Phonological history of English close front vowels

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (January 2020) |

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

The close and mid-height front vowels of English (vowels of i and e type) have undergone a variety of changes over time and often vary by dialect.

Developments involving long vowels[]

Until Great Vowel Shift[]

Middle English had a long close front vowel /iː/, and two long mid front vowels: the close-mid /eː/ and the open-mid /ɛː/. The three vowels generally correspond to the modern spellings ⟨i⟩, ⟨ee⟩ and ⟨ea⟩ respectively, but other spellings are also possible. The spellings that became established in Early Modern English are mostly still used today, but the qualities of the sounds have changed significantly.

The /iː/ and /eː/ generally corresponded to similar Old English vowels, and /ɛː/ came from Old English /æː/ or /æːɑ̯/. For other possible histories, see English historical vowel correspondences. In particular, the long vowels sometimes arose from short vowels by Middle English open syllable lengthening or other processes. For example, team comes from an originally-long Old English vowel, and eat comes from an originally-short vowel that underwent lengthening. The distinction between both groups of words is still preserved in a few dialects, as is noted in the following section.

Middle English /ɛː/ was shortened in certain words. Both long and short forms of such words often existed alongside each other during Middle English. In Modern English the short form has generally become standard, but the spelling ⟨ea⟩ reflects the formerly-longer pronunciation.[1] The words that were affected include several ending in d, such as bread, head, spread, and various others including breath, weather, and threat. For example, bread was /brɛːd/ in earlier Middle English, but came to be shortened and rhymed with bed.

During the Great Vowel Shift, the normal outcome of /iː/ was a diphthong, which developed into Modern English /aɪ/, as in mine and find. Meanwhile, /eː/ became /iː/, as in feed, and /ɛː/ of words like meat became /eː/, which later merged with /iː/ in nearly all dialects, as is described in the following section.

Meet–meat merger []

The meet–meat merger or the fleece merger is the merger of the Early Modern English vowel /eː/ (as in meat) into the vowel /iː/ (as in meet).[2][3] The merger was complete in standard accents of English by about 1700.[4]

As noted in the previous section, the Early Modern/New English (ENE) vowel /eː/ developed from Middle English /ɛː/ via the Great Vowel Shift, and ENE /iː/ was usually the result of Middle English /eː/ (the effect in both cases was a raising of the vowel). The merger saw ENE /eː/ raised further to become identical to /iː/ and so Middle English /ɛː/ and /eː/ have become /iː/ in standard Modern English, and meat and meet are now homophones. The merger did not affect the words in which /ɛː/ had undergone shortening (see section above), and a handful of other words (such as break, steak, great) also escaped the merger in the standard accents and so acquired the same vowel as brake, stake, grate. Hence, the words meat, threat (which was shortened), and great now have three different vowels although all three words once rhymed.

The merger results in the FLEECE lexical set, as defined by John Wells. Words in the set that had ENE /iː/ (Middle English /eː/) are mostly spelled ⟨ee⟩ (meet, green, etc.), with a single ⟨e⟩ in monosyllables (be, me) or followed by a single consonant and a vowel letter (these, Peter), sometimes ⟨ie⟩ or ⟨ei⟩ (believe, ceiling), or irregularly (key, people). Most of those that had ENE /eː/ (Middle English /ɛː/) are spelled ⟨ea⟩ (meat, team, eat, etc.), but some borrowed words have a single ⟨e⟩ (legal, decent, complete), ⟨ei⟩, or otherwise (receive, seize, phoenix, quay). There are also some loanwords in which /iː/ is spelled ⟨i⟩ (police, machine, ski), most of which entered the language later.[5]

There are still some dialects in the British Isles that do not have the merger. Some speakers in Northern England have /iː/ or /əɪ/ in the first group of words (those that had ENE /iː/, like meet), but /ɪə/ in the second group (those that had ENE /eː/, like meat). In Staffordshire, the distinction might rather be between /ɛi/ in the first group and /iː/ in the second group. In some (particularly rural and lower-class) varieties of Irish English, the first group has /i/, and the second preserves /eː/. A similar contrast has been reported in parts of Southern and Western England, but it is now rarely encountered there.[6]

In some Yorkshire dialects, an additional distinction may be preserved within the meat set. Words that originally had long vowels, such as team and cream (which come from Old English tēam and Old French creme), may have /ɪə/, and those that had an original short vowel, which underwent open syllable lengthening in Middle English (see previous section), like eat and meat (from Old English etan and mete), have a sound resembling /ɛɪ/, similar to the sound that is heard in some dialects in words like eight and weight that lost a velar fricative).[3]

In Alexander's book (2001)[2] about the traditional Sheffield dialect, the spelling "eigh" is used for the vowel of eat and meat, but "eea" is used for the vowel of team and cream. However, a 1999 survey in Sheffield found the /ɛɪ/ pronunciation to be almost extinct there.[7]

Changes before /r/ and /ə/ []

In certain accents, when the FLEECE vowel was followed by /r/, it acquired a laxer pronunciation. In General American, words like near and beer now have the sequence /ir/, and nearer rhymes with mirror (the mirror–nearer merger). In Received Pronunciation, a diphthong /ɪə/ has developed (and by non-rhoticity, the /r/ is generally lost, unless there is another vowel after it), so beer and near are /bɪə/ and /nɪə/, and nearer (with /ɪə/) remains distinct from mirror (with /ɪ/). Several pronunciations are found in other accents, but outside North America, the nearer–mirror opposition is always preserved. For example, some conservative accents in Northern England have the sequence /iːə/ in words like near, with the schwa disappearing before a pronounced /r/, as in serious.[8]

Another development is that bisyllabic /iːə/ may become smoothed to the diphthong [ɪə] (with the change being phonemic in non-rhotic dialects, so /ɪə/) in certain words, which leads to pronunciations like [ˈvɪəkəl], [ˈθɪətə] and [aɪˈdɪə] for vehicle, theatre/theater and idea, respectively. That is not restricted to any variety of English. It happens in both British English and (less noticeably or often) American English as well as other varieties although it is far more common for Britons. The words that have [ɪə] may vary depending on dialect. Dialects that have the smoothing usually also have the diphthong [ɪə] in words like beer, deer, and fear, and the smoothing causes idea, Korea, etc. to rhyme with those words.[9]

Other changes[]

In Geordie, the FLEECE vowel undergoes an allophonic split, with the monophthong [iː] being used in morphologically-closed syllables (as in freeze [fɹiːz]) and the diphthong [ei] being used in morphologically-open syllables not only word-finally (as in free [fɹei]) but also word-internally at the end of a morpheme (as in frees [fɹeiz]).[10][11]

Most dialects of English turn /iː/ into a diphthong, and the monophthongal [iː] is in free variation with the diphthongal [ɪi ~ əi] (with the former diphthong being the same as Geordie [ei], the only difference lying in the transcription), particularly word-internally. However, word-finally, diphthongs are more common.

Compare the identical development of the close back GOOSE vowel.

Developments involving short vowels[]

Lowering[]

Middle English short /i/ has developed into a lax, near-close near-front unrounded vowel, /ɪ/, in Modern English, as found in words like kit. (Similarly, short /u/ has become /ʊ/.) According to Roger Lass, the laxing occurred in the 17th century, but other linguists have suggested that it took place potentially much earlier.[12]

The short mid vowels have also undergone lowering and so the continuation of Middle English /e/ (as in words like dress) now has a quality closer to [ɛ] in most accents. Again, however, it is not clear whether the vowel already had a lower value in Middle English.[13]

Pin–pen merger[]

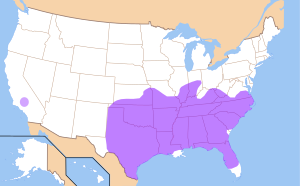

The pin–pen merger is a conditional merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ before the nasal consonants [m], [n], and [ŋ].[14][15][16][17][18] The merged vowel is usually closer to [ɪ] than to [ɛ]. Examples of homophones resulting from the merger include pin–pen, kin–ken and him–hem. The merger is widespread in Southern American English and is also found in many speakers in the Midland region immediately north of the South and in areas settled by migrants from Oklahoma and Texas who settled in the Western United States during the Dust Bowl. It is also a characteristic of African-American Vernacular English.

The pin–pen merger is one of the most widely recognized features of Southern speech. A study[16] of the written responses of American Civil War veterans from Tennessee, together with data from the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States and the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle South Atlantic States, shows that the prevalence of the merger was very low up to 1860 but then rose steeply to 90% in the mid-20th century. There is now very little variation throughout the South in general except that Savannah, Austin, Miami, and New Orleans are excluded from the merger.[18] The area of consistent merger includes southern Virginia and most of the South Midland and extends westward to include much of Texas. The northern limit of the merged area shows a number of irregular curves. Central and southern Indiana is dominated by the merger, but there is very little evidence of it in Ohio, and northern Kentucky shows a solid area of distinction around Louisville.

Outside the South, most speakers of North American English maintain a clear distinction in perception and production. However, in the West, there is sporadic representation of merged speakers in Washington, Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado. However, the most striking concentration of merged speakers in the west is around Bakersfield, California, a pattern that may reflect the trajectory of migrant workers from the Ozarks westward.

The raising of /ɛ/ to /ɪ/ was formerly widespread in Irish English and was not limited to positions before nasals. Apparently, it came to be restricted to those positions in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. The pin–pen merger is now commonly found only in Southern and South-West Irish English.[19][20]

A complete merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/, not restricted to positions before nasals, is found in many speakers of Newfoundland English. The pronunciation in words like bit and bet is [ɪ], but before /r/, in words like beer and bear, it is [ɛ].[21] The merger is common in Irish-settled parts of Newfoundland and is thought to be a relic of the former Irish pronunciation.[22]

Kit–bit split[]

The kit–bit split is a split of standard English /ɪ/ (the KIT vowel) that occurs in South African English. The two distinct sounds are:

- A standard [ɪ], or [i] in broader accents, which is used before or after a velar consonant (lick, big, sing; kiss, kit, gift), after /h/ (hit), word-initially (inn), generally before /ʃ/ (fish), and by some speakers before /tʃ, dʒ/ (ditch, bridge). It is found only in stressed syllables (in the first syllable of chicken, but not the second).

- A centralized vowel [ɪ̈], or [ə] in broader accents, which is used in other positions (limb, dinner, limited, bit).

Different phonemic analyses of these vowels are possible. In one view, [ɪ] and [ɪ̈] are in complementary distribution and should therefore still be regarded as allophones of one phoneme. Wells, however, suggests that the non-rhyming of words like kit and bit, which is particularly marked in the broader accents, makes it more satisfactory to consider [ɪ̈] to constitute a different phoneme from [ɪ ~ i], and [ɪ̈] and [ə] can be regarded as comprising a single phoneme except for speakers who maintain the contrast in weak syllables. There is also the issue of the weak vowel merger in most non-conservative speakers, which means that rabbit /ˈræbət/ (conservative /ˈræbɪt/) rhymes with abbott /ˈæbət/.[23] This weak vowel is consistently written ⟨ə⟩ in South African English dialectology, regardless of its precise quality.

Thank–think merger[]

The thank–think merger is the lowering of /ɪ/ to /æ/ before the velar nasal /ŋ/ that can be found in the speech of speakers of African American Vernacular English, Appalachian English, and (rarely) Southern American English. For speakers with the lowering, think and thank, sing and sang etc. can sound alike.[24] It is reflected in the colloquial variant spelling thang of thing.

Developments involving weak vowels[]

Weak vowel merger[]

The weak vowel merger is the loss of contrast between /ə/ (schwa) and unstressed /ɪ/, which occurs in certain dialects of English: notably Southern Hemisphere, North American, many 21st-century (but not older) standard Southern British, and Irish accents. In speakers with this merger, the words abbot and rabbit rhyme, and Lennon and Lenin are pronounced identically, as are addition and edition. However, it is possible among these merged speakers (such as General American speakers) that a distinction is still maintained in certain contexts, such as in the pronunciation of Rosa's versus roses, due to the morpheme break in Rosa's. (Speakers without the merger generally have [ɪ] in the final syllables of rabbit, Lenin, roses and the first syllable of edition, distinct from the schwa [ə] heard in the corresponding syllables of abbot, Lennon, Rosa's and addition.) If an accent with the merger is also non-rhotic, then for example chatted and chattered will be homophones. The merger also affects the weak forms of some words, causing unstressed it, for instance, to be pronounced with a schwa, so that dig it would rhyme with bigot.[25]

The merger is very common in the Southern Hemisphere accents. Most speakers of Australian English (as well as recent Southern England English)[26] replace weak /ɪ/ with schwa , although in -ing the pronunciation is frequently [ɪ]; and where there is a following /k/, as in paddock or nomadic, some speakers maintain the contrast, while some who have the merger use [ɪ] as the merged vowel. In New Zealand English the merger is complete, and indeed /ɪ/ is very centralized even in stressed syllables, so that it is usually regarded as the same phoneme as /ə/. In South African English most speakers have the merger, but in more conservative accents the contrast may be retained (as [ɪ̈] vs. [ə]. Plus a kit split exists; see above).[27]

The merger is also commonly found in American and Canadian English; however, the realization of the merged vowel varies according to syllable type, with [ə] appearing in word-final or open-syllable word-initial positions (such as drama or cilantro), but often [ɪ~ɨ] in other positions (abbot and exhaust). In traditional Southern American English, the merger is generally not present, and /ɪ/ is also heard in some words that have schwa in RP, such as salad. In Caribbean English schwa is often not used at all, with unreduced vowels being preferred, but if there is a schwa, then /ɪ/ remains distinct from it.[28]

In traditional RP, the contrast between /ə/ and weak /ɪ/ is maintained; however, this may be declining among modern standard speakers of southern England, who increasingly prefer a merger, specifically with the realization [ə].[26] In other accents of the British Isles behavior may be variable; in Irish English the merger is almost universal.[29]

The merger is not complete in Scottish English, where speakers typically distinguish except from accept, but the latter can be phonemicized with an unstressed STRUT: /ʌkˈsɛpt/ (as can the word-final schwa in comma /ˈkɔmʌ/) and the former with /ə/: /əkˈsɛpt/. In other environments KIT and COMMA are mostly merged to a quality around [ə], often even when stressed (Wells transcribes this merged vowel with ⟨ɪ⟩. Here, ⟨ə⟩ is used for the sake of consistency and accuracy) and when before /r/, as in fir /fər/ and letter /ˈlɛtər/ (but not fern /fɛrn/ and fur /fʌr/ - see nurse mergers). The HAPPY vowel is /e/: /ˈhape/.[30]

Even in accents that do not have the merger, there may be certain words in which traditional /ɪ/ is replaced by /ə/ by many speakers (here the two sounds may be considered to be in free variation). In RP, /ə/ is now often heard in place of /ɪ/ in endings such as -ace (as in palace), -ate (as in senate), -less, -let, for the ⟨i⟩ in -ily, -ity, -ible, and in initial weak be-, de-, re-, and e-.[31]

Final /əl/, and also /ən/ and /əm/, are commonly realized as syllabic consonants. In accents without the merger, use of /ɪ/ rather than /ə/ prevents syllabic consonant formation. Hence in RP, for example, the second syllable of Barton is pronounced as a syllabic [n̩], while that of Martin is [ɪn].

Particularly in American linguistic tradition, the unmerged weak [ɪ]-type vowel is often transcribed with the barred i ⟨ɨ⟩, the IPA symbol for the close central unrounded vowel.[32] Another symbol sometimes used is ⟨ᵻ⟩, the non-IPA symbol for a near-close central unrounded vowel; in the third edition of the OED this symbol is used in the transcription of words (of the types listed above) that have free variation between /ɪ/ and /ə/ in RP.

Merger of kit with the word-internal schwa[]

The merger of /ɪ/ with the word-internal variety of /ə/ in abbot (not called COMMA on purpose, since word-final and sometimes also word-initial COMMA can be analyzed as STRUT - see above), which in non-rhotic varieties also encompasses the unstressed syllable of letters occurs when the stressed variant of /ɪ/ is realized with a schwa-like quality [ə], for example in some Inland Northern American English varieties (where the final stage of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift has been completed), New Zealand English, Scottish English and partially also South African English (see kit-bit split). As a result, the vowels in kit /kət/, lid /ləd/, and miss /məs/ belong to the same phoneme as the unstressed vowel in balance /ˈbæləns/.[33][34]

It typically co-occurs with the weak vowel merger, but in Scotland the weak vowel merger is not complete; see above.[35][36]

There are no homophonous pairs apart from those caused by the weak vowel merger, but a central KIT tends to sound like STRUT to speakers of other dialects, which is why Australians accuse New Zealanders of saying "fush and chups" instead of "fish and chips" (which, in an Australian accent, sounds close to "feesh and cheeps"). This is not accurate, as the STRUT vowel is always more open than the central KIT; in other words, there is no strut-comma merger (though a is possible in some Glaswegian speech in Scotland).[37][38] This means that varieties of English with this merger effectively contrast two stressable unrounded schwas, which is very similar to the contrast between /ɨ/ and /ə/ in Romanian, as in the minimal pair rău /rɨw/ 'river' vs. râu /rəw/ 'bad'.

Most dialects with this merger feature happy tensing, which means that pretty is best analyzed as /ˈprətiː/ in those accents. In Scotland, the HAPPY vowel is commonly a close-mid [e], identified phonemically as FACE: /ˈprəte/.

The name kit-comma merger is appropriate in the case of those dialects in which the quality of STRUT is far removed from [ɐ] (the word-final allophone of /ə/), such as Inland Northern American English. It can be misleading in the case of other accents.

Happy tensing []

Happy tensing is a process whereby a final unstressed i-type vowel becomes tense [i] rather than lax [ɪ]. That affects the final vowels of words such as happy, city, hurry, taxi, movie, Charlie, coffee, money, Chelsea. It may also apply in inflected forms of such words containing an additional final consonant sound, such as cities, Charlie's and hurried. It can also affect words such as me, he and she when used as clitics, as in show me, would he?[39]

Until the 17th century, words like happy could end with the vowel of my (originally [iː] but diphthongized in the Great Vowel Shift), it alternated with a short i sound, which led to the present-day realizations. (Many words spelt -ee, -ea, -ey formerly had the vowel of day; there is still alternation between that vowel and the happy vowel in words such as Sunday, Monday.)[40] It is not entirely clear when the vowel underwent the transition. The fact that tensing is uniformly present in South African English, Australian English, and New Zealand English implies that it was present in southern British English already at the beginning of the 19th century. Yet it is not mentioned by descriptive phoneticians until the early 20th century, and even then at first only in American English. The British phonetician Jack Windsor Lewis[41] believes that the vowel moved from [i] to [ɪ] in Britain the second quarter of the 19th century before reverting to [i] in non-conservative British accents towards the last quarter of the 20th century.

Conservative RP has the laxer [ɪ] pronunciation. This is also found in Southern American English, in much of the north of England, and in Jamaica. In Scottish English an [e] sound, similar to the Scottish realization of the vowel of day, may be used. The tense [i] variant, however, is now established in General American, and is also the usual form in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, in the south of England and in some northern cities (e.g. Liverpool, Newcastle). It is also becoming more common in modern RP.[42]

The lax and tense variants of the happy vowel may be identified with the phonemes /ɪ/ and /iː/ respectively. They may also be considered to represent a neutralization between the two phonemes, although for speakers with the tense variant, there is the possibility of contrast in such pairs as taxis and taxes (see English phonology – vowels in unstressed syllables). Modern British dictionaries represent the happy vowel with the symbol ⟨i⟩ (distinct from both ⟨ɪ⟩ and ⟨iː⟩).

Roach (2009) considers the tensing to be a neutralization between /ɪ/ and /iː/,[43] while Cruttenden (2014) regards the tense variant in modern RP still as an allophone of /ɪ/ on the basis that it is shorter and more resistant to diphthongization than /iː/.[44] Lindsey (2019) regards the phenomenon to be a mere substitution of /iː/ for /ɪ/ and criticizes the notation ⟨i⟩ for causing "widespread belief in a specific 'happY vowel'" that "never existed".[45]

Merger of /y/ with /i/ and /yː/ with /iː/[]

Old English had the short vowel /y/ and long vowel /yː/, which were spelled orthographically with ⟨y⟩, contrasting with the short vowel /i/ and the long vowel /iː/, which were spelled orthographically with ⟨i⟩. By Middle English the two vowels /y/ and /yː/ merged with /i/ and /iː/, leaving only the short-long pair /i/-/iː/. Modern spelling therefore uses both ⟨y⟩ and ⟨i⟩ for the modern KIT and PRICE vowels. Modern spelling with ⟨i⟩ vs. ⟨y⟩ is not an indicator of the Old English distinction between the four sounds, as spelling has been revised since after the merger occurred. After the merger occurred, the name of the letter ⟨y⟩ acquired an initial [w] sound in it, to keep it distinct from the name of the letter ⟨i⟩.[citation needed]

Additional mergers in Asian and African English[]

The mitt–meet merger is a phenomenon occurring in Malaysian English and Singaporean English in which the phonemes /iː/ and /ɪ/ are both pronounced /i/. As a result, pairs like mitt and meet, bit and beat, and bid and bead are homophones.[46]

The met–mat merger is a phenomenon occurring in Malaysian English, Singaporean English and Hong Kong English in which the phonemes /ɛ/ and /æ/ are both pronounced /ɛ/. For some speakers, it occurs only in front of voiceless consonants, and pairs like met, mat, bet, bat are homophones, but bed, bad or med, mad are kept distinct. For others, it occurs in all positions.[46]

The met–mate merger is a phenomenon occurring for some speakers of Zulu English in which /eɪ/ and /ɛ/ are both pronounced /ɛ/. As a result, the words met and mate are homophonous as /mɛt/.[47]

See also[]

- Phonological history of the English language

- Phonological history of English vowels

References[]

- ^ Barber, C. L. (1997). Early Modern English. Edinburgh University Press. p. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alexander, D. (2001). Orreight mi ol'. Sheffield: ALD. ISBN 978-1-901587-18-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wakelin, M. F. (1977). English Dialects: An Introduction. London: The Athlone Press.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 195

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 140–141.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 196, 357, 418, 441.

- ^ Stoddart, J.; Upton, C.; Widdowson, J. D. A. (1999). "Sheffield Dialect in the 1990s". In Foulks, P.; Docherty, G. (eds.). Urban Voices: Accent Studies in the British Isles. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 72–89.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 153, 361.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 153.

- ^ Watt, Dominic; Allen, William (2003), "Tyneside English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 267–271, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001397

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 375.

- ^ Stockwell, R.; Minkova, D. (2002). "Interpreting the Old and Middle English close vowels". Language Sciences. 24 (3–4): 447–457. doi:10.1016/S0388-0001(01)00043-2.

- ^ McMahon, A., Lexical Phonology and the History of English, CUP 2000, p. 179.

- ^ Kurath, Hans; McDavid, Raven I. (1961). The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8173-0129-3.

- ^ Morgan, Lucia C. (1969). "North Carolina accents". Southern Speech Journal. 34 (3): 223–29. doi:10.1080/10417946909372000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Vivian Ruby (1990). The social and linguistic history of a merger: /i/ and /e/ before nasals in Southern American English (PhD thesis). Texas A & M University. OCLC 23527868.

- ^ Brown, Vivian (1991). "Evolution of the merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ before nasals in Tennessee". American Speech. Duke University Press. 66 (3): 303–15. doi:10.2307/455802. JSTOR 455802.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-016746-7. OCLC 181466123.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 423.

- ^ Hickey, R. (2004). A Sound Atlas of Irish English. Walter de Gruyter. p. 33.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 500.

- ^ Clarke, S. (2005). "The legacy of British and Irish English in Newfoundland". In Hickey, R. (ed.). Legacies of Colonial English. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-521-83020-6.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 612–3.

- ^ Rickford, John R. (1999). "Phonological and grammatical features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE)" (PDF). African American Vernacular English. Malden, MA & Oxford, UK: Blackwell. pp. 3–14.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 167.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lindsey (2019), pp. 109–145.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 601, 606, 612.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 550, 571, 612.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 167, 427.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 405.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 296.

- ^ Flemming, E.; Johnson, S. (2007). "Rosa's roses: reduced vowels in American English". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 37 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1121/1.4783597.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 404, 606, 612–613.

- ^ Bauer et al. (2007), pp. 98–99, 101.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 405, 605–606, 612–613.

- ^ Bauer et al. (2007), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 403, 607, 615.

- ^ Bauer et al. (2007), pp. 98, 101.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 165–166, 257.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 165.

- ^ "Changes in British English pronunciation during the twentieth century", Jack Windsor Lewis personal website. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 165, 294.

- ^ Roach (2009), p. 67.

- ^ Cruttenden (2014), p. 84.

- ^ Lindsey (2019), p. 32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tony T. N. Hung, English as a global language: Implications for teaching. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Rodrik Wade, MA Thesis, Ch 4: Structural characteristics of Zulu English". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Bibliography[]

- Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul; Bardsley, Dianne; Kennedy, Marianna; Major, George (2007). "New Zealand English". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 37 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1017/S0025100306002830.

- Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72174-5.

- Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W., eds. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110175320.

- Lindsey, Geoff (2019). English After RP: Standard British Pronunciation Today. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-04356-8.

- Roach, Peter (2009). English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71740-3.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 1: An Introduction (pp. i–xx, 1–278), Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Volume 3: Beyond the British Isles (pp. i–xx, 467–674). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52129719-2, 0-52128540-2, 0-52128541-0.

- English phonology

- History of the English language

- Splits and mergers in English phonology