Protected designation of origin

Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) is the name, in English, of an identification form used by the European Union and the United Kingdom aimed at preserving the designations of origin of food-related products. The designation was created in 1992 and its main purpose is to designate products that have been produced, processed and developed in a specific geographical area, using the recognized know-how of local producers and ingredients from the region concerned.[1]

The list below also shows other Geographic Indications.

Features[]

The characteristics of the products protected are essentially linked to the terroir. The European or UK PDO logo, of which the use is compulsory, ensures this identification.[2] The European Regulation n.o 510/2006 of March 20, 2006 acknowledges a priority to establish a community protection system guaranteeing equal conditions of competition between producers. This European regulation should guarantee the reputation of regional products, adapt existing national protections to make them comply with the requirements of the World Trade Organization and inform consumers that products bearing the logo of protected designation of origin respect the conditions of production and origin specified by this designation. This regulation concerns certain agricultural products and foodstuffs for which there is a link between the characteristics of the product or the foodstuff and its geographical origin: it may be wines, cheeses, hams, sausages, olives, beers, fruits, vegetables, breads or animal feed.[3][1][4]

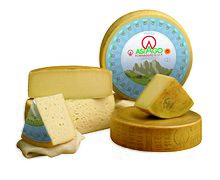

Foods such as gorgonzola, parmigiano-reggiano, asiago cheese, camembert de Normandie and champagne can be labeled as such if they come only from the designated region. For example, to be marketed under the designation of origin "Roquefort,"[5] the cheese must be processed from raw milk from a certain breed of sheep (Lacaune), the animals will be raised in a specific territory and the cheese obtained will be refined in one of the cellars of the village of Roquefort-sur-Soulzonin the French department of Aveyron, where it will be seeded with mold spores (Penicillium roqueforti) prepared from traditional strains endemic to these same cellars.[2]

PDO in different languages[]

The PDO logo is available in all languages of the European Union. Examples of different language versions are shown below:

- German protected designation of origin (PDO)

- French appellation d'origine protégée (AOP)

- Greek προστατευόμενη ονομασία προέλευσης (ΠΟΠ) Prostatevomeni Onomasia Proelefsis (POP)

- Italian Denominazione d'Origine Protetta (DOP)

- Polish chroniona nazwa pochodzenia (CNP)

- Portuguese Denominação de Origem Protegida (DOP)

- Spanish denominación de origen protegida (DOP)

European register[]

The protected names are entered in the European "Register of Protected Designations of Origin and Protected Geographical Indications", or "EU Quality Register" for short, which is maintained by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development.[6] The applications, publications, registrations and any changes are recorded in the DOOR (Database of Origin and Registration) database and can be accessed online by anyone.[7]

Starting on April 1, 2019, the online database eAmbrosia was put into operation by the European Commission, which lists information about protected wines, spirits and food in the European Union and the previous three different databases: E-SPIRIT-DRINKS, DOOR and E -BACCHUS replaced on December 31, 2019.[8]

Lists of PDO products by country[]

Austria[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sura Kees | Montafon valley in Vorarlberg (Austria) | Sura Kees (Alemannic: "sour cheese"), also known as Vorarlberger Sauerkäse or Montafoner Sauerkäse is a low-fat sour milk cheese originally from the Montafon valley in Vorarlberg (Austria). It is traditionally made from skim milk and is a by-product of butter production. Sura Kees resembles the Tyrolean Grey Cheese. The registration of the PDO states that its production has been a significant element of Vorarlberg's peasant gastronomy for centuries. Sura Kees is usually served with vinegar, oil and onions, pure on black bread or eaten with potatoes.[9] |  Sura-Kees |

| Tyrolean grey cheese | Tyrolean Alp valleys (Austria). | Tyrolean grey cheese (Graukäse) is a strongly flavoured, rennet-free cows-milk acid-curd cheese made in the Tyrolean Alp valleys, Austria. It owes its name to the grey mold that usually grows on its rind. It is extremely low in fat (around 0.5%) and it has a powerful penetrating smell. The cheese is registered as protected designation of origin under the official name Tiroler Graukäse g.U.[10] The registration of the PDO states that its production has been a significant element of Tyrolean peasant gastronomy for centuries. Graukäse making became widespread on farms due to the simplicity of making and the availability of low-fat milk after the fat had been taken for use in butter making.[11] |  Tyrolean grey cheese Loaf Cut |

| Tyrolean Speck | Tyrol | Tyrolean Speck is a distinctively juniper-flavored ham originally from Tyrol, a historical region that since 1918 partially lies in Italy. Its origins at the intersection of two culinary worlds is reflected in its synthesis of salt-curing and smoking. The first historical mention of Tyrolean Speck was in the early 13th century when some of the current production techniques were already in use. Südtiroler Speck (Italian: Speck Alto Adige) is now a protected geographic designation with PGI status.[12] |  Speck |

| Vorarlberger Bergkäse | Vorarlberg | Vorarlberger Bergkäse ("Vorarlberg mountain cheese") is a regional cheese specialty from the Austrian state of Vorarlberg. It is protected within the framework of the European designation of origin (PDO).[13][14] |  2014-12-08 Bergkäse Milfina 5710 |

Belgium[]

In Belgium, since 2011, the Public Service of Wallonia, the Quality Department of the Operational Directorate-General for Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Environment (DGARNE), has set up CAIG; a program dedicated to geographical indication of produce.[15] This project is carried out jointly by the University of Liège (Laboratory for Quality and Safety of Agrifood Products, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech[16]) and the University of Namur (Department of History, Pole of Environmental History[17]). The objective of the CAIG is to support the Walloon producer groups wishing to submit an application for recognition of their product as a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) or Traditional Specialty Guaranteed (TSG). To do this, CAIG supports producers in their process of drafting specifications and in the work of characterizing the product.

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beurre d'Ardenne | Ardenne | Beurre d’Ardenne is a type of butter made in the Ardenne of Belgium from cow's milk. As a traditional product of the area, it received Belgian appellation d'origine by royal decree in 1984,[18] and received European protected designation of origin status in 1996.[19] | |

| Framboise | Belgium | Framboise is used primarily in reference to a Belgian lambic beer that is fermented using raspberries.[20] It is one of many modern types of fruit beer that have been inspired by the more traditional kriek beer, which is made using sour cherries. |  Timmermans framboise |

| Gueuze | Belgium | Gueuze (Dutch geuze, pronounced [ˈɣøzə];[21][22] French gueuze, [ɡøz][23]) is a type of lambic, a Belgian beer. It is made by blending young (1-year-old) and old (2- to 3-year-old) lambics, which is bottled for a second fermentation. Because the young lambics are not fully fermented, the blended beer contains fermentable sugars, which allow a second fermentation to occur. |  Gueze Boon |

| Kriek lambic | Brussels | Kriek lambic is a style of Belgian beer, made by fermenting lambic with sour Morello cherries. Traditionally "Schaarbeekse krieken" (a rare Belgian Morello variety) from the area around Brussels are used. As the Schaarbeek type cherries have become more difficult to find, some brewers have replaced these (partly or completely) with other varieties of sour cherries, sometimes imported.[24] |  Kriek Beer |

| Lambic | Brussels | Lambic (English: /lɒ̃bikˌ ˈlæmbɪk/) is a type of beer brewed in the Pajottenland region of Belgium southwest of Brussels and in Brussels itself since the 13th century.[25] Types of lambic beers include gueuze, kriek lambic and framboise.[26] Lambic differs from most other beers in that it is fermented through exposure to wild yeasts and bacteria native to the Zenne valley, as opposed to exposure to carefully cultivated strains of brewer's yeast. This process gives the beer its distinctive flavour: dry, vinous, and cidery, often with a tart aftertaste.[27] |  A glass and bottle of Boon Faro |

United Kingdom[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbroath smokie | Arbroath | The Arbroath smokie is a type of smoked haddock – a speciality of the town of Arbroath in Angus, Scotland. The Arbroath smokie is said to have originated in the small fishing village of Auchmithie, three miles northeast of Arbroath.[28] |  Racks of haddock in a homemade smoker. Smouldering at the bottom are hardwood wood chips. The sacking at the back is used to cover the racks while they are smoked. |

| Bonchester cheese | Bonchester Bridge | Bonchester cheese is a soft Scottish cheese, made from unpasteurized Jersey cows' milk.[29] It is produced in Bonchester Bridge, Roxburghshire. | |

| Buxton Blue | Buxton | Buxton Blue is an English blue cheese that is a close relative of Blue Stilton, is made from cow's milk, and is lightly veined with a deep russet colouring.[30] It is usually made in a cylindrical shape. | |

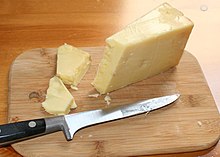

| Cheddar cheese | Cheddar, Somerset | Cheddar cheese, commonly known as cheddar, is a relatively hard, off-white (or orange if colourings such as annatto are added), sometimes sharp-tasting, natural cheese. Originating in the English village of Cheddar in Somerset,[31] cheeses of this style are now produced all over the world. |  Somerset-Cheddar |

| Clotted cream | Devonshire | Clotted cream (Cornish: dehen molys, sometimes called scalded, clouted, Devonshire or Cornish cream) is a thick cream made by indirectly heating full-cream cow's milk using steam or a water bath and then leaving it in shallow pans to cool slowly. During this time, the cream content rises to the surface and forms "clots" or "clouts", hence the name.[32] It forms an essential part of a cream tea. |  Clotted cream (cropped) |

| Comber Earlies | Comber | Comber Earlies, also called new season Comber potatoes,[33] are potatoes grown around the town of Comber, County Down, Northern Ireland.[34] They enjoy the status of protected geographical indication (PGI) since 2012 and are grown by the Comber Earlies Growers Co-Operative Society Limited.[35][36][37][38][39] | |

| Cornish pasty | Cornwall | A pasty (/ˈpæsti/)[40] is a British baked pastry, a traditional variety of which is particularly associated with Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is made by placing an uncooked filling, typically meat and vegetables, on one half of a flat shortcrust pastry circle, folding the pastry in half to wrap the filling in a semicircle and crimping the curved edge to form a seal before baking.

The traditional Cornish pasty, which since 2011 has Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status in Europe,[41] is filled with beef, sliced or diced potato, swede (also known as yellow turnip or rutabaga – referred to in Cornwall as turnip) and onion, seasoned with salt and pepper, and baked. Today, the pasty is the food most associated with Cornwall. It is regarded as the national dish and accounts for 6% of the Cornish food economy. Pasties with many different fillings are made and some shops specialise in selling all sorts of pasties. |

Cornish Pasty |

| Cornish sardine | Cornwall | Since 1997, sardines from Cornwall have been sold as "Cornish sardines", and since March 2010, under EU law, Cornish sardines have Protected Geographical Status. The industry has featured in numerous works of art, particularly by Stanhope Forbes and other Newlyn School artists.[42] | Sardines use body-caudal fin locomotion to swim, and streamline their bodies by holding their other fins flat against the body. |

| Cumberland sausage | Cumberland | Cumberland sausage is a pork sausage that originated in the ancient county of Cumberland, England, now part of Cumbria. It is traditionally very long, up to 50 centimetres (20 inches), and sold rolled in a flat, circular coil, but within western Cumbria, it is more often served in long, curved lengths.[citation needed] Seasonings are prepared from a variety of spices and herbs, though the flavour palate is commonly dominated by pepper, both black and white, in contrast to more herb-dominated varieties such as Lincolnshire sausage. Traditionally no colourings or preservatives are added. The distinctive feature is that the meat is chopped, not ground or minced, giving the sausage a chunky texture. In March 2011, the "Traditional Cumberland sausage" was granted Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status.[43] |  Cumberland sausage |

| Dovedale cheese | Dovedale | Dovedale, sold as Dovedale Blue', is a blue cheese. It is named after the Dovedale valley in the Peak District, near where it is produced. Dovedale is a soft, creamy cheese with a mild blue flavour.[44][45][46] It is made from full fat cow's milk.[44][45][46] Unusually for a British cheese, it is brine dipped, rather than dry-salted, giving it a distinctive continental appearance and flavour.[44][46] In 2007, Dovedale was awarded Protected designation of origin (PDO) status, meaning that it must be traditionally manufactured within 50 miles (80 km) of the Dovedale valley.[45] The original cheese was invented and is still produced at the Hartington Creamery in Derbyshire;[44][47] a version is also produced by the Staffordshire Cheese Company in Cheddleton, Staffordshire.[48] |  Dovedale cheese |

| Gloucester cheese | Gloucester | Gloucester is a traditional, semi-hard cheese which has been made in Gloucestershire, England, since the 16th century. There are two varieties of the cheese, Single and Double; both are traditionally made from milk from Gloucester cattle. Both types have a natural rind and a hard texture, but Single Gloucester is more crumbly, lighter in texture and lower in fat. Double Gloucester is allowed to age for longer periods than Single, and it has a stronger and more savoury flavour. It is also slightly firmer. The flower known as Lady's Bedstraw (Galium verum), was responsible for the distinctively yellow colour of Double Gloucester Cheese.[49][50] |  Double Gloucester cheese |

| Traditional Grimsby smoked fish | Grimsby | Traditional Grimsby smoked fis' are regionally processed fish food products from the British fishing town of Grimsby, England.

Grimsby has long been associated with the sea fishing industry, which once gave the town much of its wealth. At its peak in the 1950s, it was the largest and busiest fishing port in the world.[51] The UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), defines Traditional Grimsby smoked fish "as fillets of cod and haddock, weighing between 200 and 700 grams, which have been cold smoked in accordance with the traditional method and within a defined geographical area around Grimsby.[52] After processing the fish fillets vary from cream to beige in colour, with a characteristic combination of dry textured, slightly salty, and smokey flavour dependent on the type of wood used in the smoking process. Variations in wood quality, smoke time and temperature control the end flavour. The smoking process is controlled by experienced cold smokers trained in the traditional Grimsby method. In 2009, Traditional Grimsby smoked fish was awarded Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status by the European Commission. |

Traditional Grimsby smoked haddock |

| Herdwick | Lake District | The Herdwick is a breed of domestic sheep native to the Lake District in North West England. The name "Herdwick" is derived from the Old Norse herdvyck, meaning sheep pasture.[53] Though low in lambing capacity and perceived wool quality when compared to more common commercial breeds, Herdwicks are prized for their robust health, their ability to live solely on forage, and their tendency to be territorial and not to stray over the difficult upland terrain of the Lake District. It is considered that up to 99% of all Herdwick sheep are commercially farmed in the central and western Lake District.In 2013, Lakeland Herdwick meat received a Protected Designation of Origin from the European Union.[54] |  A Herdwick ewe |

| Jersey Royal | Jersey | The Jersey Royal is the marketing name of a type of potato grown in Jersey which has a Protected Designation of Origin. The potatoes are of the variety known as International Kidney and are typically grown as a new potato.[55] Under the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union Jersey Royals are covered by a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).[56][57] |  'Jersey Royals', boiled |

| Melton Mowbray pork pie | Melton Mowbray | The Melton Mowbray pork pie is named after Melton Mowbray, a town in Leicestershire.[58] While it is sometimes claimed that Melton pies became popular among fox hunters in the area in the late eighteenth century,[59] it has also been stated that the association of the pork pie trade with Melton originated around 1831 as a sideline in a small baker and confectioners' shop in the town, owned by Edward Adcock.[60] Within the next decade a number of other bakers then started supplying them, notably Enoch Evans, a former grocer, who seems to have been particularly responsible for establishing the industry on a large scale.[60] Whether true or not the association with hunting provided valuable publicity, although one local hunting columnist writing in 1872 stated that it was extremely unlikely that "our aristocratic visitors carry lumps of pie with them on horseback". In the light of the premium price of the Melton Mowbray pie, the Melton Mowbray Pork Pie Association applied for protection under European Protected designation of origin laws as a result of the increasing production of Melton Mowbray-style pies by large commercial companies in factories far from Melton Mowbray, and recipes that deviated from the original uncured pork form. Protection was granted on 4 April 2008, with the result that only pies made within a designated zone around Melton (made within a 28 square kilometres (10.8 sq mi) zone around the town), and using the traditional recipe including uncured pork, are allowed to carry the Melton Mowbray name on their packaging.[61][62] |  A Melton Mowbray pork pie |

| Newmarket sausage | Newmarket, Suffolk | The Newmarket sausage is a pork sausage made to a traditional recipe from the English town of Newmarket, Suffolk. Two varieties of Newmarket Sausage are made branded with the names of two different family butchers. Both are sold widely throughout the United Kingdom. In October 2012 the Newmarket sausage was awarded Protected Geographical Indicator of Origin (PGI)[63] status.[64] |  A cooked Newmarket sausage |

| North Ronaldsay sheep | North Ronaldsay | The North Ronaldsay or Orkney is a breed of sheep from North Ronaldsay, the northernmost island of Orkney, off the north coast of Scotland. It belongs to the Northern European short-tailed sheep group of breeds, and has evolved without much cross-breeding with modern breeds. It is a smaller sheep than most, with the rams (males) horned and ewes (females) mostly hornless. It was formerly kept primarily for wool, but now the two largest flocks are feral, one on North Ronaldsay and another on the Orkney island of Auskerry. The Rare Breeds Survival Trust lists the breed as a priority on there 2021-2022 watchlist, and they are in danger of dying out with fewer than 600 registered breeding females in the United Kingdom. The semi-feral flock on North Ronaldsay is the original flock that evolved to subsist almost entirely on seaweed – they are one of few mammals to do this. They are confined to the foreshore by a 1.8 m (6 ft) drystane dyke, which completely encircles the island, forcing the sheep to evolve this unusual characteristic. The wall was built as kelping (the production of soda ash from seaweed) on the shore became uneconomical. Sheep were confined to the shore to protect the fields and crofts inside, and afterwards subsisted largely on seaweed. This diet has caused a variety of adaptations in the sheep's digestive system. These sheep have to extract the trace element copper far more efficiently than other breeds as their diet has a limited supply of copper. This results in them being susceptible to copper toxicity, if fed on a grass diet, as copper is toxic to sheep in high quantities. Grazing habits have also changed to suit the sheep's environment. To reduce the chance of being stranded by an incoming tide, they graze at low tide and then ruminate at high tide. A range of fleece colours are exhibited, including grey, brown and red. Meat from the North Ronaldsay has a distinctive flavour, described as "intense" and "gamey",[65] due, in part, to the high iodine content in their diet of seaweed. The meat has Protected Geographical Status in European Union law, so only meat from North Ronaldsay sheep can be marketed as Orkney Lamb.Lamb meat and mutton from the sheep have been specially designated by the European Union, meaning that only pure-bred lambs can be marketed as "Orkney Lamb".[66] The meat has a unique, rich flavour, which has been described as "intense and almost gamey",[65] and has a darker colour than most mutton, due in part to the animals' iodine-rich diet.[65] |  A North Ronaldsay sheep with twin lambs on the beach, with seals in the background |

| Perry | England | Perry is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears, similar to the way cider is made from apples. It has been common for centuries in England, particularly in the Three Counties (Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire); it is also made in parts of South Wales and France, especially Normandy and Anjou. It is also made in Commonwealth countries such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand.[citation needed] In more recent years, commercial perry has also been referred to as "pear cider", but some organisations (such as CAMRA) do not accept this as a name for the traditional drink.[67] The National Association of Cider Makers, on the other hand, disagrees, insisting that the terms perry and pear cider are interchangeable.[68] An over twenty-fold increase of sales of industrially manufactured "pear cider" produced from often imported concentrate makes the matter especially contentious. |  A traditional perry (poiré in French) bottled under cork and cage from Normandy |

| Plymouth Gin | Plymouth | Plymouth Gin used to be a Protected Geographical Indication that pertained to any gin distilled in Plymouth, England,[69] but this stopped being true in February 2015.[citation needed] Today, there is only one brand, Plymouth, which is produced by the Black Friars Distillery. The Black Friars Distillery is the only remaining gin distillery in Plymouth, in what was once a Dominican Order monastery built in 1431, and opens onto what is now Southside Street. It has been in operation since 1793.[70] The established distilling business of Fox & Williamson began the distilling of the Plymouth brand in 1793. Soon, the business was to become known as Coates & Co., which it remained until March 2004. In 1996, the brand was sold by Allied-Lyons to a management group headed by Charles Rolls who reinvigorated it.[71] After turning the company around, they sold it in 2005 to the Swedish company V&S Group, which also made Absolut Vodka. The brand is now owned and distributed by the French company Pernod Ricard as a result of its purchase of V&S in 2008. |  Mojito in a Plymouth glass |

| Rhubarb Triangle | West Yorkshire | The Rhubarb Triangle (or Tusky Triangle,[72][failed verification] from a Yorkshire word for rhubarb) is a 9-square-mile (23 km2) area of West Yorkshire, England between Wakefield, Morley and Rothwell famous for producing early forced rhubarb. It includes Kirkhamgate, East Ardsley, Stanley, Lofthouse and Carlton.[73] The Rhubarb Triangle was originally much bigger, covering an area between Leeds, Bradford and Wakefield.[74] From the 1900s to 1930s, the rhubarb industry expanded and at its peak covered an area of about 30 square miles (78 km2).[75] Twelve farmers who farm within the Rhubarb Triangle applied to have the name "Yorkshire forced rhubarb" added to the list of foods and drinks that have their names legally protected by the European Commission's Protected Food Name scheme.[76] The application was successful and the farmers in the Rhubarb Triangle[a] were awarded Protected Designation of Origin status (PDO) in February 2010. Food protected status accesses European funding to promote the product and legal backing against other products made outside the area using the name. Other protected names include Stilton cheese, Champagne and Parma Ham. Leeds Central MP, Hilary Benn, was involved in the Defra campaign to win protected status.[77][78] |  Rhubarb Sculpture |

| Shetland sheep | Shetland Isles | The Shetland is a small, wool-producing breed of sheep originating in the Shetland Isles, Scotland but is now also kept in many other parts of the world. It is part of the Northern European short-tailed sheep group, and it is closely related to the extinct Scottish Dunface. Shetlands are classified as a landrace or "unimproved" breed.[79] This breed is kept for its very fine wool, for meat, and for conservation grazing.[80] |  Shetland ewe grazing on heathland: this "badger-faced" pattern is called katmoget. |

| Stilton cheese | Cambridgeshire | Stilton is an English cheese, produced in two varieties: Blue, which has had Penicillium roqueforti added to generate a characteristic smell and taste, and White, which has not. Both have been granted the status of a protected designation of origin (PDO) by the European Commission, requiring that only such cheese produced in the three counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire may be called "Stilton". The cheese takes its name from the village of Stilton, now in Cambridgeshire, where it has long been sold. Stilton cheese cannot be produced in Stilton village, which gave the cheese its name,[81] because it is not in any of the three permitted counties, but in the administrative county of Cambridgeshire and the historic county of Huntingdonshire. The Original Cheese Company applied to Defra to amend the Stilton PDO to include the village, but the application was rejected in 2013.[82] |  Blue Stilton 01 |

| Swaledale cheese | Richmond | Swaledale is a full fat hard cheese produced in the town of Richmond in Swaledale, North Yorkshire, England.[83] The cheese is produced from cows’ milk, Swaledale sheep's milk and goats’ milk.[84] In 1995 Swaledale Cheese and Swaledale Ewes Cheese were awarded European protected designation of origin (PDO) status. Swaledale cheeses have won a number of awards including three gold awards at the 2008 Great Taste Awards and three gold and two bronze medals at 2008 World Cheese Awards.[85][86] |  Swaledale Cheese cowsmilk |

| Teviotdale cheese | Teviotdale | Teviotdale is a full fat hard cheese produced in the area of Teviotdale on the border lands between Scotland and England, within a radius of 90km from the summit of Peel Fell in the Cheviot Hills.[87] The cheese is produced from the milk of the Jersey cattle. There are no known current producers of this cheese. Teviotdale cheese was awarded European Protected Geographical Status (PGI) status. | |

| Wensleydale cheese | Wensleydale | Wensleydale is a style of cheese originally produced in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire, England, but now mostly made in large commercial creameries throughout the United Kingdom. The term "Yorkshire Wensleydale" can only be used for cheese that is made in Wensleydale.[88][89] PGI 2013 (Yorkshire Wensleydale)[90] |  Wensleydale cheese 2 |

Chile[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chilean pisco | Chile | Chilean Pisco must be made in the country's two official D.O. (Denomination of Origin) regions—Atacama and Coquimbo—established in 1931 by the government. Most of it is produced with a "boutique" type of distillate. Other types are produced with double distillation in copper and other materials.[91] |  A selection of popular Chilean piscos |

| Limón de Pica | Pica | Limón de Pica is an unusually acidic lime from the oasis town of Pica in Atacama Desert. Limóns de Pica have had an appellation of origin since 2010.[92] The environment where the limes are grown has a mild microclimate that does not display the typical high temperature oscillations seen in many of the world's deserts/[93] |

China[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yongfeng chili sauce | Yongfeng | Yongfeng chili sauce (Chinese: 永丰辣酱; pinyin: Yǒngfēng làjiàng) or Yongfeng hot sauce[94] is a traditional product made at Yongfeng, Shuangfeng County, Hunan, China.[95] It is recognized by China as a Geographical Indication Product.[96][97] |  Yongfeng chili sauce in fermenting bowls |

Denmark[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danbo | Danemark | Danbo is a semi-soft, is a semi-soft, aged cow's milk cheese from Denmark. It was awarded Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status under European Union law on 2017.[98] The cheese is typically aged between 12 and 52 weeks in rectangular blocks of 6 or 9 kg (13 or 20 lb), coated with a bacterial culture. The culture is washed off at the end of the aging cycle, and the cheese is packaged for retail sales. |  Danbo cheese |

| Danish Blue Cheese | Danemark | Danablu, often marketed under the trademark Danish Blue Cheese within North America,[99] is a strong, blue-veined cheese.[100] This semi-soft creamery cheese is typically drum- or block-shaped and has a yellowish, slightly moist, edible rind. Made from full fat cow's milk and homogenized cream, it has a fat content of 25–30% (50–60% in dry matter) and is aged for eight to twelve weeks.[99] |  Danish Blue cheese |

| Esrom | Esrom | Esrom, or Danish Port Salut cheese is a Trappist-style pale yellow semi-soft cow's milk cheese with a pungent aroma and a full, sweet flavour. It takes its name from the monastery, Esrom Abbey, where it was produced until 1559. The production of modern-style Esrom cheese was standardized at Statens Forsøgsmejeri in the 1930s. The first large-scale production of the cheese was established at Midtsjællands Herregårdsmejeri in the early 1940s. It was one of the most popular Danish cheeses in the 1960s but then almost disappeared. Production of Esrom cheese has been revived by a number of dairy companies in more recent years.[101] |  Esrom cheese |

Finland[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karelian pasty | Karelia | Karelian pasties,Karelian pies or Karelian pirogs (South Karelian dialect of Finnish: karjalanpiirakat, singular karjalanpiirakka; North Karelian dialect of Finnish: karjalanpiiraat, singular karjalanpiiras; Karelian: kalittoja, singular kalitta;[102] Olonets Karelian: šipainiekku; Russian: карельский пирожок karelskiy pirozhok or калитка kalitka; Swedish: karelska piroger) are traditional Finnish pasties or pirogs originating from the region of Karelia. They are eaten throughout Finland as well as in adjacent areas such as Estonia and northern Russia. Karjalanpiirakka has Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG) status in Europe.[103] This means that any product outside of Finland that make a similar product cannot call them karjalanpiirakka and instead call them riisipiirakka ("rice pasties"), perunapiirakka ("potato pasties") etc., depending on the filling.[104] |  Karjalanpiirakka-20060227 |

| Rönttönen | Kainuu | A Rönttönen is a traditional sweet Finnish delicacy from Kainuu. A small (about the size of the palm of a hand) open faced pie consisting of a crust made of barley or rye dough, filled with a sweetened mashed potato and berry (most often Lingonberry) filling.[105] Typically, it is served as an accompaniment to a coffee. The Kainuun rönttönen has a protected geographical indication under the EU law.[106] | |

| Sahti | Finland | Sahti is a Finnish type of farmhouse ale made from malted and unmalted grains including barley and rye. Traditionally the beer is flavored with juniper in addition to, or instead of, hops;[107] the mash is filtered through juniper twigs into a trough-shaped tun, called a kuurna in Finnish. Sahti is top-fermented and many have a banana flavor due to isoamyl acetate from the use of baking yeast, although ale yeast may also be used in fermenting. |  Finlandia Sahti, a Finnish sahti brand |

France[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abondance cheese | Haute-Savoie | Abondance is a semi-hard, fragrant, raw-milk cheese made in the Haute-Savoie department of France. Its name comes from a small commune also called Abondance. A round of Abondance weighs approximately 10 kg (22 lb), and its aroma is comparable to Beaufort, another French cheese variety. Abondance is made exclusively from milk produced by the Abondance, montbéliarde, and tarine breeds of cattle. By 2022, the herd producing the milk for Abondance cheese will need to be a minimum of 55 percent of the herd.[108][clarification needed] In 1998, 873 tonnes were produced (+16.4 percent since 1996), 34 percent from local farms. Abondance cheese was granted an Appellation d'origine contrôlée or AOC in 1990.[109] |  Abondance (cheese) |

| Bayonne ham | Bayonne | Bayonne ham or jambon de Bayonne is a cured ham that takes its name from the ancient port city of Bayonne in the far southwest of France, a city located in both the cultural regions of Basque Country and Gascony. It has PGI status. |  Bayonne ham |

| Beaufort cheese | Savoie | Beaufort (French pronunciation: [bo.fɔʁ]) is a firm, raw cow's milk cheese associated with the gruyère family.[110] An Alpine cheese, it is produced in Beaufortain, Tarentaise valley and Maurienne, which are located in the Savoie region of the French Alps.[111] Beaufort was first certified as an appellation d'origine contrôlée in 1968.[112][113] |  Beaufort |

| Beurre d'Isigny | Isigny-sur-Mer | Beurre d'Isigny is a type of cow's milk butter made in the Veys Bay area and the valleys of the rivers running into it, comprising several French communes surrounding Isigny-sur-Mer and straddling the Manche and Calvados departments of northern France. The butter has a natural golden colour as a result of high levels of carotenoids.[114] The butter contains 82% fatty solids and is rich in oleic acid and mineral salts (particularly sodium). These salts provide flavour and a long shelf-life.[115] cThe local producers requested protection for their milk products as early as the 1930s with a definition of the production area, finally receiving PDO status in 1996.[116] |  Ad for the butter, 1900. |

| Bleu d'Auvergne | Auvergne | Bleu d'Auvergne (French: [blø dovɛʁɲ]) is a French blue cheese, named for its place of origin in the Auvergne region of south-central France.[117] It is made from cow's milk,[118] and is one of the cheeses granted the Appellation d'origine contrôlée from the French government. Bleu d'Auvergne was developed in the mid-1850s by a French cheesemaker named Antoine Roussel.[118] Roussel noted that the occurrence of blue molds on his curd resulted in an agreeable taste, and conducted experiments to determine how veins of such mold could be induced.[118] After several failed tests, Roussel discovered that the application of rye bread mold created the veining, and that pricking the curd with a needle provided increased aeration.[118] The increased oxygenation enabled the blue mold to grow in the pockets of air within the curd.[118] Subsequently, his discovery and techniques spread throughout the region. Today, bleu d'Auvergne is prepared via mechanical needling processes. It is then aged for approximately four weeks in cool, wet cellars before distribution, a relatively short period for blue cheeses. |  Bleu d'Auvergne cheese |

| Boudin blanc de Rethel | Rethel | Boudin blanc de Rethel (pronounced [bu.dɛ̃ blɑ̃ də ʁə.tɛl]): a traditional French boudin, which may only contain pork meat, fresh whole eggs and milk, and cannot contain any breadcrumbs or flours/starches. It is protected under EU law with a Protected geographical indication status.[119][120] |  Boudins noir et blanc au marché de Noël de Bruxelles |

| Brie | Brie | Brie (/briː/; French: [bʁi]) is a soft cow's-milk cheese named after Brie, the French region from which it originated (roughly corresponding to the modern département of Seine-et-Marne). It is pale in color with a slight grayish tinge under a rind of white mould. The rind is typically eaten, with its flavor depending largely upon the ingredients used and its manufacturing environment. It is similar to Camembert, which is native to a different region of France. Brie cheese, like Camembert and Cirrus, is considered a soft cheese.[121] This particular type of cheese is very rich and creamy, unlike Cheddar. This softness allows for the rapid widespread growth of bacteria if the cheese is not stored correctly. It is recommended that brie cheese be refrigerated immediately after purchase, and stored in the refrigerator until it is consumed completely.[122] The optimal storage temperature for brie is 4 °C (39 °F) or even lower. The cheese should be kept in a tightly sealed container or plastic wrap to avoid contact with moisture and food-spoilage bacteria which will reduce the shelf life and freshness of the product.[122] The companies that produce this cheese usually recommend that their cheese be consumed before the best-before date and no later than a week after. Although the cheese can still be consumed at this time, the quality of the cheese is believed to be reduced substantially. In the case that blue or green mould appears to be growing on the cheese, it must no longer be consumed and must be discarded immediately so that food-borne illness is prevented. The mold should not be cut off to continue consumption as there is a high risk of the mold's spores being already spread throughout the entire cheese.[122] |  Brie noir |

| Brie de Meaux | Brie region | Brie de Meaux is a French brie cheese of the Brie region and a designated AOC product since 1980.[123] Its name comes from the town of Meaux in the Brie region. As of 2003, 6,774 tonnes (-13.4% since 1998) were produced annually. |  Brie de Meaux |

| Brocciu | Brocciu is a Corsican cheese produced from a combination of milk and whey,[124] giving it some of the characteristics of whey cheese. It is produced from ewe's milk.[124] It is notable as a substitute for lactose-rich Italian Ricotta, as brocciu contains less lactose.[125] Produced on the island of Corsica, brocciu is considered the island's most representative food. Like ricotta, it is a young white cheese and is paired frequently with Corsican white wines. It has been described as "the most famous cheese" in Corsica.[126] The word brocciu is related to the French word brousse and means fresh cheese made with goat or ewe's milk. Brocciu is made from whey and milk. First, the whey is heated to a low temperature of just a few degrees below 100 °F (38 °C) and then ewe's milk is added and further heated to just a bit below 200 °F (93 °C). After heating, the cheese is drained in rush baskets. The cheese is ready for consumption immediately, although it may be ripened for a few weeks (Corsican: brocciu passu or brocciu vechju); the ideal affinage time for brocciu is 48 hours to one month.[127] In Corsican cuisine, it is used in the preparation of innumerable dishes, from first courses to desserts.[128] |  Brocciu | |

| Camembert | Normandy | Camembert (/ˈkæməmbɛər/, also UK: /-mɒmbɛər/, US: /-məmbərt/,[129][130][131][132] French: [kamɑ̃bɛʁ] ( |

True Camembert de Normandie made with unpasteurized milk |

| Cantal cheese | Auvergne | Cantal cheese is an uncooked firm cheese[133] produced in the Auvergne region of central France: more particularly in the département of Cantal (named after the Cantal mountains) as well as in certain adjoining districts. Cantal cheese was granted Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée certification in 1956.[134] One of the oldest cheeses in France,[135] Cantal dates back to the times of the Gauls. It came to prominence when Marshal Henri de La Ferté-Senneterre served it at the table of Louis XIV of France. Senneterre is also responsible for the introduction of Saint-Nectaire and Salers. Cantal, Auvergne AOC, 1956.[136] |  Cantal 03 |

| Chabichou | France | Chabichou (also known as Chabichou du Poitou) is a traditional semi-soft, unpasteurized, natural-rind French goat cheese (or Fromage de Chèvre) with a firm and creamy texture.[137][138] Chabichou is formed in a cylindrical shape which is called a "bonde", per the shape of the bunghole of a gun barrel.[137][139] and is aged for 10 to 20 days. It is the only goat cheese that is soft ripened allowed by Protected Designation of Origin regulations to be produced using pasteurized milk.[138] Chabichou is very white and smooth, and flexible to the palate, with a fine caprine odor. |  Chabichou2 |

| Champagne | France | Champagne (/ʃæmˈpeɪn/, French: [ʃɑ̃paɲ]) is a French sparkling wine. The term Champagne comes from its region where it is produced in "Champagne". It is illegal to label any product Champagne unless it came from the Champagne wine region of France and is produced under the rules of the appellation.[140] This alcoholic drink is produced from specific types of grapes grown in the Champagne region following rules that demand, among other things, specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within the Champagne region, specific grape-pressing methods and secondary fermentation of the wine in the bottle to cause carbonation.[141]  Vineyards in the Champagne region of France |

A glass of Champagne exhibiting the characteristic bubbles associated with the wine |

| Chaource cheese | Chaource | Chaource is a French cheese, originally manufactured in the village of Chaource in the Champagne-Ardenne region. Chaource is a cow's milk cheese, cylindrical in shape at around 10 cm in diameter and 6 cm in height, weighing either 250 or 450 g. The central pâte is soft, creamy in colour, and slightly crumbly, and is surrounded by a white Penicillium candidum rind. It was recognised as an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) cheese in 1970 and has been fully regulated since 1977. |  Chaource (fromage) 01 |

| Chevrotin | Savoy | Chevrotin is a soft goat's milk based cheese produced in the historical region of Savoy, (France). Since 2002 it has enjoyed an AOC designation.[142] | |

| Comté cheese | Franche-Comté | Comté (or Gruyère de Comté) (French pronunciation: [kɔ̃.te]) is a French cheese made from unpasteurized cow's milk in the Franche-Comté traditional province of eastern France bordering Switzerland and sharing much of its cuisine. Comté has the highest production of all French AOC cheeses, at around 66,500 tonnes annually.[143] It is classified as a Swiss-type or Alpine cheese. The cheese is made in discs, each between 40 cm (16 in) and 70 cm (28 in) in diameter, and around 10 cm (4 in) in height. Each disc weighs up to 50 kg (110 lb) with an FDM around 45%. The rind is usually a dusty-brown colour, and the internal paste, pâte , is a pale creamy yellow. The texture is relatively hard and flexible, and the taste is mild and slightly sweet. |

|

| Crottin de Chavignol | Loire Valley | Crottin de Chavignol is a goat cheese produced in the Loire Valley.[144] This cheese is the claim to fame for the village of Chavignol, France, which has only two hundred inhabitants. Protected by the AOC Seal,[145] Crottin de Chavignol is produced today with traditional methods. If a cheese is labelled "Crottin de Chavignol", it has to be from the area around Chavignol, and it has to meet the stringent AOC production criteria. |  Retail shop of one of Chavignol's two cheese makers |

| Époisses cheese | Époisses | Époisses, also known as Époisses de Bourgogne (French: [epwas də buʁɡɔɲ]), is a legally demarcated cheese made in the village of Époisses and its environs, in the département of Côte-d'Or, about halfway between Dijon and Auxerre, in the former duchy of Burgundy, France, from agricultural processes and resources traditionally found in that region. Époisses is a pungent soft-paste cows-milk cheese. Smear-ripened, "washed rind" (washed in brine and Marc de Bourgogne, the local pomace brandy), it is circular at around either 10 cm (3.9 in) or 18 cm (7.1 in) in diameter, with a distinctive soft red-orange color. It is made either from raw or pasteurized milk.[146] It is sold in a circular wooden box, and in restaurants, is sometimes served with a spoon due to its extremely soft texture. The cheese is often paired with Trappist beer or even Sauternes rather than a red wine.[citation needed] |  French cheese Époisses brand Germain in a box |

| Espelette pepper | northern territory | The Espelette pepper (French: Piment d'Espelette French pronunciation: [pi.mɑ̃ dɛs.pə.lɛt] ; Basque: Ezpeletako biperra) is a variety of Capsicum annuum that is cultivated in the French commune of Espelette, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, traditionally the northern territory of the Basque people.[147] On 1 June 2000, it was classified as an AOC product and was confirmed as an APO product on 22 August 2002. Chili pepper, originating in Central and South America, was introduced into France during the 16th century. After first being used medicinally, it became popular as a condiment and for the conservation of meats. It is now a cornerstone of Basque cuisine, where it has gradually replaced black pepper and it is a key ingredient in piperade.[148] AOC espelette peppers are cultivated in the following communes: Ainhoa, Cambo-les-Bains, Espelette, Halsou, Itxassou, Jatxou, Larressore, Saint-Pée-sur-Nivelle, Souraïde, and Ustaritz. They are harvested in late summer and, in September, characteristic festoons of pepper are hung on balconies and house walls throughout the communes to dry out.[148] An annual pepper festival organized by Confrérie du Piment d'Espelette, held since 1968 on the last weekend in October, attracts some 20,000 tourists.[149][150] This pepper attains a maximum grade of only 4,000 on the Scoville scale and is therefore considered only mildly hot. It can be purchased as festoons of fresh or dried peppers, as ground pepper, or puréed or pickled in jars.[148] In the United States, non-AOC espelette peppers grown and marketed in California may be fresher than imported AOC espelette peppers.[151] According to the Syndicat du Piment d’Espelette, the cooperative formed to get the AOC designation, there are 160 producers of AOC Piment d'Espelette that plant 183 hectares (450 acres) and in 2014, they produced 203 tons of powdered Piment d'Espelette and 1,300 tons of raw pepper.[152][153] |  Espelette pepper |

| Fourme de Montbrison | Montbrison | Fourme de Montbrison is a cow's-milk cheese[154] made in the regions of Rhône-Alpes and Auvergne in southern France. It derives its name from the town of Montbrison in the Loire department. The word fourme is derived from the Latin word forma meaning "shape", the same root from which the French word fromage is believed to have been derived.[155] The cheese is manufactured in tall cylindrical blocks weighing between 1.5 and 2 kg (3.3 and 4.4 lb). The blocks are 13 centimetres in diameter and 19 centimetres tall, although the cheese is most frequently sold in shops in much shorter cylindrical slices. Fourme de Montbrison has a characteristic orange-brown rind[156] with a creamy-coloured pâte, speckled with gentle streaks of blue mould. Its Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée status was granted in 1972 under a joint decree with Fourme d'Ambert, a similar blue cheese also from the same region. In 2002 the two cheeses received AOC status in their own right, recognizing the differences in their manufacture.[157] With a musty scent, the cheese is extremely mild for a blue cheese and has a dry taste. |

|

| Laguiole cheese | Aveyron | Laguiole (French pronunciation: [laɡjɔl], locally French pronunciation: [lajɔl]), sometimes called Tome de Laguiole, is a French cheese from the plateau of Aubrac, situated at between 800 - 1500m, in the region of Aveyron in the southern part of France. It takes its name from the little village Laguiole and has been protected under the French Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) since 1961 and by the amended decree in 1986. Laguiole is said to have been invented at a monastery in the mountains of Aubrac in the 19th century. According to historical accounts, the monks passed down the recipe for making this cheese from cattle during the alpages to the local buronniers, the owners of burons, or mountain huts. |  Laguiole (cheese) |

| Langres cheese | Langres | Langres is a French cheese from the plateau of Langres in the region of Champagne-Ardenne.[158] It has benefited from an Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) since 1991. Langres is a cow's milk cheese,[159] cylindrical in shape, weighing about 180 g. The central pâte is soft, creamy in colour, and slightly crumbly, and is surrounded by a white Penicillium candidum rind. It is a less pungent cheese than Époisses, its local competition. It is best eaten between May and August after 5 weeks of aging, but it is also excellent March through December. Production in 1998 was around 305 tons, a decline of 1.61% since 1996, and 2% on farms. |  Langres fromage AOP coupe |

| Lautrec Pink Garlic | Lautrec | Lautrec Pink Garlic[160] is a protected geographical indication

indicating a specific production of garlic from the Lautrec commune in the Tarn department in southern France. This crop has been, since 1966, listed under the French Label Rouge "ail rose" (pink garlic)[161] and under the protected geographical indication ail rose de Lautrec (Lautrec Pink Garlic) since June 12, 1996.[162] |

Manouille of the garlic. |

| Le Puy green lentil | Le Puy | Le Puy green lentil is a small, mottled, slate-gray/green lentil of the Lens esculenta puyensis (or L. culinaris puyensis) variety. In the US, this type of lentil may be grown and sold as French green lentils or Puy lentils. The term "Le Puy green lentil" is protected throughout the European Union (EU) under that governing body's Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), and in France as an appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC). In the EU, the term may only be used to designate lentils that come from the prefecture of Le Puy (most notably in the commune of Le Puy-en-Velay) in the Auvergne region of France.[163][164] These lentils have been grown in the region for over 2,000 years and it is said that they have gastronomic qualities that come from the terroir (in this case attributed to the area's volcanic soil). They are praised for their unique peppery flavor and the ability to retain their shape after cooking.[165][164] |  Puy lentils in a wooden bowl |

| Livarot cheese | Livarot | Livarot is a French cheese of the Normandy region,[166] originating in the commune of Livarot, and protected by an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC)[167] since 1975. It is a soft, pungent, washed rind cheese made from Normande cow's milk. The normal weight for a round of Livarot is 450 g, though it also comes in other weights. It is sold in cylindrical form with the orangish rind wrapped in 3 to 5 rings of dried reedmace (Typha latifolia). For this reason, it has been referred to as 'colonel', as the rings of dried bullrush resemble the stripes on a colonel's uniform. Sometimes green paper is also used. Its orange colour comes from different sources depending on the manufacturer, but is often annatto. The bacterium Brevibacterium linens is employed in fermentation. Production in 1998 was 1,101 tons, down 12.2% since 1996. Only 12% of Livarot are made from raw, unpasteurised milk. Its period of optimal tasting is spread out from May to September after a refining from 6 to 8 weeks, but it is also excellent from March to December. |  Livarot (fromage) 02 |

| Maroilles cheese | Picardy | Maroilles (pronounced mar wahl, also known as Marolles) is a cow's-milk cheese made in the regions of Picardy and Nord-Pas-de-Calais in northern France. It derives its name from the village of Maroilles in the region in which it is still manufactured. The cheese is sold in individual rectangular blocks with a moist orange-red washed rind and a strong smell. In its mass-produced form it is around 13 centimetres (5 in) square and 6 centimetres (2 in) in height, weighing around 700 grams (25 oz) In addition, according to its AOC regulations, cheeses eligible for AOC status can be one of three other sizes:

|

WikiCheese - Maroilles - 20150619 - 001 |

| Miel d'Alsace | Alsace | Miel d'Alsace is a honey from France that is protected under EU law with PGI status, first published under relevant laws in 2005.[168] The PGI status covers several varieties of honey produced in Alsace, namely silver fir honey, chestnut honey, acacia honey, lime honey, forest honey, and multi-flower honey.[169] According to official regulations, "Each type of honey develops its own physico-chemical and organoleptic characteristics, which are defined in the specification and correspond to the floral diversity of the region. The diversity of Alsatian honeys stems directly from the diversity of the prevailing ecosystems. Alsace comprises several areas: an area of mountains covered with softwoods, an area made up of hills and plateaux with vines, meadows and beech and chestnut forests, and a plain consisting of cropped land and meadows. The resulting diversity of ecosystems hence allows harvesting to take place from early spring to early autumn, providing a wide variety of products."[168] |  Etiquette Miel d’Alsace IGP |

| Morbier cheese | Morbier | Morbier is a semi-soft cows' milk cheese of France named after the small village of Morbier in Franche-Comté.[170] It is ivory colored, soft and slightly elastic, and is immediately recognizable by the distinctive thin black layer separating it horizontally in the middle.[170] It has a yellowish, sticky rind.[171]

The aroma of Morbier cheese is mild, with a rich and creamy flavour.[172] It has a semblance to Raclette cheese in consistency and aroma.[citation needed] The Jura and Doubs versions both benefit from an appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC), though other non-AOC Morbier exist on the market.[citation needed] |

|

| Morteau sausage | Morteau | The Morteau sausage (French: saucisse de Morteau; also known as the Belle de Morteau) is a traditional smoked sausage[173] from the Franche-Comté French historical region and take its name from the city of Morteau[174] in the Doubs department. It is smoked in traditional pyramidal chimneys, called "tuyés".[173] It is a strongly flavoured and very dense uncooked sausage. It is produced on the plateau and in the mountains of the Jura mountains in the Doubs at an altitude greater than 600 m (2,000 ft).[173] The city of Morteau is at the centre of this artisanal industry. Morteau sausage is produced using only pork from the Franche-Comté region, because in this mountainous region the animals are fattened traditionally. In addition, to be permitted to use the label "Saucisse de Morteau", the sausages must be smoked for at least 48 hours with sawdust from conifer and juniper within the tuyé. It is not cooked, however, as the combustion is accompanied by a strong current of air. The Morteau sausage is protected by the European Union's PGI[175] label, which guarantees its quality, origin and method of preparation as a regional French specialty. Authentic Morteau typically comes with a metal tag as well as a small wooden stick wrapped around the end of the link. |  Morteau sausage |

| Munster cheese | Vosges | Munster (French pronunciation: [mœ̃stɛʁ]), Munster-géromé, or (Alsatian) Minschterkaas, is a strong-smelling soft cheese with a subtle taste, made mainly from milk first produced in the Vosges, between Alsace-Lorraine and Franche-Comté regions in France.[176] The name "Munster" is derived from the Alsace town of Munster, where, among Vosgian abbeys and monasteries, the cheese was conserved and matured in monks' cellars. |  Munster |

| Neufchâtel cheese | Neufchâtel-en-Bray | Neufchâtel (French: [nøʃɑtɛl] ( |

Cœur de Neufchâtel 08 |

| Olive de Nice | Nice | The Olive de Nice is a PDO olive from the Alpes-Maritimes area of France. The rules state that they must be of the Cailletier variety, and harvest must not exceed 6 tons per hectare. |  Filet Olive de Nice |

| Ossau-Iraty | Basque | Ossau-Iraty is an Occitan-Basque cheese made from sheep milk. It has been recognized as an appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) product since 1980. It is one of three sheep's milk cheeses granted AOC status in France (the others are Roquefort and Brocciu). It is of ancient origin, traditionally made by the shepherds in the region.[179] |  Ossau-Iraty |

| Pélardon | Cévennes | Pélardon, formerly called paraldon, pélardou and also péraudou, is a French cheese from the Cévennes range of the Languedoc-Roussillon region.[180] It is a traditional cheese made from goat's milk.[180] It is round soft-ripened cheese covered in a white mold (à pâte molle à croûte fleurie) weighing approximately 60 grams, with a diameter of 60–70 mm and a height of 22–27 mm.[180] Pélardon has benefited from Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) status since August 2000. |  Pelardon |

| Picodon | Rhône | Picodon is a goats-milk cheese made in the region around the Rhône in southern France. The name means "spicy" in Occitan.[181] The cheese itself comes in a number of varieties, each small, flat and circular in shape varying from speckled white to golden in colour. Between 5 and 8 cm (2.0 and 3.1 in) in diameter and between 1.8 and 2.5 cm (0.71 and 0.98 in) in height, they range from around 40 to 100 grams. The pâte of the cheese is spicy and unusually dry, whilst retaining a smooth, fine texture. Whilst young the cheese has a soft white rind and has a gentle, fresh taste. If aged for longer, the cheese can lose half of its weight resulting in a golden rind with a much harder centre and a more concentrated flavour. |  Wikicheese - Picodon - 20150417 - 003 |

| Pont-l'Évêque cheese | Pont-l'Évêque | Pont-l'Évêque is a French cheese, originally manufactured in the area around the commune of Pont-l'Évêque, between Deauville and Lisieux in the Calvados département of Normandy. It is probably the oldest Norman cheese still in production.[182] Pont-l'Évêque was recognised as an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) cheese on August 30, 1972, reaching full status in 1976. Its production was defined and protected with a decree of December 29, 1986.[183] Le Petit Futé guides commend that the best AOC Pont-l'évêque comes from the Pays d'Auge, which includes the Canton of Pont-l'Evêque itself.[184][185] |  Pont-l'Évêque 02 |

| Pouligny-Saint-Pierre cheese | Indre | Pouligny-Saint-Pierre is a French goats'-milk cheese made in the Indre department of central France. Its name is derived from the commune of Pouligny-Saint-Pierre in the Indre department where it was first made in the 18th century. The cheese is distinctive, being pyramidal in shape and golden brown in colour with speckles of grey-blue mould, and is often known by the nicknames "Eiffel Tower" or "Pyramid". It has a square base 6.5 cm wide, is around 9 cm high, and weighs 250 grams (8.8 oz).[186] The central pâte is bright white with a smooth, crumbly texture that mixes an initial sour taste with salty and sweet overtones. The exterior has a musty odour reminiscent of hay. It is made exclusively from unpasteurised milk. Both fermier (farmhouse) and industriel (dairy) production is used with the fermier bearing a green label, and industriel a red label. Its region of production is relatively small, taking in only 22 communes. |  Pouligny-saint-pierre (fromage) 03 |

| Reblochon | Savoie | Reblochon (French pronunciation: [ʁə.blɔ.ʃɔ̃]) is a soft washed-rind and smear-ripened[187] French cheese made in the Alpine region of Savoie from raw cow's milk. It has its own AOC designation. Reblochon was first produced in the Thônes and Arly valleys, in the Aravis massif. Thônes remains the centre of Reblochon production; the cheeses are still made in the local cooperatives. Until 1964 Reblochon was also produced in Italian areas of the Alps. Subsequently, the Italian cheese has been sold in declining quantities under such names as Rebruchon and Reblò alpino. |  Farmhouse Reblochon, drying before ripening |

| Rocamadour cheese | Rocamadour | Rocamadour is a French cheese from the southwest part of the country. It is produced in the regions of Périgord and Quercy and takes its name from the village of Rocamadour in the département of the Lot. Rocamadour belongs to a family of goat cheeses called Cabécous and has benefited from being accorded an AOC (appellation d'origine contrôlée) designation since 1996. It is a very small whitish cheese (average weight 35 g) with a flat round shape (see illustration). Rocamadour is usually sold very young after just 12–15 days of aging and is customarily consumed on hot toast or in salads. Rocamadour can be aged further. After several months it takes on a more intense flavor and is typically eaten on its own with a red wine toward the end of the meal. Production: 546 tonnes in 1998 (+24.1% since 1996), 100% with raw, unpasteurized goat milk (50% on farms). |  Rocamadour AOC |

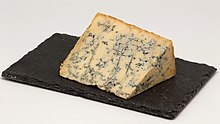

| Roquefort | Roquefort-sur-Soulzon | Roquefort is a sheep milk cheese from Southern France, and is one of the world's best known blue cheeses.[5] Though similar cheeses are produced elsewhere, EU law dictates that only those cheeses aged in the natural Combalou caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon may bear the name Roquefort, as it is a recognised geographical indication, or has a protected designation of origin. The cheese is white, tangy, crumbly and slightly moist, with distinctive veins of blue mold. It has a characteristic fragrance and flavor with a notable taste of butyric acid; the blue veins provide a sharp tang. It has no rind; the exterior is edible and slightly salty. A typical wheel of Roquefort weighs between 2.5 and 3 kg (5.5 and 6.6 lb), and is about 10 cm (4 in) thick. Each kilogram of finished cheese requires about 4.5 litres (1.2 US gal) of milk to produce. In France, Roquefort is often called the "King of Cheeses" or the "Cheese of Kings", although those names are also used for other cheeses.[188] In 1925, the cheese was the recipient of France's first Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée when regulations controlling its production and naming were first defined.[189] In 1961, in a landmark ruling that removed imitation, the Tribunal de Grande Instance at Millau decreed that, although the method for the manufacture of the cheese could be followed across the south of France, only those cheeses whose ripening occurred in the natural caves of Mont Combalou in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon were permitted to bear the name Roquefort.[2] |  Wikicheese - Roquefort - 20150417 - 003 |

| Saint-Nectaire | Auvergne | Saint-Nectaire is a French cheese made in the Auvergne region of central France. The cheese has been made in Auvergne since at least the 17th century.Saint-Nectaire is an Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC), a certification given to French agricultural products based on a set of clearly defined standards. For example, it must be made of cow's milk in a specifically delimited area in the Monts-Dore region. The Appellation was first recognized at a national level and awarded AOC status in 1955.[190] At that time, the Saint-Nectaire cheese was only produced on farms from milk from their own cows. When the appellation was accorded, industrial milk and dairy factories were also allowed to produce Saint-Nectaire. To differentiate between products made from the two processes, farmstead cheeses are marked with a small oval label in green casein, while a square label is applied to industrial cheeses. In 1996, a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) was given to Saint-Nectaire, extending name protection to the entire European Union. A new appellation, "petit-Saint-Nectaire" (meaning "small Saint-Nectaire"), given to cheeses that weigh 600 grams, was later included in the specifications. |  Box of saint Nectaire before aging (affinage) |

| Selles-sur-Cher cheese | Centre-Val de Loire | Selles-sur-Cher is a French goat-milk cheese made in Centre-Val de Loire, France. Its name is derived from the commune of Selles-sur-Cher, Loir-et-Cher, where it was first made in the 19th century. The cheese is sold in small cylindrical units, around 8 cm in diameter at the base (reduced to around 7 cm at the top) and 2–3 cm in height, and weighing around 150 g.[191] The central pâte is typical of goat cheese, rigid and heavy at first but moist and softening as it melts in the mouth. Its taste is lightly salty with a persistent aftertaste. The exterior is dry with a grey-blue mould covering its surface, and has a musty odour. The mould is often eaten and has a considerably stronger flavour. Around 1.3 l (0.34 US gal) of unpasteurised milk are used to make a single 150 grams (5.3 oz) cheese. After the milk is soured using the ferment it is heated to around 20 °C (68 °F). A small amount of rennet is added and left for 24 hours. Unlike most other types of cheese, the curd is ladled directly into its mould which contains tiny holes for the whey to run off naturally. The cheese is then left in a cool ventilated room at 80% humidity (dry compared to a typical cellar at 90–100% humidity) for between 10 and 30 days, during which time it dries as the mould forms on its exterior. An initial coating of charcoal encourages the formation of its characteristic mould. Selles-sur-Cher is made in fermier (36%), coopérative, and industriel production, with 747 tons produced in 2005.[192] Although industriel production is now all year round, it is at its best between spring and autumn. The cheese was awarded AOC status in 1975.[193] According to its AOC regulations, the cheese must be made within certain regions of the departments of Cher, Indre and Loir-et-Cher. |  Selles-sur-cher 1 |

| Valençay cheese | Berry | Valençay is a cheese made in the province of Berry in central France. Its name is derived from the town of Valençay in the Indre department. Distinctive in its truncated pyramidal shape, Valençay is an unpasteurised goats-milk cheese weighing 200–250 grams (7.1–8.8 oz) and around 7 cm (2.8 in) in height. Its rustic blue-grey colour is made by the natural moulds that form its rind, darkened with a dusting of charcoal. The young cheese has a fresh, citric taste, with age giving it a nutty taste characteristic of goats cheeses. The cheese achieved AOC status in 1998 making Valençay the first region to achieve AOC status for both its cheese and its wine.[194] |  Valençay 04 |

Germany[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aachener Printen | Aachen | Aachener Printen are a type of Lebkuchen originating from the city of Aachen in Germany. Somewhat similar to gingerbread, they were originally sweetened with honey, but are now generally sweetened with a syrup made from sugar beets. The term is a protected designation of origin and so all manufacturers can be found in or near Aachen. The first pastries of this kind most likely originated from the city of Dinant in nearby Belgium. The city has produced pastries with engraved pictures (couques de Dinant) for over a thousand years.[195] Copper producing (another specialty of Dinant) craftsmen who emigrated to Aachen in the 15th century probably brought the recipe, concept and tradition of engraved pastries with them to Aachen. Originally, the Printen were sold by Aachen's pharmacists since some of their ingredients (honey, several herbs and spices) were considered to possess medical benefits. |  Aachener Printen 0293 |

| Black Forest ham | Black Forest | Black Forest ham (German: Schwarzwälder Schinken) is a variety of dry-cured smoked ham produced in the Black Forest region of Germany. In 1959, Hans Adler from Bonndorf pioneered manufacturing and selling Original Black Forest ham by retail and mail order.[196] Since 1997, the term Black Forest ham has been a Protected Geographical Indication in the European Union,[197] which means that any product sold in the EU as Black Forest ham must be traditionally and at least partially manufactured (prepared, processed or produced) within the Black Forest region in Germany. However, this designation is not recognized outside the EU, particularly in Canada and the United States, where commercially produced hams of various types and quality are marketed and sold as Black Forest ham. |  Jambon fumé de Forêt Noire |

| Handkäse | Germany | Handkäse (pronounced [ˈhantkɛːzə]; literally: "hand cheese") is a German regional sour milk cheese (similar to Harzer) and is a culinary speciality of Frankfurt am Main, Offenbach am Main, Darmstadt, Langen, and other parts of southern Hesse. It gets its name from the traditional way of producing it: forming it with one's own hands.[198] It is a small, translucent, yellow cheese with a pungent aroma that some people may find unpleasant. It is sometimes square, but more often round in shape. Often served as an appetizer or as a snack with Apfelwein (Ebbelwoi or cider), it is traditionally topped with chopped onions,[199] locally known as "Handkäse mit Musik" (literally: hand cheese with music). It is usually eaten with caraway on it, but since many people in Germany do not like this spice, in many areas it is served on the side. Some Hessians say that it is a sign of the quality of the establishment when caraway is in a separate dispenser. As a sign of this, many restaurants have, in addition to the salt and pepper, a little pot for caraway seeds. Strangers to this custom probably ask where the Musik is. They most likely are told, Die Musik kommt später, i.e. the music "comes later". This is a euphemism for the flatulence that the raw onions usually provide. A more polite, but less likely explanation for the Musik is that the flasks of vinegar and oil customarily provided with the cheese would strike a musical note when they hit each other. Handkäse is popular among dieters and some health food devotees. It is also popular among bodybuilders, runners, and weightlifters for its high content of protein while being relatively low in fat. |  Handkäs mit Musik (Hessian: Handkäse with music); marinated Handkäse |

| Kölsch (beer) | Cologne | Kölsch (German pronunciation: [kœlʃ]) is a style of beer originating in Cologne, Germany. It has an original gravity between 11 and 14 degrees Plato (specific gravity of 1.044 to 1.056). In appearance, it is bright and clear with a straw-yellow hue. Since 1997, the term "Kölsch" has had a protected geographical indication (PGI) within the European Union, indicating a beer that is made within 50 kilometres (30 mi) of the city of Cologne and brewed according to the Kölsch Konvention as defined by the members of the Cologne Brewery Association (Kölner Brauerei-Verband). Kölsch is one of the most strictly defined beer styles in Germany: according to the Konvention, it is a pale, highly attenuated, hoppy, bright (i.e. filtered and not cloudy) top-fermenting beer, and must be brewed according to the Reinheitsgebot.[200] Kölsch is warm fermented with top-fermenting yeast, then conditioned at cold temperatures like a lager.[201] This brewing process is similar to that used for Düsseldorf's altbier. |  Zunft-Kölsch Glas |

| Lübeck Marzipan | Lübeck | Lübeck Marzipan (German: Lübecker Marzipan) refers to marzipan originating from the city of Lübeck in northern Germany and has been protected by an EU Council Directive as a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) since 1996.[202] The quality requirements of Lübeck Marzipan are set higher than those of conventional marzipan[203] and are regulated by the RAL German Institute for Quality Assurance and Classification. For a product to qualify as Lübeck Marzipan, a product must contain no more than 30% sugar, while the Lübeck Fine Marzipan must contain up to 10% sugar.[204] |  A selection of different marzipan products produced by Niederegger |

| Maultasche | Swabia | Maultaschen (singular Maultasche ( |

Maultaschen |

| Münchener Bier | Germany | Münchener Bier is a beer from Germany that is protected under EU law with PGI status, first published under relevant laws in 1998. This designation was one of six German beers registered with the PGI designation at the time.[207] |  Typical beers of the PGI, from Hofbräu München. |

| Nürnberger Bratwürste | Nuremberg | The small, thin bratwurst from Franconia's largest city, Nuremberg, was first documented in 1567; it is 7 to 9 cm (2.8 to 3.5 in) long, and weighs between 20 and 25 g. The denominations Nürnberger Bratwurst and Nürnberger Rostbratwurst (Rost comes from the grill above the cooking fire) are Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) under EU law since 2003,[208] and may therefore only be produced in the city of Nürnberg, where an "Association for the Protection of Nürnberger Bratwürste" was established in 1997.[209] Pork-based and typically seasoned with fresh marjoram which gives them their distinctive flavour, these sausages are traditionally grilled over a beechwood fire. As a main dish three to six pairs are served on a pewter plate with either sauerkraut or potato salad, and accompanied by a dollop of horseradish or mustard. They are also sold as a snack by street vendors as Drei im Weckla (three in a bun; the spelling Drei im Weggla is also common, Weggla/Weckla being the word for "bread roll" in the Nuremberg dialect), with mustard. Another way of cooking Nuremberg sausages is in a spiced vinegar and onion stock; this is called Blaue Zipfel (blue lobes). |  Nürnberger Bratwurst with sauerkraut and mustard, as served in the Nürnberger Bratwurst Glöckl in Munich |

| Nürnberger Lebkuchen | Nuremberg | Lebkuchen (German pronunciation: [ˈleːpˌku:xn] ( |

Lebkuchenscan |

| Obatzda | Bavaria | Obatzda German pronunciation: [ˈoːbatsdɐ] (also spelt Obazda and Obatzter)[citation needed] is a Bavarian cheese delicacy. It is prepared by mixing two thirds aged soft cheese, usually Camembert ( or similar cheeses may be used as well) and one third butter. Sweet or hot paprika powder, salt and pepper are the traditional seasonings, as well as a small amount of beer.[215] An optional amount of onions, garlic, horseradish, cloves and ground or roasted caraway seeds may be used and some cream or cream cheese as well.[215] The cheeses and spices are mixed together into a more or less smooth mass according to taste. It is usually eaten spread on bread or pretzels. Obatzda is a classic example of Bavarian biergarten food.[216] A similar Austrian/Hungarian/Slovak recipe is called Liptauer which uses fresh curd cheese as a substitute for the soft cheeses and the butter, but uses about the same spice mix.[217] In 2015, within the EU, obatzda was granted PGI certification.[218] |  Obatzda in a Paulaner pub |

| Rheinischer Zuckerrübensirup | Germany | Rheinischer Zuckerrübensirup is a PGI protected sugar-beet syrup.[219] | |

| Spreewald gherkins | Brandenburg | Spreewald gherkins (German: Spreewälder Gurken or Spreewaldgurken) are a specialty pickled cucumber from Brandenburg, which are protected by the EU as a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). In the 1870s, Theodor Fontane found that the Spreewaldgurke stood at the top of the agricultural products in Brandenburg's Spreewald:

|

Spreewaldgurke2 |

| Thuringian sausage | Thuringia | Thuringian sausage, or Thüringer Bratwurst in German is a unique sausage from the German state of Thuringia which has protected geographical indication status under European Union law. In 2006, the Deutsches Bratwurstmuseum, opened in Holzhausen, part of the Wachsenburggemeinde near Arnstadt, the first museum devoted exclusively to the Thuringian sausage.[221] Prior to Thuringian sausages acquiring PGI status in the EU, a type of Luxembourgish sausage was locally known as a Thüringer. It is now referred to as "Lëtzebuerger Grillwurscht" (Luxembourgish: grill sausage). |  Thuringian sausages in Berlin |

Greece[]

| Product name | Area | Short description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chios Mastiha | Chios | Chios Mastiha Liqueur (Greek: Μαστίχα Χίου, Greek pronunciation: [masˈtixa ˈçi.u]) is a liqueur flavoured with mastic distillate or mastic oil from the island of Chios. The name Chios Mastiha has protected designation of origin status in the European Union.[222] Chios Mastiha liqueur is clear with a sweet aroma. It is traditionally served cold. |  Mastic shrub — Pistacia lentiscus |

| Feta | Greece | Feta (Greek: φέτα, féta) is a Greek brined curd white cheese made from sheep's milk or from a mixture of sheep and goat's milk. It is a soft, brined white cheese with small or no holes, a compact touch, few cuts, and no skin. It is formed into large blocks, and aged in brine. Its flavor is tangy and salty, ranging from mild to sharp. It is crumbly and has a slightly grainy texture. Feta is used as a table cheese, in salads such as Greek salad, and in pastries, notably the phyllo-based Greek dishes spanakopita ("spinach pie") and tyropita ("cheese pie"). It is often served with olive oil or olives, and sprinkled with aromatic herbs such as oregano. It can also be served cooked (often grilled), as part of a sandwich, in omelettes, and many other dishes. Since 2002, feta has been a protected designation of origin in the European Union. EU legislation limits the name feta to cheeses produced in the traditional way in particular areas of Greece, which are made from sheep's milk, or from a mixture of sheep's and up to 30% of goat's milk from the same area.[223] Similar white, brined cheeses (often called "white cheese" in various languages) are made traditionally in the Mediterranean and around the Black Sea, and more recently elsewhere. Outside the EU, the name feta is often used generically for these cheeses.[224] |  Feta Cheese |