Leydig cell

| Leydig cell | |

|---|---|

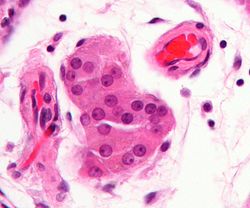

Micrograph showing a cluster of Leydig cells (center of image). H&E stain. | |

Histological section through testicular parenchyma of a boar. 1 Lumen of convoluted part of the seminiferous tubules, 2 spermatids, 3 spermatocytes, 4 spermatogonia, 5 Sertoli cell, 6 myofibroblasts, 7 Leydig cells, 8 capillaries | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D007985 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Leydig cells, also known as interstitial cells of Leydig, are found adjacent to the seminiferous tubules in the testicle. They produce testosterone in the presence of luteinizing hormone (LH). Leydig cells are polyhedral in shape, and have a large prominent nucleus, an eosinophilic cytoplasm and numerous lipid-filled vesicles.

Structure[]

The mammalian Leydig cell is a polyhedral epithelioid cell with a single eccentrically located ovoid nucleus. The nucleus contains one to three prominent nucleoli and large amounts of dark-staining peripheral heterochromatin. The acidophilic cytoplasm usually contains numerous membrane-bound lipid droplets and large amounts of smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER). Besides the obvious abundance of SER with scattered patches of rough endoplasmic reticulum, several mitochondria are also prominent within the cytoplasm. Frequently, lipofuscin pigment and rod-shaped crystal-like structures 3 to 20 micrometres in diameter (Reinke crystals) are found. These inclusions have no known function, are found in less than half of all Leydig cell tumors, but serve to clinch the diagnosis of a Leydig cell tumor.[1][2] No other interstitial cell within the testes has a nucleus or cytoplasm with these characteristics, making identification relatively easy.

Development[]

'Adult'-type Leydig cells differentiate in the post-natal testis and are quiescent until puberty. They are preceded in the testis by a population of 'fetal'-type Leydig cells from the 8th to the 20th week of gestation, which produce enough testosterone for masculinisation of a male fetus.[3]

Androgen production[]

Leydig cells release a class of hormones called androgens (19-carbon steroids).[4] They secrete testosterone, androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), when stimulated by the luteinizing hormone (LH) which is released from the anterior pituitary in response to gonadotrophin releasing hormone which in turn is released by the hypothalamus.[4] LH binds to its receptor (LHCGR) which is a G-protein coupled receptor and consequently increases the production of cAMP.[4] cAMP, in turn through protein kinase A activation, stimulates cholesterol translocation from intracellular sources (primarily the plasma membrane and intracellular stores) to the mitochondria, firstly to the outer mitochondrial membrane and then cholesterol needs to be translocated to the inner mitochondrial membrane by steroidogenic acute regulatory protein which is the rate-limiting step in steroid biosynthesis. This is followed by pregnenolone formation from the translocated cholesterol via the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme which is found in the inner mitochondrial membrane, eventually leading to testosterone synthesis and secretion by Leydig cells.[4]

Prolactin (PRL) increases the response of Leydig cells to LH by increasing the number of LH receptors expressed on Leydig cells.[citation needed]

Clinical significance[]

Leydig cells may grow uncontrollably and form a Leydig cell tumour. These tumours are usually benign in nature. They may be hormonally active, i.e. secrete testosterone (responsible for male secondary characteristics).

Adrenomyeloneuropathy is another example of a disease affecting the Leydig cell: the patient's testosterone may fall despite higher-than-normal levels of LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Lateral electrical surface stimulation therapy has been found to cause proliferation of Leydig cells in rabbits.[5]

History[]

Etymology[]

Leydig cells are named after the German anatomist Franz Leydig, who discovered them in 1850.[6]

Additional images[]

Section of a genital cord of the testis of a human embryo 3.5 cm long

Intermediate magnification micrograph of a Leydig cell tumour, H&E stain

High magnification micrograph of a Leydig cell tumour, H&E stain

Cross-section of seminiferous tubules; arrows indicate location of Leydig cells

See also[]

- Sertoli cell

- Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

References[]

- ^ Al-Agha O, Axiotis C (2007). "An in-depth look at Leydig cell tumor of the testis". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 131 (2): 311–7. doi:10.5858/2007-131-311-AILALC. PMID 17284120.

- ^ Ramnani, Dharam M (2010-06-11). "Leydig Cell Tumor : Reinke's Crystalloids". Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ Svechnikov K, Landreh L, Weisser J, Izzo G, Colón E, Svechnikova I, Söder O (2010). "Origin, development and regulation of human Leydig cells". Horm Res Paediatr. 73 (2): 93–101. doi:10.1159/000277141. PMID 20190545. S2CID 5986143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Zirkin, Barry R; Papadopoulos, Vassilios (July 2018). "Leydig cells: formation, function, and regulation". Biology of Reproduction. 99 (1): 101–111. doi:10.1093/biolre/ioy059. ISSN 0006-3363. PMC 6044347. PMID 29566165.

- ^ Bomba G, Kowalski IM, Szarek J, Zarzycki D, Pawlicki R (2001). "The effect of spinal electrostimulation on the testicular structure in rabbit". Med. Sci. Monit. 7 (3): 363–8. PMID 11386010.

- ^ synd/625 at Who Named It?

External links[]

- Histology image: 16907loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Reproductive Physiology

- Diagram at umassmed.edu

- Steroid hormone secreting cells

- Animal reproductive system

- Human cells

- Scrotum