Camphor

(+)- and (−)-camphor

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,7,7-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-one

| |

| Other names

2-Bornanone; Bornan-2-one; 2-Camphanone; Formosa

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| 1907611 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.860 |

| EC Number |

|

| 83275 | |

IUPHAR/BPS

|

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Camphor |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 2717 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

Chemical formula

|

C10H16O |

| Molar mass | 152.237 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White, translucent crystals |

| Odor | Fragrant and penetrating |

| Density | 0.992 g·cm−3 |

| Melting point | 175–177 °C (347–351 °F; 448–450 K) |

| Boiling point | 209 °C (408 °F; 482 K) |

| 1.2 g·dm−3 | |

| Solubility in acetone | ~2500 g·dm−3 |

| Solubility in acetic acid | ~2000 g·dm−3 |

| Solubility in diethyl ether | ~2000 g·dm−3 |

| Solubility in chloroform | ~1000 g·dm−3 |

| Solubility in ethanol | ~1000 g·dm−3 |

| log P | 2.089 |

| Vapor pressure | 4 mmHg (at 70 °C) |

Chiral rotation ([α]D)

|

+44.1° |

Magnetic susceptibility (χ)

|

−103×10−6 cm3/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| C01EB02 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

GHS hazard statements

|

H228, H302, H332, H371 |

| P210, P240, P241, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P301+312, P304+312, P304+340, P309+311, P312, P330, P370+378, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2

2

0 |

| Flash point | 54 °C (129 °F; 327 K) |

Autoignition

temperature |

466 °C (871 °F; 739 K) |

| Explosive limits | 0.6–3.5%[3] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

1310 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[4] |

LDLo (lowest published)

|

800 mg/kg (dog, oral) 2000 mg/kg (rabbit, oral)[4] |

LCLo (lowest published)

|

400 mg/m3 (mouse, 3 hr)[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 2 mg/m3[3] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 2 mg/m3[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

200 mg/m3[3] |

| Related compounds | |

Related Ketones

|

Fenchone, Thujone |

Related compounds

|

Camphene, Pinene, Borneol, Isoborneol, Camphorsulfonic acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Camphor (/ˈkæmfər/) is a waxy, flammable, transparent solid with a strong aroma.[5] It is a terpenoid with the chemical formula C10H16O. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the related kapur tree] (Dryobalanops sp.), a tall timber tree from South East Asia. It also occurs in some other related trees in the laurel family, notably Ocotea usambarensis. Rosemary leaves (Rosmarinus officinalis) contain 0.05 to 0.5% camphor,[6] while camphorweed (Heterotheca) contains some 5%.[7] A major source of camphor in Asia is camphor basil (the parent of African blue basil). Camphor can also be synthetically produced from oil of turpentine.

The molecule has two possible enantiomers as shown in the structural diagrams. The structure on the left is the naturally occurring (+)-camphor ((1R,4R)-bornan-2-one), while its mirror image shown on the right is the (−)-camphor ((1S,4S)-bornan-2-one).

Camphor is used for its scent, as an embalming fluid, as topical medication, as a manufacturing chemical, and in religious ceremonies.

Etymology[]

The word camphor derives from the French word camphre, itself from Latin: camfora, from Arabic: كافور, romanized: kāfūr, Malay: kapur, from Sanskrit: कर्पुरम्, romanized: karpuram.[8]

Camphor has been in burnt as an offering to Hindu deities as since ancient times and is known in India as "karpoora aarathi".

In Old Malay it is known as kapur Barus, which means "the chalk of Barus". Barus was an ancient port located near modern Sibolga on the western coast of Sumatra.[9] This port traded in camphor extracted from the camphor trees (Cinnamonum camphora) that were abundant in the region. Even now Indonesians refer to aromatic naphthalene balls and moth balls as kapur Barus.

Production[]

Camphor has been produced as a forest product for centuries, condensed from the vapor given off by the roasting of wood chips cut from the relevant trees, and later by passing steam through the pulverized wood and condensing the vapors.[10] By the early 19th century most camphor tree reserves had been depleted with the remaining large stands in Japan and Taiwan with Taiwanese production greatly exceeding Japanese. Camphor was one of the primary resources extracted by Taiwan’s colonial powers as well as one of the most lucrative. First the Chinese and then the Japanese established monopolies on Taiwanese camphor. In 1868 a British naval force sailed into Anping harbor and the local British representative demanded the end of the Chinese camphor monopoly, after the local Qing representative refused the British bombarded the town and took the harbor. The "camphor regulations” negotiated between the two sides subsequently saw a brief end to the camphor monopoly.[11] When its use in the nascent chemical industries (discussed below) greatly increased the volume of demand in the late 19th century, potential for changes in supply and in price followed. In 1911 Robert Kennedy Duncan, an industrial chemist and educator, related that the Imperial Japanese government had recently (1907–1908) tried to monopolize the production of natural camphor as a forest product in Asia but that the monopoly was prevented by the development of the total synthesis alternatives,[12] which began in "purely academic and wholly uncommercial"[12] form with Gustav Komppa's first report "but it sealed the fate of the Japanese monopoly […] For no sooner was it accomplished than it excited the attention of a new army of investigators—the industrial chemists. The patent offices of the world were soon crowded with alleged commercial syntheses of camphor, and of the favored processes companies were formed to exploit them, factories resulted, and in the incredibly short time of two years after its academic synthesis artificial camphor, every whit as good as the natural product, entered the markets of the world […]."[12]: 133–134 "...And yet artificial camphor does not—and cannot—displace the natural product to an extent sufficient to ruin the camphor-growing industry. Its sole present and probable future function is to act as a permanent check to monopolization, to act as a balance-wheel to regulate prices within reasonable limits." This ongoing check on price growth was confirmed in 1942 in a monograph on DuPont's history, where William S. Dutton said, "Indispensable in the manufacture of pyroxylin plastics, natural camphor imported from Formosa and selling normally for about 50 cents a pound, reached the high price of $3.75 in 1918 [amid the global trade disruption and high explosives demand that World War I created]. The organic chemists at DuPont replied by synthesizing camphor from the turpentine of Southern pine stumps, with the result that the price of industrial camphor sold in carload lots in 1939 was between 32 cents and 35 cents a pound."[13]: 293

The background of Gustaf Komppa's synthesis was as follows. In the 19th century, it was known that nitric acid oxidizes camphor into camphoric acid. Haller and Blanc published a semisynthesis of camphor from camphoric acid. Although they demonstrated its structure, they were unable to prove it. The first complete total synthesis of camphoric acid was published by Komppa in 1903. Its inputs were diethyl oxalate and , which reacted by Claisen condensation to yield diketocamphoric acid. Methylation with methyl iodide and a complicated reduction procedure produced camphoric acid. William Perkin published another synthesis a short time later. Previously, some organic compounds (such as urea) had been synthesized in the laboratory as a proof of concept, but camphor was a scarce natural product with a worldwide demand. Komppa realized this. He began industrial production of camphor in Tainionkoski, Finland, in 1907 (with plenty of competition, as Kennedy Duncan reported).

Camphor can be produced from alpha-pinene, which is abundant in the oils of coniferous trees and can be distilled from turpentine produced as a side product of chemical pulping. With acetic acid as the solvent and with catalysis by a strong acid, alpha-pinene readily rearranges into camphene, which in turn undergoes Wagner–Meerwein rearrangement into the isobornyl cation, which is captured by acetate to give . Hydrolysis into isoborneol followed by oxidation gives racemic camphor. By contrast, camphor occurs naturally as D-camphor, the (R)-enantiomer.

Biosynthesis[]

In biosynthesis, camphor is produced from geranyl pyrophosphate, via cyclisation of linaloyl pyrophosphate to bornyl pyrophosphate, followed by hydrolysis to borneol and oxidation to camphor.

Reactions[]

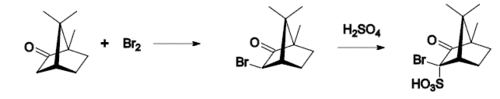

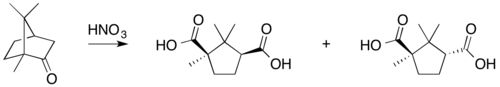

Typical camphor reactions are

- bromination,

- oxidation with nitric acid,

- conversion to .

Camphor can also be reduced to isoborneol using sodium borohydride.

In 1998, K. Chakrabarti and coworkers from the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata, prepared diamond thin film using camphor as the precursor for chemical vapor deposition.[14]

In 2007, carbon nanotubes were successfully synthesized using camphor in chemical vapor deposition process.[15]

Physical uses[]

The sublimating capability of camphor gives it several uses.

Plastics[]

The first significant manmade plastics were low-nitrogen (or "soluble") nitrocellulose (pyroxylin) plastics. In the early decades of the plastics industry, camphor was used in immense quantities[12]: 130 as the plasticizer that creates celluloid from nitrocellulose, in nitrocellulose lacquers and other plastics and lacquers.

Pest deterrent and preservative[]

Camphor is believed to be toxic to insects and is thus sometimes used as a repellent.[16] Camphor is used as an alternative to mothballs. Camphor crystals are sometimes used to prevent damage to insect collections by other small insects. It is kept in clothes used on special occasions and festivals, and also in cupboard corners as a cockroach repellent. The smoke of camphor crystal or camphor incense sticks can be used as an environmentally-friendly mosquito repellent.[17]

Recent studies have indicated that camphor essential oil can be used as an effective fumigant against red fire ants, as it affects the attacking, climbing, and feeding behavior of major and minor workers.[18]

Camphor is also used as an antimicrobial substance. In embalming, camphor oil was one of the ingredients used by ancient Egyptians for mummification.[19]

Solid camphor releases fumes that form a rust-preventative coating and is therefore stored in tool chests to protect tools against rust.[citation needed]

Perfume[]

In the ancient Arab world, camphor was a common perfume ingredient.[20] The Chinese referred to the best camphor as "dragon's brain perfume," due to its "pungent and portentous aroma" and "centuries of uncertainty over its provenance and mode of origin."[21]

Culinary uses[]

One of the earliest known recipes for ice cream dating to the Tang dynasty includes camphor as an ingredient.[22] It was used to flavor leavened bread in ancient Egypt. [23] In ancient and medieval Europe, camphor was used as an ingredient in sweets. It was used in a wide variety of both savory and sweet dishes in medieval Arabic language cookbooks, such as al-Kitab al-Ṭabikh compiled by ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq in the 10th century.[24] It also was used in sweet and savory dishes in the Ni'matnama, according to a book written in the late 15th century for the sultans of Mandu.[25]

Medicinal uses[]

Camphor is commonly applied as a topical medication as a skin cream or ointment to relieve itching from insect bites, minor skin irritation, or joint pain.[26] It is absorbed in the skin epidermis,[26] where it stimulates nerve endings sensitive to heat and cold, producing a warm sensation when vigorously applied, or a cool sensation when applied gently.[27][28][29] The action on nerve endings also induces a slight local analgesia.[30]

Camphor is also used as an aerosol, typically by steam inhalation, to inhibit coughing and relieve upper airway congestion due to the common cold.[31]

In high doses, camphor produces symptoms of irritability, disorientation, lethargy, muscle spasms, vomiting, abdominal cramps, convulsions, and seizures.[32][33][34] Lethal doses in adults are in the range 50–500 mg/kg (orally). Generally, two grams cause serious toxicity and four grams are potentially lethal.[35]

Camphor has limited use in veterinary medicine as a respiratory stimulant for horses.[36]

Camphor was used by Ladislas J. Meduna to induce seizures in schizophrenic patients.[37]

Traditional medicine[]

Camphor has been used in traditional medicine over centuries, probably most commonly as a decongestant.[27] Camphor was used in ancient Sumatra to treat sprains, swellings, and inflammation.[38] Camphor also was used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine for various purposes.[27]

Camphor was used in medieval Arab medicine for example in an account by Usāma ibn Munqiḏ the physician Ibn Buṭlān orders a woman who suffers from a coldness of the head and wears many veils because of this to procure camphor from a perfumer and to place it under her veils. She returns after having done so complaining about a hotness of the head. Ibn Buṭlān instructs her to take off her many veils. After having removed all of them but one she feels fine and her affliction is cured.[39][40]

It has also been used in India since ancient times.

Pharmacology[]

Camphor is a parasympatholytic agent which acts as a non-competitive nicotinic antagonist at nAChRs.[41][42]

Religion[]

Hindu religious ceremonies[]

Camphor is widely used in Hindu religious ceremonies. It is put on a stand called 'karpur dāni' in India. Aarti is performed after setting fire to it usually as the last step of puja.[43]

See also[]

- 1,4-Dichlorobenzene

- Citral

- Eucalyptol

- Lavender

- Vaporizer

References[]

- ^ The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co., Rahway, New Jersey, 1960

- ^ Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0096". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Camphor (synthetic)". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 4 December 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Mann JC, Hobbs JB, Banthorpe DV, Harborne JB (1994). Natural products: their chemistry and biological significance. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman Scientific & Technical. pp. 309–11. ISBN 978-0-582-06009-8.

- ^ "Rosemary". Drugs.com. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Lincoln, D.E., B.M. Lawrence. 1984. "The volatile constituents of camphorweed, Heterotheca subaxillaris". Phytochemistry 23(4):933-934

- ^ "Camphor". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Drakard, Jane (1989). "An Indian Ocean Port: Sources for the Earlier History of Barus". Archipel. 37: 53–82. doi:10.3406/arch.1989.2562.

- ^ "Camphor". britannica.com. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Cheung, Han. "Taiwan in Time: The camphor dispute". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kennedy Duncan, Robert (1911), "Camphor: An Industry Revolutionized", Some Chemical Problems of Today, Harper and Brothers, LCCN 11026192.

- ^ Dutton, William S. (1942), Du Pont: One Hundred and Forty Years, Charles Scribner's Sons, LCCN 42011897.

- ^ Chakrabarti K, Chakrabarti R, Chattopadhyay KK, Chaudhuri S, Pal AK (1998). "Nano-diamond films produced from CVD of camphor". Diam Relat Mater. 7 (6): 845–52. Bibcode:1998DRM.....7..845C. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(97)00312-9.

- ^ Kumar M, Ando Y (2007). "Carbon Nanotubes from Camphor: An Environment-Friendly Nanotechnology". J Phys Conf Ser. 61 (1): 643–6. Bibcode:2007JPhCS..61..643K. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/61/1/129.

- ^ The Housekeeper's Almanac, or, the Young Wife's Oracle! for 1840!. No. 134. New-York: Elton, 1840. Print.

- ^ Ghosh, G.K. (2000). Biopesticide and Integrated Pest Management. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-8-176-48135-9.

- ^ Fu JT, Tang L, Li WS, Wang K, Cheng DM, Zhang ZX (2015). "Carbon Nanotubes from Camphor: An Environment-Friendly Nanotechnology". J Insect Sci. 15 (1): 129. doi:10.1093/jisesa/iev112. PMC 4664941. PMID 26392574.

- ^ "Mummy-making complexity revealed". Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Groom, N. (2012). The Perfume Handbook. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-9-401-12296-2.

- ^ Donkin, R.A. (1999). Dragon's Brain Perfume: An Historical Geography of Camphor. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-10983-4.

- ^ Clarke, Chris (2004). Science of Ice Cream. Royal Society of chemistry. p. 4.

- ^ Muller, H. G. (1986). Baking and bakeries. Shire Publications. p. 7. ISBN 9780852638019.

- ^ Nasrallah, Nawal (2007). Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens: Ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq's Tenth-century Baghdadi Cookbook. Islamic History and Civilization, 70. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

- ^ Titley, Norah M. (2004). The Ni'matnama Manuscript of the Sultans of Mandu: The Sultan's Book of Delights. Routledge Studies in South Asia. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Camphor cream and ointment". Drugs.com. August 25, 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Goodman and Gilman, Pharmacological basis of therapeutics, Macmillan 1965, p. 982-983.

- ^ Green, B. G. (1990). "Sensory characteristics of camphor". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 94 (5): 662–6. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12876242. PMID 2324522.

- ^ Kotaka, T.; Kimura, S.; Kashiwayanagi, M.; Iwamoto, J. (2014). "Camphor induces cold and warm sensations with increases in skin and muscle blood flow in human". Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 37 (12): 1913–8. doi:10.1248/bpb.b14-00442. PMID 25451841.

- ^ Bonica's Management of Pain (4th ed.). Philadelphia, Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer - Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. p. 29. ISBN 9780781768276.

- ^ "Camphor". Drugs.com. November 18, 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Camphor overdose". MedlinePlus, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. January 12, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Martin D, Valdez J, Boren J, Mayersohn M (Oct 2004). "Dermal absorption of camphor, menthol, and methyl salicylate in humans". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 44 (10): 1151–7. doi:10.1177/0091270004268409. PMID 15342616. S2CID 38504197.

- ^ Uc A, Bishop WP, Sanders KD (Jun 2000). "Camphor hepatotoxicity". Southern Medical Journal. 93 (6): 596–8. doi:10.1097/00007611-200006000-00011. PMID 10881777.

- ^ "Poisons Information Monograph: Camphor". International Programme on Chemical Safety.

- ^ "Camphor injection (Canada)". Drugs.com. February 6, 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Bangen, Hans: Geschichte der medikamentösen Therapie der Schizophrenie. Berlin 1992, Page 51-55 ISBN 3-927408-82-4

- ^ Miller, Charles. History of Sumatra : An account of Sumatra. p. 121.

- ^ بن منقذ, أسامة. كتاب الاعتبار (in Arabic). pp. 94–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-13.

- ^ ibn Munqidh, Usāma (1929). An Arab-Syrian Gentleman in the Period of the Crusades: Memoirs of Usāmah ibn-Munqidh (Kitāb al-Iʿtibār). Translated by Hitti, Philip K. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 215–217. OCLC 694997626.

- ^ Park, T. J.; Seo, H. K.; Kang, B. J.; Kim, K. T. (2001). "Noncompetitive inhibition by camphor of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors". Biochemical Pharmacology. 61 (7): 787–93. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00547-0. PMID 11274963.

- ^ Park, Tae-Ju; Seo, Hyuck-Kyo; Kang, Byung-Jo; Kim, Kyong-Tai (2001). "Noncompetitive inhibition by camphor of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors". Biochemical Pharmacology. 61 (7): 787–793. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00547-0. PMID 11274963.

- ^ Bahadur, Om Lata (1996). The book of Hindu festivals and ceremonies (3rd ed.). New Delhi: UBS Publishers Distributors ltd. pp. 172–3. ISBN 978-81-86112-23-6.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camphor. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Camphors". |

- INCHEM at IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety)

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Camphor at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Pyrotechnic chemicals

- Cooling flavors

- Perfume ingredients

- Ketones

- Monoterpenes

- Ayurvedic medicaments

- Spices

- Non-timber forest products

- Cyclopentanes