Swat District

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2019) |

Swat

سوات | |

|---|---|

Springtime photograph of the Swat River running through the valley, May 2015 | |

| Nickname(s): Switzerland of the East[1] | |

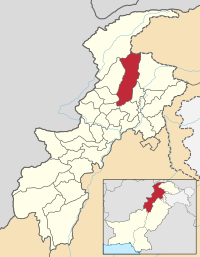

Swat District, highlighted red, shown within the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | |

| Coordinates: 35°12′N 72°29′E / 35.200°N 72.483°ECoordinates: 35°12′N 72°29′E / 35.200°N 72.483°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Capital | Saidu Sharif |

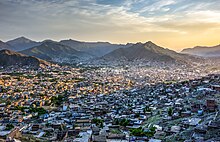

| Largest city | Mingora |

| Government | |

| • Chief Commissioner | N/A |

| • Deputy Commissioner | N/A |

| Area | |

| • District | 5,337 km2 (2,061 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • District | 2,309,570 |

| • Density | 430/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 695,900 |

| • Rural | 1,613,670 |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PKT) |

| Area code(s) | Area code 0946 |

| Languages (1981)[3] |

|

Swat District (Urdu: ضلع سوات, Pashto: سوات ولسوالۍ, pronounced [ˈswaːt̪]) is a district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. With a population of 2,309,570 per the 2017 national census, Swat is the 15th-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Swat District is centered on the Valley of Swat, usually referred to simply as Swat, which is a natural geographic region surrounding the Swat River. The valley was a major centre of early Hinduism and Buddhism under the ancient kingdom of Gandhara, and was a major centre of Gandharan Buddhism, with pockets of Buddhism persisting in the valley until the 10th century, after which the area became largely Muslim.[4][5] Until 1969, Swat was part of the Yusafzai State of Swat, a self-governing princely state that was inherited by Pakistan following its independence from British rule. The region was seized by the Tehrik-i-Taliban in late-2007 until Pakistani control was re-established in mid-2009.[6][7]

The average elevation of Swat is 980 m (3,220 ft),[5] resulting in a considerably cooler and wetter climate compared to the rest of Pakistan. With lush forests, verdant alpine meadows, and snow-capped mountains, Swat is one of the country's most popular tourist destinations.[8][9]

Etymology[]

The district and valley take their name from the Swat River. The ultimate etymology of the river's name is unclear. The Swat River in the Rigveda is referred to as the Suvāstu - with a literal meaning "of fair dwellings,"[10][11][12] which has been opined to refer to the presence of Aryan settlements along the river's course.[13] Some have suggested the Sanskrit name may mean "clear blue water."[14] Another theory derives the word Swat from the Sanskrit word shveta (lit. 'white'), also used to describe the clear water of the Swat River.[15] To the ancient Greeks, the river was known as the Soastus.[16][17][18][15] The Chinese pilgrim Faxian referred to Swat as the Su-ho-to.[19]

Geography[]

Swat's total area is 5,337 square kilometres (2,061 sq mi). In terms of administrative divisions, Swat is surrounded by Chitral, Upper Dir and Lower Dir to the west, Gilgit-Baltistan to the north, and Kohistan, Buner and Shangla to the east and southeast, respectively. The former tehsil of Buner was granted the status of a separate district in 1991.[20]

Valley[]

The Valley of Swat is delineated by natural geographic boundaries, and is centered on the Swat River, whose headwaters arise in the 18,000-19,000 foot tall Hindu Kush. The valley is enclosed on all sides by mountains, and is intersected by glens and ravines.[21] Above mountains ridges to the west is the valley of the Panjkora River, to the north the Gilgit Valley, and Indus River gorges to the east. To the south, across a series of low mountains, lies the wide Peshawar valley.[22]

The northernmost area of Swat district are the high valleys and alpine meadows of Swat Kohistan, a region where numerous glaciers feed the Usho, and Gabral rivers (also known as the Utrar River), which form a confluence at Kalam, and thereafter forms the Swat river - which forms the spine of the Swat Valley and district. Swat then is characterized by thick forests along the narrow gorges of the Kalam Valley until the city of Madyan. From there, the river courses gently for 160 km through the wider Yousufzai Plains of the lower Swat Valley until Chakdara.

Climate[]

Climate in Swat is a function of altitude, with mountains in the Kohistan region snow-clad year round. Upper reaches of the district are subject to cold, snowy winters. Drier, warmer temperatures in the lower portions of the district in the Yousafzai Plains where summer temperatures can reach 105 °F (41 °C), although the lower plains experience occasional snow.[21] Both regions are subject to two monsoon seasons - one in winter and the other in summer. Swats lower reaches have vegetation characterized by dry bush and deciduous trees, while upper reaches of the district have thick pine forests.[22]

Falak Sar, Swat's tallest mountain at 5,957 metres (19,544 ft)

Mount Mankial, which rises to 18,600 feet (5,700 m)

Pine forests occur in Swat at altitudes over 5,000 feet (1,500 m)

The northernmost region of Swat - a region known as Kohistan - has high alpine valley at the base of tall mountains

Jarogo Waterfall, in middle Swat

Alpine lakes, such as Mahodand Lake are found in the mountains of Swat Kohistan.

Alpine meadows in Utror

History[]

Aryan[]

The earliest recorded history of the region, preserved through the oral tradition, was the settlement and societies of the Indo-Aryan peoples. According to some, the name for the Swat River that was recorded in the Rig Veda, Suvāstu, which may mean "fair dwellings," refers to the presence of Aryan settlements in the region.[13] The Gandhara grave culture that emerged c. 1400 BCE and lasted until 800 BCE,[23] and named for their distinct funerary practices, was found along the Middle Swat River course. Later movements of the Indo-Aryan tribes saw the emergence of ethnic Nuristani and Dardic populations.[24]

Greek[]

In 327 BCE, Alexander the Great fought his way to Odigram and Barikot and stormed their battlements; in Greek accounts, these towns are identified as Ora and Bazira. After the Alexandrian invasion of Swat, and adjacent regions of Buner, control of the wider Gandhara region was handed to Seleucus I Nicator.

Gandhara[]

In 305 BCE, the Mauryan Emperor conquered the wider region from the Greeks, and probably established control of Swat, until their control of the region ceased around 187 BCE.[25] It was during the rule of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka that Buddhism was introduced into Swat,[26] and some of the earliest stupas built in the region.

Following collapse of Mauryan rule, Swat came under control of the Greco-Bactrians, and briefly the Scythians of the Central Asian Steppe.[27]

The region of Gandhara (based in the Peshawar valley and the adjacent hilly regions of Swat, Buner, Dir, and Bajaur), broke away from Greco-Bactrian rule to establish their own independence as the Indo-Greek Kingdom.[28] Following the death of the most famous Indo-Greek king, Menander I around 140 BCE, the region was overrun by the Indo-Scythians, and then the Persian Parthian Empire around 50 CE. The arrival of the Parthians began the long tradition of Greco-Buddhist art, which was a syncretic form of art combining Buddhist imagery with heavy Hellenistic-Greek influences. This art form is credited with having the first representations of the Buddha in human form, rather than symbolically.[citation needed]

The Parthians were ousted from Swat by the Kushans, based in the Peshawar valley. Kushan rule began what is considered by many to be the golden age of Gandhara. Under the greatest Kushan king, Kanishka, Swat became an important region for the production of Buddhist art, and numerous Buddhists shrines were built in the area. As a patron of Mahayana Buddhism, new Buddhists stupas were built and old ones were enlarged. The Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hsien, who visited the valley around 403 CE, mentions 500 monasteries.[29]

Butkara Stupa may have first been built during Mauryan rule in the 2nd century BCE

Amlukdara Stupa was built around the 3rd century CE, and is one of many Buddhist ruins in Swat

Nemogram Stupa, dating from the Kushan period c. 2-3 centuries CE, with many of its statues on display at the Swat Museum

Shingardar Stupa, a 27 meter tall stupa that is built along the main road that enters into Swat from the Peshawar Valley.[30]

Shamozi Stupa

Hephthalite[]

Swat and the wider region of Gandhara were overrun by the Iranian Hephthalites around about 465 CE.[31] Under the rule of Mihirakula, Buddhism was suppressed as he himself became virulently anti-Buddhist after a perceived slight against him by a Buddhist monk.[32] Under his rule, Buddhist monks were reportedly killed, and Buddhist shrines attacked.[32] He himself appears to have been inclined towards the Shaivism sect of Hinduism.[32]

In around 520 CE, the Chinese monk Song Yun visited the area, and recorded that area had been in ruin and ruled by a leader that did not practice the laws of the Buddha.[33] The Tang-era Chinese monk Xuanzang recorded the decline of Buddhism in the region, and ascendance of Hinduism in the region. According to him, of the 1400 monasteries that had supposedly been there, most were in ruins or had been abandoned.[34]

Hindu Shahi[]

Following the collapse of Buddhism in Swat following the Hephthalite invasion, Swat was ruled by the Hindu Shahi dynasty beginning in the 8th century,[35] who made their capital at Udigram in lower Swat.[35] The Shahis built an extensive array of temples and other architectural buildings, of which ruins remain today. Under their rule, Hinduism ascended, and Sanskrit is believed to have been the lingua franca of the locals during this time.[36] By the time of the Muslim conquests (c. 1000 CE), the population in the region was predominantly Hindu,[37]:19 though Buddhism persisting in the valley until the 10th century, after which the area became largely Muslim.[4][5] Hindu Shahi rulers built fortresses to guard and tax the commerce through this area,[38] and ruins dating back to their rule can be seen on the hills at the southern entrance of Swat, at the Malakand Pass.[39]

Muslim rule[]

Around 1001 CE, the last Hindu Shahi king, Jayapala was decisively defeated at the Battle of Peshawar (1001) by Mahmud of Ghazni, thereby ending 2 centuries of Hindu rule over Gandhara. Sometime later, ethnic Swatis entered the area along with Sultans from Kunar (present-day Afghanistan).

Yousafzai State of Swat[]

The Yousafzai State of Swat was a kingdom established in 1849 by the Muslim saint Akhund Abdul Gaffur, more commonly known as Saidu Baba,[40][37] that was ruled by chiefs known as Akhunds. It was then recognized as a princely state in alliance with the British Indian Empire between 1926 and 1947, after which the Akhwand acceded to the newly independent state of Pakistan. Swat continued to exist as an autonomous region until it was dissolved in 1969,[41] and incorporated into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (formerly called NWFP).

Taliban rule[]

The region was seized by the Tehrik-i-Taliban in late-2007,[6] and its highly-popular tourist industry was subsequently decimated until Pakistani control was re-established in mid-2009 after a month-long campaign.[7] During their occupation, the Taliban attacked Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai in 2012, who at the time was a young school-girl who wrote a blog for BBC Urdu detailing life under Taliban rule, and their curb on girls' education.

Kushan-era Buddhist stupas and statues in the Swat Valley were demolished by the Taliban,[42][dead link] and the Jehanabad Buddha's face was blown up using dynamite,[43][44] but was repaired by a group of Italian restorers in a nine-year-long process.[45] The Taliban and looters subsequently destroyed many of Pakistan's Buddhist artifacts,[46] and deliberately targeted Gandhara Buddhist relics for destruction.[47] Gandhara artifacts remaining from the demolitions were thereafter plundered by thieves and smugglers.[48]

Economy[]

Approximately 38% of economy of Swat depends on tourism[49] and 31% depends on agriculture.[50]

Agriculture[]

Gwalerai village located near Mingora is one of those few villages which produces 18 varieties of apples due to its temperate climate in summer. The apple produced here is consumed in Pakistan as well as exported to other countries. It is known as ‘the apple of Swat’.[51] Swat is famous for peach production mostly grown in the valley bottom plains and accounts for about 80% of the peach production of the country. Mostly marketed in the national markets with a brand name of "Swat Peaches". The supply starts in April and continues till September because of a diverse range of varieties grown.

Demographics[]

The population of Swat District is 2,309,570 as per the 2017 census, making it the third-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after Peshawar District and Mardan District.[52] With the exception of the uppermost regions of the valley, which are inhabited by Dardic Kohistanis, Swat is mostly inhabited by Yusufzai Pashtuns.[5] The language spoken in the valley is Pashto (mainly the Yousafzai dialect), with a minority of Torwali and Kalami speakers in the Swat Kohistan region of Upper Swat.

Education[]

According to the Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings for 2017, Swat District with a score of 53.1, is ranked 86 out of 155 districts in terms of education. Furthermore, school infrastructure score is 90.26 ranking the district at number 31 out of 155 districts.[53]

Tribes[]

- Pashtuns

- Gujjars[54]

Administrative divisions[]

The District of Swat is subdivided into 7 tehsils:[55]

- Babuzai

- Matta

- Khwaza Khela

- Barikot

- Kabal

- Charbagh

- Bahrain

Each tehsil comprises certain numbers of union councils. There are 65 union councils in the district: 56 rural and 9 urban.

According to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act, 2013,[56] a new local governments system was introduced, in which Swat District is included. This system has 67 wards, in which the total amount of village councils are around 170, while neighbourhood councils number around 44.[57]

Politics[]

The region elects three male members of the National Assembly of Pakistan (MNAs), one female MNA, seven male members of the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (MPAs)[58] and two female MPAS. In the 2002 National and Provincial elections, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal, an alliance of religious political parties, won all the seats.

Provincial Assembly[]

| Member of Provincial Assembly | Party Affiliation | Constituency | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharafat Ali | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-2 Swat-I | 2018 |

| Sardar Khan | Pakistan Muslim League (N) | PK-3 Swat-II | 2018 |

| Aziz Ullah Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-4 Swat-III | 2018 |

| Fazal Hakeem Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-5 Swat-IV | 2018 |

| Amjad Ali | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PPK-6 Swat-V | 2018 |

| Waqar Ahmad Khan | Awami National Party | PK-7 Swat-VI | 2018 |

| Mohib Ullah Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-8 Swat-VII | 2018 |

| Mahmood Khan | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | PK-9 Swat-VIII | 2018 |

Notable people[]

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2019) |

- Mubarika Yusufzai

- Wāli of Swat

- Mahmood Khan

- Malala Yousafzai

- Ziauddin Yousafzai

- Muhib Ullah Khan

- Anwar Ali

- Nazia Iqbal

- Ghazala Javed

- Afzal Khan Lala

- Haider Ali Khan

- Malak Jamroz Khan

- Rahim Khan

- Ancestors of Bollywood actor Salman Khan hail from Swat Valley

- Nasirul Mulk

- Badar Munir

- Murad Saeed

- Shaheen Sardar Ali

- Rahim Shah

- Sherin Zada

See also[]

- Akhund of Swat

- Lower Swat Valley

- Oḍḍiyāna

- Swat (princely state)

- Lower Dir District

- Upper Dir District

- Chitral District

- Buner District

- Kaghan Valley

- Kohistan District

- 1974 Hunza earthquake

- Operation Black Thunderstorm

- Operation Rah-e-Rast

- 2009 refugee crisis in Pakistan

- Pushtu People

- Barikot

References[]

- ^ Steven stee 2013.

- ^ "DISTRICT AND TEHSIL LEVEL POPULATION SUMMARY WITH REGION BREAKUP: KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Stephen P. Cohen (2004). The Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press. p. 202. ISBN 0815797613.

- ^ Jump up to: a b East and West, Volume 33. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. 1983. p. 27.

According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist Orgyan pa forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375) ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70 ).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mohiuddin, Yasmeen Niaz (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851098019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Abbas, Hassan (24 June 2014). The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300178845.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Craig, Tim (9 May 2015). "The Taliban once ruled Pakistan's Swat Valley. Now peace has returned". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Khaliq, Fazal (17 January 2018). "Tourists throng Swat to explore its natural beauty". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "The revival of tourism in Pakistan". Daily Times. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1900). A History of Sanskrit Literature. D. Appleton.

the Suvastu, river "of fair dwellings" (now Swat)

- ^ Vidyalankar, Satyakam (1977). R̥gveda Saṃhitā. Veda Pratishthan.

The word suvastu means “ having fair dwellings '

- ^ Roy, S. B. (1989). Early Aryans of India, 3100-1400 B.C. Navrang. ISBN 978-81-7013-052-9.

, Suvastu ( Swat or with fair dwellings )

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laet, Sigfried J. de; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1 January 1994). History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3.

The word suvastu signifying 'fair dwellings' seems to indicate that there were Aryan settlements along its banks.

- ^ Susan Whitfield (2018). Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road. University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-520-95766-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sultan-i-Rome (2008). Swat State (1915–1969) from Genesis to Merger: An Analysis of Political, Administrative, Socio-political, and Economic Development. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-547113-7.

- ^ bart.), sir Edward Herbert Bunbury (9th (1879). A history of ancient geography among the Greeks and Romans. J. Murray.

- ^ Arrian (14 February 2013). Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-958724-7.

- ^ Saxena, Savitri (1995). Geographical Survey of the Purāṇas: The Purāṇas, a Geographical Survey. Nag Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7081-333-0.

- ^ Rienjang, Wannaporn; Stewart, Peter (15 March 2019). The Geography of Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd-23rd March, 2018. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-78969-187-0.

- ^ 1998 District Census report of Buner. Census publication. 98. Islamabad: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan. 2000. p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paget, William Henry (1874). A Record of the Expeditions Undertaken Against the North-west Frontier Tribes. Superintendent of government printing.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barth, Fredrik (8 September 2020). Political Leadership Among Swat Pathans: Volume 19. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-32448-8.

- ^ Olivieri, Luca M., Roberto Micheli, Massimo Vidale, and Muhammad Zahir, (2019). 'Late Bronze - Iron Age Swat Protohistoric Graves (Gandhara Grave Culture), Swat Valley, Pakistan (n-99)', in Narasimhan, Vagheesh M., et al., "Supplementary Materials for the formation of human populations in South and Central Asia", Science 365 (6 September 2019), pp. 137-164.

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. ISBN 9781884964985.

- ^ Callieri, Pierfrancesco (1997). Saidu Sharif I (Swat, Pakistan). IsMEO.

Having brought under its domination part of Afghanistan and , most probably , Swat ( Tucci 1978 ) , the Maurya dynasty died out around 187 BC

- ^ Khan, Makin (1997). Archaeological Museum Saidu Sharif, Swat: A Guide. M. Khan.

- ^ Ahmad, Makhdum Tasadduq (1962). Social Organization of Yusufzai Swat: A Study in Social Change. Panjab University Press.

They ruled this area for nearly 150 years when they were replaced first by Bactrians and latter by the Scythians

- ^ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (24 June 2010). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-00941-6.

- ^ Petrie, Cameron A. (28 December 2020). Resistance at the Edge of Empires: The Archaeology and History of the Bannu basin from 1000 BC to AD 1200. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-304-1.

- ^ Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-860-8.

- ^ Atreyi Biswas (1971). The Political History of the Hūṇas in India. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Singh, Upinder (25 September 2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97527-9.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1958). Early History of North India, from the Fall of the Mauryas to the Death of Harsa, C. 200 B.C.-A.D. 650. Progressive Publishers.

- ^ Wriggins, Sally (11 June 2020). Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim On The Silk Road. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-01109-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khaliq, Fazal (6 March 2016). "Castle of last Hindu king Raja Gira in Swat crumbling". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Sorrow and Joy Among Muslim Women The Pushtuns of Northern Pakistan By Amineh Ahmed Published by Cambridge University Press, 2006 Page 21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fredrik Barth, Features of Person and Society in Swat: Collected Essays on Pathans, illustrated edition, Routledge, 1981

- ^ Marati, Ivano; Vassallo, Candida Maria (2013). The New Swat Archaeological Museum: Construction activities in Swat district (2011-2013) Khyber-Pakthunkhwa, Pakistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications. ISBN 978-969-35-2664-6.

- ^ Swat: An Afghan Society in Pakistan: Urbanisation and Change in Tribal Environment By Inam-ur-Rahim, Alain M. Viaro Published by City Press, 2002 Page 59

- ^ S.G. Page 398 and 399, T and C of N.W.F.P by Ibbetson page 11 etc

- ^ Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Ann Mills, Margaret (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 447. ISBN 9780415939195.

- ^ "Taliban defeated by the quiet strength of Pakistan's Buddha". Times of India.

- ^ Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013). I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Little, Brown. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-316-32241-6.

The Taliban destroyed the Buddhist statues and stupas where we played Kushan kings haram Jehanabad Buddha.

- ^ Wijewardena, W.A. (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But then, we all are Malalas, aren't we?". Daily FT.

- ^ Khaliq, Fazal (7 November 2016). "Iconic Buddha in Swat valley restored after nine years when Taliban defaced it". DAWN.

- ^ "Taliban and traffickers destroying Pakistan's Buddhist heritage". AsiaNews.it. 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Taliban trying to destroy Buddhist art from the Gandhara period". AsiaNews.it. 27 November 2009.

- ^ Rizvi, Jaffer (6 July 2012). "Pakistan police foil huge artefact smuggling attempt". BBC News.

- ^ https://korbah.com/hotels/?location_name=Swat&location_id=9694&start=&end=&date=19%2F01%2F2020+12%3A00+am-20%2F01%2F2020+11%3A59+pm&room_num_search=1&adult_number=1&child_number=0&price_range=0%3B23250&taxonomy%5Bhotel_facilities%5D=

- ^ Chief Editor. "Swat Economy". kpktribune.com. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Amjad Ali Sahaab. "Gwalerai — The little village behind Swat's famous apples". dawn.com. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Swat District – Population of Cities, Towns, and Villages 2017–2018". Pakistan's Political Workers Helpline. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017" (PDF). elections.alifailaan.pk. Alif Ailaan. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Ann Mills, Margaret (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 447. ISBN 9780415939195.

- ^ http://lgkp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Village-Neighbourhood-Councils-Detatails-Annex-D.pdf

- ^ http://lgkp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Local-Government-Elections-Rules-2013.pdf

- ^ "Village/Neighbourhood Council". Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Constituencies and MPAs – Website of the Provincial Assembly of the N-W.F.P". Archived from the original on 28 December 2007.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swat District. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Swat. |

Bibliography[]

- Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013), I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban, Little, Brown, ISBN 9780316322416

- Swat District

- Hill stations in Pakistan

- Valleys of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- Indus basin

- Buddhism in Pakistan