Schulze method

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

The Schulze method (/ˈʃʊltsə/) is an electoral system developed in 1997 by Markus Schulze that selects a single winner using votes that express preferences. The method can also be used to create a sorted list of winners. The Schulze method is also known as Schwartz Sequential dropping (SSD), cloneproof Schwartz sequential dropping (CSSD), the beatpath method, beatpath winner, path voting, and path winner.

The Schulze method is a Condorcet method, which means that if there is a candidate who is preferred by a majority over every other candidate in pairwise comparisons, then this candidate will be the winner when the Schulze method is applied.

The output of the Schulze method (defined below) gives an ordering of candidates. Therefore, if several positions are available, the method can be used for this purpose without modification, by letting the k top-ranked candidates win the k available seats. Furthermore, for proportional representation elections, a single transferable vote variant has been proposed.

The Schulze method is used by several organizations including Wikimedia, Debian, Ubuntu, Gentoo, Pirate Party political parties and many others.

Description of the method[]

Ballot[]

The input for the Schulze method is the same as for other ranked single-winner electoral systems: each voter must furnish an ordered preference list on candidates where ties are allowed (a strict weak order).[1]

One typical way for voters to specify their preferences on a ballot is as follows. Each ballot lists all the candidates, and each voter ranks this list in order of preference using numbers: the voter places a '1' beside the most preferred candidate(s), a '2' beside the second-most preferred, and so forth. Each voter may optionally:

- give the same preference to more than one candidate. This indicates that this voter is indifferent between these candidates.

- use non-consecutive numbers to express preferences. This has no impact on the result of the elections, since only the order in which the candidates are ranked by the voter matters, and not the absolute numbers of the preferences.

- keep candidates unranked. When a voter doesn't rank all candidates, then this is interpreted as if this voter (i) strictly prefers all ranked to all unranked candidates, and (ii) is indifferent among all unranked candidates.

Computation[]

Let be the number of voters who prefer candidate to candidate .

A path from candidate to candidate is a sequence of candidates with the following properties:

- and .

- For all .

In other words, in a pairwise comparison, each candidate in the path will beat the following candidate.

The strength of a path from candidate to candidate is the smallest number of voters in the sequence of comparisons:

- For all .

For a pair of candidates and that are connected by at least one path, the strength of the strongest path is the maximum strength of the path(s) connecting them. If there is no path from candidate to candidate at all, then .

Candidate is better than candidate if and only if .

Candidate is a potential winner if and only if for every other candidate .

It can be proven that and together imply .[1]: §4.1 Therefore, it is guaranteed (1) that the above definition of "better" really defines a transitive relation and (2) that there is always at least one candidate with for every other candidate .

Example[]

In the following example 45 voters rank 5 candidates.

The pairwise preferences have to be computed first. For example, when comparing A and B pairwise, there are 5+5+3+7=20 voters who prefer A to B, and 8+2+7+8=25 voters who prefer B to A. So and . The full set of pairwise preferences is:

| 20 | 26 | 30 | 22 | ||

| 25 | 16 | 33 | 18 | ||

| 19 | 29 | 17 | 24 | ||

| 15 | 12 | 28 | 14 | ||

| 23 | 27 | 21 | 31 |

The cells for d[X, Y] have a light green background if d[X, Y] > d[Y, X], otherwise the background is light red. There is no undisputed winner by only looking at the pairwise differences here.

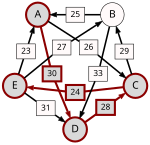

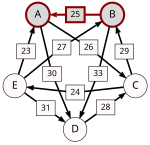

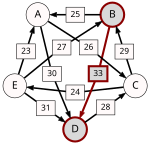

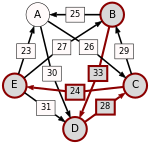

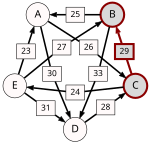

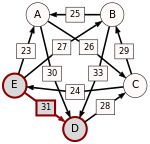

Now the strongest paths have to be identified. To help visualize the strongest paths, the set of pairwise preferences is depicted in the diagram on the right in the form of a directed graph. An arrow from the node representing a candidate X to the one representing a candidate Y is labelled with d[X, Y]. To avoid cluttering the diagram, an arrow has only been drawn from X to Y when d[X, Y] > d[Y, X] (i.e. the table cells with light green background), omitting the one in the opposite direction (the table cells with light red background).

One example of computing the strongest path strength is p[B, D] = 33: the strongest path from B to D is the direct path (B, D) which has strength 33. But when computing p[A, C], the strongest path from A to C is not the direct path (A, C) of strength 26, rather the strongest path is the indirect path (A, D, C) which has strength min(30, 28) = 28. The strength of a path is the strength of its weakest link.

For each pair of candidates X and Y, the following table shows the strongest path from candidate X to candidate Y in red, with the weakest link underlined.

To From

|

A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | N/A |  |

|

|

|

A |

| B |  |

N/A |  |

|

|

B |

| C |  |

|

N/A |  |

|

C |

| D |  |

|

|

N/A |  |

D |

| E |  |

|

|

|

N/A | E |

| A | B | C | D | E | From To

|

| 28 | 28 | 30 | 24 | ||

| 25 | 28 | 33 | 24 | ||

| 25 | 29 | 29 | 24 | ||

| 25 | 28 | 28 | 24 | ||

| 25 | 28 | 28 | 31 |

Now the output of the Schulze method can be determined. For example, when comparing A and B, since , for the Schulze method candidate A is better than candidate B. Another example is that , so candidate E is better than candidate D. Continuing in this way, the result is that the Schulze ranking is , and E wins. In other words, E wins since for every other candidate X.

Implementation[]

The only difficult step in implementing the Schulze method is computing the strongest path strengths. However, this is a well-known problem in graph theory sometimes called the widest path problem. One simple way to compute the strengths, therefore, is a variant of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm. The following pseudocode illustrates the algorithm.

# Input: d[i,j], the number of voters who prefer candidate i to candidate j.

# Output: p[i,j], the strength of the strongest path from candidate i to candidate j.

for i from 1 to C

for j from 1 to C

if i ≠ j then

if d[i,j] > d[j,i] then

p[i,j] := d[i,j]

else

p[i,j] := 0

for i from 1 to C

for j from 1 to C

if i ≠ j then

for k from 1 to C

if i ≠ k and j ≠ k then

p[j,k] := max (p[j,k], min (p[j,i], p[i,k]))

This algorithm is efficient and has running time O(C3) where C is the number of candidates.

Ties and alternative implementations[]

This article may require copy editing for you/your, contractions. (June 2021) |

When allowing users to have ties in their preferences, the outcome of the Schulze method naturally depends on how these ties are interpreted in defining d[*,*]. Two natural choices are that d[A, B] represents either the number of voters who strictly prefer A to B (A>B), or the margin of (voters with A>B) minus (voters with B>A). But no matter how the ds are defined, the Schulze ranking has no cycles, and assuming the ds are unique it has no ties.[1]

Although ties in the Schulze ranking are unlikely,[2][citation needed] they are possible. Schulze's original paper[1] proposed breaking ties in accordance with a voter selected at random, and iterating as needed.

An alternative way to describe the winner of the Schulze method is the following procedure:[citation needed]

- draw a complete directed graph with all candidates, and all possible edges between candidates

- iteratively [a] delete all candidates not in the Schwartz set (i.e. any candidate x which cannot reach all others who reach x) and [b] delete the graph edge with the smallest value (if by margins, smallest margin; if by votes, fewest votes).

- the winner is the last non-deleted candidate.

There is another alternative way to demonstrate the winner of the Schulze method. This method is equivalent to the others described here, but the presentation is optimized for the significance of steps being visually apparent as you go through it, not for computation.

- Make the results table, called the "matrix of pairwise preferences," such as used above in the example. If using margins rather than raw vote totals, subtract it from its transpose. Then every positive number is a pairwise win for the candidate on that row (and marked green), ties are zeroes, and losses are negative (marked red). Order the candidates by how long they last in elimination.

- If there's a candidate with no red on their line, they win.

- Otherwise, draw a square box around the Schwartz set in the upper left corner. You can describe it as the minimal "winner's circle" of candidates who do not lose to anyone outside the circle. Note that to the right of the box there is no red, which means it's a winner's circle, and note that within the box there is no reordering possible that would produce a smaller winner's circle.

- Cut away every part of the table that isn't in the box.

- If there is still no candidate with no red on their line, something needs to be compromised on; every candidate lost some race, and the loss we tolerate the best is the one where the loser obtained the most votes. So, take the red cell with the highest number (if going by margins, the least negative), make it green—or any color other than red—and go back step 2.

Here is a margins table made from the above example. Note the change of order used for demonstration purposes.

| E | A | C | B | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 1 | -3 | 9 | 17 | |

| A | -1 | 7 | -5 | 15 | |

| C | 3 | -7 | 13 | -11 | |

| B | -9 | 5 | -13 | 21 | |

| D | -17 | -15 | 11 | -21 |

The first drop (A's loss to E by 1 vote) doesn't help shrink the Schwartz set.

| E | A | C | B | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 1 | -3 | 9 | 17 | |

| A | -1 | 7 | -5 | 15 | |

| C | 3 | -7 | 13 | -11 | |

| B | -9 | 5 | -13 | 21 | |

| D | -17 | -15 | 11 | -21 |

So we get straight to the second drop (E's loss to C by 3 votes), and that shows us the winner, E, with its clear row.

| E | A | C | B | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 1 | -3 | 9 | 17 | |

| A | -1 | 7 | -5 | 15 | |

| C | 3 | -7 | 13 | -11 | |

| B | -9 | 5 | -13 | 21 | |

| D | -17 | -15 | 11 | -21 |

This method can also be used to calculate a result, if you make the table in such a way that you can conveniently and reliably rearrange the order of the candidates on both row and column (use the same order on both at all times).

Satisfied and failed criteria[]

Satisfied criteria[]

The Schulze method satisfies the following criteria:

- Unrestricted domain

- Non-imposition (a.k.a. citizen sovereignty)

- Non-dictatorship

- Pareto criterion[1]: §4.3

- Monotonicity criterion[1]: §4.5

- Majority criterion

- Majority loser criterion

- Condorcet criterion

- Condorcet loser criterion

- Schwartz criterion

- Smith criterion[1]: §4.7

- Independence of Smith-dominated alternatives[1]: §4.7

- Mutual majority criterion

- Independence of clones[1]: §4.6

- Reversal symmetry[1]: §4.4

- Mono-append[3]

- Mono-add-plump[3]

- Resolvability criterion[1]: §4.2

- Polynomial runtime[1]: §2.3"

- prudence[1]: §4.9"

- MinMax sets[1]: §4.8"

- Woodall's plurality criterion if winning votes are used for d[X,Y]

- Symmetric-completion[3] if margins are used for d[X,Y]

Failed criteria[]

Since the Schulze method satisfies the Condorcet criterion, it automatically fails the following criteria:

- Participation[1]: §3.4

- Consistency

- Invulnerability to compromising

- Invulnerability to burying

- Later-no-harm

Likewise, since the Schulze method is not a dictatorship and agrees with unanimous votes, Arrow's Theorem implies it fails the criterion

The Schulze method also fails

- Peyton Young's criterion Local Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives.

Comparison table[]

The following table compares the Schulze method with other preferential single-winner election methods:

| System | Monotonic | Condorcet | Majority | Condorcet loser | Majority loser | Mutual majority | Smith | ISDA | LIIA | Independence of clones | Reversal symmetry | Participation, consistency | Later-no‑harm | Later-no‑help | Polynomial time | Resolvability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schulze | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ranked pairs | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Tideman's Alternative | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kemeny–Young | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Copeland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Nanson | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Black | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Instant-runoff voting | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smith/IRV | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Borda | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Baldwin | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bucklin | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Plurality | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Contingent voting | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coombs[4] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| MiniMax | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-plurality[4] | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Sri Lankan contingent voting | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Supplementary voting | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dodgson[4] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

The main difference between the Schulze method and the ranked pairs method can be seen in this example:

Suppose the MinMax score of a set X of candidates is the strength of the strongest pairwise win of a candidate A ��� X against a candidate B ∈ X. Then the Schulze method, but not Ranked Pairs, guarantees that the winner is always a candidate of the set with minimum MinMax score.[1]: §4.8 So, in some sense, the Schulze method minimizes the largest majority that has to be reversed when determining the winner.

On the other hand, Ranked Pairs minimizes the largest majority that has to be reversed to determine the order of finish, in the minlexmax sense.[citation needed][5] In other words, when Ranked Pairs and the Schulze method produce different orders of finish, for the majorities on which the two orders of finish disagree, the Schulze order reverses a larger majority than the Ranked Pairs order.

History[]

The Schulze method was developed by Markus Schulze in 1997. It was first discussed in public mailing lists in 1997–1998[6] and in 2000.[7] Subsequently, Schulze method users included Debian (2003),[8] Gentoo (2005),[9] Topcoder (2005),[10] Wikimedia (2008),[11] KDE (2008),[12] the Pirate Party of Sweden (2009),[13] and the Pirate Party of Germany (2010).[14] In the French Wikipedia, the Schulze method was one of two multi-candidate methods approved by a majority in 2005,[15] and it has been used several times.[16] The newly formed Boise, Idaho chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America in February chose this method for their first special election held in March 2018.[17]

In 2011, Schulze published the method in the academic journal Social Choice and Welfare.[1]

Users[]

The Schulze method is used by the city of Silla for all referendums. It is used by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, by the Association for Computing Machinery, and by USENIX through their use of the HotCRP decision tool. The Schulze method is used by the cities of Turin and San Donà di Piave and by the London Borough of Southwark through their use of the WeGovNow platform, which in turn uses the LiquidFeedback decision tool. Organizations which currently use the Schulze method include:

- AEGEE - European Students' Forum[18]

- Annodex Association[19]

- Associated Student Government at Northwestern University[20]

- Associated Student Government at University of Freiburg[21]

- Associated Student Government at the Computer Sciences Department of the University of Kaiserslautern[22]

- Berufsverband der Kinder- und Jugendärzte (BVKJ)[23]

- BoardGameGeek[24]

- Club der Ehemaligen der Deutschen SchülerAkademien e. V. [25]

- Collective Agency[26]

- County Highpointers[27]

- Debian[8]

- EuroBillTracker[28]

- European Democratic Education Community (EUDEC)[29]

- FFmpeg[30]

- Five Star Movement of Campobasso,[31] Fondi,[32] Monte Compatri,[33] Montemurlo,[34] Pescara,[35] and San Cesareo[36]

- Flemish Society of Engineering Students Leuven[37]

- Free Geek[38]

- Free Hardware Foundation of Italy[39]

- Gentoo Foundation[9]

- GlitzerKollektiv [40]

- GNU Privacy Guard (GnuPG)[41]

- Graduate Student Organization at the State University of New York: Computer Science (GSOCS)[42]

- Haskell[43]

- Hillegass Parker House[44]

- Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)[45]

- Ithaca Generator[46]

- Kanawha Valley Scrabble Club[47]

- KDE e.V.[12]

- Kingman Hall[48]

- Knight Foundation[49]

- Kubuntu[50]

- Kumoricon[51]

- League of Professional System Administrators (LOPSA)[52]

- LiquidFeedback[53]

- Madisonium[54]

- Metalab[55]

- Music Television (MTV)[56]

- Neo[57]

- New Liberals[58]

- Noisebridge[59]

- OpenEmbedded[60]

- OpenStack[61]

- OpenSwitch[62]

- Pirate Party Australia[63]

- Pirate Party of Austria[64]

- Pirate Party of Belgium[65]

- Pirate Party of Brazil

- Pirate Party of Germany[14]

- Pirate Party of Iceland[66]

- Pirate Party of Italy[67]

- Pirate Party of the Netherlands[68]

- Pirate Party of New Zealand[69]

- Pirate Party of Sweden[13]

- Pirate Party of Switzerland[70]

- Pirate Party of the United States[71]

- RLLMUK[72]

- Squeak[73]

- Students for Free Culture[74]

- Sugar Labs[75]

- SustainableUnion[76]

- Sverok[77]

- TestPAC[78]

- TopCoder[10]

- Ubuntu[79]

- [80]

- Volt Europe[81]

- Wikipedia in French,[15] Hebrew,[82] Hungarian,[83] Russian,[84] and Persian.[85]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Markus Schulze, A new monotonic, clone-independent, reversal symmetric, and condorcet-consistent single-winner election method, Social Choice and Welfare, volume 36, number 2, page 267–303, 2011. Preliminary version in Voting Matters, 17:9-19, 2003.

- ^ Under reasonable probabilistic assumptions when the number of voters is much larger than the number of candidates

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Douglas R. Woodall, Properties of Preferential Election Rules, Voting Matters, issue 3, pages 8-15, December 1994

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Anti-plurality, Coombs and Dodgson are assumed to receive truncated preferences by apportioning possible rankings of unlisted alternatives equally; for example, ballot A > B = C is counted as A > B > C and A > C > B. If these methods are assumed not to receive truncated preferences, then later-no-harm and later-no-help are not applicable.

- ^ Tideman, T. Nicolaus, "Independence of clones as a criterion for voting rules," Social Choice and Welfare vol 4 #3 (1987), pp 185-206.

- ^ See:

- Markus Schulze, Condorect sub-cycle rule, October 1997

- Mike Ossipoff, Party List P.S., July 1998

- Markus Schulze, Tiebreakers, Subcycle Rules, August 1998

- Markus Schulze, Maybe Schulze is decisive, August 1998

- Norman Petry, Schulze Method - Simpler Definition, September 1998

- Markus Schulze, Schulze Method, November 1998

- ^ See:

- Anthony Towns, Disambiguation of 4.1.5, November 2000

- Norman Petry, Constitutional voting, definition of cumulative preference, December 2000

- ^ Jump up to: a b See:

- ^ Jump up to: a b See:

- 2009 Gentoo Council Election Results, December 2009

- 2010 Gentoo Council Election Results, June 2010

- 2011 Gentoo Council Election Results, June 2011

- 2012 Gentoo Council Election Results, June 2012

- 2013 Gentoo Council Election Results, June 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b 2007 TopCoder Collegiate Challenge, September 2007

- ^ See:

- 2008 Board Elections, June 2008

- 2009 Board Elections, August 2009

- 2011 Board Elections, June 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b section 3.4.1 of the Rules of Procedures for Online Voting

- ^ Jump up to: a b See:

- Inför primärvalen, October 2009

- Dags att kandidera till riksdagen, October 2009

- Råresultat primärvalet, January 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b 11 of the 16 regional sections and the federal section of the Pirate Party of Germany are using LiquidFeedback for unbinding internal opinion polls. In 2010/2011, the Pirate Parties of Neukölln (link), Mitte (link), Steglitz-Zehlendorf (link), Lichtenberg (link), and Tempelhof-Schöneberg (link) adopted the Schulze method for its primaries. Furthermore, the Pirate Party of Berlin (in 2011) (link) and the Pirate Party of Regensburg (in 2012) (link) adopted this method for their primaries.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Choix dans les votes

- ^ fr:Spécial:Pages liées/Méthode Schulze

- ^ Chumich, Andrew. "DSA Special Election". Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ Article 7.1.3 of its Working Format of the Agora, p. 54, July 2016

- ^ Election of the Annodex Association committee for 2007, February 2007

- ^ Ajith, Van Atta win ASG election, April 2013

- ^ §6 and §7 of its bylaws, May 2014

- ^ §6(6) of the bylaws

- ^ §9a of the bylaws, October 2013

- ^ See:

- 2013 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, January 2014

- 2014 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, January 2015

- 2015 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, March 2016

- 2016 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, January 2017

- 2017 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, February 2018

- 2018 Golden Geek Awards - Nominations Open, March 2019

- ^ [1], January 2021

- ^ Civics Meeting Minutes, March 2012

- ^ Adam Helman, Family Affair Voting Scheme - Schulze Method

- ^ See:

- Candidate cities for EBTM05, December 2004

- Meeting location preferences, December 2004

- Date for EBTM07 Berlin, January 2007

- Vote the date of the Summer EBTM08 in Ljubljana, January 2008

- New Logo for EBT, August 2009

- ^ "Guidance Document". Eudec.org. 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ Democratic election of the server admins Archived 2015-10-02 at the Wayback Machine, July 2010

- ^ Campobasso. Comunali, scattano le primarie a 5 Stelle, February 2014

- ^ Fondi, il punto sui candidati a sindaco. Certezze, novità e colpi di scena, March 2015

- ^ article 25(5) of the bylaws, October 2013

- ^ 2° Step Comunarie di Montemurlo, November 2013

- ^ article 12 of the bylaws, January 2015

- ^ Ridefinizione della lista di San Cesareo con Metodo Schulze, February 2014

- ^ article 57 of the statutory rules

- ^ Voters Guide, September 2011

- ^ See:

- Verbale della Free Hardware Foundation, June 2008

- Poll Results, June 2008

- ^ §7(3) of the voting rules, November 2015

- ^ GnuPG Logo Vote, November 2006

- ^ "User Voting Instructions". Gso.cs.binghamton.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ Haskell Logo Competition, March 2009

- ^ "Hillegass-Parker House Bylaws § 5. Elections". Hillegass-Parker House website. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ section 9.4.7.3 of the Operating Procedures of the Address Council of the Address Supporting Organization

- ^ article VI section 10 of the bylaws, November 2012

- ^ A club by any other name ..., April 2009

- ^ See:

- Ka-Ping Yee, Condorcet elections, March 2005

- Ka-Ping Yee, Kingman adopts Condorcet voting, April 2005

- ^ Knight Foundation awards $5000 to best created-on-the-spot projects, June 2009

- ^ Kubuntu Council 2013, May 2013

- ^ See:

- Mascot 2010 and program cover 2009 contests, May 2009

- Mascot 2011 and book cover 2010 contests, May 2010

- Mascot 2012 and book cover 2011 contests, May 2011

- 2013 Mascot Contest, March 2012

- 2014 Mascot Contest, April 2013

- ^ article 8.3 of the bylaws

- ^ The Principles of LiquidFeedback. Berlin: Interaktive Demokratie e. V. 2014. ISBN 978-3-00-044795-2.

- ^ "Madisonium Bylaws - Adopted". Google Docs.

- ^ "Wahlmodus" (in German). Metalab.at. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ Benjamin Mako Hill, Voting Machinery for the Masses, July 2008

- ^ See:

- Wahlen zum Neo-2-Freeze: Formalitäten Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine, February 2010

- Hinweise zur Stimmabgabe, March 2010

- Ergebnisse, March 2010

- ^ bylaws, September 2014

- ^ "2009 Director Elections". noisebridge.net.

- ^ "Online Voting Policy". openembedded.org.

- ^ See:

- 2010 OpenStack Community Election, November 2010

- OpenStack Governance Elections Spring 2012, February 2012

- ^ Election Process, June 2016

- ^ National Congress 2011 Results, November 2011

- ^ §6(10) of the bylaws

- ^ The Belgian Pirate Party Announces Top Candidates for the European Elections, January 2014

- ^ bylaws

- ^ Rules adopted on 18 December 2011

- ^ Verslag ledenraadpleging 4 januari, January 2015

- ^ "23 January 2011 meeting minutes". pirateparty.org.nz.

- ^ Piratenversammlung der Piratenpartei Schweiz, September 2010

- ^ article IV section 3 of the bylaws, July 2012

- ^ Committee Elections, April 2012

- ^ Squeak Oversight Board Election 2010, March 2010

- ^ See:

- Bylaws of the Students for Free Culture, article V, section 1.1.1

- Free Culture Student Board Elected Using Selectricity, February 2008

- ^ Election status update, September 2009

- ^ §10 III of its bylaws, June 2013

- ^ Minutes of the 2010 Annual Sverok Meeting, November 2010

- ^ article VI section 6 of the bylaws

- ^ Ubuntu IRC Council Position, May 2012

- ^ "/v/GAs - Pairwise voting results". vidyagaemawards.com.

- ^ "Paneuropean Party of Volt".

- ^ See e.g. here [2] (May 2009), here [3] (August 2009), and here [4] (December 2009).

- ^ See here and here.

- ^ "Девятнадцатые выборы арбитров, второй тур" [Result of Arbitration Committee Elections]. kalan.cc. Archived from the original on 2015-02-22.

- ^ See here

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schulze method. |

- The Schulze Method of Voting by Markus Schulze

- Condorcet Computations by Johannes Grabmeier

- Spieltheorie (in German) by Bernhard Nebel

- Accurate Democracy by Rob Loring

- Christoph Börgers (2009), Mathematics of Social Choice: Voting, Compensation, and Division, SIAM, ISBN 0-89871-695-0

- Nicolaus Tideman (2006), Collective Decisions and Voting: The Potential for Public Choice, Burlington: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-4717-X

- preftools by the Public Software Group

- Arizonans for Condorcet Ranked Voting

- Condorcet PHP Command line application and PHP library, supporting multiple Condorcet methods, including Schulze.

- Implementation in Java

- Implementation in Ruby

- Implementation in Python 2

- Implementation in Python 3

- Debian

- Monotonic Condorcet methods

- Single-winner electoral systems

![d[V,W]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8df7b4860300a09074531dd82e43a04f4179cd09)

![{\displaystyle i=1,\cdots ,(n-1):d[C(i),C(i+1)]>d[C(i+1),C(i)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/633580d95b3ca0ba9e5304f44cfdd20768586480)

![{\displaystyle i=1,\cdots ,(n-1):d[C(i),C(i+1)]\geq p}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f8ee2ae6fc070591eaf802af374bae9120d1c180)

![p[A,B]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2db36f2c916152b48d8c762329032136698cd2f1)

![p[A,B] = 0](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e1012483d213c4cce23e162a1707bc628281af06)

![p[D,E] > p[E,D]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d9233aadb2fe52f7da0d3b78922887242f43c5a4)

![{\displaystyle p[D,E]\geq p[E,D]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cfb3cce2eb9fad83d31d37a1aa9c13116881b2a3)

![p[X,Y] > p[Y,X]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/888212514ef5f6aab86a6e178a74bf64285570ac)

![p[Y,Z] > p[Z,Y]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/07668824ec7d421e6c4ba93cdb1113bd31c89161)

![p[X,Z] > p[Z,X]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2a289a31ba341ad5972484971896b7ade6887206)

![d[A, B] = 20](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/616fefcb8235a491fddf453df155781c9af635b9)

![d[B, A] = 25](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/df14406da203e08b0a7de3d10fc3c4741ff5f2be)

![d[*,A]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d2433862a5da2042a5aa511a40d9ae3937fa80da)

![d[*,B]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d9a569a62e7e27ec155cdea7128dd9716bbbafad)

![d[*,C]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/051eb2e238d95060533be1d80a7dc129ffaae071)

![d[*,D]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6365f00dc82da401f2dacf3811636c0f04e74b76)

![d[*,E]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/510965cc123e859a1bd6c9f7b0b3a6fd9c7ef10f)

![d[A,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e5e073ed6786afc665e2ae51f57b48780ab1b97e)

![d[B,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dddd58b0010e6b9e833d9c16ea3a92a0f0e0b60e)

![d[C,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1f3df13a469557e873323bdd8d90f51fd60975be)

![d[D,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3d181d2f3490676b9488069ae533aa12620ff560)

![d[E,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/404d8e35f83c4ea952ae013139f2cf0ed6724db9)

![p[*,A]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7ed62bbfc48846cad8299f1ae2cbd73539776e7)

![p[*,B]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/333750cdd31bc0ef53aae51b21a4a940adf6ae82)

![p[*,C]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2bc85a3d9d6ba41f0bc19b56087c96f375226f93)

![p[*,D]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cec9a2f8ae04fc767a071a03bd0ea9caa6644fe2)

![p[*,E]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cadbd7f5d672332d9f9cf60a84f33e6655191c6c)

![p[A,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d4c21f5b64afaf82d43e8721055de525787e983)

![p[B,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7022a11349de2d0fc5af2f3f820b1beca2d191f8)

![p[C,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/96902cfcb1a6c52549e109378f3975ac1e67b24f)

![p[D,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f99b88bf3741f0817bb81d0955904c5a6bde9d1e)

![p[E,*]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7b3f4b64482d398508522ebbddad2ebbe18cdf0e)

![(28 =) p[A,B] > p[B,A] (= 25)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5102460dac92bbf79a731ebea0174b87e2dbc302)

![(31 =) p[E,D] > p[D,E] (= 24)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/db687fa2ae0ee4b059387c4eb8665b88c88e0237)

![p[E,X] \ge p[X,E]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a93b3547fa268c146f1723b3c2327d148e926562)