Single transferable vote

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

The single transferable vote (STV) is a voting system designed to achieve or closely approach proportional representation through the use of multiple-member constituencies and each voter casting a single ballot on which candidates are ranked. The preferential (ranked) balloting allows transfer of votes to produce proportionality, to form consensus behind select candidates and to avoid the waste of votes prevalent under other voting systems.[1] Another name for STV is multi-winner ranked-choice voting.[2]

Under STV, each elector (voter) casts a single vote in a district election that elects multiple winners. Each elector marks their ballot for the most preferred candidate and also marks back-up preferences. A vote goes to the voter's first preference if possible, but if the first preference is eliminated, instead of being thrown away, the vote is transferred to a back-up preference, with the vote being assigned to the voter's second, third, or lower choice if possible (or under some systems being apportioned fractionally to different candidates).

Where there are more candidates than seats, the least popular is eliminated and their votes transferred based on voters' marked back-up preferences. In some systems surplus votes not needed by successful candidates are transferred proportionally, as described below. Elections and/or eliminations, and vote transfers where applicable, continue until enough candidates are declared elected or until there are only as many remaining candidates as there are unfilled seats, at which point the remaining candidates are declared elected.

The specific method of transferring votes varies in different systems (see § Quota and vote transfers).

STV enables votes to be cast for individual candidates rather than for parties or party machine-controlled party lists. Compared to first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting, STV reduces the number of "wasted" votes, which are those cast for unsuccessful candidates and for successful candidates over and above those needed to secure a seat. STV avoids this waste by transferring a vote to another preferred candidate.

STV also provides approximately proportional representation, ensuring that substantial minority factions have some representation. No one party or voting block can take all the seats in a district. The key to STV's achievement of proportionality is that each elector (voter) only casts one single vote, in a district election electing multiple winners.

Under STV, district elections grow more proportionally representative in direct relation to increase in the number of seats to be elected in a constituency – the more seats, the more the distribution of the seats in a district will be proportional. For example, in a three-seat STV election using the Hare Quota of , a candidate or party needs 33 percent of the votes to win a seat. In a seven-seat STV district, any candidate who can get the support of approximately 14 percent of the vote (either first preferences alone or a combination of first preferences and lower-ranked preferences transferred from other candidates) will win a seat.

Instant runoff voting (IRV) is the single-winner analogue of STV. It is also called "single-winner ranked-choice voting". Its goal is representation of a majority of the voters in a district by a single official, as opposed to STV's goal of proportional representation of all the substantial voting blocks by multiple officials.

Terminology[]

When STV is used for single-winner elections, it is equivalent to the instant-runoff voting method.[3] STV used for multi-winner elections is sometimes called "proportional representation through the single transferable vote", or PR-STV. "STV" usually refers to the multi-winner version, as it does in this article. In the United States, it is sometimes called choice voting, preferential voting, or preference voting. ("Preferential voting" can also refer to a broader category, ranked voting systems.)

Hare-Clark is the name given to PR-STV elections in Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.

Voting[]

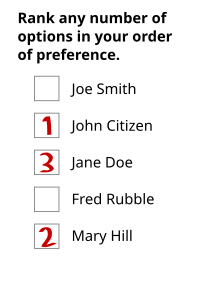

In STV, each voter ranks the candidates in order of preference, marking a '1' beside their most preferred candidate, a '2' beside their second most preferred, and so on as shown in the sample ballot on the right. As noted, this is a simplified example. In practice, the candidates' names are usually organized in columns so that voters are informed of the candidates' party affiliations or whether they are standing as independents. (An alternative way to mark preferences for candidates is to use columns for the voters' preference. One column is to show first preference. An X there goes beside the most preferred candidate. The next column is for the second preference. An X there marks the second-preference candidate., etc.)

Filling seats under STV[]

The use of quota to fill seats[]

In most STV elections, a quota is established to ensure that all elected candidates are elected with approximately equal numbers of votes. In some STV varieties, votes are totalled, and a quota (the minimum number of votes required to win a seat) is derived.[a] Another similarly flexible system set quota at 25 percent of the votes in a district.[4]

Once a quota is determined, candidates' vote tallies are consulted. If a candidate achieves the quota, he or she is declared elected. Then in some STV systems, any surplus vote is transferred to other candidates in proportion to the next back-up preference marked on the ballots received by that candidate. If more candidates than seats remain, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, with their votes being transferred to other candidates as determined by the voters' next back-up preference. Elections and/or eliminations, and vote transfers where applicable, continue until enough candidates are declared elected or until there are only as many remaining candidates as there are unfilled seats, at which point the remaining candidates are declared elected. These last candidates may be elected without surpassing quota, but their survival until the end is taken as proof of their general acceptability by the voters.

It can be shown that a candidate requires a minimum number of votes – the quota (or threshold) – to be elected. A number of different quotas can be used; the most common is the Droop quota, given by the floor function formula:

The Droop quota is an extension of requiring a 50% + 1 majority in single-winner elections. For example, at most three people can have 25% + 1 in 3-winner elections, 9 can have 10% + 1 in 9-winner elections, and so on.

If fractional votes can be submitted, then the Droop quota may be modified so that the fraction is not rounded down. Major Frank Britton, of the Election Ballot Services at the Electoral Reform Society, observed that the final plus one of the Droop quota is not needed; the exact quota is then simply . Without fractional votes, the equivalent integer quota may be written:

So, the quota for one seat is 50 of 100 votes, not 51.[5]

Finding winners using quota[]

An STV election count starts with a count of each voter's first choice, recording how many for each candidate, calculation of the total number of votes and the quota and then taking the following steps:

- A candidate who has reached or exceeded the quota is declared elected.

- If any such elected candidate has more votes than the quota, surplus votes are then transferred to other candidates proportionally based on their next indicated choice on all the ballots that had been received by that candidate. This can be done in several ways (see § Quota and vote transfers ).

- If no-one has exceeded the quota or after all surplus votes have been transferred, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the votes are transferred to the next preferred candidate marked on each ballot.

- This process repeats until either every seat has been filled by candidates surpassing quota or until there are as many remaining seats as there are remaining candidates, at which point the remaining candidates are declared elected.

There are variations, such as how to transfer surplus votes from winning candidates and whether to transfer votes to already-elected candidates. When the number of votes transferred from the losing candidate with the fewest votes is too small to change the ordering of remaining candidates, more than one candidate can be eliminated simultaneously.

One simplistic formula for how to transfer surplus votes is:

however, this can produce fractional votes, which are handled differently under different counting methods.

If the variation of STV used allows transfers to candidates already elected, when a candidate is eliminated and the next preference on the ballot shows preference for a candidate already elected, votes are transferred to already victorious candidate. The new surplus votes for the victorious candidate (transferred from the eliminated candidate) are then transferred to the next preference of the victorious candidate, as happened with their initial surplus. However, any vote transfers from the victorious candidate to a candidate who was already eliminated are impossible, and reference must be made to the next marked preference, if any. See § Filling seats under STV for details.

Because votes cast for losing candidates and surplus votes cast for winning candidates are transferred to voters' next choice candidates, STV minimizes wasted votes.

Quota and vote transfers[]

STV systems primarily differ in how they transfer votes and in the size of the quota. For this reason some have suggested that STV can be considered a family of voting systems rather than a single system.

The quota, if used, must be set so that no more candidates can reach quota than there are seats to be filled. The Droop quota is the most commonly used quota. It being relatively low means that the largest party is likely to take the majority of the seats in a district. The Hare quota, which was used in the original proposals by Thomas Hare,[6] ensures greater representation to less-popular parties within a district.

The easiest methods of transferring surpluses involve an element of randomness; partially random systems, such as the Hare system, are used in the Republic of Ireland (except Senate elections) and in Malta, among other places. The Gregory method (also known as Newland-Britain or Senatorial rules) eliminates randomness by allowing for the transfer of fractions of votes. Gregory is in use in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland (Senate elections) and in Australia. Both Gregory and earlier methods have the problem that in some circumstances they do not treat all votes equally. For this reason Meek's method, Warren's method and the Wright system have been invented.[7] While easier methods can usually be counted by hand, except in a very small election Meek and Warren require counting to be conducted by computer.[citation needed] The Wright system is a refinement of the Australian Senate system replacing the process of distribution and segmentation of preferences by a reiterative counting process where the count is reset and restarted on every exclusion. Meek is used in local body elections in New Zealand.

Meek in 1969[8] was the first to realize that computers make it possible to count votes in way that is conceptually simpler and closer to the original concept of STV. One advantage of Meek's method is that the quota is adjusted at each stage of counting when the number of votes decreases because some become non-transferable. Meek also considered a variant on his system which allows for equal preferences to be expressed.[9] This has subsequently (since 1998) been used by the John Muir Trust for electing its trustees.[10]

Example[]

Suppose an election is conducted to determine what three foods to serve at a party. There are 5 candidates, 3 of which will be chosen. The candidates are Oranges, Pears, Chocolate, Strawberries, and Hamburgers. The 20 guests at the party mark their ballots according to the table below. In this example, a second choice is made by only some of the voters.

| # of guests | x x x x | x x | x x x x x x x x |

x x x x | x | x |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st preference |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2nd preference |

|

|

|

First, the quota is calculated. Using the Droop quota, with 20 voters and 3 winners to be found, the number of votes required to be elected is:

- .

When ballots are counted the election proceeds as follows:

| Candidate |

|

|

|

|

|

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | x x x x | x x | x x x x x x x x x x x x |

x | x | Chocolate is declared elected, since Chocolate has more votes than the quota (with six surplus votes, to be precise). |

| Round 2 | x x x x | x x | x x x x x x |

x x x x x |

x x x | Chocolate's surplus votes transfer to Strawberry and Hamburgers in proportion to the Chocolate voters' second choice preferences, using the formula:

In this case, 8 of the 12 voters for Chocolate had the second preference of Strawberries, so (8/12)•6 = 4 of Chocolate's votes would transfer to Strawberries; meanwhile 4 of the 12 voters for Chocolate had Hamburgers as their second preference, so (4/12)•6 = 2 of Chocolate's votes will transfer to Hamburgers. Thus, Strawberries has 1 first-preference votes and 4 new votes, for an updated total of 1 + 4 = 5 votes; likewise, Hamburgers now has 1 + 2 = 3 votes; no other tallies change. Even with the transfer of this surplus no candidate has reached the quota. Therefore, Pear, which now has the fewest votes (after the update), is eliminated. |

| Round 3 | x x x x x x |

YES | x x x x x |

x x x | Pear's votes are transferred in proportion to the second-preference options of voters of Pear, i.e. only Oranges in this case, which gives Oranges 2 more votes. Oranges now totals 4 (original) + 2 (new) = 6 votes, reaching the quota; so, Oranges is elected. Orange meets the quota exactly, and therefore has no surplus to transfer. | |

| Round 4 | YES | YES | x x x x x |

x x x | Neither of the remaining candidates meets the quota, so again the lowest candidate (in this case Hamburgers) is eliminated. This leaves Strawberries as the only remaining candidate, so it wins the final seat (despite not satisfying the quota).

(If there were still unfilled seats, Hamburgers' votes would be transferred proportionately based on next preferences, if there were any indicated. So Chocolate-then-Hamburgers votes that had gone to Hamburgers cannot be transferred again as only two preferences were selected. And no one who voted for Hamburgers originally gave a second preference.) |

Result: The winners are Chocolate, Oranges and Strawberries. This result differs from the one that would have occurred if the three winners were decided by first preference plurality rankings, in which case Pear would have been a winner as opposed to Strawberry for having a greater number of first preference votes.

History and current use[]

Origin[]

The concept of transferable voting was first proposed by Thomas Wright Hill in 1819. The system remained unused in public elections until 1855, when Carl Andræ proposed a transferable vote system for elections in Denmark, and his system was used in 1856 to elect the Rigsraad and from 1866 it was also adapted for indirect elections to the second chamber, the Landsting, until 1915.[11]

Although he was not the first to propose transferable votes, the English barrister Thomas Hare is generally credited with the conception of STV, and he may have independently developed the idea in 1857. Hare's view was that STV should be a means of "making the exercise of the suffrage a step in the elevation of the individual character, whether it be found in the majority or the minority." In Hare's original system, he further proposed that electors should have the opportunity of discovering which candidate their vote had ultimately counted for, to improve their personal connection with voting.[6] At the time of Hare's original proposal, the UK did not use the secret ballot, so not only could the voter determine the ultimate role of their vote in the election, the elected MPs would have been able to determine who had voted for them. As Hare envisaged that the whole House of Commons be elected "at large" this would have replaced geographical constituencies with what Hare called "constituencies of interest" – those people who had actually voted for each MP. In modern elections, held by secret ballot, a voter can discover how their vote was distributed by viewing detailed election results. This is particularly easy to do using Meek's method, where only the final weightings of each candidate need to be published. The elected member is, however, unable to verify whom their supporters were.

The noted political essayist John Stuart Mill was a friend of Hare's and an early proponent of STV, praising it at length in his essay Considerations on Representative Government, in which he writes: "Of all modes in which a national representation can possibly be constituted, this one affords the best security for the intellectual qualifications desirable in the representatives. At present... the only persons who can get elected are those who possess local influence, or make their way by lavish expenditure...."[12] His contemporary, Walter Bagehot, also praised the Hare system for allowing everyone to elect an MP, even ideological minorities, but also argued that the Hare system would create more problems than it solved: "[the Hare system] is inconsistent with the extrinsic independence as well as the inherent moderation of a Parliament – two of the conditions we have seen, are essential to the bare possibility of parliamentary government."[13]

Advocacy of STV spread throughout the British Empire, leading it to be sometimes known as British Proportional Representation. In 1896, Andrew Inglis Clark was successful in persuading the Tasmanian House of Assembly to be the first parliament in the world elected by what became known as the Hare-Clark electoral system, named after himself and Thomas Hare. H. G. Wells was a strong advocate, calling it "Proportional Representation".[14] The HG Wells formula for scientific voting, repeated, over many years, in his PR writings, to avoid misunderstanding, is Proportional Representation by the single transferable vote in large constituencies.[15]

STV in large constituencies permits an approach to the Hare-Mill-Wells ideal of mirror representation. The UK National Health Service used to elect, First Past The Post, all white male General Practitioners. In 1979, STV proportionally represented women, immigrants and specialists, to the General Medical Council.[16]

Australia[]

In 1948, single transferable vote proportional representation on a state-by-state basis became the method for electing Senators to the Australian Senate. This change has led to the rise of a number of minor parties such as the Democratic Labor Party, Australian Democrats and Australian Greens who have taken advantage of this system to achieve parliamentary representation and the balance of power. From the 1984 election, group ticket voting was introduced to reduce a high rate of informal voting but in 2016, group tickets were abolished to avoid undue influence of preference deals amongst parties that were seen as distorting election results[17] and a form of optional preferential voting was introduced.

Beginning in the 1970s, Australian states began to reform their upper houses to introduce proportional representation in line with the Federal Senate. The first was the South Australian Legislative Council in 1973, which initially used a party list system (replaced with STV in 1982),[18] followed by the single transferable vote being introduced for the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1978,[19] the Western Australian Legislative Council in 1987[20] and the Victorian Legislative Council in 2003.[21] The single transferable vote was also introduced for the elections to the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly after a 1992 referendum.[22]

The term STV in Australia refers to the Senate electoral system, a variant of Hare-Clark characterized by the "above the line" group voting ticket, a party list option. It is used in the Australian upper house, the Senate, most state upper houses, the Tasmanian lower house and the Capital Territory assembly. There is a compulsory number of preferences for a vote for candidates (below-the-line) to be valid: for the Senate a minimum of 90% of candidates must be scored, in 2013 in New South Wales that meant writing 99 preferences on the ballot.[23] Therefore, 95% and more of voters use the above-the-line option, making the system, in all but name, a party list system.[24][25][26] Parties determine the order in which candidates are elected and also control transfers to other lists and this has led to anomalies: preference deals between parties, and "micro parties" which rely entirely on these deals. Additionally, independent candidates are unelectable unless they form, or join, a group above-the-line.[27][28] Concerning the development of STV in Australia researchers have observed: "... we see real evidence of the extent to which Australian politicians, particularly at national levels, are prone to fiddle with the electoral system".[29]:86

As a result of a parliamentary commission investigating the 2013 election, from 2016 the system has been considerably reformed (see 2016 Australian federal election), with group voting tickets (GVTs) abolished and voters no longer required to fill all boxes.

Canada[]

This section does not cite any sources. (April 2021) |

In British Columbia, Canada, a type of STV called BC-STV was recommended for provincial elections by the British Columbia Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform in 2004. In a 2005 provincial referendum, it received 57.69 percent support and passed in 77 of 79 electoral districts. It was not adopted, however, because it fell short of the 60 percent threshold requirement the BC Liberal government had set for the referendum to be binding.[30] In a second referendum, on 12 May 2009, BC-STV was defeated 60.91 percent to 39.09 percent.

STV has been used in several Canadian jurisdictions. The cities of Edmonton and Calgary elected their MLAs through STV from 1924 to 1956, when the Alberta provincial government changed those elections to use first-past-the-post. The city of Winnipeg elected its MLAs through STV from 1920 to 1955, when the Manitoba provincial government changed those elections to use first-past-the-post.[31]

Less well known is STV use at the municipal level in western Canada. Calgary and Winnipeg used STV for more than 50 years before city elections were changed to first-past-the-post. Nineteen other municipalities, including the capital cities of the four western provinces, also used STV For elections in about 100 elections during the 1918 to 1931 period.

United States[]

In the United States, the Proportional Representation League was founded in 1893 to promote STV, and their efforts resulted in its adoption by many city councils in the first half of the 20th century. More than twenty cities have used STV, including Cleveland, Cincinnati and New York City. As of January 2010, it is used to elect the city council and school committee in Cambridge, Massachusetts and the park board in Minneapolis, Minnesota. STV has also been adopted for student government elections at several American universities, including Carnegie Mellon,[32][33] MIT, Oberlin, Reed, UC Berkeley, UC Davis, Vassar, UCLA, Whitman, and UT Austin. The Fair Representation Act, introduced in Congress in June 2017, would establish STV for US House elections starting in 2022.[34]

Places using STV[]

STV has had its widest adoption in the English-speaking world. As of 2019, in government elections, STV is used for:

| Australia | Federal (country-wide) | Senate elections (since 1948[b] – with the option of using a group voting ticket from 1983 until 2016) |

| Australian Capital Territory | Legislative Assembly elections (since 1992) | |

| Norfolk Island | Local government elections (since 2016) | |

| Northern Territory | Local government elections (since 2011) | |

| New South Wales | Legislative Council elections (since 1978 – with the option of using a group voting ticket until 2003) Local government elections (since 2012) | |

| South Australia | Legislative Council elections (since 1982 – with the option of using a group voting ticket from 1985 until 2017) Local government elections (since 1999) | |

| Tasmania | House of Assembly elections (since 1896) Local government elections (since 1993) | |

| Victoria | Legislative Council elections (since 2003 – with the option of using a group voting ticket) Local government elections (since 2003) | |

| Western Australia | Legislative Council elections (since 1987 – with the option of using a group voting ticket) | |

| India | Indirect elections – presidential, vice-presidential, Rajya Sabha and Vidhan Parishad (in few states) elections. | |

| Ireland | Dáil general elections (lower house; since 1921[c]) Seanad general elections (upper house; since 1925) European elections (since 1979) Local government elections (since 1920[d]) | |

| Malta | Parliamentary elections (since 1921) European elections Local government elections | |

| Nepal | Indirect elections – Upper house elections (by provinces and local assemblies) since 2018 | |

| New Zealand[35] |

Regional council elections: Wellington Regional Council Later additions – Hamilton City Council (2020)[37] | |

| Pakistan | Indirect elections – Senate elections (by members of provincial assemblies, and direct vote by the population of territories) | |

| United Kingdom | Northern Ireland | Northern Ireland Assembly elections[e] Local government elections |

| Scotland | Local government elections (since May 2007) | |

| United States | City elections in Cambridge, Massachusetts (multi-member, at-large district), Eastpointe, Michigan and Palm Desert, California

At-large municipal board seats[38] in Minneapolis, Minnesota Historically during the Progressive Era in 21 other cities between 1915 and 1960, including New York City for New York City Council from 1937 to 1947 (multi-winner districts)[39][40] | |

Benefits and drawbacks[]

Benefits[]

Advocates[who?] for STV argue it is an improvement over winner-take-all non-proportional voting systems such as first-past-the-post, where vote splits commonly result in a majority of voters electing no one and the successful candidate having support from just a minority of the district voters. STV prevents in most cases one party taking all the seats and in its thinning out of the candidates in the field prevents the election of an extreme candidate or party if it does not have enough overall general appeal.

STV is the system of choice of the Proportional Representation Society of Australia (which calls it quota-preferential proportional representation),[41] the Electoral Reform Society in the United Kingdom[42] and FairVote in the USA (which refers to STV as fair representation voting[43] and instant-runoff voting as "ranked-choice voting",[44] although there are other preferential voting methods that use ranked-choice ballots).

Drawbacks[]

Critics[who?] contend that some voters find the mechanisms behind STV difficult to understand, but this does not make it more difficult for voters to rank the list of candidates in order of preference on an STV ballot paper (see § Voting).[45]

Critics also see a vote transfer process that is more time-consuming than in first-past-the-post elections where the result is known within a few hours and say it is not worth using STV just to have more proportional results. However, STV's supporters say that some winners are known in the same period as under FPTP, and that with delays under FPTP caused by mail-in or absentee ballots, any delays in an STV scenario are not noticeable or are no great hardship.[citation needed]

Issues[]

Degree of proportionality[]

The degree of proportionality of STV election results depends directly on the district magnitude (i.e. the number of seats in each district). While Ireland originally had a median district magnitude of five (ranging from three to nine) in 1923, successive governments lowered this. Systematically lowering the number of representatives from a given district directly benefits larger parties at the expense of smaller ones.

Supposing that the Droop quota is used: in a nine-seat district, the quota or threshold is 10% (plus one vote); in a three-seat district, it would be 25% (plus one vote).

A parliamentary committee in 2010 discussed the "increasing trend towards the creation of three-seat constituencies in Ireland" and recommended not less than four-seaters, except where the geographic size of such a constituency would be disproportionately large.[46]

STV provides proportionality by transferring votes to minimize waste, and therefore also minimizes the number of unrepresented or disenfranchised voters.

Difficulty of implementation[]

A frequent concern about STV is its complexity compared with plurality voting methods. Before the advent of computers, this complexity made ballot-counting more difficult than for some other voting methods.

The algorithm is complicated. In large elections with many candidates, a computer may be required. (This is because after several rounds of counting, there may be many different categories of previously transferred votes, each with a different permutation of early preferences and thus each with a different carried-forward weighting, all of which have to be kept track of.)

Role of political parties[]

STV differs from other proportional representation systems in that candidates of one party can be elected on transfers from voters for other parties. Hence, STV may reduce the role of political parties in the electoral process and corresponding partisanship in the resulting government. A district only needs to have four members to be proportional for the major parties, but may under-represent smaller parties, even though they may well be more likely to be elected under STV than under first past the post.

By-elections[]

As STV is a multi-member system, filling vacancies between elections can be problematic, and a variety of methods have been devised:

- The countback method is used in the Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania, Victoria, Malta, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Casual vacancies can be filled by re-examining the ballot papers data from the previous election.

- Another option is to have a head official or remaining members of the elected body appoint a new member to fulfill the vacancy.

- A third way to fill a vacancy is to hold a single-winner by-election (effectively instant runoff); this allows each party to choose a new candidate and all voters to participate. This is the method used in the Republic of Ireland in national elections, and in Scotland's local elections.

- Yet another option is to allow the party of the vacant member to nominate a successor, possibly subject to the approval of the voting population or the rest of the government. This is the method used in the Republic of Ireland in local elections.[47]

- Another possibility is to have the candidates themselves create an ordered list of successors before leaving their seats. In the European Parliament, a departing member from the Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland is replaced with the top eligible name from a replacement list submitted by the candidate at the time of the original election. This method was also used in the Northern Ireland Assembly, until 2009, when the practice was changed to allow political parties to nominate new MLAs in the event of vacancies. Independent MLAs may still draw up lists of potential replacements.[48]

- For its 2009 European elections, Malta introduced a one-off policy to elect the candidate eliminated last to fill the prospective vacancy for the extra seat that arose from the Lisbon Treaty.

Tactics[]

If there are not enough candidates to represent one of the priorities the electorate vote for (such as a party), all of them may be elected in the early stages, with votes being transferred to candidates with other views. On the other hand, putting up too many candidates might result in first preference votes being spread too thinly among them, and consequently several potential winners with broad second-preference appeal may be eliminated before others are elected and their second-preference votes distributed. In practice, the majority of voters express preference for candidates from the same party in order,[citation needed] which minimizes the impact of this potential effect of STV.

The outcome of voting under STV is proportional within a single election to the collective preference of voters, assuming voters have ranked their real preferences and vote along strict party lines (assuming parties and no individual independents participate in the election). However, due to other voting mechanisms usually used in conjunction with STV, such as a district or constituency system, an election using STV may not guarantee proportionality across all districts put together.

A number of methods of tactical or strategic voting exist that can be used in STV elections, but much less so than with First Past the Post. (In STV elections, most constituencies will be marginal, at least with regard to the allocation of a final seat.)

Elector confusion[]

STV systems vary, both in ballot design and in whether or not voters are obliged to provide a full list of preferences. In jurisdictions such as Malta, Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, voters may rank as many or as few candidates as they wish. Consequently, voters sometimes, for example, rank only the candidates of a single party, or of their most preferred parties. A minority of voters, especially if they do not fully understand the system, may even "bullet vote", only expressing a first preference, or indicate a first preference for multiple candidates, especially when both STV and plurality are being used in concurrent elections.[49] Allowing voters to rank only as many candidates as they wish grants them greater freedom, but can also lead to some voters ranking so few candidates that their vote eventually becomes "exhausted"–that is, at a certain point during the count, it can no longer be transferred and therefore loses an opportunity to influence the result.

The method can be confusing, and may cause some people to vote incorrectly with respect to their actual preferences. The ballots can also be long; having multiple pages also increases the chances of people missing the later opportunities to continue voting.[clarification needed]

Other[]

Some opponents[who?] argue that larger, multi-seat districts would require more campaign funds to reach the voters. Proponents argue that STV can lower campaign costs because like-minded candidates can share some expenses. Proponents reason that negative advertising is disincentivized in such a system, as its effect is diluted among a larger pool of candidates. In addition, candidates do not have to secure the support of at least 50% of voters, allowing candidates to focus campaign spending primarily on supportive voters.

Analysis of results[]

Academic analysis of voting systems such as STV generally centres on the voting system criteria that they pass. No preference voting system satisfies all the criteria in Arrow's impossibility theorem: in particular, STV fails to achieve independence of irrelevant alternatives (like most other vote-based ordering systems) and monotonicity.[citation needed]

Migration of preferences[]

The relative performance of political parties in STV systems is analysed in a different fashion from that used in other electoral schemes. For example, seeing which candidates are declared elected on first preference votes alone can be shown as follows:

| Party | Total elected | Elected on 1st prefs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | % (2007) | |||

| Conservative | 115 | 46 | 40.0 | 40.6 | |

| Labour | 394 | 199 | 50.5 | 37.4 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 71 | 20 | 28.2 | 21.7 | |

| SNP | 425 | 185 | 43.5 | 56.5 | |

| Green | 14 | 1 | 7.1 | – | |

| Independent | 200 | 79 | 39.5 | 31.6 | |

| Other | 4 | 2 | 50.0 | 14.3 | |

| Totals | 1,223 | 532 | 43.5 | 39.7 | |

The data can also be analysed to find the proportion of voters who express only a single preference,[51] or those who express a minimum number of preferences,[52] to assess party strength. Where parties nominate multiple candidates in an electoral district, analysis can also be done to assess their relative strength.[53]

Other useful information can be found by analysing terminal transfers—i.e., when the votes of a candidate are transferred and no other candidate from that party remains in the count[52]—especially with respect to the first instance in which that occurs:

| Transferred from | % non-transferable | % transferred to | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | Lab | LD | SNP | Ind/Other | |||

| Conservative | 33.6 | – | 8.0 | 32.4 | 8.3 | 17.6 | |

| Labour | 47.8 | 5.8 | – | 13.2 | 16.5 | 16.7 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 23.1 | 21.8 | 20.4 | – | 15.5 | 19.3 | |

| SNP | 44.2 | 6.0 | 18.1 | 14.1 | – | 17.8 | |

| Green | 20.4 | 5.1 | 19.2 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 17.0 | |

Another effect of STV is that candidates who did well on first preference votes may not be elected, and those who did poorly on first preferences can be elected, because of differences in second and later preferences. This can also be analysed:

| Political party | Elected though not in top 3 or 4 |

Not elected though in top 3 or 4 |

Net gain/loss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2007 | ||||

| Conservative | 1 | 16 | −15 | −24 | |

| Labour | 21 | 8 | +13 | −17 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 4 | 3 | +1 | +29 | |

| SNP | 19 | 29 | −10 | – | |

| Green | 1 | 1 | – | +1 | |

| Independent | 22 | 9 | +13 | +8 | |

| Other | – | 2 | −2 | +3 | |

See also[]

- Tally (voting)

- None of the above

- Approval voting

- Single non-transferable vote

- Table of voting systems by country

- Collective transferable vote

- Voting matters, a journal concerned with the technical aspects of STV

Notes[]

- ^ In some implementations, a quota is simply set by law – any candidate receiving a given number of votes is declared elected. Under this system, used in New York City in the 1930s to 1940s, the number of representatives elected varies with voter turnout.

- ^ STV was previously used to elect the Tasmanian members of both the Senate and the House of Representatives in the inaugural 1901 federal election.

- ^ STV was previously used for the Dublin University constituency in the 1918 general election.

- ^ STV was previously used for the 1919 special election for Sligo Corporation.

- ^ STV was previously used for the 1921 and 1925 elections to the Northern Ireland parliament.

References[]

- ^ "Single Transferable Vote". Electoral Reform Society.

- ^ FairVote.org. "Ranked Choice Voting / Instant Runoff". FairVote. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ http://www.fairvote.org/how_rcv_works Note that when used to elect a multiple candidates to office, ranked choice voting (RCV or IRV) is a form of fair representation voting, and it may be called single transferable vote or STV.

- ^ Sandford Fleming, Essays on the Rectification of Parliament (1892)

- ^ Newland 1984.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lambert & Lakeman 1955, p. 245.

- ^ Hill, Wichmann & Woodall 1987.

- ^ Meek 1994a.

- ^ Meek 1994b.

- ^ "Examples of STV elections". hw.ac.uk.

- ^ "Andræs metode | Gyldendal – Den Store Danske". denstoredanske.dk.

- ^ Mill 1861, p. 144.

- ^ Bagehot 1894,

p. 158.

p. 158.

- ^ Wells 1918, pp. 121–129.

- ^ HG Wells 1916: The Elements of Reconstruction. HG Wells 1918: In The Fourth Year.

- ^ Electoral Reform Society, 1979 audit, which records the gratitude of the British medical profession for introducing STV.

- ^ Anderson, Stephanie (25 April 2016). "Senate Voting Changes Explained in Australian Electoral Commission Advertisements". ABC News. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Dunstan, Don (1981). Felicia: The political memoirs of Don Dunstan. Griffin Press Limited. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0-333-33815-4.

- ^ "Role and History of the Legislative Assembly". Parliament of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Electoral Reform expected to alter balance of power, The Australian, 11 June 1987, p.5

- ^ Constitution (Parliamentary Reform) Act 2003

- ^ "1992 Referendum". www.elections.act.gov.au. 6 January 2015.

- ^ "The Hare-Clark System of Proportional Representation". Melbourne: Proportional Representation Society of Australia. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Above the line voting". Perth: University of Western Australia. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Glossary of Election Terms". Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Hill, I.D. (November 2000). "How to ruin STV". Voting Matters (12). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Green, Anthony (20 April 2005). "Above or below the line? Managing preference votes". Australia: On Line Opinion. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Terry, Chris (5 April 2012). "Serving up a dog's breakfast". London: Electoral Reform Society. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ David M. Farrell; Ian McAllister (2006). The Australian Electoral System: Origins, Variations, and Consequences. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0868408583.

- ^ "Report of the Chief Electoral Office" (PDF).

- ^ A Report on Alberta Elections (1982)

- ^ "Elect@CMU | About single transferable voting". Carnegie Mellon University.

- ^ Gund, Devin. "CMU Fair Ranked Voting".

- ^ Donald, Beyer (14 July 2017). "H.R.3057 – 115th Congress (2017–2018): Fair Representation Act". www.congress.gov.

- ^ "Single Transferable Vote". Department of Internal Affairs. 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "STV Information". www.stv.govt.nz. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Hamilton City Council switches to STV system for elections". Stuff. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "What offices are elected using Ranked-Choice Voting?". What is Ranked-Choice Voting?. City of Minneapolis Elections & Voter Services. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ FairVote.org. "Learning from the past to prepare for the future: RCV in NYC". FairVote. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "History of RCV". Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Proportional Representation and its Importance". Proportional Representation Society of Australia.

- ^ "Our mission". Electoral Reform Society. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Fair Representation Voting". FairVote.

- ^ "Ranked Choice Voting". FairVote.

- ^ Margetts 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Ireland 2010, p. 177.

- ^ "Local Elections Regulations, 1965. Section 87". S.I. No. 128/1965 – Local Elections Regulations, 1965.

- ^ "Change to the System for Filling Vacancies in the NI Assembly" (Press release). Northern Ireland Office. 10 February 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ Ombler 2006.

- ^ Curtice 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Curtice 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Curtice 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Curtice 2012, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Curtice 2012, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Curtice 2012, p. 23.

Bibliography[]

- Bagehot, Walter (1894) [1867]. (7th ed.). London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. – via Wikisource.

- Curtice, John (2012). "2012 Scottish Local Government Elections" (PDF). London: Electoral Reform Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Hill, I. D.; Wichmann, B. A.; Woodall, D. R. (1987). "Algorithm 123: Single Transferable Vote by Meek's Method". The Computer Journal. 30 (3): 277–281. doi:10.1093/comjnl/30.3.277. ISSN 1460-2067.

- Ireland. Oireachtas. Joint Committee on the Constitution (2010). Article 16 of the Constitution: Review of the Electoral System for the Election of Members to Dáil Éireann (PDF). Dublin: Stationery Office. ISBN 978-1-4064-2501-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- Lambert, Enid; Lakeman, James D. (1955). Voting in Democracies. London: Faber and Faber.

- Margetts, Helen (2003). "Electoral Reform". In Fisher, Justin; Denver, David; Benyon, John (eds.). Central Debates in British Politics. Abingdon, England: Routledge (published 2014). pp. 64–82. ISBN 978-0-582-43727-2.

- Meek, B. L. (1994a). "A New Approach to the Single Transferable Vote. Paper I: Equality of Treatment of Voters and a Feedback Mechanism for Vote Counting". Voting Matters (1): 1–7. ISSN 1745-6231. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ——— (1994b). "A New Approach to the Single Transferable Vote. Paper II: The Problem of Non-transferable Votes". Voting Matters (1): 7–11. ISSN 1745-6231. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Mill, John Stuart (1861). Considerations on Representative Government. London: Parker, Son, and Bourn. ISBN 9781414254685. Retrieved 20 June 2014 – via Google Books.

- Newland, Robert A. (1984). "The STV Quota". Representation. 24 (95): 14–17. doi:10.1080/00344898408459347. ISSN 0034-4893.

- Ombler, Franz (2006). "Booklet Position Effects, and Two New statistics to Gauge Voter Understanding of the Need to Rank Candidates in Preferential Elections" (PDF). Voting Matters (21): 12–21. ISSN 1745-6231. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Wells, H. G. (1918). In the Fourth Year: Anticipation of a World Peace. London: Chatto & Windus. Retrieved 6 May 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- Bach, Stanley (2003). Platypus and Parliament: The Australian Senate in Theory and Practice. Department of the Senate. ISBN 978-0-642-71291-2.

- Ashworth, H.P.C.; Ashworth, T.R. (1900). Proportional Representation Applied to Party Government. Melbourne: Robertson and Co.

Further reading[]

- Bartholdi, John J., III; Orlin, James B. (1991). "Single Transferable Vote Resists Strategic Voting" (PDF). Social Choice and Welfare. 8 (4): 341–354. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.127.97. doi:10.1007/BF00183045. ISSN 0176-1714. JSTOR 41105995. S2CID 17749613. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Benade, Gerdus; Buck, Ruth; Duchin, Moon; Gold, Dara; Weighill, Thomas (2021). "Ranked Choice Voting and Minority Representation" (PDF). SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3778021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- Geller, Chris (2002). "Single Transferable Vote with Borda Elimination: A New Vote-Counting System" (PDF). Deakin University, Faculty of Business and Law.

- ——— (2004). "Single Transferable Vote with Borda Elimination: Proportional Representation, Moderation, Quasi-chaos and Stability". Electoral Studies. 24 (2): 265–280. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2004.06.004. ISSN 1873-6890.

- O'Neill, Jeffrey C. (2004). "Tie-Breaking with the Single Transferable Vote" (PDF). Voting Matters (18): 14–17. ISSN 1745-6231. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Sawer, Marian & Miskin, Sarah (1999). Papers on Parliament No. 34 Representation and Institutional Change: 50 Years of Proportional Representation in the Senate (PDF). Department of the Senate. ISBN 0-642-71061-9.

- Stone, Bruce (2008). "State legislative councils: designing for accountability." In N. Aroney, S. Prasser, & J. R. Nethercote (Eds.), Restraining Elective Dictatorship (PDF). UWA Publishing. pp. 175–195. ISBN 978-1-921401-09-1.

External links[]

- ACE Project

- A concise STV analogy – from Accurate Democracy

- Accurate Democracy lists a dozen programs for computing the single transferable vote.

- Australia's Upper Houses – ABC Rear Vision A podcast about the development of Australia's upper houses into STV elected chambers.

- Single transferable vote

- Non-monotonic electoral systems

- Preferential electoral systems

- Proportional representation electoral systems

- Electoral systems

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&{\text{transferred votes given to the next preference}}\\[6pt]={}&\left({\frac {\text{votes for next preference belonging to the original candidate}}{\text{total votes for the original candidate}}}\right)\times {\text{surplus votes for original candidate}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1c6748dc10339d5d475cc6a1ead7a017a4d79310)