Tallulah, Louisiana

Tallulah, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Tallulah | |

Tallulah municipal building | |

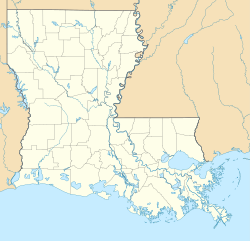

Location of Tallulah in Madison Parish, Louisiana | |

Tallulah, Louisiana Location of Tallulah in Madison Parish, Louisiana | |

| Coordinates: 32°24′31″N 91°11′12″W / 32.40861°N 91.18667°WCoordinates: 32°24′31″N 91°11′12″W / 32.40861°N 91.18667°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Madison |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gloria Hayden (interim for Paxton J. Branch, who died on September 1, 2018)[2] |

| • City Council | show

City Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.78 sq mi (7.21 km2) |

| • Land | 2.78 sq mi (7.21 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 85 ft (26 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,335 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 6,666 |

| • Density | 2,395.26/sq mi (924.79/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 71282, 71284 |

| FIPS code | 22-74690 |

| Website | cityoftallulah |

Tallulah is a small city in, and the parish seat of, Madison Parish in northeastern Louisiana, United States.[5] The 2010 population was 7,335, a decrease of 1,854, or 20.2 percent, from the 9,189 recorded at the 2000 census.[6]

As this was historically a center of agriculture since the antebellum years, producing cotton and pecans, Tallulah and the parish have long had majority-African American populations. The small city is now nearly 77 percent African American; the surrounding parish is 60 percent black. Mechanization and industrial agriculture have reduced the number of jobs, and many residents have moved since the mid-20th century to larger cities with more opportunities.

Tallulah is the principal city of the Tallulah Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Madison Parish. The Madison Parish Sheriff's office operates the Steve Hoyle Rehabilitation Center in Tallulah.

History[]

This area was developed in the antebellum years by European Americans for cotton plantations. They brought in thousands of enslaved African Americans to produce and process the crops. Major planters grew wealthy from their labor at a time when the market for cotton was strong.

During the American Civil War, Union gunboats in Lake Providence headed south to Tallulah, where they burned the Vicksburg, Shreveport, and Texas Railroad's depot. They captured Confederate supplies awaiting shipment to Indian Territory, where some tribes were allied with the Confederacy. The Confederates in Tallulah offered no resistance. Afterward, numerous potential Confederate troops in the area had to be rejected for enlistment because of a lack of weapons.[7] During the Vicksburg Campaign, Union General Ulysses S. Grant's troops destroyed many structures in the parish. Some plantation homes, such as Hermione, were used as Union hospitals.

Post-Civil War to 1942[]

After the war, many freedmen from the plantations stayed in the parish, often working as sharecroppers. In the late 19th century, Italian immigrants settled in Louisiana, most in New Orleans but some in outlying parishes such as Madison. Some served as migrant workers on cotton or sugar cane plantations, in the north or south of the state, respectively. The immigrants were primarily from Sicily. Starting as farm workers, some banded together to establish small stores, such as groceries in county seats and other trading towns.

By 1899 five Sicilians were doing a good business in Tallulah, with four small stores devoted to fruit, vegetables and poultry. All but one of the men were relatives. Whites attacked the Sicilians because of economic competition.[8] They had also been criticized for failing to comply with Jim Crow rules: if they had black customers waiting, they made new white customers wait their turn rather than giving the whites preference, as was the custom.[9] On July 20, 1899, a mob of white residents of Tallulah lynched the five Sicilians from Cefalù. Two other Italians who lived in nearby Milliken's Bend fled the area for their safety. The Italians were still citizens (nationals) of Italy, and their government protested strongly to the United States government about each lynching murder. The US government said that the states had to prosecute such killings.[9] As was typical in this period of frequent lynchings of black US citizens, none of the white lynch mob was prosecuted.[8]

The city developed through the early 20th century and had a growing population, as people came in from rural areas to work in the lumber mills and timber processing. Because it was the center of a major agricultural area, Tallulah became the site of the Louisiana Delta Fair, held annually in October through the first half of the 20th century. It featured exhibits from Madison, East Carroll, and Tensas parishes. Later in the century, the fair was phased out.[10]

Shirley Field, also known as Scott Field, was reportedly the first airport in Louisiana; it was built in 1922 near Tallulah.[11][12] Dr. B.R. Coad, head of the Agricultural Experiment Laboratory, developed a process and equipment for crop dusting from airplanes, in order to combat the devastating boll weevil infestation of cotton crops. The USDA bought a Huff-Daland plane for this purpose in 1924.[12] Hundreds of flights took off from the Tallulah Airport as this process was developed, and fields on both sides of the Mississippi were treated. Delta Air Lines had its origins from Delta Dusters, the company developed here to produce and operate crop dusting from airplanes.[12] Shirley Field and the original airport building still stand near Tallulah, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[11]

The parish seat also attracted Jewish immigrants. Based on the success of their drugstore, in 1927 merchant brothers Mertie M. and Abe Bloom built the first enclosed shopping mall, Bloom's Arcade, in the United States in Tallulah. It was built by A. Hays Town in the style of European city arcades.[13] The building had a central hall, with stores located on either side, much like the ones today. The hall opened into the street on both ends. This landmark is still in Tallulah, located along what is now U.S. Route 80. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). As of late 2013, it has been restored to its original architectural character and was adapted as an apartment complex.[14]

Later in 1927, the downtown was flooded during the Great Flood of 1927. Many downtown stores were flooded by several feet of water. It took time for the town to recover.

World War II to present[]

After serving in World War II, African-American veterans began to challenge racial discrimination in the South more vigorously. After the Supreme Court ruled in Smith v. Allwright (1944) that the white primary of the Democratic Party was unconstitutional, more blacks began to register in the South. But in Louisiana the number of white qualified voters in 1947 still surpassed blacks by a ratio of 100 to one.[15]

The population increased in Tallulah in the decades after the war, reaching a high in 1980 (see tables below). African Americans were the majority population in the city and the parish. Having faced continuing discrimination in efforts to vote, in 1962 a group of eight African-American men successfully sued the parish registrar and state to be able to register and vote. Following passage of the national Civil Rights Act in 1964, in 1965, activists conducted boycotts to end discrimination in employment; many stores would not hire blacks as workers. Seventeen businesses closed in the city rather than hire blacks.[16][17] That year Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, authorizing the federal government to oversee voter registration and elections in jurisdictions such as Tallulah and Madison Parish with historic under-representation of minorities. The proportion of African-American voting began to increase.

In 1969 Zelma Wyche, a local veteran and activist, was elected as Police Chief of Tallulah, the first African American to hold the office. He ensured there were an equal number of white and black police officers on the force and had them patrol in mixed teams.[17]

In 1971, black candidates were running for 21 of 27 parish seats in Madison Parish, a sign of the changing times. In other parts of Louisiana, African Americans were also running for local offices.[18]

In 1974 Adell Williams was elected as mayor of Tallulah, the first African American to hold the office. He is believed to have been the first black mayor elected in Louisiana since Reconstruction.[19]

The city had its peak of population in 1980. The mechanization of agriculture and the decline of some former industries have reduced the number of local jobs, with population following. It used to be considered a lumber mill town, with the Chicago Mill and Lumber dominating local industry from its site on the west side of the city.[20] After declines from the 1970s, the mill closed in 1983, adding to local economic problems.[19]

Unlike in some areas of the state, only four antebellum structures remain in the parish, because of destruction by General Ulysses S. Grant's forces during the Vicksburg Campaign in the Civil War. One is a one-story 1855 plantation house, known as Hermione, from the Kell Plantation. It was used by Grant as a Union hospital.[21]

After being donated in 1997 to the Madison Historical Society, Hermione was moved to its current site on North Mulberry Street in Tallulah. It was adapted to serve both as offices for the society and as the Hermione Museum, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[21] Among its exhibits is one about Madam C. J. Walker, the first African-American woman to become a self-made businesswoman and millionaire.[22] Born free soon after the war as Sarah Breedlove in nearby Delta, Louisiana, she moved north as a young woman, where she developed a line of hair-care products that she manufactured and sold nationally. The museum is on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.[22]

On April 24, 2010, an EF4 tornado touched down just outside Tallulah, causing numerous injuries. The tornado also damaged a tanker in a chemical plant, causing a small nitrogen leak. Significant damage to an industrial plant with associated injuries, trapped people, and destroyed homes nearby were reported in Madison Parish near the Louisiana-Mississippi state line. The tornado continued across the Mississippi River. It gained strength and struck Yazoo, Holmes, and Choctaw counties in Mississippi, causing 10 fatalities and extensive destruction.[23][24]

Detention and correction facilities[]

In November 1994 the state opened the privately operated Tallulah Correctional Center for Youth on the western edge of the city. Residents hoped it would provide jobs for local people and aid the local economy, but there were soon problems associated with management of the facility, and the jobs there were low paying. In addition to problems within the facility, the prison seemed to have an adverse effect on the city. In 1999 the state took over operating the facility, renaming it as the Swanson Correctional Center for Youth/Madison Parish Unit but there continued to be problems with the treatment of youth.[19]

A coalition of townspeople began to work on ideas for different uses for the land. The state decided to close this facility, and the coalition proposed an educational center instead. They gained legislative approval in one year, so when the juvenile prison was closed in 2004, there were plans developed for an educational center on the site. A bill for the Northeast Delta Learning Center was signed by Governor Kathleen Blanco in July 2004. Issues remaining were getting funding for it and offsetting a proposal to use the facility as an adult prison.[19] Despite the desire of the townspeople, the facility was converted to house adult prisoners.[20] It is known as the Madison Parish Louisiana Transitional Center for Women (LCTW), houses 535 inmates, and is operated by LaSalle Corrections, a private company.[25]

Other related facilities in Tallulah, as it is the parish seat, are the Madison Parish Detention Center, with 264 inmates, and the Madison Parish Correctional Center, with 334 inmates. These are also operated by LaSalle Corrections.[26]

Seviers of Tallulah[]

Tallulah and Madison Parish have been led and represented politically by numerous members of the prominent Sevier family, who were longtime planters. They are descended from John Sevier, a veteran of the American Revolution, and his wife. Later they were pioneers in what is now Tennessee, and Sevier was elected as the first Governor of Tennessee. He was the namesake for the city of Sevierville, Tennessee.[27]

George Washington Sevier, Sr. (1858–1925) was elected as a member of the Madison Parish Police Jury. He served as the parish tax assessor from 1891 to 1916.[27] Except for the years 1887–90, there has been at least one member of the Sevier family in public office for the 122 years preceding 2005. The family's power was maintained primarily in the decades-long period when Democratic Party whites dominated voting, and Louisiana was virtually a one-party state. From its passage of a new constitution in 1898, the state legislature worked to disenfranchise African Americans, who were then mostly members of the Republican Party. They were systematically disenfranchised and nearly excluded from the political system until after passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-20th century.

Under these conditions, was repeatedly re-elected as a Democratic member of the Louisiana State Senate, serving from 1932 until his death in 1962. His widow, the former Irene Newman Jordan, was appointed to serve the rest of his term. Andrew Jackson Sevier, Jr., served as sheriff of Madison Parish from 1904 until his death in office in 1941. He was succeeded for the rest of his term by his widow, Mary Louise Day Sevier. A cousin of the Seviers, Henry Clay Sevier, was a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1936 to 1952.[27]

James D. Sevier, Sr., and his son, also named James, held the office of tax assessor for more than four decades. Mason Spencer, husband of Rosa Sevier Spencer, represented Madison Parish in the Louisiana House from 1924 to 1936. He planned to run for governor of Louisiana in 1935 but withdrew his candidacy after the assassination of former governor Huey Pierce Long, Jr. Richard Leche of New Orleans, of the Long faction, won the office.[27]

Among the political leaders from this family were William Putnam "Buck" Sevier, Jr., a banker. He first served three terms as an elected town alderman in Tallulah. He was elected as mayor of the city in 1946 and served for nearly 30 years, from 1947 to 1974. His tenure included some of the volatile years of the civil rights movement, when African Americans sought changes to the Jim Crow system and justice as citizens. Sevier led white residents in adapting to change as more African-American citizens began to register, vote and be elected to local offices. Sevier at the time of his death held the record, at more than forty-four years, as the longest-serving publicly elected official in Louisiana.[27]

Geography[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2), all land.

Climate[]

| hideClimate data for Tallulah, Louisiana (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1907–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

87 (31) |

106 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 59.6 (15.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

71.5 (21.9) |

79.1 (26.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

91.6 (33.1) |

94.2 (34.6) |

94.8 (34.9) |

90.2 (32.3) |

81.3 (27.4) |

69.9 (21.1) |

61.9 (16.6) |

78.7 (25.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 49.0 (9.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

59.9 (15.5) |

67.5 (19.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

81.6 (27.6) |

84.0 (28.9) |

84.0 (28.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

68.8 (20.4) |

57.9 (14.4) |

51.1 (10.6) |

67.5 (19.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 38.4 (3.6) |

41.0 (5.0) |

48.4 (9.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

64.8 (18.2) |

71.5 (21.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

46.0 (7.8) |

40.3 (4.6) |

56.4 (13.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−12 (−24) |

11 (−12) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

54 (12) |

52 (11) |

34 (1) |

21 (−6) |

15 (−9) |

4 (−16) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.63 (143) |

5.54 (141) |

5.34 (136) |

6.65 (169) |

4.49 (114) |

3.85 (98) |

4.29 (109) |

3.86 (98) |

3.28 (83) |

4.43 (113) |

4.68 (119) |

5.83 (148) |

57.87 (1,470) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.9 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 8.3 | 89.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Source: NOAA[28][29] | |||||||||||||

| showClimate data for Tallulah, Louisiana (Vicksburg – Tallulah Regional Airport) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present |

|---|

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 847 | — | |

| 1920 | 1,316 | 55.4% | |

| 1930 | 3,332 | 153.2% | |

| 1940 | 5,712 | 71.4% | |

| 1950 | 7,758 | 35.8% | |

| 1960 | 9,413 | 21.3% | |

| 1970 | 9,643 | 2.4% | |

| 1980 | 11,341 | 17.6% | |

| 1990 | 8,526 | −24.8% | |

| 2000 | 9,189 | 7.8% | |

| 2010 | 7,335 | −20.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 6,666 | [4] | −9.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

As of the census[32] of 2000, there were 9,189 people, 3,016 households, and 2,078 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,396.0 people per square mile (1,309.2/km2). There were 3,226 housing units at an average density of 1,192.2 per square mile (459.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 74.79% African American, 23.22% White, 0.16% Native American, 0.19% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.13% from other races, and 1.49% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.12% of the population.

There were 3,016 households, out of which 36.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.4% were married couples living together, 30.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.1% were non-families. 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.82 and the average family size was 3.49.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 37.6% under the age of 18, 10.9% from 18 to 24, 23.3% from 25 to 44, 17.6% from 45 to 64, and 10.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $17,142, and the median income for a family was $20,100. Males had a median income of $22,346 versus $14,679 for females. The per capita income for the city was $8,324. About 35.7% of families and 43.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 59.2% of those under age 18 and 25.2% of those age 65 or over.

Education[]

Madison Parish School Board operates public schools.[33]

- - grades 9-12

- Madison Middle School (grades 7 and 8)

- Wright Elementary School (grades 4-6)

- Tallulah Elementary School (grades PreK-3)

Louisiana Technical College operates a Tallulah campus.

Notable people[]

- Clifford Cleveland Brooks, planter in St. Joseph, represented Madison Parish in the Louisiana State Senate from 1924 to 1932.[34]

- Buddy Caldwell, former Attorney General of Louisiana since 2008; former Madison, East Carroll, and Tensas parish district attorney

- James Haynes, NFL player

- John Littleton, born in Tallulah (1930) and died in France (1998), opera and gospel singer.

- Jimmy "Cooch Eye" Jones, former National Basketball Association (NBA) player with the Baltimore Bullets

- Paul Jorgensen, professional boxer

- , state representative from 1952 to 1968 and interim judge, 1992-1993[35]

- John Little, professional football player

- Joe Osborn, musician

- James E. Paxton, district attorney for Madison, East Carroll, and Tensas parishes; native of Madison Parish; resides in St. Joseph in Tensas Parish[36]

- Andrew Jackson Sevier, Sheriff of Madison Parish from 1904 to 1941.

- James Silas, professional basketball player.

- Jefferson B. Snyder, district attorney of Madison Parish from 1904 to 1948.

- Madam C. J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana. She was a businesswoman who became a self-made millionaire from health care products she developed and sold for African Americans.

- Felicia Toney Williams, attorney, became the first woman elected to the Louisiana Second Circuit Court of Appeal in 1992. She was sworn in on October 4, 2018 as the north Louisiana appellate court's first female chief judge.[37]

- Zelma Wyche, political activist, first African-American police chief, and elected mayor of Tallulah, sometimes called "Mr. Civil Rights of Louisiana".

See also[]

Representation in other media[]

- Donna Jo Napoli, Alligator Bayou (2009), young adult historical novel about the 1899 lynchings of Italians in Tallulah, published by Wendy Lamb Books.

Further reading[]

- “Tallulah’s Shame", Harper’s Magazine, July 1899

- Patrizia Salvetti, Corda e Sapone (in Italian) (2012); Rope and Soap: Lynchings of Italians in the United States, English translation, New York, NY : Bordighera Press, [2017]

References[]

- ^ "City Council". City of Tallulah. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Bonne Bolden (September 1, 2018). "UPDATE: Tallulah mayor dead after medical procedure". . Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ "Tallulah, Louisiana". quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963; ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 155

- ^ Jump up to: a b [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ken Scambray, " 'Corda e Sapone' (Rope and Soap): how the Italians were lynched in the USA", L'Italo-Americano, 13 December 2012; accessed 14 May 2018

- ^ Richard P. Sevier, Madison Parish, Arcadia Publishing, 2003, p. 61

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Delta Airlines Beginnings". Louisiana Delta 65. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Richard P. Sevier (2003), Madison Parish, p. 55

- ^ R.P. Sevier (2003), Madison Parish, p. 64

- ^ Bloom's Arcade profile, Historical Places website; accessed June 30, 2014.

- ^ John Lewis and Archie E. Allen, "Black Voter Registration in the South", Notre Dame Law Review, Volume 48|Issue 1; October 1972

- ^ Charles L. Sanders (January 1970). Black Lawman in KKK Territory. Ebony Magazine. pp. 57–64. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martin Waldron (October 5, 1969). "Black police chief finds white support not easy to obtain". New York Times (Eugene Register-Guard). Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Thomas A. Johnson, "Louisiana Negroes Seek Power", New York Times, 29 September 1971; accessed 20 March 2018

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Katy Reckdahl (2 August 2004). "Taking Back Tallulah". The Advocate. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chicago Mill and Lumber Company/ "A Death In The Delta: Tallulah’s Tragic ", The Frontline blog, 11 January 2017

- ^ Jump up to: a b National Register Staff (August 1998). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Hermione". National Park Service. Retrieved September 4, 2018. (comprising 1988 registration form #88002652), With seven photos from 1988 and 13 photos from 1998.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Louisiana Honors Its African-American Heritage, state tourism website

- ^ National Weather Service. (2010). NWS Jackson, MS - April 24, 2012 violent long track tornado. Retrieved from https://www.weather.gov/jan/2010_04_24_main_tor_madison_parish_oktibbeha

- ^ National Weather Service. (2010). 20100424's storm report (1200 UTC - 1159 UTC). Retrieved from https://www.spc.noaa.gov/exper/archive/event.php?date=20100424

- ^ "Madison Parish LTCW", LaSalle Corrections website

- ^ "Our Locations", LaSalle Corrections website

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Sevier Family of Madison Parish, Louisiana". rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Tallulah, LA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Tallulah Vicksburg AP, LA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ District, Madison Parish School. "Madison Parish School District - Schools". www.madisonpsb.org. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ , History of Louisiana, Vol. 2 (Chicago and New York City: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1925, p. 71)

- ^ "Edgar H. Lancaster obituary". The Monroe News-Star. October 15, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "James E. Paxton". sixthda.com. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "Chief Judge Felicia Toney Williams". la2nd.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tallulah, Louisiana. |

- City of Tallulah

- Tallulah Progress Community Progress Site for Tallulah, LA

- Cities in Louisiana

- Cities in Madison Parish, Louisiana

- Parish seats in Louisiana

- Cities in North Louisiana