Maundy (foot washing)

Maundy (from Old French mandé, from Latin mandatum meaning "command"),[1] or the Washing of the Feet, or Pedelavium,[2] is a religious rite observed by various Christian denominations. The Latin word mandatum is the first word sung at the ceremony of the washing of the feet, "Mandatum novum do vobis ut diligatis invicem sicut dilexi vos", from the text of John 13:34 in the Vulgate ("I give you a new commandment, That ye love one another as I have loved you", John 13:34). This is also seen as referring to the commandment of Christ that believers should emulate his loving humility in the washing of the feet (John 13:14–17). The term mandatum (mandé, maundy), therefore, was applied to the rite of foot-washing on the Thursday preceding Easter Sunday, called Maundy Thursday.

John 13:1–17 recounts Jesus' performance of this act. In verses 13:14–17, He instructs His disciples:

If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another's feet. For I have given you an example, that you should do as I have done to you. Most assuredly, I say to you, a servant is not greater than his master; nor is he who is sent greater than he who sent him. If you know these things, blessed are you if you do them.

— John 13:14–17 (NKJV)

The synoptic gospels do not record this event.

Many denominations (including Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, Mennonites, and Catholics) therefore observe the liturgical washing of the feet on Maundy Thursday of Holy Week.[1] Moreover, for some denominations, foot-washing was an example, a pattern. Many groups throughout Church history and many modern denominations have practiced foot washing as a church ordinance including Adventists, Anabaptists, Baptists, Free Will Baptists, and Pentecostals.[1]

Background[]

The root of this practice appears to be found in the hospitality customs of ancient civilizations, especially where sandals were the chief footwear. A host would provide water for guests to wash their feet, provide a servant to wash the feet of the guests or even serve the guests by washing their feet. This is mentioned in several places in the Old Testament of the Bible (e.g. Genesis 18:4; 19:2; 24:32; 43:24; I Samuel 25:41; et al.), as well as other religious and historical documents. A typical Eastern host might bow, greet, and kiss his guest, then offer water to allow the guest to wash his feet or have servants do it. Though the wearing of sandals might necessitate washing the feet, the water was also offered as a courtesy even when shoes were worn.

I Samuel 25:41 is the first biblical passage where an honored person offers to wash feet as a sign of humility. In John 12, Mary of Bethany anointed Jesus' feet presumably in gratitude for raising her brother Lazarus from the dead, and in preparation for his death and burial. The Bible records washing of the saint's feet being practised by the primitive church in I Timothy 5:10 perhaps in reference to piety, submission and/or humility. There are several names for this practice: maundy, foot washing, washing the saints' feet, pedilavium, and mandatum.

The foot washing, described in the thirteenth chapter of the Gospel of John, is concerned with the Latin title of Servus servorum dei ("Servant of the Servant of God"), which was historically reserved to the Bishops and to the Pope, also called the Bishop of Rome. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, commissioned the Twelve to be Servant of the Servant of God, and this calling to the Imitation of Christ has been firstly extended to all the bishops of the Church as the direct successors of the Apostles. The Apostles received the Holy Spirit from Jesus in the gospel of John chapter 20.22 and in fullness upon the day of the Pentecost in chapter 2 of the Book of Acts, for the evangelization and salvation of all the human race. This belief is common to Catholics, to some denominations of the Western Christianity, and is consistent and in keeping with Eastern Christian beliefs.

A main point of contention between Eastern Orthodox Christians and Western Christians is the Filioque doctrine, and the subsequent understanding concerning the progression and movement of the Holy Spirit. The Filioque doctrine is rejected by many Eastern Orthodox, whereas it is advanced by most Western Christians. Western Christians maintain that the Holy Spirit proceeds simultaneous from God the Father and God the Son, whereas many Eastern Christians maintain that God the Holy Spirit proceeds uniquely from God the Father: Eastern Christians subsequently believe that the Apostles received the Holy Spirit with his seven gifts from God the Father, and all the bishops onward, like their successors. However, this variance in belief does not impact the words of Christ and the command to his apostles to be the Servant of the Servant of God.

It is also recalled in the Latin text of the Magnificat, for which God "regarded the lowliness" of His Most Blessed Virgin Mother and, by effect of that, "magnified" her ("He hath put down the mighty from their seat: and hath exalted the humble and meek."). God also did the same to all the other creatures, both before and after the Incarnation, for:

- Jesus Christ God: as affirmed in Philippians 2:8-11;

- all the angels: the Satan's mighty pride to be like God made him the fallen angel before the starting of the creation, and also it was punished with the promised mission of a woman (Mary), a Servant of God, which would have bruise his head (Genesis 3:14-15). On the opposite side, the lowliness of St Michael the Archangel made him the head of the hierarchy of angels;

- all the human creatures: according to the promise of Jesus in Luke 14,1.7-11.

Biblical reference[]

Christian denominations that observe foot washing do so on the basis of the authoritative example and command of Jesus as found in John 13:1–15 (NKJV):

Now before the feast of the passover, when Jesus knew that his hour was come that he should depart out of this world unto the Father, having loved his own which were in the world, he loved them unto the end. And supper being ended, the devil having now put into the heart of Judas Iscariot, Simon's son, to betray him; Jesus knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands, and that he was come from God, and went to God; He riseth from supper, and laid aside his garments; and took a towel, and girded himself. After that he poureth water into a basin, and began to wash the disciples' feet, and to wipe them with the towel wherewith he was girded. Then cometh he to Simon Peter: and Peter saith unto him, Lord, dost thou wash my feet? Jesus answered and said unto him, What I do thou knowest not now; but thou shalt know hereafter. Peter saith unto him, Thou shalt never wash my feet. Jesus answered him, If I wash thee not, thou hast no part with me. Simon Peter saith unto him, Lord, not my feet only, but also my hands and my head. Jesus saith to him, He that is washed needeth not save to wash his feet, but is clean every whit: and ye are clean, but not all. For he knew who should betray him; therefore said he, Ye are not all clean. So after he had washed their feet, and had taken his garments, and was set down again, he said unto them, Know ye what I have done to you? Ye call me Master and Lord: and ye say well; for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Master, have washed your feet; ye also ought to wash one another's feet. For I have given you an example, that ye should do as I have done to you.

Jesus demonstrates the custom of the time when he comments on the lack of hospitality in one Pharisee's home by not providing water to wash his feet in Luke 7:44:

And he turned to the woman, and said unto Simon, Seest thou this woman? I entered into thine house, thou gavest me no water for my feet: but she hath washed my feet with tears, and wiped them with the hairs of her head.

History[]

The rite of foot washing finds its roots in scripture. Even after the death of the apostles or the end of the Apostolic Age, the practice was continued.

It appears to have been practiced in the early centuries of post-apostolic Christianity, though the evidence is scant. For example, Tertullian (145–220) mentions the practice in his De Corona, but gives no details as to who practiced it or how it was practiced. It was practiced by the Church at Milan (c. 380), is mentioned by the Council of Elvira (300), and is even referenced by Augustine (c. 400).

Observance of foot washing at the time of baptism was maintained in Africa, Gaul, Germany, Milan, northern Italy, and Ireland.

According to the Mennonite Encyclopedia "St. Benedict's Rule (529) for the Benedictine Order prescribed hospitality feetwashing in addition to a communal feetwashing for humility"; a statement confirmed by the Catholic Encyclopedia.[3] It apparently was established in the Roman church, though not in connection with baptism, by the 8th century.

The Albigenses observed footwashing in connection with communion, and the Waldenses' custom was to wash the feet of visiting ministers.[citation needed]

There is some evidence that it was observed by the early Hussites; and the practice was a meaningful part of the 16th century radical reformation. Foot washing was often "rediscovered" or "restored" by Protestants in revivals of religion in which the participants tried to recreate the faith and practice of the apostolic era which they had abandoned or lost.

Catholic practice[]

In Catholic Church, the ritual washing of feet is now associated with the Mass of the Lord's Supper, which celebrates in a special way the Last Supper of Jesus, before which he washed the feet of his twelve apostles.

Evidence for the practice on this day goes back at least to the latter half of the 12th century, when "the pope washed the feet of twelve sub-deacons after his Mass and of thirteen poor men after his dinner."[3] From 1570 to 1955, the Roman Missal printed, after the text of the Holy Thursday Mass, a rite of washing of feet unconnected with the Mass.[citation needed] For many years Pius IX performed the foot washing in the sala over the portico of Saint Peter's, Rome.[4]

In 1955 Pope Pius XII revised the ritual and inserted it into the Mass. Since then, the rite is celebrated after the homily that follows the reading of the gospel account of how Jesus washed the feet of his twelve apostles (John 13:1–15). Some persons who have been selected – usually twelve, but the Roman Missal does not specify the number – are led to chairs prepared in a suitable place. The priest goes to each and, with the help of the ministers, pours water over each one's feet and dries them. There are some advocates of restricting this ritual to clergy or at least men.[5]

In a notable break from the 1955 norms, Pope Francis washed the feet of two women and Muslims at a juvenile detention center in Rome 2013.[6][7] In 2016 it was announced that the Roman Missal had been revised to permit women to have their feet washed on Maundy Thursday; previously it permitted only males to do so.[8] In 2016 Catholic priests around the world washed both women's and men's feet on Holy Thursday "their gesture of humility represented to many the progress of inclusion in the Catholic church."[9]

At one time, most of the European monarchs also performed the Washing of Feet in their royal courts on Maundy Thursday, a practice continued by the Austro-Hungarian Emperor and the King of Spain up to the beginning of the 20th century (see Royal Maundy).[3] In 1181 Roger de Moulins, Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller issued a statute declaring, "In Lent every Saturday, they are accustomed to celebrate maundy for thirteen poor persons, and to wash their feet, and to give to each a shirt and new breeches and new shoes, and to three chaplains, or to three clerics out of the thirteen, three deniers and to each of the others, two deniers".[10]

Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist practice[]

Foot washing rites are practiced by many Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist churches, whereby foot washing is most often experienced in connection with Maundy Thursday services and, sometimes, at ordination services where the Bishop may wash the feet of those who are to be ordained. In certain Methodist connexions, such as the Missionary Methodist Church and the New Congregational Methodist Church, footwashing is practiced at the time that the Lord's Supper is celebrated.[11][12] Though history shows that foot washing has at times been practiced in connection with baptism, and at times as a separate occasion, by far its most common practice has been in connection with the Lord's supper service. There has been some revival of the practice as other liturgical churches have also rediscovered the practice.

Eastern Christian practice[]

Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic[]

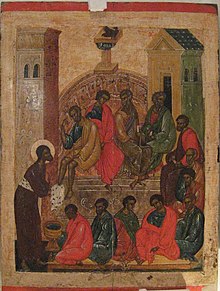

The Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches practice the ritual of the Washing of Feet on Holy and Great Thursday (Maundy Thursday) according to their ancient rites. The service may be performed either by a bishop, washing the feet of twelve priests; or by an Hegumen (Abbot) washing the feet of twelve members of the brotherhood of his monastery. The ceremony takes place at the end of the Divine Liturgy.

After Holy Communion, and before the dismissal, the brethren all go in procession to the place where the Washing of Feet is to take place (it may be in the center of the nave, in the narthex, or a location outside). After a psalm and some troparia (hymns) an ektenia (litany) is recited, and the bishop or abbot reads a prayer. Then the deacon reads the account in the Gospel of John, while the clergy perform the roles of Christ and his apostles as each action is chanted by the deacon. The deacon stops when the dialogue between Jesus and Peter begins. The senior-ranking clergyman among those whose feet are being washed speaks the words of Peter, and the bishop or abbot speaks the words of Jesus. Then the bishop or abbot himself concludes the reading of the Gospel, after which he says another prayer and sprinkles all of those present with the water that was used for the foot washing. The procession then returns to the church and the final dismissal is given as normal.

Oriental Orthodox[]

Foot washing rites are also observed in the Oriental Orthodox churches on Maundy Thursday.

In the Coptic Orthodox Church the service is performed by the parish priest. He blesses the water for the foot washing with the cross, just as he would for blessing holy water and he washes the feet of the entire congregation.

In the Syrian Orthodox Church, this service is performed by a bishop or priest. There will be some 12 selected men, both priests and the lay people, and the bishop or priest will wash and kiss the feet of those 12 men. It is not merely a dramatization of the past event. Further it is a prayer where the whole congregation prays to wash and cleanse them of their sins.

Moravian practice[]

The Moravian Church has historically practiced footwashing (pedelavium).[2] This reflected the emphasis Moravians place on practicing customs of the early Church, such as the Lovefeast.[13] In 1818, the practice was abolished.[14]

Anabaptist practice[]

Groups descending from the 1708 Schwarzenau Brethren, such as the Grace Brethren, Church of the Brethren, Brethren Church, Brethren in Christ,[15] Old German Baptist Brethren, and the Dunkard Brethren regularly practice foot washing (generally called "feetwashing"[16][17][18][19][20][21][22]) as one of three ordinances that compose their Lovefeast, the others being the Eucharist and a fellowship meal. Historically related groups such as the Amish and most Mennonites also wash feet, tracing the practice to the 1632 Dordrecht Confession of Faith. For members, this practice promotes humility towards and care for others, resulting in a higher egalitarianism among members.

Baptist practice[]

Many Baptists observe the literal washing of feet as a third ordinance. The communion and foot washing service is practiced regularly by members of the Separate Baptists in Christ, General Association of Baptists, Free Will Baptists, Primitive Baptists, Union Baptists, Old Regular Baptist, Christian Baptist Church of God.[23] Feet washing is also practiced as a third ordinance by many Southern Baptists, General Baptists, and Independent Baptists.

Pentecostal practice[]

Various Pentecostal denominations practice the ordinance or ritual of footwashing, in connection with the sacrament of the Lord's Supper or Communion, in the past.[24] Often, foot washing is held as an optional service separate from communion on a different date. When celebrated in conjunction with the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper, or communion, the Pastor, or designated minister, will read the scriptural text, out of the Gospel of St. John, then instruct the men to assemble in one location of the church, and the women to assemble in another location of the church - where basins with water and towels have already been suitably prepared in front of a pew, or row of chairs. Each member takes turns sitting in a chair or pew while another kneels before him or her and washes their feet. Customs may vary. Sometimes the foot washer places both of the other persons feet into the water, scooping water over them with his/her hand, simply holding them, sometimes the feet are held over the basin while water is poured over them, and in some congregations, only one foot is made bare and has water poured over it/washed. Often, the person whose feet are being washed lays a hand/or hands upon the shoulder of the person washing their feet and he or she will pray for the person washing their feet. The foot washer also prays for humility and for the person they are washing. When all have participated in washing the feet of others and having their feet washed, a benediction and dismissal of the service is conducted. Members are often instructed to continue their service to others in the church and to the world at large. After the dismissal, participates usually participate in helping clean up the area, basins, etc.

Restorationist practice[]

In the mid-1830s, Joseph Smith introduced the original temple rites of the Latter Day Saint movement in Kirtland, Ohio, which primarily involved foot washing, followed by speaking in tongues and visions.[25][26][27] This foot washing took place exclusively among men, and was based upon the Old and New Testament.[28] After Joseph Smith was initiated into the first three degrees of Freemasonry, this was adapted into the whole body Endowment ritual more similar to contemporary Mormon practice, which is nearly identical to Masonic temple rites, and does not specifically involve the feet.[25] In 1843, Smith included a foot washing element in the faith's second anointing ceremony in which elite married couples are anointed as heavenly monarchs and priests.[29]

The observance of washing the saints' feet is quite varied, but a typical service follows the partaking of unleavened bread and wine.[30] Deacons (in many cases) place pans of water in front of pews that have been arranged for the service. The men and women participate in separate groups, men washing men's feet and women washing women's feet. Each member of the congregation takes a turn washing the feet of another member. Each foot is placed one at a time into the basin of water, is washed by cupping the hand and pouring water over the foot, and is dried with a long towel girded around the waist of the member performing the washing. Most of these services appear to be quite moving to the participants.

The True Jesus Church includes footwashing[31] as a scriptural sacrament based on John 13:1–11. Like the other two sacraments, namely Baptism and the Lord's Supper, members of the church believe that footwashing imparts salvific grace to the recipient—in this case, to have a part with Christ (John 13:8).

Most Church of God denominations also include footwashing in their Passover ceremony as instructed by Jesus in John 13:1–11.

Most Seventh-day Adventist congregations schedule an opportunity for foot washing preceding each quarterly (four times a year) Communion service. As with their "open" Communion, all believers in attendance, not just members or pastors, are invited to share in the washing of feet with another: men with men, women with women, and frequently, spouse with spouse. This service is alternatively called the Ordinance of Foot-Washing or the Ordinance of Humility. Its primary purpose is to renew the cleansing that only comes from Christ, but secondarily to seek and celebrate reconciliation with another member before Communion/the Lord's Supper.[32]

Progressive Judaism[]

A number of Jewish rabbis who disagree with the initiation custom of brit milah, or circumcision of a male baby, instead have offered brit shalom, or a multi-part naming ceremony which eschews circumcision. One portion of the ritual, Brit rechitzah, involves the washing of the baby's feet.

See also[]

- Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet (Tintoretto)

- Washing of feet and farewell (The Last Supper in Christian Art)

- Water and religion

- Ablution in Christianity

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Peter C. Bower (January 2003). The Companion to the Book of Common Worship. Geneva Press. ISBN 9780664502324. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

Maundy Thursday (or le mandé; Thursday of the Mandatum, Latin, commandment). The name is taken from the first few words sung at the ceremony of the washing of the feet, "I give you a new commandment" (John 13:34); also from the commandment of Christ that we should imitate His loving humility in the washing of the feet (John 13:14–17). The term mandatum (maundy), therefore, was applied to the rite of foot-washing on this day.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ritter, Abraham (1857). History of the Moravian Church in Philadelphia: from its foundation in 1742 to the present time : comprising notices, defensive of its founder and patron, Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorff, together with an appendix. Hayes & Zell.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Tuker & Malleson 1897, p. 251.

- ^ Washing of the Feet on Holy Thursday. Catholic Online. 29 March 2006.

- ^ [1] NPR, 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Logos, 28 March 2013.

- ^ Burke, Daniel (21 January 2016). "Pope Francis changes foot-washing rite to include women". CNN.

- ^ The Catholic Church puts one foot forward on the path to including women The Washington Post, 26 March 2016

- ^ E.J. King, The Rule Statutes and Customs of the Hospitallers 1099–1310 (London: Methuen, 1934), p. 39.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1987). The Encyclopedia of American Religions. Gale Research Company. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-8103-2133-5.

- ^ Discipline of the Missionary Methodist Church. Missionary Methodist Church. 2004. p. 7.

- ^ Joseph Edmund Hutton (1909). A History of the Moravian Church. RDMC Publishing. ISBN 9780557008261.

- ^ Jackson, Samuel Macauley (1889). The Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge and Gazetteer. Christian literature Company.

- ^ Manual of Doctrine & Government of the Brethren in Christ Church (PDF)

- ^ Church of the Brethren. "Brethren practices". COB Website. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ For All Who Minister: A Worship Manual for the Church of the Brethren. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press. 1993. pp. 183–226.

- ^ "The Neglected Practice of Foot-washing". The Anabaptist Network. 3 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Ramirez, Frank (4 July 2014). "Learning to wash feet is theme of Brethren Journal Association luncheon". Church of the Brethren Newsline. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "About Us". Mountain View Church of the Brethren. 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "Feetwashing in the Church of the Brethren". The Anabaptist Network. 3 March 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ COB Youth Peace Travel Team 2012 (28 June 2012). "Youth Peace Travel Team goes to National Young Adult Conference 2012!". Church of the Brethren Blog. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ William H. Brackney, Historical Dictionary of the Baptists, Scarecrow Press, USA, 2009, p. 219

- ^ Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2013, p. 50

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gruss, E.C.; Thuet, L.A. (2006). What Every Mormon (And Non-mormon) Should Know. XULON Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-60034-163-2. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Arrington, "Oliver Cowdery's Kirtland, Ohio, 'Sketch Book,'" BYU Studies, Summer 12 [1972]: 416–420; Cook and Backman, Kirtland Elders' Quorum Record, 1836–1841 pp. 1–9.

- ^ Buerger, David John (2002) [1994]. The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship (2nd ed.). Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-176-9. OCLC 52076971.

- ^ Buerger, David John (2001). "The Development of the Mormon Temple Endowment Ceremony". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 34 (1/2): 78. ISSN 0012-2157.

- ^ Buerger 2002, p. 24–26.

- ^ Smith, Joseph (1876). The book of Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Territory, Deseret News Office. p. 292.

- ^ "Foot Washing". Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Ordinance of Foot-Washing", Seventh-day Adventist Church Manual (PDF) (17th ed.). Hagerstown, MD: Secretariat, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 2005. p. 82. ISBN 0-8280-1947-9.

References[]

- Tuker, Mildred Anna Rosalie; Malleson, Hope (1897). The liturgy in Rome: Feasts and functions of the church. The ceremonies of Holy Week. Handbook to Christian and Ecclesiastical Rome. Adam and Charles Black.

- Historical and Informational

- Appalachian Mountain Religion: a History, by Deborah Vansau McCauley (ISBN 0-252-06414-3)

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Charles G. Herbermann, Edward A. Pace, Condé B. Pallen, Thomas J. Shahan, and John J. Wynne, editors

- Eerdman's Handbook to the History of Christianity, Tim Dowley, et al., editors

- Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, Samuel S. Hill, editor

- Foxfire 7, Paul F. Gillespie, editor

- Manners and Customs of Bible Lands, by Fred H. Wight

- Mennonite Encyclopedia (Vol. 2), Cornelius J. Dyck, Dennis D. Martin, et al., editors

- Historical and Theological (con)

- Footwashing by the Master and by the Saints, by Elam J. Daniels

- Manual of Church Order (ch. 6), by J. L. Dagg

- Historical and Theological (pro)

- The Washing of the Saints' Feet, by J. Matthew Pinson (Randall House, 2006, ISBN 0-89265-522-4)

- A Free Will Baptist Handbook: Heritage, Beliefs, and Ministries, by J. Matthew Pinson

- Baptist Doctrine: the Doctrine of Foot Washing, by R. L. Vaughn

- Footwashing in John 13 and the Johannine Community, by John Christopher Thomas

- Washing the Saints' Feet shown to be an Ordinance of Christ, by Joseph Sorsby

See also

- entries such as "Maundy Thursday" in the Catholic Encyclopedia

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feet washing. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Washing of Feet and Hands. |

| Look up maundy or pedilavium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- http://www.separatebaptist.org: In the Articles of Faith, Article Eight is about the Communion and Feetwashing Service.

- Anabaptists and Footwashing – a series of articles on history and current practice among Mennonites, Grace Brethren and Church of the Brethren.

- Bender, Harold S.; Klassen, William (1989). "Feetwashing". In Roth, John D. (ed.). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.

- Footwashing as an act of building community – a Brethren viewpoint

- How to conduct a foot-washing service – a liturgical viewpoint

- Footwashing as a Means of Grace (a United Methodist approach) by Gregory S. Neal

- Mennonite Church (MC); General Conference Mennonite Church (GC) (1995), "Article 13: Foot Washing", Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective

- Washing of the Feet : Hidden Significance of the Gnostic story in the Fourth Gospel

- Primitive Baptist FAQ: Feet Washing

- The Ordinance of Feet Washing – a Churches of God General Conference (Winebrenner) viewpoint

- The Footwashing Ritual and the Sacrament of Holy Orders: A New Look at John 13 – a Catholic viewpoint of the import of footwashing as relates to the sacrament of Holy Orders.

- Washing of Feet on Maundy Thursday Armenian Apostolic Church

- Gaining a Dose Of Humility, One Washed Foot at a Time article from The Washington Post, 2 April 2006

- Ron Graybill (1975). Foot Washing in Early Adventism part 2. Foot Washing Becomes an Established Practice. Review and Herald, May 29, 1975, p. 7

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Barefoot

- Gestures of respect

- Gospel of John

- Hygiene

- Last Supper

- Latter Day Saint ordinances, rituals, and symbolism

- Latter Day Saint temple practices

- Ritual purity in Christianity

- Sacraments

- Water and religion