Ali

| Ali عَلِيّ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

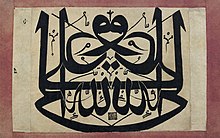

Calligraphic representation of Ali's name | |||||

| 4th Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 656–661[1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Uthman ibn Affan | ||||

| Successor | Abolished position Hasan ibn Ali (as caliph) | ||||

| 1st Shia Imam | |||||

| Tenure | 632–661 | ||||

| Predecessor | Established position | ||||

| Successor | Hasan ibn Ali | ||||

| Born | c. 600 CE Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia | ||||

| Died | c. 28 January 661 (c. 21 Ramadan AH 40) (aged c. 60) Kufa, Rashidun Caliphate (present-day Iraq) | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Tribe | Quraysh (Banu Hashim) | ||||

| Father | Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib | ||||

| Mother | Fatimah bint Asad | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

| Arabic name | |||||

| Personal (Ism) | Ali | ||||

| Patronymic (Nasab) | Ali ibn Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim ibn Abd Manaf ibn Qusai ibn Kilab | ||||

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | Abu al-Hasan[i][1] | ||||

| Epithet (Laqab) | Abu Turab[j][1] | ||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

|

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (Arabic: عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; c. 600 – 28 January 661 CE)[3][1][4] was a cousin, son-in-law and companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He ruled as the fourth Rashidun caliph from 656 until his assassination in 661. He is considered as one of the central figures in Shia Islam as the first Shia Imam and in Sunni Islam as the fourth of the "rightly guided" (rāshidūn) caliphs (name used for the first four successors to Muhammad).[1] He was the son of Abu Talib and Fatimah bint Asad, the husband of Fatima, and the father of Hasan, Husayn, Zaynab, and Umm Kulthum.[3]

As a child, Muhammad took care of him. After Muhammad's invitation of his close relatives, Ali became one of the first believers in Islam at the age of about 9 to 11.[4][5] He then publicly accepted his invitation on Yawm al-Inzar[6] and Muhammad called him his brother, guardian and successor.[4] He helped Muhammad emigrate on the night of Laylat al-Mabit, by sleeping in his place.[4] After migrating to Medina and establishing a brotherhood pact between the Muslims, Muhammad chose him as his brother.[3] In Medina, he was the flag bearer in most of the wars and became famous for his bravery.[4]

The issue of his right in the post-Muhammad caliphate caused a major rift between Muslims and divided them into Shia and Sunni groups.[1] On his return from the Farewell Pilgrimage, at Ghadir Khumm, Muhammad uttered the phrase, "Whoever I am his Mawla, this Ali is his Mawla." But the meaning of Mawla was disputed by Shias and Sunnis. On this basis, the Shias believe in the establishment of the Imamate and caliphate regarding Ali, and the Sunnis interpret the word as friendship and love.[1][7] While Ali was preparing Muhammad's body for burial, a group of Muslims met at Saqifah and pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr.[8] Ali pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr, after six months, but did not take part in the wars[9] and political activity, except for the election of the third caliph Uthman. However, he advised the three caliphs in religious, judicial, and political matters whenever they wanted.[1]

After Uthman was killed, Ali was elected as the next Caliph, which coincided with the first civil wars between Muslims. Ali faced two separate opposition forces: a group led by Aisha, Talha, and Zubayr in Mecca, who wanted to convene a council to determine the caliphate; and another group led by Mu'awiya in the Levant, who demanded revenge for Uthman's blood. He defeated the first group in the Battle of the Camel; but in the end, the Battle of Siffin with Mu'awiya was militarily ineffective, and led to an arbitration which ended politically against him. Then, in the year 38 AH (658-659), he fought with the Kharijites - who considered Ali's acceptance of arbitration as heresy, and revolted against him - in Nahrawan and defeated them.[4] Ali was eventually killed in the mosque of Kufa by the sword of one of the Kharijites, Ibn Muljam Moradi, and was buried outside the city of Kufa. Later his shrine and the city of Najaf were built around his tomb.[4]

Despite the impact of religious differences on Muslim historiography, sources agree that Ali strictly observed religious duties and avoided worldly possessions. Some writers accused him of a lack of political skill and flexibility.[3] According to Wilferd Madelung, Ali did not want to involve himself in the game of political deception which deprived him of success in life, but, in the eyes of his admirers, he became an example of the piety of the primary un-corrupted Islam, as well as the chivalry of pre-Islamic Arabia.[10] Several books are dedicated to the hadiths, sermons, and prayers narrated by him, the most famous of which is Nahj al-Balagha.

Early life

Ali was born to Abu Talib and his wife Fatima bint Asad around 600 CE,[11] possibly on 13 Rajab,[12][13] the date also celebrated annually by the Shia.[14] Shia and some Sunni sources introduce Ali as the only person born inside Ka'ba in Mecca,[13][12][11][15] some containing miraculous descriptions of the incident.[12][16] Ali's father was a leading member of the Banu Hashim clan,[12] who also raised his nephew Muhammad after his parents died. When Abu Talib fell into poverty later, Ali was taken in at the age of five and raised by Muhammad and his wife Khadija.[13]

In 610,[13] when Ali was aged between nine to eleven,[11] Muhammad announced that he had received divine revelations (wahy). Ali was among the first to believe him and profess to Islam, either the second (after Khadija) or the third (after Khadija and Abu Bakr), a point of contention among Shia and Sunni Muslims.[17] Gleave nevertheless writes that the earliest sources seem to place Ali before Abu Bakr,[11] while Watt (d. 2006) comments that Abu Bakr's status after Muhammad's death might have been reflected back into the early Islamic records.[18][19]

Muhammad's call to Islam in Mecca lasted from 610 to 622, during which Ali provided for the needs of the Meccan Islamic community, especially the poor.[13] Some three years after the first revelation and after receiving verse 26:214,[20] Muhammad gathered his relatives for a feast, invited them to Islam, and asked for their assistance.[21] The Sunni al-Tabari (d. 923) writes that Ali was the only relative who offered his support and Muhammad subsequently announced him as his brother, his trustee, and his successor.[21][11] This declaration was met with ridicule from the infamous Abu Lahab and the guests then dispersed.[21] The announcement attributed to Muhammad is not included in the Sunni collection Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal,[22] but readily found in the Shia exegeses of verse 26:214.[22] The similar account of Ibn Ishaq (d. 767) in his Sira[23] was later omitted in the recension of the book by the Sunni Ibn Hisham (d. 833), possibly because of its Shia implications.[22] The Shia interpretation of these accounts is that Muhammad had already designated Ali as his successor from an early age.[21][24]

From migration to Medina to the death of Muhammad

In 622, Muhammad was informed of an assassination plot by the Meccan elites and it was Ali who is said to have stayed in Muhammad's house overnight to fool the assassins waiting outside, while the latter escaped to Yathrib (now Medina),[13][25] thus marking 1 AH in the Islamic calendar. This incident is given by the early exegete Ibn Abbas (d. c. 687) and some others as the reason of the revelation for verse 2:207, "But there is also a kind of man who gives his life away to please God..."[26][27][28][12] Ali too escaped Mecca soon after returning the goods entrusted to Muhammad there.[17] In Medina, Muhammad paired Muslims for fraternity pacts and he is said to have selected Ali as his brother,[29] telling him, "You are my brother in this world and the Hereafter,"[13] according to the canonical Sunni collection Sahih al-Tirmidhi.[30] Ali soon married Muhammad's daughter Fatima in 1 or 2 AH (623-5 CE),[31][32] at the age of about twenty-two.[33][13] Their union holds a special spiritual significance for Muslims, write Nasr and Afsaruddin,[13] and Muhammad said he followed divine orders to marry Fatima to Ali, narrates the Sunni al-Suyuti (d. 1505), among others.[32][34][13] The Sunni Ibn Sa'd (d. 845) and some others write that Muhammad had earlier turned down the marriage proposals by Abu Bakr and Umar.[35][32][36]

Event of Mubahala

After an inconclusive debate in 10/631-2, Muhammad and the Najranite Christians decided to engage in mubuhala, where both parties would pray to invoke God's curse upon the liar. Verse 3:61 of the Quran is associated with this incident.[37][38][39] Madelung argues based on this verse that Muhammad participated in this event alongside Ali, Fatima, and their two sons, Hasan and Husayn.[40] This is also the Shia view.[41] In contrast, most Sunni accounts by al-Tabari do not name the participants of the event, while some other Sunni historians agree with the Shia view.[40][42][39] During the event, Muhammad gathered Ali, Fatima, Hasan and Husayn under his cloak and addressed them as his ahl al-bayt, according to some Shia and Sunni sources,[43][44] including the canonical Sunni Sahih Muslim and Sahih al-Tirmidhi.[45] Madelung suggests that their inclusion by Muhammad in this significant ritual must have raised the religious rank of his family.[40] A similar view is voiced by Lalani.[46]

Missions

Ali acted as Muhammad's secretary and deputy in Medina.[30][17] He was also one of the scribes tasked by Muhammad with committing the Quran to writing.[1] In 628, Ali wrote down the terms of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the peace treaty between Muhammad and the Quraysh. In 630, Muhammad sent Abu Bakr to read the sura at-Tawbah for pilgrims in Mecca but then dispatched Ali to take over this responsibility, later explaining that he received a divine command to this effect,[42][47] as related by Musnad Ibn Hanbal[48] and the canonical Sunni collection Sunan al-Nasa'i.[12] At the request of Muhammad, Ali helped ensure that the Conquest of Mecca in 630 was bloodless and later removed the idols from Ka'ba.[13] In 631, Ali was sent to Yemen to spread the teachings of Islam,[1] as a consequence of which the Hamdanids peacefully converted.[25][12] Ali was also tasked with resolving the dispute with the Banu Jadhima, some of whom had been killed by Khalid ibn al-Walid (d. 642) after being promised safety by him.[12]

Military career

Ali accompanied Muhammad in all of his military expeditions except the Battle of Tabuk (630), during which he was left behind in charge of Medina.[25] The Hadith of Position is linked with this occasion, "Are you not content, Ali, to stand to me as Aaron stood to Moses, except that there will be no prophet after me?" This appears in Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim.[49] For the Shia, the hadith signifies Ali's usurped right to succeed Muhammad,[50] while it primarily supports the finality of Muhammad in the chain of prophets for the Sunni.[51] Ali commanded the expedition to Fadak (628) in the absence of Muhammad.[17][13]

Ali was renowned for his bravery.[29][17] He was the standard-bearer in the Battle of Badr (624) and the Battle of Khaybar (628).[30] He vigorously defended Muhammad in the Battle of Uhud (625) and the Battle of Hunayn (630),[29][13] while Veccia Vaglieri (d. 1989) attributes the Muslims' victory in the Battle of Khaybar to his courage,[17] where he is popularly said to have torn off the iron gate of the enemy fort.[29] At Uhud, Muhammad reported hearing a divine voice, "[There is] no sword but Zulfiqar [Ali's sword], [there is] no chivalrous youth (fata) but Ali,"[47][13] writes al-Tabari.[12] After defeating Amr ibn Abd Wudd, who had challenged Ali to single combat in the Battle of the Trench (627), Muhammad praised him, "Faith, in its entirety, has appeared before polytheism, in its entirety," writes the Shia Rayshahri.[12] According to Veccia Vaglieri, Ali and Zubayr oversaw the killing of the Banu Qurayza men for treachery in 5 AH,[17] though the historicity of this incident has been disputed by some,[52][53][54][55] while Shah-Kazemi comments on the defensive nature of the battles fought by Ali.[12]

Ghadir Khumm

As Muhammad was returning from the Farewell Pilgrimage in 632, he made an announcement about Ali that is interpreted differently by Sunnis and Shias.[1] He halted the caravan at Ghadir Khumm and addressed the pilgrims after the congregational prayer.[56] During his sermon, taking Ali by the hand, Muhammad asked his followers whether he was not closer (awlā) to the believers than they were to themselves. When the crowd shouted their agreement, Muhammad declared, "Whomever I am his mawla, this Ali is his mawla."[57][58] Musnad Ibn Hanbal, a canonical Sunni source, adds that Muhammad repeated this sentence three or four more times and that, after Muhammad's sermon, his companion Umar congratulated Ali, saying, "You have now become mawla of every faithful man and woman."[59] In this sermon and earlier in Mecca, Muhammad is said to have alerted Muslims about his impending death.[60] Shia sources describe the event in greater detail, linking the event to the revelation of verses 5:3 and 5:67 of the Quran.[61]

Mawla is a polysemous Arabic word which might mean 'Lord', 'guardian', 'trustee', or 'helper'.[62] Shia Muslims interpret Muhammad's announcement as a clear designation of Ali as his successor,[63] whereas Sunni Muslims view Muhammad's sermon as an expression of his close relationship with Ali and of his wish that Ali, as his cousin and son-in-law, inherit his family responsibilities upon his death.[1] Many Sufi Muslims interpret this episode as the transfer of Muhammad's spiritual power and authority to Ali, whom they regard as the wali (lit. 'friend, saint') par excellence.[1]

Wain and his coauthor have questioned the historicity of this event, citing Ibn Kathir who held that Ali was in Yemen at the time.[64] In contrast, Veccia Vaglieri writes that the narrations about Ghadir Khumm are so numerous and so well-attested that it does not seem possible to reject them.[61] This view is echoed by Dakake and Amir-Moezzi.[65] During his caliphate, Ali is said to have cited this event to support his superiority over his predecessors, namely, Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman.[66]

Life under Rashidun Caliphs

The next phase of Ali's life started in 632, after the death of Muhammad, and lasted until the assassination of Uthman ibn Affan, the third caliph, in 656. During those 24 years, Ali took no part in battle or conquest.[3]

Succession to Muhammad

While Ali was preparing Muhammad's body for burial,[67] a group of the Ansar (Medinan natives, lit. 'helpers') gathered at Saqifah with the deliberate exclusion of the Muhajirun (lit. 'migrants') to discuss the future of Muslims. Upon learning about this, Abu Bakr and Umar, both senior companions of Muhammad, rushed to join the gathering and were likely the only representatives of the Muhajirun at Saqifah, alongside Abu Ubaidah.[68] Those present at Saqifah appointed Abu Bakr as Muhammad's successor after a heated debate that is said to have become violent.[69]

There is some evidence that the case of Ali for the caliphate was unsuccessfully brought up at Saqifah,[70] though it has been suggested that in a broad council (shura) with Ali among the candidates, Ansar would have supported the caliphate of Ali because of his family ties with them and the same arguments that favored Abu Bakr over the Ansar (kinship, service to Islam, etc.) would have favored Ali over Abu Bakr.[71] Veccia Vaglieri, on the other hand, believes that Ali, just over thirty years old at the time, stood no chance in view of Arabs' (pre-Islamic) tradition of choosing leaders from their elders.[17]

After Saqifah, Omar reportedly dominated the streets of Medina with the help of the Aslam and Aws tribes,[72] and the caliphate of Abu Bakr was met with little resistance there.[73] Ali and his supporters, however, initially refused to acknowledge Abu Bakr's authority, claiming that Muhammad had earlier designated him as the successor.[74] There are Sunni and Shia reports that Umar led an armed mob to Ali's house to secure his pledge of allegiance, which led to a violent confrontation.[75] To force Ali into line, Abu Bakr later placed a boycott on Muhammad's clan, the Banu Hashim,[76] which gradually led Ali's supporters to accept the caliphate of Abu Bakr.[17]

For his part, Ali is said to have turned down proposals to forcefully pursue his claims to the caliphate,[77] including an offer from Abu Sufyan.[17] Some six months after Muhammad's death, Ali pledged his allegiance to Abu Bakr when his wife, Fatima, died.[78] Shia alleges that her death was a result of the injuries suffered in an earlier violent attack on Ali's house, led by Omar, to forcibly secure Ali's oath.[79] It has been suggested that Ali relinquished his claims to the caliphate for the sake of the unity of Islam, when it became clear that Muslims did not broadly support his cause.[80] Others have noted that Ali viewed himself as the most qualified person to lead after Muhammad by virtue of his merits and his kinship with Muhammad.[81] There is also evidence that Ali considered himself as the designated successor to Muhammad through a divine decree at the Event of the Ghadir Khumm.[82]

The conflicts after the death of Muhammad are considered the roots of the current division among Muslims.[83] Those who had accepted Abu Bakr's caliphate later became the Sunni, while the supporters of Ali's right to the caliphate eventually became the Shia.[84]

Caliphate of Abu Bakr

The beginning of Abu Bakr's caliphate was marked by controversy surrounding Muhammad's land endowments to his daughter, Fatima, the wife of Ali.[85] She requested Abu Bakr to return her property, the lands of Fadak and her share in Khaybar, which Abu Bakr refused, saying that Muhammad had told him, "We [the prophets] do not have heirs, whatever we leave is alms."[86] After this exchange, Fatima is said to have remained angry with Abu Bakr until her death, within a few months of Muhammad's death.[87][88] Abu Bakr was initially the sole witness to this statement, which later became known as the hadith of Muhammad's inheritance.[89][90][91] In effect, Abu Bakr's decree disinherited Muhammad's family and brought them to rely on general alms which Muhammad had forbidden for them in his lifetime.[92] In connection to this dispute, Ibn Sa'd relates that Ali countered Abu Bakr's claim by quoting parts of verse 27:16 of the Qur'an, "Solomon became David's heir," and verse 19:6, "Zechariah said [in his prayer: grant me a next-of-kin] who will inherit from me and inherit from the family of Jacob."[93] Explaining this ostensible conflict between the Qur'an and Abu Bakr's hadith presented a challenge for Sunni authors.[94]

The death of Fatima, the wife of Ali, was another controversial incident in this period. There is strong evidence that shortly after the appointment of Abu Bakr as caliph, Umar led an armed mob to Ali's house and threatened to set it on fire if Ali and the supporters of his caliphate, who had gathered there in solidarity, would not pledge their allegiance to Abu Bakr.[95][96][85][97] The scene soon grew violent and, in particular, Zubayr was disarmed and carried away.[95][98] The armed mob later retreated after Fatima, daughter of Muhammad, loudly admonished them.[96][99] It is widely believed that Ali withheld his oath of allegiance to Abu Bakr until after the death of Fatima, within six months of Muhammad's death.[100][29] In particular, Shia and some early Sunni sources allege a final and more violent raid to secure Ali's oath, also led by Umar, in which Fatima suffered injuries that shortly led to her miscarriage and death.[85][101][102] In contrast, the Sunni historian al-Baladhuri writes that the altercations never became violent and ended with Ali's compliance.[103] Fitzpatrick surmises that the story of the altercation reflects the political agendas of the period and should therefore be treated with caution.[104] Veccia Vaglieri, however, maintains that the Shia account is based on facts, even if it has been later extended by invented details.[105]

In sharp contrast with Muhammad's lifetime,[88][106] Ali retired from the public life during the caliphate of Abu Bakr (and later, Umar and Uthman) and mainly engaged himself with religious affairs, devoting his time to the study and teaching of the Quran.[13] This change in Ali's attitude has been described as a silent censure of the first three caliphs.[88] Ali is said to have advised Abu Bakr and Umar on government and religious matters,[13][29][107] though the mutual distrust and personal animosity of Ali with Abu Bakr and Umar is also well-documented.[108][109] Their differences were epitomized during the proceedings of the electoral council in 644 where Ali refused to be bound by the precedence of the first two caliphs.[106][88]

Caliphate of Umar

Ali remained withdrawn from public affairs during the caliphate of Umar,[110] though Nasr and coauthor write that he was consulted in matters of state.[13] According to Veccia Vaglieri, however, while it is probable that Umar asked for Ali's advice on legal issues in view of his excellent knowledge of the Quran and the sunna (prophetic precedence), it is not certain whether his advice was accepted on political matters. As an example, al-Baladhuri notes that Ali's view on diwani revenue was opposite to that of Umar, as the former believed the whole income should be distributed among Muslims. Al-Tabari writes that Ali held the lieutenancy of Madina during Umar's expedition to Syria and Palestine.[111]

Umar was evidently convinced that the Quraysh would not tolerate the combination of the prophethood and the caliphate in the Banu Hashim, the clan to which Muhammad and Ali both belonged.[112] Early in his caliphate, he confided to Ibn Abbas that Mohammad intended to expressly designate Ali as his successor during his final illness if not prevented by Umar.[113] Nevertheless, realizing the necessity of Ali's cooperation in his collaborative scheme of governance, Umar made some overtures to Ali and the Banu Hashim during his caliphate without giving them excessive economic and political power.[114] He returned Muhammad's estates in Medina to Ali and Muhammad's uncle, Abbas, though Fadak and Khayber remained as state property under Umar's control.[115] Umar also insisted on marrying Ali's daughter, Umm Kulthum, to which Ali reluctantly agreed after the former enlisted public support for his demand.[116]

Election of the third caliph

In 23 AH (644 CE), Umar was stabbed by Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz, a disgruntled Persian slave.[117] On his deathbed, he tasked a committee of six with choosing the next caliph among themselves.[118] These six men were all early companions of Muhammad from the Quraysh.[118] Ali and Uthman were the two main candidates in the committee, though it is generally believed that the makeup and configuration of the committee left little possibility for Ali's nomination.[119][120][121] Two committee members, Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas and Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf, were cousins and naturally inclined to support Ibn Awf's brother-in-law, Uthman. The tie-breaker vote was given to Ibn Awf, who offered the caliphate to Ali on the condition that he should rule in accordance with the Qur'an, the sunna, and the precedents established by the first two caliphs. Ali rejected the third condition whereas Uthman accepted it. It has been suggested that Ibn Awf was aware of Ali's disagreements with the past two caliphs and that he would have inevitably rejected the third condition.[122][123][124]

Caliphate of Uthman

Uthman's reign was marked with widespread accusations of nepotism and corruption,[125][120][126][127] and he was ultimately assassinated in 656 by dissatisfied rebels in a raid during the second siege of his residence in Medina.[128] Ali was critical of Uthman's rule, alongside other senior companions, such as Talha.[129][11] He clashed with Uthman in religious matters, arguing that Uthman had deviated from the sunna (practices of Muhammad),[11] especially regarding the religious punishments (hudud) which should be meted out in several cases, such as those of Ubayd Allah ibn Umar (accused of murder) and Walid ibn Uqba (accused of drinking).[17][11][130] Ali also opposed Uthman for changing the prayer ritual, and for declaring that he would take whatever he needed from the fey money. Ali also sought to protect Muhammad's companions such as Ibn Mas'ud, Ammar ibn Yasir, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, and Jundab ibn Kab al-Azdi, who all faced Uthman's wrath for opposing the caliph.[131][17][11][29] Prior to the rebellion, in 34 AH (654-655 CE), Ali admonished Uthman for his nepotism on behalf of other companions.[132][29]

Ali frequently acted as a mediator between the rebels and Uthman during the uprising.[133][29][17] Before their first siege in 35 AH (656 CE),[134] he warned the Egyptian rebels about the evil consequences of their advance, unlike other senior companions who urged the rebels to enter Medina.[135] Ali also led the negotiations with the rebels on behalf of Uthman and persuaded the rebels to return home by promising them, in the name of caliph, redress for all their grievances and agreeing to act as guarantor.[136][29] At the insistence of Ali, Uthman then delivered a public statement of repentance in the mosque,[137] which he later withdrew under the influence of Marwan, his cousin and secretary.[138] As their disagreements mounted, Ali refused to further represent Uthman.[139] Soon after, the Egyptian rebels returned to Medina when they intercepted a messenger of Uthman who was carrying official instructions for the governor of Egypt to punish the dissidents.[140] Marwan is often blamed for this letter rather than Uthman, who maintained his innocence about it.[141][128] Kufan and Basran rebels also arrived in Medina, but they did not participate in the siege, heeding Ali's advice for nonviolence.[142] The second siege soon escalated, and Uthman was murdered by the rebels in the final days of 35 AH (June 656).[128] During the second siege, Ali's son, Hasan, was injured while standing guard at Uthman's residence at the request of Ali,[143][144] and he also mitigated the severity of the siege by ensuring that Uthman was allowed water.[145][29]

According to Jafri, Ali likely regarded the resistance movement as a front for the just demands of the poor and disenfranchised,[146] though it is generally believed that he did not have any close ties with the rebel.[130] This spiritual rather than political support of Ali for the uprising has been noted by a number of modern historians.[17][11][29] Al-Tabari writes that Ali attempted to detach himself from the besiegers of Uthman's residence as soon as circumstances allowed him.[17] Madelung relates that, years later, Marwan told Zayn al-Abidin, the grandson of Ali, that, "No one [among the Islamic nobility] was more temperate toward our master [Uthman] than your master [Ali]."[147]

Caliphate

Election

When Uthman was killed in 656 CE by rebels from Egypt, Kufa and Basra, the potential candidates for caliphate were Ali and Talha. The Umayyads had fled Medina, and the Egyptians, prominent Muhajirun, and Ansar had gained control of the city. Among the Egyptians, Talha enjoyed some support. However, the Basrians and Kufis, who had heeded Ali's opposition to the use of violence, and most of the Ansar openly supported Ali's caliphate, and finally got the upper hand. In particular, Malik al-Ashtar, the leader of the Kufis, seems to have played a key role in facilitating the caliphate of Ali.[148] According to Poonawala, before the assassination of Uthman, the Basri and Kufi rebels were in favor of Talha and Zubayr, respectively. After the assassination of Uthman, however, both groups turned to Ali.[29]

The caliphate was offered to Ali and he accepted the position after a few days.[3] According to Madelung, many of Muhammad's companions expressed the wish to pledge allegiance to him after the assassination of Uthman. At first, Ali declined.[149] Aslan attributes Ali's initial refusal to the polarization of the Muslim community, with the rebels and their supporters calling for the restoration of the caliphate to its early years and the powerful Banu Umayyad clan demanding the punishment of the rebels for Uthman's death.[150] Later, Ali said that any pledge should be made publicly in the mosque. Malik al-Ashtar might had been the first to pledge allegiance to Ali.[151] It seems that Ali personally did not pressure anyone for a pledge. In particular, Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas, Abdullah ibn Umar and Usama ibn Zayd refused to acknowledge the authority of Ali.[152] Talha and Zubayr likely gave their pledges though they both later broke their oaths, claiming that they had pledged their allegiance to Ali under public pressure.[153] There is, however, less evidence for violence than in Abu Bakr's election, according to Madelung.[154]

It has been suggested that the assassination of Uthman created an atmosphere of tumult and panic.[155] This atmosphere might have compelled Ali into accepting the caliphate to prevent further chaos.[156] According to Caetani, this chain of events also indicates that the leading companions of Muhammad did not have an a priori agreement about the succession of Uthman.[155] It has also been proposed that the support of the Ansar and the disarray of the Umayyad clan contributed more to the election of Ali than the prestige of his alliance and family ties with Muhammad.[155] According to Madelung, the reign of Ali bore the marks of a counter-caliphate, because he was not elected by a council and did not enjoy the support of the majority of the powerful Quraysh tribe.[148] On the other hand, according to Shaban, nearly every underprivileged group rallied around Ali.[157] According to Vaglieri, the nomination of Ali by the rebels exposed him to the accusations of complicity, despite his efforts to distance himself from Uthman's murder.[158] Though he condemned Uthman's murder, Ali likely regarded the resistance movement as a front for the just demands of the poor and the disenfranchised.[159]

Ruling style

It has been suggested that, by virtue of his kinship with Muhammad and his profound knowledge of Islam's roots, Ali laid claim to the religious authority to interpret the Quran and Sunnah to meet the needs of a rapidly-changing caliphate.[160]

Ali opposed a centralized control over provincial revenues, favoring an equal distribution of the taxes and booty amongst Muslims, following the precedent of Muhammad.[161] This practice, according to Poonawala, might be an indication of Ali's policy to give equal value to all Muslims who served Islam, a policy which later garnered him considerable support among the traditional tribal leaders.[162] According to Shaban, Ali's policies earned him the strong support of the underprivileged groups, including the Ansar, who were subordinated after Muhammad by the Quraysh leadership, and the Qurra or Quranic reciters who sought pious Islamic leadership. The successful formation of this diverse coalition is attributed to Ali's charisma by Shaban.[163] In a notable incident, it has been reported that Ali rejected the request by his brother, Aqil, for public funds and instead offered to pay Aqil from his personal estate.[164]

According to Heck, Ali also forbade Muslim fighters from looting and instead distributed the taxes as salaries among the warriors, in equal proportions. This might have been the first subject of the dispute between Ali and the group that later constituted the Kharijites.[165] Since the majority of Ali's subjects were nomads and peasants, he was concerned with agriculture. In particular, he instructed his top general, Malik al-Ashtar, to pay more attention to land development than short-term taxation.[166]

Battle of the Camel

According to Vaglieri, although Aisha had supported opposition against Uthman, she had gone on pilgrimage to Mecca when they killed Uthman. On her way back to Medina, when she learned about this, and specially on hearing that the new Caliph was Ali, she returned to Mecca and engaged in an active propaganda against Ali. Later on Talha and Zubayr joined her and together they marched towards Iraq to gain more supporters.[158] They wanted Ali to punish the rioters who had killed Uthman.[167] The rebels maintained that Uthman had been justly killed, for not governing according to the Quran and Sunnah; hence, no vengeance was to be invoked.[3][168][169] According to Vaglieri, since these three leaders (Aisha, Talha, Zubayr) were in part responsible for the fate of Uthman, their reason for rising is not clear. However, Vaglieri believes, "social and economic motives, inspired by fear of the possible influence of the extremists on Ali", seem to offer a more convincing explanation.[158] Poonawala believes that Talha and Zubayr, who had previously been frustrated with their political aspirations, became even more frustrated when they faced Ali's opposition to handing over to them the governorship of Basra and Kufa. When the two heard that their supporters had gathered in Mecca, they asked Ali to allow them to leave Medina for Umrah. After that, the two broke their allegiance to Ali and blamed him for killing Uthman and asked him to prosecute the killers.[3]

After Talha and Zubayr failed to mobilize supporters in the Hijaz, they set out for Basra with several hundred soldiers, hoping to find the forces and resources needed to mobilize Iraqi supporters.[k][9][3] Ali pursued them with an army, but did not reach them.[3] The rebels captured Basra,[4] killed many people,[3] attacked the bayt al-mal, and forced Uthman ibn Hunaif, Ali's appointed governor, to leave Basra.[170] Ali preferred to enlist the support of Kufa instead of marching to Basra.[170] Abu Musa Ashaari, the governor of Kufa, had pledged allegiance to Ali before the Battle of camel, but when the war escalated, took a neutral stance,[171] and called on the people of Kufa to do the same.[170][172] Ali's supporters expelled him from Kufa,[171] and joined 6 to 12 thousand people to Ali's army.[170][172] They were the main part of Ali's force in the coming battles.[l][172] Troops encamped close to Basra. The talks lasted for many days. The two parties agreed on a peace agreement, however, according to Vaglieri, the rebels did not like the conclusion of the treaty. A brawl provoked, which expanded into a battle.[158] The Battle of the Camel started in 656, where Ali emerged victorious.[173] Aisha was not harmed;[170] Ali treated her with respect and sent her to Medina under his care.[9] He also spared Aisha's army and released them after taking allegiance.[m][170] He prevented his troops from seizing their property as spoils of war, also prevented women and children from being enslaved, which led the extremists of his corps to accuse him of apostasy.[n][170][174] Talha was wounded by Marwan ibn Hakam (according to many sources) and died.[170] Ali managed to persuade Zubair to leave the battle by reminding him of Muhammad's words about himself. Some people from the tribe of Banu Tamim pursued him and killed him conspiratorially.[170] Ali entered Basra and distributed the money he found in the treasury equally among his supporters. [o][3]

Battle of Siffin

Immediately after Battle of the Camel, Ali turned to the Levant, where Mu'awiya was the governor. He was appointed during the rein of Umar and was established there during the time of Uthman. Ali wrote a letter to him but he delayed responding, During which he prepared for battle with Ali.[4] Mu'awiya insisted on Levant autonomy under his rule and refused to pay homage to Ali on the pretext that his contingent had not participated in the election. Ali then moved his armies north and the two sides encamped at Siffin for more than one hundred days, most of the time being spent in negotiations which was on vain. Skirmishes between the parties led to the Battle of Siffin in 657 AD.[3][175]

A week of combat was followed by a violent battle known as laylat al-harir (the night of clamour). Mu'awiya's army was on the point of being routed when Amr ibn al-As advised Mu'awiya to have his soldiers hoist mus'haf[p] on their spearheads in order to cause disagreement and confusion in Ali's army.[3][175][176] This gesture implied that two sides should put down their swords and settle their dispute referring to Qur'an.[158][177] Ali warned his troops that Mu'awiya and Amr were not men of religion and Qur'an and that it was a deception, but many of Qurra[q] could not refuse the call to the Qur'an, some of them even threatened Ali that if he continued the war, they would hand him over to the enemy. Ali was forced to accept a ceasefire and consequently the arbitration of the Qur'an, according which each side were to "choose a representative to arbitrate the conflict in accordance with the Book of God".[181][176] The subject about which the arbiters were to decide was not specified at first, except that they should work things out (yusliha bayna 'l-umma).[182][177] According to Julius Wellhausen, the two armies agreed to settle the matter of who should be caliph by arbitration.[183] The question as to whether the arbiter who had to face Amr ibn al-As (Mu'awiya's arbiter) would represent Ali or the Kufans, caused a further split in Ali's army.[182][3] Ali's choice was ibn Abbas or Malik al-Ashtar, but Ash'ath ibn Qays and the Qurra rejected Ali's nominees and insisted on Abu Musa Ash'ari who had previously prevented the people of Kufa from helping Ali.[3] Ali was forced again to accept Abu Musa.[184][185] The arbitrators were to meet seven months later at a place halfway between Syria and Iraq.[186][183] The matters to be examined was not specified, but it was decided that the arbitrators would make decisions based on the interests of the Ummah, so as not to cause division and war among them; and that any opinion contrary to the Qur'an would be invalid.[3][187]

According to Vaglieri, whether Uthman's murder should be regarded as an act of justice or not, was among the issues to be determined. Since if the murder was unjust, then Mu'awiya would have the right to revenge, which, according to Vaglieri, "involve, for Ali, the loss of the caliphate."[186] Madelung also believe that not only was the condition of the arbitration against Ali, but the very acceptance of the arbitration was a political defeat for him. On the one hand, the arbitration weakened the belief of Ali's followers to the legitimacy of their position and caused a rift in Ali's army, and on the other hand, it assured the Levanties that Mu'awiya's deceptive claims were based on the Qur'an. This was, according to Madelung, a moral victory for Mu'awiya, since while both Ali and Mu'awiya knew that the arbitration would fail in the end, Mu'awiya, who was losing the war, got the opportunity to strengthen his position in the Levant and propagandize against Ali.[188]

Advent of Kharijites

During the formation of the arbitration agreement, the coalition of Ali's supporters began to disintegrate. The issue of resorting to Sunnah must have been the most important reason for Qurra's opposition. They agreed to the agreement because it was an invitation to Qur'an and peace; but the terms of the agreement had not yet been determined; there was no term according which Ali would no longer be considered the commander of the faithful;[r][3] however, the expansion of the arbitrators' authority from the Qur'an to sunnah, which was ambiguous, jeopardized the credibility of the Qur'an, Qurra argued.[s] Therefore, to their view, the arbitration was considered equivalent to individuals' ruling in the matter of religion.[3][189] Their slogan therefore was "The decision belongs to God alone" (La hukma illa li'llah).[190] Ali's response to this was that it was "words of truth by which falsehood is intended"[t][191][192] Kharijites asked Ali to resume the fight against Mu'awiya, and when he refused, they rejected to recognize him as the commander of faithful,[191] and turned against him.[177] Hence, the very same people who had forced Ali into the ceasefire, broke away from him, and became known as the Kharijites[u][177][193] They asserted that according to Qur'an,[v][194] the rebel (Mu'awiya), should be fought and overcome; and since there is such an explicit verdict in Qur'an, leaving the case to judgment of human was a sin. They camped at a place near Kufa, called Harura, and proclaimed their repentance.[195] Because they themselves first forced Ali to ceasefire which led to arbitration.[180] Ali made a visit to the camp and managed to reconcile with them. When He returned to Kufa, he explicitly stated that he will abide by the terms of the Siffin treaty. On hearing this, the Kharijites became angry, secretly met with each other and asked themselves whether staying in a land ruled by injustice was compatible with the duties of the servants of God. Those who considered it necessary to leave that land, secretly fled and asked their like-minded people in Basra to do the same, and gathered in Nahrawan.[195] The reason for the opposition of some of them, according to Fred Donner, may have been the fear that Ali would compromise with Mu'awiya and, after that, they would be called to account for their rebellion against Uthman.[196] Martin Hinds believes that Kharijites' protest was a religious protest in form, but in fact it had socio-economic intentions.[w][198]

Arbitration

The first meeting of the arbitrators took place during the month of Ramadan[3] or Shawwal 37 AH (February or March 658 AD) in the neutral zone, Dumat al-Jandal.[199] In this meeting it was decided that the deeds Uthman was accused of were not tyrannical; that he was killed unjustly; and that Mu'awiya had the right to revenge. This was, according to Madelung, a political compromise that was not based on a judicial inquiry;[x][200] and according to Martin Hinds "was no more than an irrelevant sequel to a successful divisive manoeuvre by Mu'awiya".[201] However, it was desirable for Amr al-As because it could prevent neutral people from joining Ali.[200] Ali refused to accept this state of affairs and found himself technically in breach of his pledge to abide by the arbitration.[202][203][204] Ali protested that it was contrary to the Qur'an and the Sunnah and hence not binding. Then he tried to organise a new army, but only Ansar, the remnants of the Qurra led by Malik Ashtar, and a few of their clansmen remained loyal.[3] This put Ali in a weak position even amongst his own supporters.[202] The arbitration resulted in the dissolution of Ali's coalition, and some have opined that this was Mu'awiya's intention.[3][205] Still Ali assembled his forces and mobilized them toward Syria to engage in war with Mu'awiya again,[206] however, on reaching to al-Anbar, he realized that he should move toward al-Nahrawan, to handle Kharejits' riot first.[194]

The second arbitration meeting probably took place in Muharram of 38 AH (June or July, 658 AD)[199] or Sha'ban of that year (January, 659 AD).[3] Since Ali no longer considered Abu Musa his representative and had not appointed a replacement, he had no part in the second arbitration, leaving the religious leaders of Medina, who had not participated in the first arbitration, to resolve the crisis of the Caliphate.[181] The two sides met in January of 659 to discuss the selection of the new caliph. Amr ibn al-As supported Mu'awiya, while Abu Musa preferred his son-in-law, Abdullah ibn Umar, but the latter refused to stand for election in default of unanimity. Abu Musa then proposed, and Amr agreed, to depose both Ali and Mu'awiya and submit the selection of the new caliph to a Shura. In the public declaration that followed, Abu Musa observed his part of the agreement, but Amr declared Ali deposed and confirmed Mu'awiya as caliph.[3][207][208] Abu Musa left the arbitration in anger at this treachery.[209][210]

Battle of Nahrawan

After the first arbitration, when Ali learned that Mu'awiya let people to pledge allegiance to him,[211] he tried to gather a new army, and enlist Kharijites too, by assertion that he is going, as Kharijites wished, to fight against Mu'awiya. Kharijites, however, insisted that Ali should first repent of the infidelity[206] which, in their view, he had committed by accepting arbitration. Ali angrily refused.[194][212] At this time, only the Ansar, the remnants of the Qurra led by Malik al-Ashtar, and a small number of men from their tribes remained loyal to Ali. He left Kufa with his new army to overthrow Mu'awiya.[3] While Ali was on his way to Levant, the Kharijites killed people with whom they disagreed. Therefore, Ali's army, especially al-Ash'ath ibn Qays, asked him to deal with the Kharijites first, because they felt insecure about their relatives and property. Thus, Ali first went to Nahrawan to interact with the opposition. Ali asked Kharigites to hand over the killers, but they asserted that they killed together; and that it was permissible to shed the blood of Ali's followers (Shias).[213][206]

Ali and some of his companions asked the Kharijites to renounce enmity and war, but they refused. Ali then handed over the flag of amnesty to Abu Ayyub al-Ansari and announced that whoever goes to that flag, and whoever leaves Nahrawan, and has not committed a murder, is safe. Thus, hundreds of Kharijites separated from their army, except for 1500 or 1800 (or 2800)[214] out of about 4000. Finally, Ali waited for the Kharijites to start the battle, and then attacked the remnants of their army with an army of about fourteen thousand men. It took place in 658 AD. Between 7 and 13 members of Ali's army were killed, while almost all Kharijites who drew their swords were killed and wounded.[215]

Although it was reasonable and necessary, according to Madelung, to fight the bloodthirsty insurgents who openly threatened to kill others, but they were previously among the companions of Ali, and like Ali, were the most sincere believers in the Qur'an; and, according to Madelung, could have been among Ali's most ardent allies in opposing deviations from the Qur'an; but Ali could not confess his disbelief at their request or consider other Muslims infidels; or to ignore the murders they committed. After the battle, Ali intended to march directly to Levant,[216] but Nahrawan killing, being condemned by many, also the escape of Ali's soldiers, forced him to return to Kufa and not to be able to march toward Mu'awiya.[3] The wounded were taken to Kufa by Ali's troops to be cared for by their relatives.[214]

The final years of Ali's caliphate

Following the Battle of Nahrawan, Ali's support weakened and he was compelled to abandon his second Syria campaign and return to Kufa.[217] In addition to the demoralizing effect of the Battle of Nahrawan, another contributing factor might have been Ali's refusal to grant financial favors to the tribal chiefs, which left them vulnerable to bribery; Muawiya wrote to many of them, offering money and promises, in return for undermining Ali's war efforts.[218] With the collapse of Ali's broad military coalition, Egypt fell in 658 to Muawiya, who killed Ali's governor and installed Amr ibn al-As.[219] Muawiya also began to dispatch military detachments to terrorize the civilian population, killing those who did not recognize Muawiya as caliph and looting their properties.[220] These units, which were ordered to evade Ali's forces, targeted the areas along the Euphrates, the vicinity of Kufa, and most successfully, Hejaz and Yemen.[221] Ali could not mount a timely response to these assaults.[222] In the case of the raid led by Busr ibn Abi Artat in 661, the Kufans eventually responded to Ali's calls for jihad and routed Muawiya's forces only after the latter had reached Yemen.[223] Ali was also faced with armed uprisings by the remnants of the Kharijites, as well as opposition in eastern provinces.[224] However, as the extent of the rampage by Muawiya's forces became known to the public, it appears that Ali finally found sufficient support for a renewed offensive against Muawiya, set to commence in late winter 661.[225] These plans were abandoned after Ali's assassination.[226]

Death and burial

Ali was assassinated at the age of 62 or 63 by a Kharijite, ibn Muljam, who wanted revenge for the Battle of Nahrawan.[9][214] Another report indicates that Ibn Muljam, along with two other Karijites, decided to assassinate Ali, Mu'awiya, and Amr ibn al-As simultaneously in order to rid Islam of the three men, who, in their view, were responsible for the civil war, but only succeeded in killing Ali.[9] The date of his death has been reported differently. According to Shaykh al-Mufid, he was wounded on the 19th of Ramadan 40 AH (26 January 661 AD) and died two days later.[227] Ali barred his sons from retaliating against the Kharijites, instead stipulating that, if he survived, Ibn Muljam would be pardoned whereas if he died, Ibn Muljam should be given only one equal hit, regardless of whether or not he died from the hit.[228] Ali's eldest son, Hasan, followed these instructions and Ibn Muljam was executed in retaliation.[229] According to some accounts, Ali had long known about his fate, either by his own premonition or through Muhammad, who had told Ali that his beard would be stained with the blood of his head. It is emphasized mainly in Shia sources that Ali, despite being aware of his fate at the hands of Ibn Muljam, did not take any action against him because, in Ali's words, "Would you kill one who has not yet killed me?"[227]

According to Shaykh al-Mufid, Ali did not want his grave to be exhumed and profaned by his enemies. He thus asked to be buried secretly. It was revealed later during the Abbasid caliphate by Ja'far al-Sadiq that the grave was some miles from Kufa, where a sanctuary arose later and the city Najaf was built around it.[230][210] Under the Safavid Empire, his grave became the focus of much devoted attention, exemplified in the pilgrimage made by Shah Ismail I to Najaf and Karbala.[231]

Succession

After Ali's death, Kufi Muslims pledged their allegiance to his eldest son, Hasan, as Ali on many occasions had stated that only People of the House of Muhammad were entitled to lead the Muslim community.[232] At this time, Mu'awiya held both the Levant and Egypt, and had earlier declared himself caliph. He marched his army into Iraq, the seat of Hasan's caliphate. War ensued during which Mu'awiya gradually subverted the generals and commanders of Hasan's army until his army rebelled against him. Hasan was forced to cede the caliphate to Mu'awiya, according to the Hasan–Muawiya treaty, and the latter founded the Umayyad dynasty.[233] During their reign, the Umayyads kept Ali's family and his supporters, the Shia, under heavy pressure. Regular public cursing of Ali in the congregational prayers remained a vital institution until Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz abolished it sixty years later.[234][235] According to Madelung, during this period, "Umayyad highhandedness, misrule and repression were gradually to turn the minority of Ali's admirers into a majority. In the memory of later generations Ali became the ideal Commander of the Faithful."[236]

Wives and children

Ali had fourteen sons and nineteen daughters from nine wives and several concubines, among them Hasan, Husayn and Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah played a historical role, and only five of them left descendants.[210] Ali had four children from Muhammad's youngest daughter, Fatima: Hasan, Husayn, Zaynab[1] and Umm Kulthum. His other well-known sons were Abbas, born to Umm al-Banin, and Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah,[237][238] from a freed slave girl named Khawla al-Hanafiyya.[4]

Ali's descendants from Fatima are known as Sharif or Sayyid. They are revered by Shias and Sunnis as the only surviving generation of Muhammad.[1] Ali had no other wives while Fatima was alive. Hasan was the eldest son of Ali and Fatima, and was the second Shia Imam. He also assumed the role of caliph for several months after Ali's death. In the year AH 50 he died after being poisoned by a member of his own household who, according to historians, had been motivated by Mu'awiya.[239] Husayn was the second son of Ali and Fatima, and the third Shia Imam. He rebelled against Mu'awiya's son, Yazid, in 680 AD and was killed in the battle of Karbala with his companions. In this battle, in addition to Husayn, six other sons of Ali were killed, four of whom were the sons of Umm al-Banin. Also, Hasan's three sons and Husayn's two children were killed in the battle.[240][241]

Ali's dynasty considered the leadership of the Muslims to be limited to the Ahl al-Bayt and carried out several uprisings against rulers at different times. The most important of these uprisings are the battle of Karbala, the uprising of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi by Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah, the uprising of Zayd ibn Ali and the uprising of Yahya ibn Zayd against the Umayyads. Later, Ali's family also revolted against the Abbasids, the most important of which were the uprising of Shahid Fakh and the uprising of Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya. While none of these uprisings were successful, the Idrisians, Fatimids, and Alawites of Tabarestan were finally able to form the first governments of the Ali family.[242]

Works

Most works attributed to Ali were first delivered in the form of sermons and speeches and later committed to writing by his companions. Similarly, there are supplications, such as Du'a Kumayl, which he taught his companions.[4]

Nahj al-Balagha

In the tenth century, al-Sharif al-Razi, a renowned Shia scholar, compiled a large number of sermons, letters, and sayings of Ali on various topics in Nahj al-Balagha, which has become one of the most popular and influential books in the Islamic world.[243] Nahj al-Balagha has considerably influenced the field of Arabic literature and rhetoric,[244] and is also considered an important intellectual, political work in Islam.[1] According to Nasr, however, this book was almost completely ignored in Western research until the twentieth century. The authenticity of Nahj al-Balagha has been doubted by some Western scholars,[1] and the attribution of the book to Ali and al-Razi has long been the subject of lively polemic debates among Shia and Sunni scholars, though recent academic research suggests that most of its content can indeed be attributed to Ali.[245] In particular, Modarressi cites Madarek-e Nahj al-Balagha by Ostadi which documents Nahj al-Balagha through tracking down its content in earlier sources.[246] Nevertheless, according to Nasr, the authenticity of the book has never been questioned by most Muslims and Nahj al-Balagha continues to be a religious, inspirational, and literary source among Shias and Sunnis.[1] According to Gleave, the Shaqshaqiya Sermon of Nahj al-Balagha, in which Ali lays his claim to the caliphate and his superiority over his predecessors, namely, Abu bakr, Umar, and Uthman, is the most controversial section of the book. Ali's letter to Malik al-Ashtar, in which he outlines his vision for legitimate and righteous rule has also received considerable attention.[4]

Ghurar al-Hikam wa Durar al-Kalim

Ghurar al-Hikam wa Durar al-Kalim (lit. 'exalted aphorisms and pearls of speech') was compiled by , who, according to Gleave, was either a Shafi'i jurist or a Twelver. This book consists of over ten thousand short sayings of Ali.[247][4] These pietistic and ethical statements are collected from different sources, including Nahj al-Balagha and Mi'a kalima (lit. 'Hundred sayings' of Ali) by al-Jahiz.[4]

Mus'haf of Ali

Mus'haf of Ali is said to be a copy of the Qur'an compiled by Ali, as one of the first scribes of the revelations. In his codex (mus'haf), Ali had likely arranged the chapters of the Qur'an by their time of revelation to Muhammad. There are reports that this codex also included interpretive material such as information about the abrogation (naskh) of verses. Shia sources write that, after Muhammad's death, Ali offered this codex for official use but was turned down.[248] Groups of Shias throughout history have believed in major differences between this Qur'an and the present Qur'an,[249] though this view has been rejected by the Shia Imams and large numbers of Shia clerics and Qur'an scholars.[250] Ali was also one of the main reciters of the Qur'an, and a recitation of him has survived, which, according to some scholars, is the same as the recitation of Hafs that has long been the standard version of the Qur'an.[251]

Kitab Ali

Ali was seen writing in the presence of Muhammad and many narrations from the second century AH point to a collection of Muhammad's sayings by Ali, known as Kitab Ali (lit. 'book of Ali'). Another narration states that the jurist of Mecca was aware of this book in the early second century and was sure that it was written by Ali. As for the content of the book, it is said to have contained everything that people needed in matters of lawfulness (halal) and unlawfulness (haram), such as a detailed penal code that accounted even for bodily bruises. Kitab Ali is also often linked to al-Jafr, which, in Shia belief, is said to contain esoteric teachings for Muhammad's household, dictated to Ali by Muhammad.[252] The Twelver Shia believe that al-Jafr is now in the possession of the last Imam, Mahdi.[253]

Other works

Du'a Kumayl is a supplication by Ali, well-known especially among the Shia, which he taught it to his companion, Kumayl ibn Ziyad.[y][4] Kitab al-Diyat on Islamic law, attributed to Ali, contains instructions for calculating financial compensation for victims (diya) and is quoted in its entirety in Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih, among others.[255] The judicial decisions and executive orders of Ali during his caliphate were also recorded and committed to writing by his companions.[256] According to Gleave, some works attributed to Ali are not extant, such as Ṣaḥīfat al-farāʾiḍ (a short work on inheritance law), Kitāb al-zakāt (on alms tax), as well as an exegesis of the Qur'an (tafsir). Other materials attributed to Ali are compiled in Kitab al-Kafi of al-Kulayni and the many works of al-Saduq.[4]

Ali is the first transmitter of several hundred hadiths, attributed to Muhammad, which have been compiled in different works under the title of Musnad Ali, often as part of larger collections of hadith, such as Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, a canonical Sunni source.[257] There are also multiple diwans that collect the poems attributed to Ali, though many of these poems are composed by others.[258]

Personality

In person, according to Veccia Vaglieri, Ali is represented (in Sunni sources) as bald, heavy built, short-legged, with broad shoulders, a hairy body, a long white beard, and affected by eye inflammation. Shia accounts about the appearance of Ali are markedly different from Veccia Vaglieri's description and are said to better match his reputation as a capable warrior.[259] Ali is featured heavily in Shia and Sufi artworks.[260] In manner, Veccia Vaglieri writes that Ali was rough, brusque, and unsociable.[9] Other sources, in contrast, describe Ali as cheerful, gentle, and generous.[261] Encyclopaedia Islamica suggests that nearly all sects of Islam hold Ali up as a paragon of the essential virtues, above all, justice. Sa'sa'a ibn Suhan, a companion of Ali, is reported to have said that

He [Ali] was amongst us as one of us, of gentle disposition, intense humility, leading with a light touch, even though we were in awe of him with the kind of awe that a bound prisoner has before one who holds a sword over his head.[260]

Accounts about Ali are sometimes tendentious, Veccia Vaglieri asserts, because the conflicts in which he was involved were perpetuated for centuries in polemical sectarian writings.[210] Veccia Vaglieri gives Lammens's work as an example of hostile judgment towards Ali, and Caetani's writings as a milder one. However, neither Lammens nor Caetani, according to Veccia Vaglieri, took into consideration Ali's widely reported asceticism and piety, and their impact on his policies. Veccia Vaglieri notes that Ali fought against those whom he perceived as erring Muslims as a matter of duty, in order to uphold Islam. In victory, Ali was said to have been magnanimous,[262] risking the protests of some of his supporters to prevent the enslavement of women and children. He showed his grief, wept for the dead, and even prayed over his enemies.[17] Other have noted that Ali barred his troops from commencing hostilities in the Battle of the Camel and the Battle of Nahrawan.[263] Prior to the Battle of Siffin, when his forces gained the upper hand, Ali is said to have refused to retaliate after Syrians cut off their access to drinking water.[264] According to Veccia Vaglieri, even the apparent ambiguity of Ali's attitude towards the Kharijites might be explained by his religiosity, as he faced the painful dilemma of maintaining his commitment to the arbitration, though persuaded by the Kharijites that it was a sin.[9]

Veccia Vaglieri suggests that Ali was narrow-minded and excessively rigorous in upholding his religious ideals and that he lacked political skill and flexibility, qualities that were abundantly present in Mu'awiya.[3] According to Madelung, however, Ali did not compromise his principles for political self-gain,[265] and refused to engage in the new game of political deception which ultimately deprived him of success in life but, in the eyes of his admirers, elevated him to a paragon of uncorrupted Islamic virtues, as well as pre-Islamic Arab chivalry.[10] Tabatabai similarly writes that the rule of Ali was based more on righteousness than political opportunism, as evidenced by his insistence on removing those governors whom he viewed as corrupt, including Mu'awiya.[266] According to Caetani, the divine aura that soon surrounded the figure of Ali originated in part from the impression he left on the people of his time. Expanding on this view, Veccia Vaglieri writes that what left that impression was Ali's social and economic reforms, rooted in his religious beliefs.[267]

Names and titles

In the Islamic tradition, various names and titles have been attributed to Ali, some of which express his personal characteristics and some of which are taken from certain episodes of his life. Some of these titles are Abu al-Hasan (lit. 'father of Hasan, his oldest son'), Abu Turab (lit. 'father of the dust'), Murtaza (lit. 'one who is chosen and contented'), Asadullah (lit. 'lion of God'), Haydar (lit. 'lion'), and especially among the Shias, Amir al-Mu'minin (lit. 'prince of the faithful') and Mawla al-Mottaqin (lit. 'master of the God-fearing'). For example, the title Abu Turab might be a reference to when Muhammad entered the mosque and saw Ali sleeping covered by dust, and Muhammad told him, "O father of dust, get up."[1] Veccia Vaglieri, however, suggests that this title was given to Ali by his enemies, and interpreted later as an honorific by invented accounts.[9] Twelvers consider the title of Amir al-Mu'minin to be unique to Ali.[268]

In Muslim culture

Ali's place in Muslim culture is said to be second only to that of Moḥammad.[29] Afsaruddin and Nasr further suggest that, except for the prophet, more has been written about Ali in Islamic languages than anyone else.[1] He retains his stature as an authority on Qur'anic exegesis and Islamic jurisprudence, and is regarded as a founding figure for Arabic rhetoric (balagha) and grammar.[47] Ali has also been credited with establishing the authentic style of Qur'anic recitation,[269] and is said to have heavily influenced the first generation of Qur'anic commentators.[270] He is central to mystical traditions within Islam, such as Sufism, and fulfills a high political and spiritual role in Shia and Sunni schools of thought.[z][1] In Muslim culture, Madelung writes, Ali is respected for his courage, honesty, unbending devotion to Islam, magnanimity, and equal treatment of all Muslims.[271] He is remembered, according to Jones, as a model of uncorrupted socio-political and religious righteousness.[272] Esposito further suggests that Ali still remains an archetype for political activism against social injustice.[273] Ali is also remembered as a gifted orator though Veccia Vaglieri does not extend this praise to the poems attributed to Ali.[210]

In Qur'an

According to Lalani, Ali regularly represented Muhammad in missions that were preceded or followed by Qur'anic injunctions. At an early age, Ali is said to have responded to Muhammad's call for help after the revelation of verse 26:214, which reads, "And warn thy clan, thy nearest of kin."[274] Instead of Abu Bakr, there are Shia and Sunni accounts that it was Ali who was eventually tasked with communicating the chapter (sura) at-Tawbah of the Qur'an to Meccans, after the intervention of Gabriel.[275] Ibn Abbas relates that it was when Ali facilitated Muhammad's safe escape to Medina by risking his life that verse 2:207 was revealed, praising him, "But there is also a kind of man who gives his life away to please God."[276] The recipient of wisdom is said to be Ali in the Shia and some Sunni exegeses of verse 2:269, "He gives wisdom to whomever He wishes, and he who is given wisdom is certainly given an abundant good."[277]

In the Verse of Purification, "... God desires only to remove defilement from you, o Ahl al-Bayt, and to purify you completely,"[278] Ahl al-Bayt (lit. 'people of the house') is said to refer to Ali, Fatima, and their sons by Shia and some Sunni authorities, such as al-Tirmidhi.[279] Similarly, Shia and some Sunni authors, such as Baydawi and Razi, report that, when asked about the Verse of Mawadda, "I ask no reward from you for this except love among kindred," Muhammad replied that "kindred" refers to Ali, Fatima, and their sons.[280] After inconclusive debates with a Christian delegation from Najran, there are multiple Shia and Sunni accounts that Muhammad challenged them to invoke God's wrath in the company of Ali and his family, instructed by verse 3:61 of the Qur'an, known as the Verse of Mubahala.[281] It has been widely reported that verses 76:5-22 of the Qur'an were revealed after Fatima, Ali, Hasan, and Husayn, gave away their only meal of the day to beggars who visited them, for three consecutive days.[282]

In hadith literature

A great many hadiths, attributed to Muhammad, praise the qualities of Ali. The following examples appear, with minor variations, both in standard Shia and Sunni collections of hadith:[283] ``There is no youth braver than Ali," ``No-one but a believer loves Ali, and no-one but a hypocrite (munafiq) hates Ali," ``I am from Ali, and Ali is from me, and he is the wali (lit. 'patron/master/guardian') of every believer after me," ``The truth revolves around him [Ali] wherever he goes," ``I am the City of Knowledge and Ali is its Gate (bab),"[aa] ``Ali is with the Qur'an and the Qur'an is with Ali. They will not separate from each other until they return to me at the [paradisal] pool," ``For whomever I am the mawla (lit. 'close fried/master/guardian'), Ali is his mawla."

In Islamic philosophy and mysticism

Ali is credited by some, such as Nasr and Shah-Kazemi, as the founder of Islamic theology, and his words are said to contain the first rational proofs among Muslims of the Unity of God.[285] Ibn Abil-Hadid writes that

As for theosophy and dealing with matters of divinity, it was not an Arab art. Nothing of the sort had been circulated among their distinguished figures or those of lower ranks. This art was the exclusive preserve of Greece, whose sages were its only expounders. The first one among Arabs to deal with it was Ali.[286]

In later Islamic philosophy, especially in the teachings of Mulla Sadra and his followers, such as Allameh Tabatabaei, Ali's sayings and sermons were increasingly regarded as central sources of metaphysical knowledge or divine philosophy. Members of Sadra's school regard Ali as the supreme metaphysician of Islam.[1] According to Corbin, Nahj al-Balagha may be regarded as one of the most important sources of doctrines used by Shia thinkers, especially after 1500. Its influence can be sensed in the logical co-ordination of terms, the deduction of correct conclusions, and the creation of certain technical terms in Arabic which entered the literary and philosophical language independent of the translation into Arabic of Greek texts.[287]

Some hidden or occult sciences such as jafr, Islamic numerology, and the science of the symbolic significance of the letters of the Arabic alphabet, are said to have been established by Ali in connection with al-Jafr and al-Jamia.[1]

In Sunni Islam

Ali is highly regarded in Sunni thought as one of Rashidun (Rightly-Guided) Caliphs and a close companion of Muhammad. The incorporation of Ali into Sunni orthodoxy, however, might have been a late development, according to Gleave, dating back to Ahmad ibn Hanbal. Later on, Sunni authors regularly reported Ali's legal, theological, and historical views in their works, and some particularly sought to depict him as a supporter of Sunni doctrine.[4]

In Sunni thought, Ali is seen sometimes as inferior to his predecessors, in line with the Sunni doctrine of precedence (sābiqa), which assigns higher religious authority to earlier caliphs. The most troubling element of this view, according to Gleave, is the apparent elevation of Ali in Muhammad's sayings such as "I am from Ali and Ali is from me" and "For whomever I am the mawla, Ali is his mawla." These hadiths have been reinterpreted accordingly. For instance, some have interpreted mawla as financial dependence because Ali was raised in Muhammad's household as a child. Some Sunni writers, on the other hand, acknowledge the preeminence of Ali in Islam but do not consider that a basis for political succession.[4]

In Shia Islam

It is difficult to overstate the significance of Ali in Shia belief and his name, next to Muhammad's, is incorporated into Shia's daily call to prayer (azan).[288] In Shia Islam, Ali is considered the first Imam and the belief in his rightful succession to Muhammad is an article of faith among Shia Muslims, who also accept the superiority of Ali over the rest of companions and his designation by Muhammad as successor.[289] In Shia belief, by the virtue of his imamate, Ali inherited both political and religious authority of Muhammad, even before his ascension to the caliphate. Unlike Muhammad, however, Ali was not the recipient of a divine revelation (wahy), though he is believed to have been guided by divine inspiration (ilham) in Shia theology.[290] To support this view, verse 21:73 of the Qur'an is cited among others, "We made them Imams, guiding by Our command, and We revealed to them the performance of good deeds, the maintenance of prayers, and the giving of zakat (alms), and they used to worship Us."[291] Shia Muslims believe in the infallibility (isma) of Ali,[4] citing the Verse of Purification, among others.[292] In Shia view, Ali also inherited the esoteric knowledge of Muhammad. Among the evidence to support this view is often the well-attested hadith, "I [Muhammad] am the city of knowledge, and Ali is his gate."[260] According to Momen, most Shia theologians agree that Ali did not inherently possess the knowledge of unseen (ilm al-ghayb), though glimpses of this knowledge was occasionally at his disposal.[293] Shia Muslims believe that Ali is endowed with the privilege of intercession on the day of judgment,[4] citing, for instance, verse 10:3 of the Qur'an, which includes the passage, "There is no one that can intercede with Him, unless He has given permission."[294]

Ali's words and deeds are considered as a model for the Shia community and a source of sharia law for Shia jurists.[295] Ali's piety and morality initiated a kind of mysticism among the Shias that shares some commonalities with Sufism.[4] Musta'lis consider Ali's position to be superior to that of an Imam. Shia extremists, known as Ghulat, believed that Ali had access to God's will. For example, the Nuṣayrīs considered Ali to be an incarnation of God. Some of them (Khaṭṭābiyya) regarded Ali to be superior to Muhammad.[ab][4]

In Sufism

Sufis believe that Ali inherited from Muhammad the saintly power, wilayah, that makes the spiritual journey to God possible.[1] Ali is the spiritual head of some Sufi movements[300] and nearly all Sufi orders trace their lineage to Muhammad through him, an exception being Naqshbandis, who reach Muhammad through Abu Bakr.[1] According to Gleave, even the Naqshbandis include Ali in their spiritual hierarchy by depicting how Muhammad taught him the rituals of Sufism, through which believers may reach certain stages on the Sufi path.[4] In Sufism, Ali is regarded as the founder of Jafr, the occult science of the symbolic significance of the Arabic alphabet letters.[1]

Historiography

Much has been written about Ali in historical texts, second only to Muhammad, according to Nasr and Afsaruddin. The primary sources for scholarship on the life of Ali are the Qur'an and hadiths, as well as other texts of early Islamic history. The extensive secondary sources include, in addition to works by Sunni and Shia Muslims, writings by Arab Christians, Hindus, and other non-Muslims from the Middle East and Asia and a few works by modern western scholars.[1] Since the character of Ali is of religious, political, jurisprudential, and spiritual importance to Muslims (both Shia and Sunni), his life has been analyzed and interpreted in various ways.[4] In particular, many of the Islamic sources are colored to some extent by a positive or negative bias towards Ali.[1]

The earlier western scholars, such as Caetani (d. 1935), were often inclined to dismiss as fabricated the narrations and reports gathered in later periods because the authors of these reports often advanced their own Sunni or Shia partisan views. For instance, Caetani considered the later attribution of historical reports to Ibn Abbas and Aisha as mostly fictitious since the former was often for and the latter was often against Ali. Caetani instead preferred accounts reported without isnad by the early compilers of history like Ibn Ishaq. Madelung, however, argues that Caetani's approach was inconsistent and rejects the indiscriminate dismissal of late reports. In Madelung's approach, tendentiousness of a report alone does not imply fabrication. Instead, Madelung and some later historians advocate for discerning the authenticity of historical reports on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.[301]

Until the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate, few books were written and most of the reports had been oral. The most notable work prior to this period is the Book of Sulaym ibn Qays, attributed to a companion of Ali who lived before the Abbasids.[302] When affordable paper was introduced to Muslim society, numerous monographs were written between 750 and 950. For instance, according to Robinson, at least twenty-one separate monographs were composed on the Battle of Siffin in this period, thirteen of which were authored by the renowned historian Abu Mikhnaf. Most of these monographs are, however, not extant anymore except for a few which have been incorporated in later works such as History of the Prophets and Kings by Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923).[303] More broadly, ninth- and tenth-century historians collected, selected, and arranged the available monographs.

See also

- Outline of Islam

- Glossary of Islam

- Index of Islam-related articles

- Alevism

- Ali in Muslim culture

- Al-Farooq (title)

- Ghurabiya

- Hashemites Royal Family of Jordan

- Idris I The First King of Morocco Founded 788

- List of expeditions of Ali during Muhammad's era

Notes

- ^ English: Commander of the Faithful

- ^ English: Father of the Dust

- ^ English: Commander of the Faithful

- ^ English: Gate to the City of Knowledge

- ^ English: One Who Is Chosen and Contented

- ^ English: Master of the God-Fearing

- ^ English: Lion

- ^ English: Lion of God

- ^ English: Father of Hasan

- ^ English: Father of the Dust

- ^ According to Vaglieri, ALi had no choice but to prevent them from occupying Iraq, because Levant obeyed Mu'awiya and there was chaos in Egypt as well; Thus, with the loss of Iraq, its dependent eastern provinces, including Iran, were virtually lost.[9]

- ^ That may explain Ali's choice of Kufa as his permanent capital.[172]

- ^ Regarding the allegiance of Marwan and some others from Aisha's troop, there are various reports.Some historians have said that Ali forgave them without taking allegiance.[170][174]

- ^ Ali also prevented the seizure of the property of the war victims. He only permitted the property that was found on the battlefield. They asked Ali; how it was lawful to shed the blood of these people, but their property is forbidden. Later the Khawarij raised this issue as one of the reasons for Ali's apostasy.[170][174]

- ^ This meant that he treated the old Muslims who had served Islam from the first days and the new Muslims who were involved in the conquests, equally.[9] He formed a broad coalition that added two new groups to his supporters. Qura, whose last hope was to regain their influence in Ali, and the leaders of the traditional tribes, who were fascinated by his equality in the distribution of spoils.[3]

- ^ Either parchments inscribed with verses of the Quran, or complete copies of it.

- ^ They were Qur'an readers who later on became known as Khawarij, although some of them like Malik al-Ashtar and Hujr became Shia leaders.[178] Brünnow (in his Inaugural dissertation on the Kharijites Strasbourg 1884) believes that such a change within the same group is impossible, and comes to the conclusion that Kharijites could not be the same as Qurra. Qurra stopped the war but kharijites protested against arbitration.[179] According to Wellhausen, on the other hand, the old tradition does not just say in general that the Khawarij originated from the circle of Qur'an readers, but also identifies certain names. Mis'ar ibn Fadaki al-Tamimi and Zayd ibn Husayn al-Tai with other readers forced Ali to get along with the Syrians and threatened him with the fate of Uthman if he did not comply with the request to recognize the Book of God as an arbitrator — but these two men subsequently became the most rabid Khawarij.[180]