Waukegan, Illinois

Waukegan, Illinois | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Waukegan | |

From top to bottom: Waukegan skyline, downtown Waukegan, Genesee Theatre | |

Flag  Seal  Logo | |

| Nickname(s): WaukTown, Green Town, Talk Town | |

| Motto(s): "An Illinois Arts-Friendly Community" | |

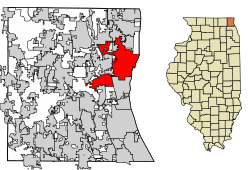

Location of Waukegan in Lake County, Illinois. | |

Waukegan, Illinois Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 42°22′13″N 87°52′16″W / 42.37028°N 87.87111°WCoordinates: 42°22′13″N 87°52′16″W / 42.37028°N 87.87111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Counties | Lake |

| Founded | 1829 |

| Incorporated (town) | March 31, 1849 |

| Incorporated (city) | February 23, 1859 |

| Named for | Potawatomi: wakaigin (Fortress or Little Fort) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Ann Taylor |

| Area | |

| • City | 24.50 sq mi (63.46 km2) |

| • Land | 24.26 sq mi (62.84 km2) |

| • Water | 0.24 sq mi (0.63 km2) 0.99% |

| Elevation | 715 ft (218 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 89,321[1] |

| • Rank | 10th largest in Illinois[2] 367th largest in U.S.[3] |

| • Density | 3,547.88/sq mi (1,369.84/km2) |

| • Metro | 9,472,676 |

| Demonym(s) | Waukeganite |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 60079, 60085, 60087 |

| Area code(s) | 847 & 224 |

| FIPS code | 17-79293 |

| U.S. Routes | |

| Major State Routes | |

| Waterways | Waukegan River |

| Airports | Waukegan National Airport |

| Website | www |

Waukegan (/wɔːˈkiːɡən/) is the largest city in, and the county seat of Lake County, Illinois, United States. Located approximately halfway between Downtown Chicago and Downtown Milwaukee, Waukegan is situated within the Chicago Metropolitan Area and classified as a satellite city of Chicago. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 89,321, making it the tenth most populous city in Illinois. Waukegan is a predominantly working-class community, with a moderately sized middle-class population.

History[]

Founding and 19th century[]

The site of present-day Waukegan was recorded as Rivière du Vieux Fort ("Old Fort River") and Wakaygagh on a 1778 map by Thomas Hutchins. By the 1820s, the French name had become "Small Fort River" in English, and the settlement was known as "Little Fort". The name "Waukegance" and then "Waukegan" (meaning "little fort"; cf. Potawatomi wakaigin "fort" or "fortress") was created by John H. Kinzie and Solomon Juneau, and the new name was adopted on March 31, 1849.[7][8]

Waukegan had an abolitionist community dating to these early days. In 1853, residents commemorated the anniversary of emancipation of slaves in the British Empire with a meeting.[9] Waukegan arguably has the distinction of being the only place where Abraham Lincoln failed to finish a speech; when he campaigned in the town in 1860, a fire alarm rang, and the man soon-to-be president had his words interrupted.[10]

During the middle of the 19th century, Waukegan was becoming an important industrial hub. Industries included: ship and wagon building, flour milling, sheep raising, pork packing, and dairying. William Besley's Waukegan Brewing Company was one of the most successful of these businesses, being able to sell beyond America.[11] The construction of the Chicago and Milwaukee Railway through Waukegan by 1855 stimulated the growth and rapid transformation and development of the city's industry, so much that nearly one thousand ships were visiting Waukegan harbor every year.[11] During the 1860s, a substantial German population began to grow inside the city[11]

Waukegan's development began in many ways with the arrival of industries such as United States Sugar Refinery, which opened in 1890,[12] Washburn & Moen, a barbed-wire manufacturer that prompted both labor migration and land speculation beginning in 1891,[13] U.S. Starch Works, and Thomas Brass and Iron Works. Immigrants followed, mostly hailing from southeastern Europe and Scandinavia, with especially large groups from Sweden, Finland, and Lithuania.[14][15] The town also became home to a considerable Armenian population.[16][17] One member of this community, Monoog Curezhin, even became embroiled in an aborted plot to assassinate Sultan Abdul Hamid II, reviled for his involvement in massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Curezhin lost two fingers on his right hand while testing explosives for this purpose in Waukegan in 1904.[18]

20th and 21st century[]

1900 to 1990[]

By the 1920s and 1930s, African-Americans began to migrate to the city, mostly from the south.[19] The town was no stranger to racial strife. In June 1920, an African-American boy allegedly hit the car of an off-duty sailor from nearby Great Lakes Naval Base with a rock, and hundreds of white sailors gathered at Sherman House, a hotel reserved for African-Americans. Although newspaper reports and rumors suggested that the officer's wife was hit with glass from the broken windshield, subsequent reports revealed that the officer was not married.[20] The sailors cried "lynch 'em," but were successfully kept back by the intervention of the police.[21] Marines and sailors renewed their attack on the hotel several days later. The Sherman's residents fled for their lives as the military members carried torches, gasoline, and the American flag.[22] The Waukegan police once again turned them away, but not before firing and wounding two members of the crowd.[23] The police were not always so willing to protect Waukegan's citizens. The chief of police and the state's attorney in the 1920s, for example, were avowed members of the Ku Klux Klan, facts that came to light when a wrongfully convicted African-American war veteran was released from prison on appeal after 25 years.[24][25] Labor unrest also occurred regularly. In 1919, a strike at the US Steel and Wire Company – which had acquired Washburn & Moen – led to a call for intervention from the state militia.[26][27]

Noted organized crime boss Johnny Torrio served time in Waukegan's Lake County jail in 1925. He installed bulletproof covers on the windows of his cell at his own expense for fear of assassination attempts.[28]

The city has retained a distinct industrial character in contrast to many of the residential suburbs along Chicago's North Shore.[15] The financial disparity created by the disappearance of manufacturing from the city in part contributed to the Waukegan riot of 1966. Central to this event and the remainder of Waukegan's 20th century history was Robert Sabonjian, who served as mayor for 24 years, and earned the nickname the "Mayor Daley of Waukegan" for his personal and sometimes controversial style of politics.[29]

Geography[]

Waukegan is located at 42°22′13″N 87°52′16″W / 42.37028°N 87.87111°W (42.3703140, −87.8711404).[5] Waukegan is on the shore of Lake Michigan, about 11 miles (18 km) south of the border with Wisconsin and 37 miles (60 km) north of downtown Chicago, at an elevation of about 650 feet (200 m) above sea level.[5]

According to the 2010 census, Waukegan has a total area of 24.50 square miles (63.45 km2), of which 24.26 square miles (62.83 km2) are land and 0.24 square miles (0.62 km2), or 0.99%, are water.[30]

Climate[]

Waukegan is located within the humid continental climate zone (Köppen: Dfa) with warm to hot (and often humid) summers, and cold and snowy winters. The record high temperature is 108 °F (42 °C), which was set in July 1934, while the record low is −27 °F (−33 °C), set in January 1985.[31] Waukegan's proximity to Lake Michigan helps cool the city throughout the year.

| hideClimate data for Waukegan, IL (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

71 (22) |

83 (28) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

90 (32) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 48 (9) |

51 (11) |

67 (19) |

80 (27) |

86 (30) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

90 (32) |

81 (27) |

67 (19) |

53 (12) |

96 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 29.9 (−1.2) |

34.1 (1.2) |

44.0 (6.7) |

55.9 (13.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

77.0 (25.0) |

81.4 (27.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

73.0 (22.8) |

61.0 (16.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

34.2 (1.2) |

57.0 (13.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.5 (−5.3) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

35.9 (2.2) |

46.9 (8.3) |

56.8 (13.8) |

67.0 (19.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

71.3 (21.8) |

63.4 (17.4) |

51.6 (10.9) |

39.8 (4.3) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

48.4 (9.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.1 (−9.4) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

37.8 (3.2) |

47.0 (8.3) |

57.1 (13.9) |

63.2 (17.3) |

62.7 (17.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

42.3 (5.7) |

32.1 (0.1) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

39.9 (4.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−3 (−19) |

8 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

32 (0) |

42 (6) |

49 (9) |

49 (9) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−2 (−19) |

−12 (−24) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−24 (−31) |

−12 (−24) |

8 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

27 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

−5 (−21) |

−23 (−31) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.69 (43) |

1.31 (33) |

2.25 (57) |

3.37 (86) |

3.37 (86) |

3.79 (96) |

3.29 (84) |

3.51 (89) |

3.43 (87) |

2.51 (64) |

2.43 (62) |

1.82 (46) |

32.31 (821) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.8 (27) |

8.4 (21) |

6.4 (16) |

1.4 (3.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.0 (5.1) |

8.4 (21) |

36.4 (92) |

| Source: [32] | |||||||||||||

Superfund sites[]

Waukegan contains three Superfund sites of hazardous substances that are on the National Priorities List.

In 1975, PCBs were discovered in Waukegan Harbor sediments. Investigation revealed that during manufacturing activities at Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC), hydraulic fluids containing PCBs had been discharged through floor drains at the OMC plant, directly to Waukegan Harbor and into ditches discharging into Lake Michigan.[33] The OMC plants were subsequently added to the National Priorities List, and was designated as one of 43 Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Cleanup of the site began in 1990, with OMC providing $20–25 million in funding. During the OMC cleanup, additional soil contaminants were found at the location of the former Waukegan Manufactured Gas and Coke company. Soil removal was completed at the Coke site in 2005, and cleanup of that soil will continue for several years.

The Johns Manville site is located one mile (1.6 km) north[34] of the OMC site. In 1988, asbestos contamination found in groundwater and air prompted listing on the National Priorities List and subsequent cleanup. In 1991, the soil cover of the asbestos was completed. However, additional asbestos contamination was found outside the Johns-Manville property which will require further cleanup.[35][36]

The Yeoman Creek Landfill[37] is a Superfund site located 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of the Johns Manville site. The site operated as a landfill from 1959 to 1969. In 1970, it was discovered that the lack of a bottom liner in the landfill had allowed leachate to enter groundwater, contaminating the water with volatile organic compounds and PCBs, and releasing gases that presented an explosion hazard. All major cleanup construction activities were completed in 2005, and monitoring of local water and air continues.[38]

The book Lake Effect by Nancy Nichols gives an account of the effects of PCBs on Waukegan residents. Johns Manville is a site that was cited due to its high concentration of PCBs and Asbestos.

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 3,433 | — | |

| 1870 | 4,507 | 31.3% | |

| 1880 | 4,012 | −11.0% | |

| 1890 | 4,915 | 22.5% | |

| 1900 | 9,426 | 91.8% | |

| 1910 | 16,069 | 70.5% | |

| 1920 | 19,226 | 19.6% | |

| 1930 | 33,499 | 74.2% | |

| 1940 | 34,241 | 2.2% | |

| 1950 | 46,698 | 36.4% | |

| 1960 | 61,784 | 32.3% | |

| 1970 | 65,134 | 5.4% | |

| 1980 | 67,653 | 3.9% | |

| 1990 | 69,392 | 2.6% | |

| 2000 | 89,426 | 28.9% | |

| 2010 | 89,078 | −0.4% | |

| 2020 | 89,321 | 0.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 89,078 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the town was 46.6% White (21.7% non-Hispanic White), 19.2% African-American, 4.3% Asian, 1.2% Native American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 24.6% some other race, and 4.1% of two or more races. 53.4% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race). Majority of residents of Latin American descent in Waukegan are of Mexican descent, Waukegan also has one of the highest Honduran population in Illinois, as well as many Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central American descendants. 5.3% were of German ancestry.[40]

As of the census[40] of 2000, there were 87,901 people, 27,787 households, and 19,450 families living in the city. The population density was 1,475.0/km2 (3,762.8/mi2). There were 29,243 housing units at an average density of 490.7/km2 (1,270.8/mi2). The racial makeup of the city was 30.92% White, 19.21% African American, 0.54% Native American, 3.58% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 22.96% from other races, and 3.50% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 44.82% of the population.

There were 27,787 households, out of which 40.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.5% were married couples living together, 14.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.0% were non-families. 24.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.09 and the average family size was 3.68.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 30.2% under the age of 18, 12.1% from 18 to 24, 33.4% from 25 to 44, 16.4% from 45 to 64, and 7.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $42,335, and the median income for a family was $47,341. Males had a median income of $30,556 versus $25,632 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,368. About 24% of families and 24.7% of the population were below the poverty line.

Religion[]

Of the 54.4% of the population that identify as religious, the most populous group is Catholic, at 31.0%. Additional percentages are 3.2% Lutheran, 1.9% Baptist, 1.6% Presbyterian, 1.5% Methodist, and approximately 11% other Christian denominations. Other faiths include 2.7% Jewish, and 1.4% Islamic.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago operates Catholic churches. On July 1, 2020, St. Anastasia Parish and St. Dismas Parish will merge, with the former having the parish school and the latter having the parish church.[41]

Government[]

The City of Waukegan is run on a mayor–council government. The city government consists of a single elected mayor and city clerk, with a city council composed of nine aldermen. The alderman are elected to represent the nine wards that the city is made up of. Any new member is sworn on the first Monday in May of their respective election year, as it coincides with the first city council meeting of the month.

City Council[]

The current members of the city council[42] with their respective political affiliation[43] are as follow:

- 1st Ward – Dr. Sylvia Sims Bolton; Democratic Party

- 2nd Ward – Patrick D. Seger; Democratic Party

- 3rd Ward – Greg "Coach Mo" Moisio; Democratic Party

- 4th Ward – Dr. Roudell Kirkwood; Democratic Party

- 5th Ward – Edith L. Newsome; Republican Party

- 6th Ward – Keith E. Turner; Democratic Party

- 7th Ward – Felix L. Rivera; Independent

- 8th Ward – Dr. Lynn M. Florian; Democratic Party

- 9th Ward – Thomas Hayes; Unknown

Members of the city council serve for four years, and are all elected on the same election year. The last election was in April 2019, with the next one scheduled for April 2023. The 9th Ward seat was replaced by Thomas Hayes, appointed by Ann Taylor as she gave up her seat to be inaugurated as mayor.[44]

Mayor[]

The current mayor of Waukegan is Ann Taylor, the city's first female mayor. She was elected in April 2021, defeating incumbent Sam Cunningham, the city's first African American mayor.[45]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Ann Taylor | 3,643 | 55.72 | |

| Democratic | Sam Cunningham | 2,895 | 44.28 | |

| Total votes | 6,538 | 100.00 | ||

Since at least 1996, no mayor has been elected for more than a single term.[46]

Economy[]

Top employers[]

According to Waukegan's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[47] the top employers in the city were:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lake County | 1,718 |

| 2 | Southwire Co. | 1,500 |

| 3 | Medline Industries Inc. | 850 |

| 4 | Vista Medical East Center | 838 |

| 5 | Lake Behavioral Hospital | 800 |

| 6 | Jewel-Osco | 515 |

| 7 | Waukegan Community Unit School District 60 | 500 |

| 8 | Bel Resources | 450 |

| 9 | Kiley Developmental Center | 423 |

| 10 | Yaskawa America, Inc. | 400 |

Revitalization[]

The city has plans for redevelopment of the lakefront.[48] The lakefront and harbor plan calls for most industrial activity to be removed, except for the Midwest Generation power plant and North Shore wastewater treatment facilities. The existing industry would be replaced by residential and recreational space. The city also set up several tax increment financing zones which have been successful in attracting new developers. The first step in the revitalization effort, the opening of the Genesee Theatre, has been completed, many new restaurants have opened, buildings have been renovated, and the City of Waukegan has made substantial investments in the pedestrian areas and other infrastructure.

The city had an annual "Scoop the Loop" summer festival of cruising since 1998, which since 2010 became a monthly event during the summer. The current incarnation is known as "Scoop Unplugged".[49]

Tourism[]

This section does not cite any sources. (April 2012) |

Popular events[]

- ArtWauk is an art event that happens every third Saturday of the month in downtown Waukegan. ArtWauk features paintings, sculptures, films, dance, theater, comedy, music, performance art, food, and pedicabs all in the Waukegan Arts District in downtown Waukegan.[50]

- Chicago Latino Film Festival

- The Fiestas Patrias Parade and Festival in downtown Waukegan highlights and celebrates the independence of the many Hispanic countries that are represented in Waukegan, including Mexico, Belize, Honduras, etc.

- HolidayWAUK (HolidayWalk) is downtown Waukegan's holiday festival.

Popular tourist destinations[]

- Downtown Waukegan

- Downtown Waukegan is the urban center of Lake County. Many restaurants, bars, shops, the Waukegan Public Library, the College of Lake County, the Lake County Courthouse (including the William D. Block Memorial Law Library), and much more call Downtown Waukegan their home.

- Genesee Theatre

- Waukegan Municipal Beach

- Waukegan Harbor Light

- Green Town on the Rocks outdoor music venue

- Ray Bradbury sites

- Waukegan History Museum

- Bowen Park

- Jack Benny Center

- Lake County Sports Center

Notable people[]

Jack Benny[]

Waukegan is the hometown of comedian Jack Benny (1894–1974), one of the 20th century's most notable and enduring entertainers, but although he claimed for decades on his radio and television shows to have been born there, he was actually born at Mercy Hospital in Chicago. Benny's affection for the town in which he grew up can clearly be felt by this exchange with his co-star (and wife) Mary Livingstone during a conversation they had on The Jack Benny Program on Mother's Day of 1950 while they were discussing the itinerary for his summer tour that year:

- Mary Livingstone: Aren't you going to bring your show to Waukegan?

- Jack Benny: Mary, I was born in Waukegan — how can you follow that?!.

On a 1959 episode of the television game show What's My Line?, Benny quipped to host John Charles Daly

They say that I put Waukegan on the map. But it's not true. Waukegan really put me on the map. That's a fact.[51]

Nevertheless, Benny did put Waukegan on the map for millions of his listeners (and later viewers) over the years, and the community was proud of his success. A Waukegan middle school is named in his honor (which he said was the greatest thrill he had ever experienced[52]), and a statue of him, dedicated in 2002, stands in the downtown facing the Genesee Theater, which hosted the world premiere of his film Man about Town in 1939, with Jack, Mary, Dorothy Lamour, Phil Harris, Andy Devine, Don Wilson and Rochester (Eddie Anderson) appearing onstage.

Jack Benny's family lived in several buildings in Waukegan during the time he was growing up there, but the house at 518 Clayton Street is the only one of them that still stands. It was designated a landmark by the city on April 17, 2006.[53]

Ray Bradbury[]

The science-fiction author and novelist Ray Bradbury (1920–2012), was born in Waukegan, and though he moved with his family to the West Coast while still a child, many of his stories explicitly build on Waukegan (often called Green Town in his stories, such as Dandelion Wine) and his formative years there.[54][55] Ray Bradbury Park, located at 99 N. Park Ave. in Waukegan, is named after him.

Otto Graham[]

Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham (1921–2003) was born and raised in Waukegan and attended nearby Northwestern University on a basketball scholarship, though football soon became his main sport. Graham played quarterback for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL), taking his team to league championships every year between 1946 and 1955, winning seven of them. While most of Graham's statistical records have been surpassed in the modern era, he still holds the NFL record for career average yards gained per pass attempt, with 8.98. He also holds the record for the highest career winning percentage for an NFL starting quarterback, at 0.814. Graham is one of only two people (the other being Gene Conley) to win championships in two of the four major North American sports—1946 NBL (became NBA) and AAFC championship, plus three more AAFC and three NFL championships.

Education[]

Waukegan is served by the Waukegan Public School District 60. It serves about 17,000 students in preschool through grade twelve. Waukegan has three early childhood schools, fifteen elementary schools, five middle schools, and three high school campuses.

The multi-campus Waukegan High School serves high school students. From 1999 to 2009, the current Washington campus served as the Ninth Grade Center, while Brookside Campus served students in grades 10–12. Since then, both campus have served students in grades 9–12, who are split into numbered houses.[56]

Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, a private Catholic high school, is in Waukegan.

Immanuel Lutheran School is a Pre-K-8 grade school of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod in Waukegan.[57][58]

Government services[]

Transportation[]

Waukegan has a port district which operates the city harbor and regional airport.

- Waukegan Harbor:

- Marina provides services and facilities for recreational boaters.

- Industrial port provides access for 90–100 large shipping vessels yearly. Companies with cargo facilities at the port currently include Gold Bond Building Products (capacity for 100,000 tons of gypsum), LaFarge Corp (12 cement silos), and St Mary's Cement Co (2 cement silos).[59][60][61]

- Waukegan National Airport:

- FAA certified for general aviation traffic

- Has a U.S. Customs facility, allowing for direct international flights.

- The Lake County McClory recreational trail passes through Waukegan. It provides a non-motor route spanning from Kenosha, Wisconsin, to the North Shore, along the right of way of the former Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad.

- Metra provides service between Waukegan and downtown Chicago via the Union Pacific/North Line. Service runs daily from early morning to late evening. Pace provides public bus service throughout Waukegan and surrounding areas. Most buses run Monday thru Saturday with limited Sunday/Holiday service on two routes.

- Waukegan has three licensed taxi companies. 303 Taxi, Metro Yellow&Checker Cabs and Speedy Taxi which operate under city ordinances.

Fire department[]

The Waukegan Fire Department provides fire protection and paramedic services for city. There are five fire stations. Firefighters, lieutenants, and captains are represented by the International Association of Fire Fighters.

Historical sites[]

- Bowen Park

- Naval Station Great Lakes

- Waukegan Building

- Waukegan Public Library

Artistic references[]

- Ray Bradbury spent his childhood in Waukegan and used it as the basis for Green Town, the setting of three of his books: Dandelion Wine (1957), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and Farewell Summer (2006). In his essay "Just This Side of Byzantium" and poem "Byzantium, I come not from," Bradbury explains the relationship between Green Town and his memories of Waukegan.

- In her poem 'Twee visschers', written in Dutch by the Surinam writer Rudie van Lier two men, a white and a black are fishing together near Waukegan. They are described as the new future.

- Eleanor Taylor Bland is an author of crime fiction taking place in "Lincoln Prairie" an amalgam of Waukegan, North Chicago, and Zion.[62]

- The character Johnny Blaze from the Marvel comic book Ghost Rider is described as having been born in Waukegan.[63]

- Waukegan's Amstutz Expressway, locally known as the "Expressway to Nowhere", has been used as a shooting location for such films as Groundhog Day, The Ice Harvest, The Blues Brothers, Contagion and Batman Begins.

- The music video "In Love with a Thug" sung by Sharissa featuring R. Kelly was filmed in Waukegan predominantly on the corner of Water Street and Genesee Street.

- In 2005 Ringo Starr and the Round heads recorded a concert for an episode of Soundstage at the Genesee Theatre in Waukegan.

- In their 1979 novel Stardance, Spider & Jeanne Robinson refer to Waukegan as if it were a prototypical Earth location, as identified by gravity vs. free fall.

- The hip-hop group Atmosphere namechecks the city in live performances of the song "You."

- Tom Waits mentions Waukegan in the song "Gun Street Girl" from his album Rain Dogs (1985): "He left Waukegan at the slamming' of the door".

- The band The Ike Reilly Assassination mentions Waukegan in the song "The Ex-Americans" from the 2004 album Sparkle in the Finish.

- The band Eddie From Ohio has a song titled "HoJo's in Waukegan" on the album Actually Not.

Sister cities[]

Waukegan has one sister city:[64]

![]() Miyazaki, Japan

Miyazaki, Japan

Although there is no official sister city relationship, Waukegan is home to approximately 6,000 people from Tonatico, Mexico, according to a February 2017 article in the Washington Post. This has created ongoing ties between the two cities.[65]

References[]

- ^ "QuickFacts Waukegan city, Illinois; United States". census.gov. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "All cities, towns, villages and unincorporated places in Illinois of more than 15,000 inhabitants". Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Bureau, U. S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Waukegan (city), Illinois". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. July 8, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "City of Waukegan". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Callary, Edward. 2009. Place Names of Illinois. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, p. 368.

- ^ Chicago and North Western Railway Company (1908). A History of the Origin of the Place Names Connected with the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railways. p. 136.

- ^ "West India Emancipation". The National Era (Washington, DC). August 18, 1853.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Rita (June 29, 1947). "Waukegan has City's Din Amid Rural Scenes". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Waukegan, IL". encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Dretske, Diana (April 27, 2010). "Waukegan saw business boom in 1890". Daily Herald. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ "Wild Activity at Waukegan: the Town is Fairly Overrun with Enthusiastic Acre Speculators". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 25, 1891.

- ^ "Places". Waukegan Historical Society. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kirkpatrick, Clayton (January 31, 1951). "Waukegan: It's Working Man's Town – and How! City Glories in Smoking Stacks along Lake". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- ^ "Armenians in Waukegan – St. George Armenian Church". sites.google.com. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Mirak, Robert (1983). Torn Between Two Lands: Armenians in America, 1890 to World War I. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 79.

- ^ "Armenian Plotter is Taken: Chicagoan Admits Having Been Assigned to Kill the Sultan". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 20, 1907.

- ^ "Places". Waukegan Historical Society. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Chicago Commission on Race Relations. Racial Clashes, 1920.

- ^ "Sailors Riot in Waukegan Race Clash". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 1, 1920.

- ^ "2 Marines Shot as Sailors and Police Clash: Waukegan Site of New Race Riot". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 3, 1920.

- ^ "Sailors Renew Race Riots". New York Times. June 3, 1920.

- ^ "Crime Non-Existent, Trial 'Sham,' Court Frees Negro After 26 Years". New York Times. August 11, 1949.

- ^ Coleman, Ted (September 24, 1949). "Ku Kluxers Still Stalking 'Big Jim' After 25 Years". The Pittsburgh Courier.

- ^ "2,000 in Riot at Waukegan". The Washington Herald. September 30, 1919.

- ^ "State Militia Sent". The Daily Gate City and Constitution Democrat. September 26, 1919.

- ^ "Torrio Fortifies Jail Cell; Rumors of War". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 25, 1925.

- ^ Myers, Linner (June 9, 1985). "'Mayor Daley of Waukegan' Back to Show 'Em Who's Boss". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Illinois". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "XMACIS2". XMACIS2. National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ "Monthly Climate Normals (1981–2010) Waukegan, IL". National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ "Waukegan Harbor River Area of Concern". US EPA. August 20, 2015.

- ^ Coordinates of Johns Mannville site. Maps.google.com (January 1, 1970).

- ^ "Johns-Manville Corp". EPA. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ^ "Asbestos contaminated shore". Dunesland Preservation Society. November 2006.

- ^ "Yeoman Creek Landfill". Archived from the original on March 24, 2008.

- ^ "ILD980500102, NPL Fact Sheet – Region 5 Superfund – US EPA". epa.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Anderson, Javonte (February 7, 2020). "23 Chicago-area Roman Catholic parishes to close, merge in latest round of restructuring". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Aldermen | Waukegan, IL – Official Website". www.waukeganil.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ contact@scytl.com, scytl. "Election Night Reporting". index.html. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Sadin, Steve. "Ann Taylor declares victory in bid to become Waukegan's first female mayor in one of 345 election races in Lake County". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ "Mayor | Waukegan, IL – Official Website". www.waukeganil.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Sadin, Steve. "Ann Taylor declares victory in bid to become Waukegan's first female mayor in one of 345 election races in Lake County". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports | Waukegan, IL – Official Website". www.waukeganil.gov. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Plans for redevelopment of the lakefront. Waukeganvision.com.

- ^ "Scoop Unplugged and Oktoberfest". Waukegan Arts Council. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ^ "ArtWauk". Waukegan Main Street.

- ^ "Jack Benny—What's My Line (HQ Version)". June 21, 1959. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Wolters, Larry (October 23, 1961). "Jack Benny at Best on Waukegan Show". The Chicago Tribune: C9.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Waukegan Historical Society – Waukegan Landmarks. Accessed April 16, 2010

- ^ "Ray Bradbury". waukeganpl.org. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Keilman, John (June 7, 2012). "Waukegan's landscape, values never left Bradbury". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "District History • Page – Waukegan CUSD". wps60.org.

- ^ "Immanuel Lutheran Church and School".

- ^ "Immanuel Ev. Lutheran Church and School – Waukegan, IL". facebook.com.

- ^ seriesmain_rpt. (PDF).

- ^ "Harbor cleanup moves forward". Chicago Tribune. August 8, 2007.

- ^ "Waukegan Harbor". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ^ http://www.who-dunnit.com/authors/45/

- ^ Ghost Rider Marveldirectory.com.

- ^ "Sister Cities". Lake County, Illinois Convention & Visitors Bureau.

- ^ Partlow, Joshua; Lydersen, Kari (February 4, 2017). "Trump policies strain the ties that bind a Mexican village to small-town Illinois". Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

External links[]

![]() Media related to Waukegan, Illinois at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Waukegan, Illinois at Wikimedia Commons

- Waukegan, Illinois

- 1829 establishments in Illinois

- Chicago metropolitan area

- Cities in Illinois

- Cities in Lake County, Illinois

- County seats in Illinois

- Populated places established in 1829

- Illinois populated places on Lake Michigan