central America[]

United States[]

Much of Italian-American cuisine is based on that found in Campania and Sicily, heavily Americanized to reflect ingredients and conditions found in the United States. Most pizza eaten around the world derives ultimately from the Neapolitan style, if somewhat thicker and usually with more toppings in terms of quantity.

Mexico[]

Throughout the country the "torta de milanesa" is a common item offered at food carts and stalls. It is a sandwich made from locally baked bread and contains a breaded, pan-fried cutlet of pork or beef. "Pescado Veracruzano" is a dish that originates from the port city of Veracruz and features a fillet of fresh fish (usually Gulf Red Snapper) covered in a distinctly Mediterranean influenced sauce containing stewed tomatoes, garlic, green olives, and capers. Also, "espagueti" (spaghetti) and other pastas are popular in a variety of soups.

South America[]

Argentina[]

Due to large Italian immigration to Argentina, Italian food and drink is heavily featured in Argentine cuisine. An example could be milanesas (The name comes from the original cotoletta alla milanese from Milan, Italy) or breaded cutlets. Pizza (locally pronounced pisa or pitsa), for example, has been wholly subsumed and in its Argentine form more closely resembles Italian calzones than it does its Italian ancestor. There are several other Italian-Argentine dishes, such as and Argentine gnocchi.

Brazil[]

Italian cuisine is popular in Brazil, due to great immigration there in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Due to the huge Italian community, São Paulo is the place where this cuisine is most appreciated. Several types of pasta and meat, including milanesa steaks, have made their way into both daily home and street kitchens and fancy restaurants. The city has also developed its particular variety of pizza, different from both Neapolitan and American varieties, and it is largely popular on weekend dinners. In Rio de Janeiro Italian cuisine is also popular, and pizza has developed as a typical botequim counter snack.

Venezuela[]

There is considerable Italian influence in Venezuelan cuisine. Pan chabata, or Venezuelan ciabatta, pan siciliano, Sicilian bread, cannoli siciliani, Sicilian cannoli, and the drink Chinotto are examples of the Italian influence in Venezuelan food and beverages.

See also[]

- Il cucchiaio d'argento, an Italian cookbook

- Il talismano della felicità by Ada Boni, an Italian cookbook

- Italian food products

- List of Italian cheeses

- List of Italian DOP cheeses

- List of Italian dishes

- List of Italian soups

- List of Italian restaurants

- Sammarinese cuisine

- Italian meal structure

- Italian wine

Notes[]

- ^ David 1988, Introduction, pp.101–103[full citation needed]

- ^ "Italian Food | Italy". www.lifeinitaly.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "The History of Italian Cuisine I". Life in Italy. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Thoms, Ulrike. "From Migrant Food to Lifestyle Cooking: The Career of Italian Cuisine in Europe Italian Cuisine". EGO(http://www.ieg-ego.eu). Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "The Making of Italian Food...From the Beginning". Epicurean.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Del Conte, 11–21.

- ^ Related Articles (2 January 2009). "Italian cuisine". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Italian Food – Italy's Regional Dishes & Cuisine". Indigoguide.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Regional Italian Cuisine". Rusticocooking.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "How pasta became the world's favourite food". bbc. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Nancy (2 March 2007). "American Food, Cuisine". Sallybernstein.com. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ The Silver Spoon ISBN 88-7212-223-6, 1997 ed.

- ^ Mario Batali Simple Italian Food: Recipes from My Two Villages (1998), ISBN 0-609-60300-0

- ^ "History of Italian Food". yourguidetoitaly.com.

- ^ First pizzeria was settled in Naples

- ^ Kummer, Corby (1 July 1986). "Pasta". The Atlantic.

- ^ Alberto Capatti, Massimo Montanari "La cucina italiana. Storia di una cultura." (2002).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Del Conte, 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jenkins, Nancy Harmon (18 October 1989). "Arab-Sicilian Food: Tale of 1,001 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Team, Delicious Italy. "Arab Culinary Influence in Sicilian Food". Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Del Conte, 12.

- ^ Capatti, 253–254.

- ^ Capatti, 2–4.

- ^ Capatti, 6.

- ^ Capatti, 9–10.

- ^ Capatti, 10.

- ^ Del Conte, 13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Del Conte, 14, 15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Del Conte, 15.

- ^ De Conte, 16

- ^ Capatti, 158–159.

- ^ Capatti, 282–284.

- ^ Gentilcore, David (15 June 2010). Pomodoro!: A History of the Tomato in Italy. Columbia University Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-231-15206-8. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ De Conte, 17

- ^ Faccioli, 753

- ^ De Conte, 18–19

- ^ Bastianich, Lidia; Tania, Manuali. Lidia Cooks from the Heart of Italy: A Feast of 175 Regional Recipes (1st ed.).

- ^ Bastianich, Lidia; John, Mariani. How Italian Food Conquered the World (1st ed.).

- ^ Conte, Anna Del (16 May 2016). "Ten commandments of Italian cooking". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Kyle Phillips. "Northern Regional Cuisines". About.

- ^ May, Tony (1 June 2005). Italian Cuisine: The New Essential Reference to the Riches of the Italian Table. Macmillan. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-312-30280-1. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ Hazan, Marcella (27 October 1992). "Introduction". Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (Kindle and printed.) (1st ed.). Knopf. ISBN 978-0394584041. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

...Italian cooking? It would seem no single cuisine answers to that name. The cooking of Italy is really the cooking of regions that long antedate the Italian nation....

- ^ For further references: CAPATTI, A.; MONTANARI, M., Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History, Columbia University Press, 2003 – http://blog.tuscany-cooking-class.com/regional-diversity-in-italian-cuisine/[dead link]

- ^ Inc., Restaurant Agent. "Exploring Italian Cuisine: Flavorful Regions and a Fresh Perspective". tableagent.com. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 319.

- ^ "Abruzzo wine and food, Tortoreto and Abruzzo cooking – Hotel Poseidon Tortoreto". Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Italian Wine Regions". Archived from the original on 8 February 2014.

- ^ "THE BEST ITALIAN WINE IS TREBBIANO D'ABRUZZO 2007 BY VALENTINI, THEN BAROLO RESERVE MONPRIVATO CÀ D'MORISSIO 2004 BY MASCARELLO AND SASSICAIA 2009 BY SAN GUIDO ESTATE. THE "BEST ITALIAN WINE AWARDS-THE 50 BEST WINES OF ITALY" – Visualizzazione per stampa". WineNews. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Piras, 361.

- ^ Shulman, Martha (22 July 2008). "Pasta With Cherry Tomatoes and Arugula". New York Times. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "Certificazione di origine, i meccanismi di vigilanza" (PDF). consiglio.basilicata.it (in Italian and English). Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Crusco Peppers: the Red Necklaces of Basilicata Towns". lacucinaitaliana.com. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Peperoni cruschi". tasteatlas.com. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Strascinati con mollica e peperoni cruschi". tasteatlas.com. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Lagane with Chick Peas". basilicatacultural.ca. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Riley, Gillian (2007). The Oxford Companion to Italian Food. Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ^ "Basilicata". italianowine.com. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Basilicata – On the waterways: Basilicata land of Mefitis". expo2015.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Edward Lear, Diario di un viaggio a piedi – Calabria 1847, Edizione italiana a cura di Parallelo 38, Reggio Calabria, 1973

- ^ Piras, 401.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 337.

- ^ Hanna Miller Archived 12 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine "American Pie," American Heritage, April/May 2006.

- ^ Piras, 187.

- ^ Georges Desrues "Eine Lange Nacht am Meer", In: Triest - Servus Magazin (2020), p 73.

- ^ Paola Agostini, Mariarosa Brizzi: Cucina friulana - Ricettario Verlag: Giunti Demetra, Florenz 2007, ISBN 978-88-440-3360-6.

- ^ Christoph Wagner: Friaul Kochbuch. Carinthia Verlag, Klagenfurt 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 167, 177.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 291.

- ^ "Ricetta Ossobuco e risotto, piatto unico di Milano" [Recipe for ossobuco and risotto, one-course meal dish of Milano]. Le ricette de La Cucina Italiana (in Italian). Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Piras, 87.

- ^ Piras, 273

- ^ [1] Provvedimento 15 febbraio 2006: Iscrizione della denominazione «Oliva Ascolana del Piceno» nel registro delle denominazioni di origine protette e delle indicazioni geografiche protette, GURI n. 46

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Davide paolini,Prodotti Tipici D'Italia, Garzanti.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 457, 460.

- ^ "Casu frazigu – Formaggi" (PDF) (in Italian). Regione autonoma della Sardegna – ERSAT: Ente Regionale di Sviluppo e Assistenza Tecnica. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 423.

- ^ Team, Delicious Italy. "Arab Culinary Influence in Sicilian Food". Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ greatbritishchefs. "Sicily's North African Influences – Great Italian Chefs". Great Italian Chefs. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ "The Marsala wine: an English story with a Sicilian flavour | Italian Food Excellence". Italian Food Excellence. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ "What is Marsala Wine | Wine Folly". Wine Folly. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piras, 67.

- ^ Piras, 221–239.

- ^ Reference: MAXWELL, V.; LEVITON, A.; PETTERSEN, L.; Tuscany and Umbria, Lonely Planet, 2010. For the richness of Umbrian cuisine and its history: http://blog.tuscany-cooking-class.com/etruscan-roots-beyond-tuscany-umbrian-cuisine/.[dead link]

- ^ Piras, 255, 256, 260, 261.

- ^ Piras, 123, 124, 128, 133.

- ^ Inc., Restaurant Agent. "Exploring Italian Cuisine: Flavorful Regions and a Fresh Perspective". tableagent.com. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Piras, 33.

- ^ "Venice Cuisine – by food author Howard Hillman". Hillmanwonders.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "history of tiramisu". Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "Guide to the Traditional Italian Meal Structure". Cucina Toscana. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "At the Italian Dinner Table | Italian Dinner and Food Traditions". DeLallo. Retrieved 15 May 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Evans, 198–200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Evans, 200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans, 201.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans, 203

- ^ Evans, 203.

- ^ Evans, 204.

- ^ Evans, 205

- ^ Evans, 205.

- ^ Piras, 300.

- ^ Piras, 301.

- ^ Koplan, 301.

- ^ Koplan, 311.

- ^ Koplan, 307–308.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Drinking Limoncello in Italy". Luxury Retreats Magazine. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2019.[full citation needed]

- ^ Piras, 383.

- ^ Atkin, Tim, The Observer (11 November 2007). "The fizz that's the bizz". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ Dane, Ana, TheStreet.com (3 July 2006). "Pop the Cork on Prosecco". Retrieved 29 December 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richardson, Tim H. (2002). Sweets: A History of Candy. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 364–365. ISBN 1-58234-229-6.

- ^ Richardson, Tim H. (2002). Sweets: A History of Candy. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 119. ISBN 1-58234-229-6.

- ^ Richardson, Tim H. (2002). Sweets: A History of Candy. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 210. ISBN 1-58234-229-6.

- ^ Long, C.M. (2001). Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce. University of Tennessee Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-57233-110-5.

- ^ Ball, A. (2003). Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 579. ISBN 978-0-87973-910-2.[dead link]

- ^ Canatella, R. (2011). The YAT Language of New Orleans. iUniverse. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-1-4620-3295-2. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

References[]

- Capatti, Alberto and Montanari, Massimo. Italian Cuisine: a Cultural History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-231-12232-2.

- Del Conte, Anna. The Concise Gastronomy of Italy. USA: Barnes and Noble Books, 2004. ISBN 1-86205-662-5.

- Dickie, John, Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food (New York, 2008).

- Evans, Matthew; Cossi, Gabriella; D'Onghia, Peter, World Food Italy. CA: Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, 2000. ISBN 1-86450-022-0.

- Faccioli, Emilio. L'Arte della Cucina in Italia. Milano: Einaudi, 1987 (in Italian).

- Hazan, Marcella, Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, Alfred A. Knopf (27 October 1992), hardcover, 704 pages, ISBN 978-0394584041.

- Koplan, Steven; Smith, Brian H.; Weiss, Michael A.; Exploring Wine, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996. ISBN 0-471-35295-0.

- Piras, Claudia and Medagliani, Eugenio. Culinaria Italy. Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbh, 2000. ISBN 3-8290-2901-2.

Further reading[]

- Riley, Gillian (2007). The Oxford Companion to Italian Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860617-8.

- The Italian Academy of Cuisine (Accademia Italiana della Cucina) (2009). La Cucina: The Regional Cooking of Italy. Trans. Jay Hyams. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3147-0. OCLC 303040489. The longest and most extensive Italian cookbook with over 2000 recipes, including background information regarding each recipe.

- Thoms, Ulrike: From Migrant Food to Lifestyle Cooking: The Career of Italian Cuisine in Europe, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History (PDF), 2011, retrieved: 22 June 2011.

External links[]

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuisine of Italy. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Cuisine of Italy. |

- Italian Food – World's Most Influential Food. Thrillist

- Italian cuisine