Fipronil

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

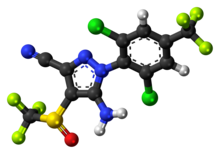

| Preferred IUPAC name

5-Amino-1-[2,6-dichloro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-4-(trifluoromethanesulfinyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carbonitrile | |

| Other names

Fipronil

Fluocyanobenpyrazole Taurus Termidor | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number

|

|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.102.312 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

show

InChI | |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula

|

C12H4Cl2F6N4OS |

| Molar mass | 437.14 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.477-1.626 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 200.5 °C (392.9 °F; 473.6 K) |

| Pharmacology | |

ATCvet code

|

QP53AX15 (WHO) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Fipronil is a broad-spectrum insecticide that belongs to the phenylpyrazole chemical family. Fipronil disrupts the insect central nervous system by blocking GABA-gated chloride channels and glutamate-gated chloride (GluCl) channels. This causes hyperexcitation of contaminated insects' nerves and muscles. Fipronil's specificity towards insects is believed to be due to its greater affinity to the GABAA receptors of insects, than to those of mammals, and to its action on GluCl channels, which do not exist in mammals.[1] As of 2017 there did not appear to be significant resistance among fleas to fipronil.[2]

Because of its effectiveness on various pests, fipronil is used as the active ingredient in flea control products for pets and home roach traps as well as field pest control for corn, golf courses, and commercial turf. Its widespread use makes its specific effects the subject of considerable attention. This includes ongoing observations on possible off-target harm to humans or ecosystems as well as the monitoring of resistance development.[3]

Use[]

Fipronil is or has been used in:

- Under the trade name Regent, it is used against major lepidopteran (moth, butterfly, etc.) and orthopteran (grasshopper, locust, etc.) pests on a wide range of field and horticultural crops and against coleopteran (beetle) larvae in soils. In 1999, 400,000 hectares were treated with Regent. It became the leading imported product in the area of rice insecticides, the second-biggest crop protection market after cotton in China.[4]

- Under the trade names Goliath and Nexa, it is employed for cockroach and ant control, including in the United States. It is also used against pests of field corn, golf courses, and commercial lawn care under the trade name Chipco Choice.[4]

- It has been used under the trade name Adonis for locust control in Madagascar and Kazakhstan.[4]

- Marketed under the names Termidor, Ultrathor, Fipforce and Taurus in Africa and Australia, fipronil effectively controls termite pests, and was shown to be effective in field trials in these countries.[4]

- Termidor has been approved for use against the Rasberry crazy ant in the Houston, Texas, area, under a special "crisis exemption" from the Texas Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency. The chemical is only approved for use in Texas counties experiencing "confirmed infestations" of the newly discovered ant species.[5] Use of Termidor is restricted to certified pest control operators in the following states: Alaska, Connecticut, Nebraska, South Carolina, Massachusetts, Indiana, New York, and Washington.[citation needed]

- In Australia, it is marketed under numerous trade names, including Combat Ant-Rid, Anthem, Clearout, Fipforce, Radiate and Termidor, and as generic fipronil

- In the UK, provisional approval for five years has been granted for fipronil use as a public hygiene insecticide.[4]

- Fipronil is the main active ingredient of Frontline TopSpot, Fiproguard, Flevox, and PetArmor (used along with S-methoprene in the 'Plus' versions of these products) in the USA and Frontline Tri-Act for Dogs, Plus (Dog), Plus (Cat), Spot-On (Dog) and Spot-On (Cat) in the UK;[6] these treatments are used in fighting tick and flea infestations in dogs and cats.

- In New Zealand, fipronil was used in trials to control wasps (Vespula spp.), which are a threat to indigenous biodiversity.[7] It is now being used by the Department of Conservation to attempt local eradication of wasps,[8][9][10] and is being recommended for control of the invasive Argentine ant.[11]

Effects[]

Toxicity[]

Fipronil is classed as a WHO Class II moderately hazardous pesticide, and has a rat acute oral LD50 of 97 mg/kg.

It has moderate acute toxicity by the oral and inhalation routes in rats. Dermal absorption in rats is less than 1% after 24 h and toxicity is considered to be low. It has been found to be very toxic to rabbits.

The photodegradate MB46513 or desulfinylfipronil, appears to have a higher acute toxicity to mammals than fipronil itself by a factor of about 10.[12]

Symptoms of acute toxicity via ingestion includes sweating, nausea, vomiting, headache, abdominal pain, dizziness, agitation, weakness, and tonic-clonic seizures. Clinical signs of exposure to fipronil are generally reversible and resolve spontaneously. As of 2011, no data were available regarding the chronic effects of fipronil on humans. The United States Environmental Protection Agency has classified fipronil as a group C (possible human) carcinogen based on an increase in thyroid follicular cell tumors in both sexes of the rat. However, as of 2011, no human data are available regarding the carcinogenic effects of fipronil.[13]

Two Frontline TopSpot products were determined by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to pose no significant exposure risks to workers applying the product. However, concerns were raised about human exposure to Frontline spray treatment in 1996, leading to a denial of registration for the spray product. Commercial pet groomers and veterinary physicians were considered to be at risk from chronic exposure via inhalation and dermal absorption during the application of the spray, assuming they may have to treat up to 20 large dogs per day.[4] Fipronil is not volatile, so the likelihood of humans being exposed to this compound in the air is low.[13]

In contrast to neonicotinoids such as acetamiprid, clothianidin, imidacloprid, and thiamethoxam, which are absorbed through the skin to some extent, fipronil is not absorbed substantially through the skin.[14]

Detection in body fluids[]

Fipronil may be quantitated in plasma by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalised patients or to provide evidence in a medicolegal death investigation.[15]

Ecological toxicity[]

Fipronil is highly toxic for crustaceans, insects (including bees and termites) and zooplankton, as well as rabbits, the fringe-toed lizard, and certain groups of gallinaceous birds. It appears to reduce the longevity and fecundity of female braconid parasitoids. It is also highly toxic to many fish, though its toxicity varies with species. Conversely, the substance is relatively innocuous to passerines, wildfowl, and earthworms.

Its half-life in soil is four months to one year, but much less on soil surface because it is more sensitive to light (photolysis) than water (hydrolysis).[16]

Few studies of effects on wildlife have been conducted, but studies of the nontarget impact from emergency applications of fipronil as barrier sprays for locust control in Madagascar showed adverse impacts of fipronil on termites, which appear to be very severe and long-lived.[17] Also, adverse effects were indicated in the short term on several other invertebrate groups, one species of lizard (Trachylepis elegans), and several species of birds (including the Madagascar bee-eater).

Nontarget effects on some insects (predatory and detritivorous beetles, some parasitic wasps and bees) were also found in field trials of fipronil for desert locust control in Mauritania, and very low doses (0.6-2.0 g a.i./ha) used against grasshoppers in Niger caused impacts on nontarget insects comparable to those found with other insecticides used in grasshopper control. The implications of this for other wildlife and ecology of the habitat remain unknown, but appear unlikely to be severe.[4] Unfortunately, this lack of severity was not observed in bee species in South America. Fipronil is also used in Brazil and studies on the stingless bee Scaptotrigona postica have shown adverse reactions to the pesticide, including seizures, paralysis, and death with a lethal dose of .54 ng a.i./bee and a lethal concentration of .24 ng a.i./μl diet. These values are highly toxic in Scaptotrigona postica and bees in general.[18] Toxic baiting with fipronil has been shown to be effective in locally eliminating German wasps. All colonies within foraging range were completely eliminated within one week.[19][20][7]

In May 2003, the French Directorate-General of Food at the Ministry of Agriculture determined that a case of mass bee mortality observed in southern France was related to acute fipronil toxicity. Toxicity was linked to defective seed treatment, which generated dust. In February 2003, the ministry decided to temporarily suspend the sale of BASF crop protection products containing fipronil in France.[21] The seed treatment involved has since been banned.[citation needed]

Notable results from wildlife studies include:

- Fipronil is highly toxic to fish and aquatic invertebrates. Its tendency to bind to sediments and its low water solubility may reduce the potential hazard to aquatic wildlife.[22]

- Fipronil is toxic to bees and should not be applied to vegetation when bees are foraging.[22]

- Based on ecological effects, fipronil is highly toxic to upland game birds on an acute oral basis and very highly toxic on a subacute dietary basis, but is practically nontoxic to waterfowl on both acute and subacute bases.[23]

- Chronic (avian reproduction) studies show no effects at the highest levels tested in mallards (NOEC) = 1000 ppm) or quail (NOEC = 10 ppm). The metabolite MB 46136 is more toxic than the parent to avian species tested (very highly toxic to upland game birds and moderately toxic to waterfowl on an acute oral basis).[23]

- Fipronil is very highly toxic to bluegill sunfish and highly toxic to rainbow trout on an acute basis.[23]

- An early-lifestage toxicity study in rainbow trout found that fipronil affects larval growth with a NOEC of 0.0066 ppm and an LOEC of 0.015 ppm. The metabolite MB 46136 is more toxic than the parent to freshwater fish (6.3 times more toxic to rainbow trout and 3.3 times more toxic to bluegill sunfish). Based on an acute daphnia study using fipronil and three supplemental studies using its metabolites, fipronil is characterized as highly toxic to aquatic invertebrates.[23]

- An invertebrate lifecycle daphnia study showed that fipronil affects length in daphnids at concentrations greater than 9.8 ppb.[23]

- A lifecycle study in mysids shows fipronil affects reproduction, survival, and growth of mysids at concentrations less than 5 ppt.[23]

- Acute studies of estuarine animals using oysters, mysids, and sheepshead minnows show that fipronil is highly acutely toxic to oysters and sheepshead minnows, and very highly toxic to mysids. Metabolites MB 46136 and MB 45950 are more toxic than the parent to freshwater invertebrates (MB 46136 is 6.6 times more toxic and MB 45950 is 1.9 times more toxic to freshwater invertebrates).[23]

Colony collapse disorder[]

Fipronil is one of the main chemical causes blamed for the spread of colony collapse disorder among bees[citation needed]. It has been found by the Minutes-Association for Technical Coordination Fund in France that even at very low nonlethal doses for bees, the pesticide still impairs their ability to locate their hive, resulting in large numbers of forager bees lost with every pollen-finding expedition.[24] A synergistic toxic effect of fipronil with the fungal pathogen Nosema ceranae was recently reported.[25] The functional basis for this toxic effect is now understood: the synergy between fipronil and the pathogenic fungus induces changes in male bee physiology leading to infertility.[26] A 2013 report by the European Food Safety Authority identified fipronil as "a high acute risk to honeybees when used as a seed treatment for maize" and on July 16, 2013 the EU voted to ban the use of fipronil on maize and sunflowers within the EU. The ban took effect at the end of 2013.[27][28]

Pharmacodynamics[]

Fipronil acts by binding to allosteric sites of GABAA receptors and GluCl receptors (of insects) as an antagonist (a form of noncompetitive inhibition). This prevents the opening of chloride ion channels normally encouraged by GABA, reducing the chloride ions' ability to lower a neuron's membrane potential. This results in an overabundance of neurons reaching action potential and likewise CNS toxicity via overstimulation.[29][30][31][32]

- Acute oral LD50 (rat) 97 mg/kg

- Acute dermal LD50 (rat) >2000 mg/kg

In animals and humans, fipronil overdose is characterized by vomiting, agitation, and seizures, and can usually be managed through use of benzodiazepines [33][34]

History[]

Fipronil was discovered and developed by Rhône-Poulenc between 1985 and 1987, and placed on the market in 1993 under the B2 U.S. Patent 5,232,940 B2. Between 1987 and 1996, fipronil was evaluated on more than 250 insect pests on 60 crops worldwide, and crop protection accounted for about 39% of total fipronil production in 1997. Since 2003, BASF holds the patent rights for producing and selling fipronil-based products in many countries.

2017 Fipronil eggs contamination[]

The 2017 Fipronil eggs contamination is an incident in Europe and South Korea involving the spread of insecticide contaminated eggs and egg products. Chicken eggs were found to contain Fipronil and distributed to 15 European Union countries, Switzerland, and Hong Kong.[35][36] Approximately 700,000 eggs are thought to have reached shelves in the UK alone.[37] Eggs at 44 farms in Taiwan were also found with excessive Fipronil levels.[38]

See also[]

- Imidacloprid

- Insecticide

- Merial

- Pesticide toxicity to bees

References[]

- ^ Raymond-Delpech, Valérie; Matsuda, Kazuhiko; Sattelle, Benedict M.; Rauh, James J.; Sattelle, David B. (2005-09-20). "Ion channels: molecular targets of neuroactive insecticides". Invertebrate Neuroscience. 5 (3–4): 119–133. doi:10.1007/s10158-005-0004-9. ISSN 1354-2516. PMID 16172884. S2CID 12654353.

- ^ Karen Todd-Jenkins (2017). "Perception Versus Reality: Insecticide Resistance in Fleas". American Veterinarian.

- ^ Maddison, Jill E.; Page, Stephen W. (2008). Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology (Second ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 229. ISBN 9780702028588.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Fipronil". Pesticides News. 48: 20. 2000.

- ^ "Exotic Texas Ant". Texas A&M. 2008-04-12. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- ^ https://uk.frontline.com/products

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Revive Rotoiti Autumn 2011". Department of Conservation. 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "War on wasps in Abel Tasman". 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Vespex: Making wide-area wasp control a reality - WWF's Conservation Innovation Awards". wwf-nz.crowdicity.com.

- ^ (DOC), corporatename = New Zealand Department of Conservation. "Wasp control using Vespex". www.doc.govt.nz.

- ^ "Argentine ants". www.doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ Hainzl, D.; Casida, J. E. (1996). "Fipronil insecticide: Novel photochemical desulfinylation with retention of neurotoxicity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (23): 12764–12767. Bibcode:1996PNAS...9312764H. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.23.12764. PMC 23994. PMID 8917493.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fipronil Technical Fact Sheet, National Pesticide Information Center". Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ "Cockroach Control". 2013-03-31. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 11th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2017, pp. 894-895. ISBN 978-0-692-77499-1

- ^ Amrith S. Gunasekara & Tresca Troung (March 5, 2007). "Environmental Fate of Fipronil" (PDF). Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ June 2000 BBC News story "Anti-locust drive 'created havoc'".

- ^ Jacob, CRO; Hellen Maria Soares; Stephen Malfitano Carvalho; Roberta Cornélio Ferreira Nocelli; Osmar Malspina (2013). "Acute Toxicity of Fipronil to the Stingless Bee Scaptotrigona postica Latreille". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 90 (1): 69–72. doi:10.1007/s00128-012-0892-4. PMID 23179165. S2CID 35297535.

- ^ Paula Sackmann, Mauricio Rabinovich and Juan Carlos Corley J. (2001). "Successful Removal of German Yellowjackets (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) by Toxic Baiting" (PDF). pp. 811–816.

- ^ Hanna, Cause; Foote, David; Kremen, Claire (2012). "Short and long-term control of Vespula pensylvanica in Hawaii by fipronil baiting". Pest Management Science. 68 (7): 1026–1033. doi:10.1002/ps.3262. PMID 22392920.

- ^ Elise Kissling; BASF SE (2003). "BASF statement regarding temporary suspension of sales of crop protection products containing fipronil in France".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fipronil" (PDF). National Pesticides Communication Network. p. 3. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances (1996). "Fipronil. May 1996. New Pesticide Fact Sheet. US EPA Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances".

- ^ "Colony Collapse Disorder linked to Fipronil". Archived from the original on 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Aufavure J., Biron D. G., Vidau C., Fontbonne R., Roudel M., Diogon M., Viguès B., Belzunces L. P., Delbac F., Blot N. (2012) Parasite - insecticide interactions: a case study of Nosema ceranae and fipronil synergy on honeybee. Scientific Reports 2:326 – DOI: 10.1038/srep00326

- ^ Kairo G, Biron D.G, Ben A.F, Bonnet M, Tchamitchian S, Cousin M, ... & Brunet J.L (2017) Nosema ceranae, Fipronil and their combination compromise honey bee reproduction via changes in male physiology]. Scientific reports, 7(1), 8556.

- ^ "EFSA assesses risks to bees from fipronil". 27 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (16 July 2013). "EU to ban fipronil to protect honeybees". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Cole, L. M.; Nicholson, R. A.; Casida, J. E. (1993). "Action of Phenylpyrazole Insecticides at the GABA-Gated Chloride Channel". Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 46: 47–54. doi:10.1006/pest.1993.1035.

- ^ Ratra, G. S.; Casida, J. E. (2001). "GABA receptor subunit composition relative to insecticide potency and selectivity". Toxicol. Lett. 122 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00366-6. PMID 11489356.

- ^ WHO. Pesticide Residues in Food - 1997: Fipronil; International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization: Lyon, 1997.

- ^ Olsen RW, DeLorey TM (1999). "Chapter 16: GABA and Glycine". In Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Fisher SK, Albers RW, Uhler MD (eds.). Basic neurochemistry: molecular, cellular, and medical aspects (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. ISBN 978-0-397-51820-3.

- ^ Ramesh C. Gupta (2007). Veterinary Toxicology. pp. 502–503. ISBN 978-0-12-370467-2.

- ^ Mohamed F, Senarathna L, Percy A, Abeyewardene M, Eaglesham G, Cheng R, Azher S, Hittarage A, Dissanayake W, Sheriff MH, Davies W, Buckley NA, Eddleston M., Acute human self-poisoning with the N-phenylpyrazole insecticide fipronil--a GABAA-gated chloride channel blocker, J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(7):955-63.

- ^ "Eggs containing fipronil found in 15 EU countries and Hong Kong". BBC News. 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ^ News, ABC. "EU: 17 nations get tainted eggs, products in growing scandal". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (11 August 2017). "Egg contamination scandal widens as 15 EU states, Switzerland and Hong Kong affected". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ "Eggs at 44 farms in Taiwan found with excessive insecticide levels". Taiwan News. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

External links[]

- Fipronil Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- Fipronil in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fipronil. |

- Chloroarenes

- Convulsants

- Endocrine disruptors

- GABAA receptor negative allosteric modulators

- Insecticides

- Nitriles

- Trifluoromethyl compounds

- Pyrazoles

- Sulfoxides

- Chloride channel blockers

- Neurotoxins

- Synthetic insecticides

- French inventions