Emirate of Bukhara

Emirate of Bukhara امارت بخارا Amārat-e Bokhārā | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1785–1920 | |||||||||

Flag | |||||||||

The Emirate of Bukhara under Russian rule | |||||||||

| Status | Semi-independent state (under Russian protection 1873–1917) | ||||||||

| Capital | Bukhara | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam, Shia Islam, Sufism (Naqshbandi), Zoroastrianism, Judaism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||

• 1785–1800 | Mir Masum Shah Murad | ||||||||

• 1911–1920 | Alim | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Manghit control | 1747 | ||||||||

• Established | 1785 | ||||||||

• Conquered by Russia | 1868 | ||||||||

• Russian protectorate | 1873 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | October 1920 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1875[4] | c. 2,478,000 | ||||||||

• 1911[5] | c. 3,000,000-3,500,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | fulus, tilla, and tenga.[6] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Emirate of Bukhara (Persian: امارت بخارا, romanized: Amārat-e Bokhārā, Chagatay: بخارا امرلیگی, romanized: Bukhārā Amirligi) was a Central Asian polity[8] that existed from 1785 to 1920 in what is now modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. It occupied the land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, known formerly as Transoxiana. Its core territory was the land along the lower Zarafshan River, and its urban centres were the ancient cities of Samarqand and the emirate's capital, Bukhara. It was contemporaneous with the Khanate of Khiva to the west, in Khwarazm, and the Khanate of Kokand to the east, in Fergana. In 1920, it ended with the establishment of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic.

History[]

The Emirate of Bukhara was officially created in 1785, upon the assumption of rulership by the Manghit emir, Shah Murad. Shahmurad, formalized the family's dynastic rule (Manghit dynasty), and the khanate became the Emirate of Bukhara.[9]

As one of the few states in Central Asia after the Mongol Empire not ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan (besides the Timurids), it staked its legitimacy on Islamic principles rather than Genghisid blood, as the ruler took the Islamic title of Emir instead of Khan. In 18th -19th centuries Khwarazm (Khiva Khanate) was ruled by the Uzbek dynasty of Kungrats.[10]

Over the course of the 18th century, the emirs had slowly gained effective control of the Khanate of Bukhara, from their position as ataliq; and by the 1740s, when the khanate was conquered by Nadir Shah of Persia, it was clear that the emirs held the real power. In 1747, after Nadir Shah's death, the ataliq Muhammad Rahim Bi murdered Abulfayz Khan and his son, ending the . From then on the emirs allowed puppet khans to rule until, following the death of Abu l-Ghazi Khan, Shah Murad assumed the throne openly.[11]

Fitzroy Maclean recounts in Eastern Approaches how Charles Stoddart and Arthur Conolly were executed by Nasrullah Khan in the context of The Great Game, and how Joseph Wolff, known as the Eccentric Missionary, escaped their fate when he came looking for them in 1845. He was wearing his full canonical costume, which caused the Emir to burst out laughing, and "Dr Wolff was eventually suffered to leave Bokhara, greatly to the surprise of the populace, who were not accustomed to such clemency."[12]

In 1868, the emirate lost a war with Imperial Russia, which had aspirations of conquest in the region. Russia annexed much of the emirate's territory, including the important city of Samarkand.[13] In 1873, the remainder became a Russian protectorate,[14] and was soon surrounded by the Governorate-General of Turkestan.

Reformists within the Emirate had found the conservative emir, Mohammed Alim Khan, unwilling to loosen his grip on power, and had turned to the Russian Bolshevik revolutionaries for military assistance. The Red Army launched an unsuccessful assault in March 1920, and then a successful one in September of the same year.[15] The Emirate of Bukhara was conquered by the Bolsheviks and replaced with the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic. Today, the territory of the defunct emirate lies mostly in Uzbekistan, with parts in Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. For a time, it had some influence in northern Afghanistan, as some of the Emirs of the Chahar Wilayat nominally accepted Bukharan suzerainity.

Family[]

The last emir's daughter worked as a broadcaster in Radio Afghanistan.[16] Shukria Raad left Afghanistan with her family three months after Soviet troops invaded the country in December 1979. With her husband, also a journalist, and two children she fled to Pakistan, and then through Germany to the United States. In 1982, she joined the VOA, and worked as a broadcaster for VOA's Dari Service, editor, host and producer.[17] Grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Mohammed Alim Khan currently reside in North Carolina and Washington, D.C., USA. In 2019, a couple of them made their first trip to Bukhara almost a century after the Emir's departure, where they were met warmly by local people.[18]

Culture[]

| History of Turkmenistan |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Related historical names of the region |

|

|

|

In the era of the Manghyt emirs in Bukhara, a large construction of madrasahs, mosques and palaces was carried out. Located along important trading routes, Bukhara enjoyed a rich cultural mixture, including Persian, Uzbek, and Jewish influences.

A local school of historians developed in the Bukhara emirate. The most famous historians were Mirza Shams Bukhari, Muhammad Yakub ibn Daniyalbiy, Muhammad Mir Olim Bukhari, Ahmad Donish, Mirza Abdalazim Sami, Mirza Salimbek. [19]

The city of Bukhara has a rich history of Persian architecture and literature, traditions that were continued into the Emirate Period. Prominent artists of the period include the poet Kiromi Bukhoroi, the calligrapher and the scholar . Throughout this period, the madrasahs of the region were renowned.

Chor Minor Madrasah, Bukhara (2006)

A bureaucrat in Bukhara, ca.1910

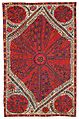

Large Medallion Suzani (textile) from Bukhara, mid-18th century?

Administrative and territorial structure[]

Administratively, the Emirate was divided into several beyliks or bekliks:

- Baljuvon

- Hisar, (now Tajikistan)

- Guzar, (now Kashkadarya Region, Uzbekistan)

- Darvaz, (c 1878, now Darvaz district, Tajikistan)

- Karategin, (now Rasht district, Tajikistan)

- Kattakurgan, (now Samarkand region, Uzbekistan)

- Kulyab, (now Khatlon region, Tajikistan)

- Karshi, (now Kashkadarya Region, Uzbekistan)

- Kerki, (now Lebap Region, Turkmenistan)

- Charjuy, (now Lebap Region, Turkmenistan)

- Nurata, (now Navoiy Region, Uzbekistan)

- Panjikent, (now Sughd province, Tajikistan)

- Rushan, (now Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous region, Tajikistan)

- Samarkand, (now Samarqand Region, Uzbekistan — part of Russia since 1868

- Shahrisabz, (c 1870, now Kashkadarya Region, Uzbekistan)

- Urgut, (now Samarqand Region, Uzbekistan)

- Falgar, (now Sughd province, Tajikistan)

Amirs/Emirs of Bukhara (1785–1920)[]

| Titular Name | Personal Name | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| Ataliq اتالیق |

Khudayar Bey خدایار بیگ |

? |

| Ataliq اتالیق |

Muhammad Hakim محمد حکیم |

?–1747 |

| Ataliq اتالیق |

Muhammad Rahim محمد رحیم |

1747–1753 |

| Amir امیر |

Muhammad Rahim محمد رحیم |

1753–1756 |

| Khan خان |

Muhammad Rahim محمد رحیم |

1756–1758 |

| Ataliq اتالیق |

Daniyal Biy دانیال بیگ |

1758–1785 |

| Amir Masum امیر معصوم |

Shahmurad شاہ مراد بن دانیال بیگ |

1785–1800 |

| Amir امیر |

Haydar bin Shahmurad حیدر تورہ بن شاہ مراد |

1800–1826 |

| Amir امیر |

Mir Hussein bin Haydar حسین بن حیدر تورہ |

1826–1827 |

| Amir امیر |

Umar bin Haydar عمر بن حیدر تورہ |

1827 |

| Amir امیر |

Nasr-Allah bin Haydar Tora نصراللہ بن حیدر تورہ |

1827–1860 |

| Amir امیر |

Muzaffar bin Nasrullah مظفر الدین بن نصراللہ |

1860–1886 |

| Amir امیر |

Abdul-Ahad bin Muzaffar al-Din عبد الأحد بن مظفر الدین |

1886–1911 |

| Amir امیر |

Muhammad Alim Khan bin Abdul-Ahad محمد عالم خان بن عبد الأحد |

1911–1920 |

| Overthrow of Emirate of Bukhara by Bukharan People's Soviet Republic. | ||

- Pink Rows Signifies progenitor chiefs serving as Tutors (Ataliqs) & Viziers to the Khans of Bukhara.

- Green Rows Signifies chiefs who took over reign of government from the and placed puppet Khans.

See also[]

- Timeline of the Uzbeks

References[]

- ^ Roy (2000), The new Central Asia: the creation of nations, p.70

- ^ "About the national delimitation in Central Asia"

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy of the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- ^ E.K. Travel from Orenburg to Bukhara. Foreword N. A. Halfin. Moscow, The main edition of the eastern literature of the publishing house "Science", 1975. (in Russian:Мейендорф Е. К. Путешествие из Оренбурга в Бухару. Предисл. Н. А. Халфина. М., Главная редакция восточной литературы издательства "Наука", 1975.)[permanent dead link]

- ^ Olufsen, Ole (1911). The emir of Bokhara and his country; journeys and studies in Bokhara. Gyldendal: Nordisk forlag. p. 282.

- ^ ANS Magazine. "The Coinage of the Mangit Dynasty of Bukhara" by Peter Donovan. Retrieved: 16 July 2017.

- ^ "VEXILLOGRAPHIA - Флаги Узбекистана".

- ^ Peter B. Golden (2011), Central Asia in World History, p.115

- ^ Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia (2000), p. 180.

- ^ Bregel, Y. The new Uzbek states: Bukhara, Khiva and Khoqand: C. 1750–1886. In N. Di Cosmo, A. Frank, & P. Golden (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age (pp. 392-411). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2009

- ^ Soucek (2000), pp. 179–180

- ^ Eastern Approaches ch 6 "Bokhara the Noble"

- ^ Soucek (2000), p. 198

- ^ Russo-Bukharan War 1868, Armed Conflict Events Database, OnWar.com

- ^ Soucek (2000), pp. 221–222

- ^ Doka, Kenneth (2014). Living With Grief. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 9781317758471.

- ^ "A Princess-Broadcaster". Voice of America. March 31, 2002. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- ^ Abidova, Sakina (October 2, 2019). "Return to the Motherland". The Mag (in Russian).

- ^ Anke fon Kyugel'gen, Legitimizatsiya sredneaziatskoy dinastii mangitov v proizvedeniyakh ikh istorikov (XVIII-XIX vv.). Almaty: Dayk press, 2004

Bibliography[]

- Soucek, Svat (2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521657044.

Literature[]

- Malikov A., The Russian conquest of the Bukharan Emirate: military and diplomatic aspects in Central Asian Survey, Volume 33, issue 2, 2014, p. 180-198

External links[]

Media related to Emirate of Bukhara at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Emirate of Bukhara at Wikimedia Commons

- Emirate of Bukhara

- 1785 establishments in Asia

- 1920 disestablishments in Russia

- Former countries in Central Asia

- Former emirates

- Former monarchies

- Former monarchies of Asia

- Former Russian protectorates

- History of Bukhara

- Mongol dynasties

- Subdivisions of the Russian Empire

- States and territories established in 1785

- States and territories disestablished in 1920

- Turkic dynasties