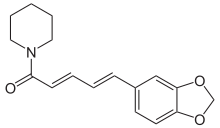

Piperine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(2E,4E)-5-(2H-1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(piperidin-1-yl)penta-2,4-dien-1-one | |

| Other names

(2E,4E)-5-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1-(piperidin-1-yl)penta-2,4-dien-1-one

Piperoylpiperidine Bioperine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.135 |

IUPHAR/BPS

|

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

Chemical formula

|

C17H19NO3 |

| Molar mass | 285.343 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.193 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 130 °C (266 °F; 403 K) |

| Boiling point | Decomposes |

| 40 mg/l | |

| Solubility in alcohol | 1 g/15 ml |

| Solubility in ether | 1 g/36 ml |

| Solubility in chloroform | 1 g/1.7 ml |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | MSDS for piperine |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

| Piperine | |

|---|---|

| Heat | |

| Scoville scale | 100,000 SHU |

Piperine, along with its isomer chavicine, is the compound responsible for the pungency of black pepper and long pepper. It has been used in some forms of traditional medicine.[1]

Preparation[]

Due to its poor solubility in water, piperine is typically extracted from black pepper by using organic solvents like dichloromethane.[2] The amount of piperine varies from 1–2% in long pepper, to 5–10% in commercial white and black peppers.[3][4]

Piperine can also be prepared by treating a concentrated alcoholic extract of black pepper with an alcoholic solution of potassium hydroxide to remove resin (said[by whom?] to contain chavicine, an isomer of piperine). The solution is decanted from the insoluble residue and left to stand overnight. During this period, the alkaloid slowly crystallizes from the solution.[5]

Piperine has been synthesized by the action of piperoyl chloride on piperidine.[4]

Reactions[]

Piperine forms salts only with strong acids. The platinichloride B4·H2PtCl6 forms orange-red needles ("B" denotes one mole of the alkaloid base in this and the following formula). Iodine in potassium iodide added to an alcoholic solution of the base in the presence of a little hydrochloric acid gives a characteristic periodide, B2·HI·I2, crystallizing in steel-blue needles with melting point 145 °C.[4]

Piperine can be hydrolyzed by an alkali into piperidine and piperic acid.[4]

History[]

Piperine was discovered in 1819 by Hans Christian Ørsted, who isolated it from the fruits of Piper nigrum, the source plant of both black and white pepper.[6] Piperine was also found in Piper longum and Piper officinarum (Miq.) C. DC. (=Piper retrofractum Vahl), two species called "long pepper".[7]

Biochemistry and medicinal aspects[]

A component of pungency by piperine results from activation of the heat- and acidity-sensing TRPV ion channels, TRPV1 and TRPA1, on nociceptors, the pain-sensing nerve cells.[8] Piperine is under preliminary research for its potential to affect bioavailability of other compounds in food and dietary supplements, such as a possible effect on the bioavailability of curcumin.[9]

See also[]

- Piperidine, a cyclic six-membered amine that results from hydrolysis of piperine

- Piperic acid, the carboxylic acid also derived from hydrolysis of piperine

- Capsaicin, the active piquant chemical in chili peppers

- Allyl isothiocyanate, the active piquant chemical in mustard, radishes, horseradish, and wasabi

- Allicin, the active piquant flavor chemical in raw garlic and onions (see those articles for discussion of other chemicals in them relating to pungency, and eye irritation)

- Ilepcimide

- Piperlongumine

References[]

- ^ Srinivasan, K. (2007). "Black pepper and its pungent principle-piperine: A review of diverse physiological effects". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 47 (8): 735–748. doi:10.1080/10408390601062054. PMID 17987447. S2CID 42908718.

- ^ Epstein, William W.; Netz, David F.; Seidel, Jimmy L. (1993). "Isolation of Piperine from Black Pepper". J. Chem. Educ. 70 (7): 598. Bibcode:1993JChEd..70..598E. doi:10.1021/ed070p598.

- ^ "Pepper". Tis-gdv.de. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Henry, Thomas Anderson (1949). "Piperine". The Plant Alkaloids (4th ed.). The Blakiston Company. p. 1-2.

- ^ Ikan, Raphael (1991). Natural Products: A Laboratory Guide (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 0123705517.

- ^ Ørsted, Hans Christian (1820). "Über das Piperin, ein neues Pflanzenalkaloid" [On piperine, a new plant alkaloid]. Schweiggers Journal für Chemie und Physik (in German). 29 (1): 80–82.

- ^ Friedrich A. Fluckiger; Daniel Hanbury (1879). Pharmacographia : a History of the Principal Drugs of Vegetable Origin, Met with in Great Britain and British India. London: Macmillan. p. 584. ASIN B00432KEP2.

- ^ McNamara, F. N.; Randall, A.; Gunthorpe, M. J. (March 2005). "Effects of piperine, the pungent component of black pepper, at the human vanilloid receptor (TRPV1)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 144 (6): 781–790. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706040. PMC 1576058. PMID 15685214.

- ^ Kunnumakkara, A. B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N. K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B. B. (2017). "Curcumin, the Golden Nutraceutical: Multitargeting for Multiple Chronic Diseases". British Journal of Pharmacology. 174 (11): 1325–1348. doi:10.1111/bph.13621. PMC 5429333. PMID 27638428.

- Piperidine alkaloids

- Pungent flavors

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- Carboxamides

- Benzodioxoles

- Polyenes

- Enones