Genetic studies on Turkish people

This article relies too much on references to primary sources. (November 2018) |

Population genetics research has been conducted on the ancestry of the modern Turkish people (not to be confused with Turkic peoples) in Turkey. Such studies are relevant for the demographic history of the population as well as health reasons, such as population specific diseases.[1] Some studies have sought to determine the relative contributions of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, from where the Seljuk Turks began migrating to Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which led to the establishment of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in the late 11th century, and prior populations in the area who were culturally assimilated during the Seljuk and the Ottoman periods.

Turkish genomic variation, along with several other Western Asian populations, looks most similar to genomic variation of South European populations such as southern Italians.[2] Western Asian genomes, including Turkish ones, have been greatly influenced by early agricultural populations in the area; later population movements, such as those of Turkic speakers, also contributed.[2] A whole-genome sequencing study of Turkish genetics, conducted on 16 individuals, concluded that the Turkish population forms a cluster with Southern European and Mediterranean populations and that the predicted contribution from ancestral East Asian populations (presumably reflecting a Central Asian origin) is 21.7%.[1] However, that does not provide a direct estimate of a migration rate, because of factors such as the unknown original contributing populations.[1] The genetic variation of various populations in Central Asia "has been poorly characterized"; Western Asian populations may also be "closely related to populations in the east".[2]

Multiple studies have found similarities or common ancestry between Turkish people and present-day or historic populations in the Mediterranean, West Asia and the Caucasus.[3][4][5][6][7] Other studies have found that Turkish people cluster with Southern and Mediterranean European populations along with groups in the northern part of Southwest Asia (such as the populations from Caucasus, Northern Iraq, and Iran)[8] and have the lowest fixation index distance from Caucasus and Iranian-Syrian populations.[9] Multiple studies have also found Central Asian contributions.[4][10][11][12][13]

Central Asian connection[]

Several studies have investigated to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to Anatolia contributed to the gene pool of the Turkish people and the role of the 11th-century settlement by Oghuz Turks. Some studies suggested that, although the Turks' settlement of Anatolia was of cultural importance, including the introduction of the Turkish language and Islam, the genetic contribution from Central Asia may have been slight.[5][14] A 2020 global study looking at whole-genome sequences showed that Turks have relatively lower within-population shared identical-by-descent genomic fragments compared to the rest of the world, suggesting mixture of remote populations.[15]

Some of the Turkic peoples originated from Central Asia may be related to the Xiongnu.[16] Most (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences belong to Asian haplogroups, but nearly 11% belong to European haplogroups.[16] Thus, contacts between European and Asian populations predated the Xiongnu culture,[16] confirming results reported for two samples from an early 3rd century B.C. Scytho-Siberian population.[17]

A study published in 2003 looked at Human leukocyte antigen genes to investigate the affinity of certain Mongolian tribes with Germans and Anatolian Turks. It was found that Germans and Turks were equally distant to the Mongolian populations. No close relationship was found between Turks and Mongolians despite the close relationship of their languages and shared historical neighborhood.[18]

A study of 75 individuals from various parts of Turkey concluded that the "genetic structure of the mitochondrial DNAs in the Turkish population bears some similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations".[19]

A 2001 study comparing the populations of Mediterranean Europe and Turkic-speaking peoples of Central Asia estimated the Central Asian genetic contribution to current Anatolian Y-chromosome loci (one binary and six short tandem repeat) and mitochondrial DNA gene pool to be roughly 30%.[12] A 2004 high-resolution SNP analysis of Y-chromosomal DNA in samples collected from blood banks, sperm banks, and university students in eight regions of Turkey found evidence for a weak but detectable signal (<9%) of gene flow from Central Asia.[4] A 2006 study concluded that the true Central Asian contributions to Anatolia was 13% for males and 22% for females (with wide ranges of confidence intervals), and the language replacement in Turkey and might not have been in accordance with the elite dominance model.[10] It was later observed that the male contribution from Central Asia to the Turkish population with reference to the Balkans was 13%. For all non-Turkic speaking populations, the Central Asian contribution was higher than in Turkey.[11] According to the study, "the contributions ranging between 13%–58% must be considered with a caution because they harbor uncertainties about the state of pre-nomadic invasion and further local movements."[11]

In a 2015 study, Turkish samples were in the West Eurasian clade which consisted of "all of mainland Europe, Sardinia, Sicily, Cyprus, western Russia, the Caucasus, Turkey, and Iran, and some individuals from Tajikistan and Turkmenistan." In this study, ancestry from East Asia was also visible in Turkish samples, with events after 1000 CE generally involving Asian sources being important when it comes to the ancestry of Turkey and its region.[20]

As of 2017, Central Asian genetic variation has been poorly studied, with little or no whole genome sequencing data for countries such as Turkmenistan and Afghanistan.[2] Therefore, future comprehensive genome-wide studies are needed. Turkish people, and other Western Asian populations, may also be closely related to Central Asian populations such as those near Western Asia.[2]

Haplogroup distributions[]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2018) |

Over-reliant on one, outdated source, Cinnioğlu 2004. (March 2018) |

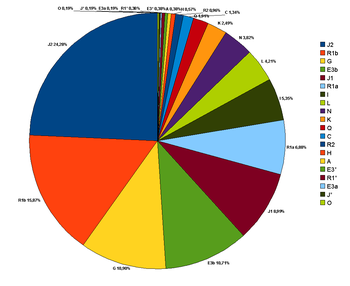

Cinnioğlu et al. (2004)[4] found many Y-DNA haplogroups in Turkey. Most haplogroups in Turkey are shared with its West Asian and Caucasian neighbors. The most common haplogroup in Turkey is J2 (24%), which is widespread among Mediterranean, Caucasian, and West Asian populations. Haplogroups that are common in Europe (R1b and I; 20%), South Asia (L, R2, H; 5.7%), and Africa (A, E3*, E3a; 1%) are also present. By contrast, Central Asian haplogroups (C, Q, and O) are rarer. However, the figure may rise to 36% if K, R1a, R1b, and L—which infrequently occur in Central Asia but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups—are included. J2 is also frequently found in Central Asia, a notably high frequency (30.4%) being observed among Uzbeks.[21]

The main percentages identified were as follows:[4]

- J2: 24%. J2 (M172) may reflect the spread of Anatolian farmers.[22] J2-M172 is "mainly confined to the Mediterranean coastal areas, southeastern Europe and Anatolia", as well as West Asia and Central Asia.[23]

- R1b: 15.9%. R1b is found in Europe, West Asia, Central Asia, Southern Asia, some parts of the Sahel region of Africa.[24]

- G: 10.9%. Haplogroup G has also been associated with the spread of agriculture (together with J2 clades) and is "largely restricted to populations of the Caucasus and the Near/Middle East and southern Europe."[25]

- E3b-M35: 10.7% (E3b1-M78 and E3b3-M123 accounting for all E representatives in the sample, besides a single E3b2-M81 chromosome). E-M78 is common along a line from the Horn of Africa via Egypt to the Balkans.[26] Haplogroup E-M123 is found in both Africa and Eurasia.

- J1: 9%

- R1a: 6.9%

- I: 5.3%

- K: 4.5%

- L: 4.2%

- N: 3.8%

- T: 2.5%

- Q: 1.9%

- C: 1.3%

- R2: 0.96%

Other markers that occurred in less than 1% are H, A, E3a, O, and R1*.

Further research on Turkish Y-DNA groups[]

A 2008 study[27] took into account oral histories and historical records. The researchers went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and chose a random selection of subjects from among university students.

In an Afshar village near Ankara where, according to oral tradition, the ancestors of the inhabitants came from Central Asia, the researchers found that 57% of the villagers had haplogroup L, 13% had haplogroup Q and 3% had haplogroup N. Examples of haplogroup L, which is most common in South Asia, might be a result of Central Asian migration even though the presence of haplogroup L in Central Asia itself was most likely a result of migration from South Asia. Therefore, Central Asian haplogroups potentially occurred in 73% of males in the village. Furthermore, 10% of the Afshars had haplogroups E3a and E3b, while only 13% had haplogroup J2a, the most common in Turkey.

By contrast, the inhabitants of a traditional Turkish village that had little migration had about 25% haplogroup N and 25% J2a, with 3% G and close to 30% R1 variants (mostly R1b).

Whole genome sequencing[]

A study of Turkish genetics in 2014 used whole genome sequencing of individuals.[1] It found that the genetic variation of contemporary Turks clusters with South European populations, as expected, but also shows signatures of relatively recent contribution from ancestral East Asian populations. It estimated the weight for the migration events predicted to originate from the East Asian branch into Turkey at 21.7% (see image).[1]

Other studies[]

A 2001 study that looked at HLA alleles suggested that "Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Iranians, Jews, Lebanese and other (Eastern and Western) Mediterranean groups seem to share a common ancestry" and that historical populations such as Anatolian Hittite and Hurrian groups (older than 2000 B.C.) "may have given rise to present‐day Kurdish, Armenian and Turkish populations."[3] A 2004 study that looked at 11 human‐specific Alu insertion polymorphisms among Aromanians, North Macedonians, Albanians, Romanians, Greeks, and Turks, suggested a common ancestry for these populations.[28]

A 2011 study ruled out long-term and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between these regions, with minimal admixture. The research also confirmed the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.[7]

A study in 2015, however, wrote, "Previous genetic studies have generally used Turks as representatives of ancient Anatolians. Our results show that Turks are genetically shifted towards Central Asians, a pattern consistent with a history of mixture with populations from this region." The authors found "7.9% (±0.4) East Asian ancestry in Turks from admixture occurring 800 (±170) years ago."[13]

According to a 2012 study of ethnic Turks, "Turkish population has a close genetic similarity to Middle Eastern and European populations and some degree of similarity to South Asian and Central Asian populations."[29] The analysis modeled each person's DNA as having originated from K ancestral populations and varied the parameter K from 2 to 7. At K = 3, comparing to individuals from the Middle East (Druze and Palestinian), Europe (French, Italian, Tuscan and Sardinian) and Central Asia (Uygur, Hazara and Kyrgyz), clustering results indicated that the contributions were 45%, 40% and 15% for the Middle Eastern, European and Central Asian populations, respectively. At K = 4, results for paternal ancestry were 38% European, 35% Middle Eastern, 18% South Asian, and 9% Central Asian. At K = 7, results of paternal ancestry were 77% European, 12% South Asian, 4% Middle Eastern, and 6% Central Asian. However, results may reflect either previous population movements (such as migration and admixture) or genetic drift.[29] The Turkish samples were closest to the Adygei population (Circassians) from the Caucasus; other sampled groups included European (French, Italian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South Asian (Pakistani), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.[29]

A study involving mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine-era population, whose samples were gathered from excavations in the archaeological site of Sagalassos, found that these samples were closest to modern samples from "Turkey, Crimea, Iran and Italy (Campania and Puglia), Cyprus and the Balkans (Bulgaria, Croatia, and Greece)."[30] Modern-day samples from the nearby town of Ağlasun showed that lineages of East Eurasian descent assigned to macro-haplogroup M were found in the modern samples from Ağlasun. This haplogroup was significantly more frequent in Ağlasun (15%) than in Byzantine Sagalassos, but the study found "no genetic discontinuity across two millennia in the region."[31]

A 2019 study found that Turkish people cluster with Southern and Mediterranean Europe populations along with groups in the northern part of Southwest Asia (such as the populations from Caucasus, Northern Iraq, and Iranians).[8] Another 2019 study found that Turkish people have the lowest fixation index distances with Caucasus population group and Iranian-Syrian group, as compared to East-Central European, European (including Northern and Eastern European), Sardinian, Roma, and Turkmen groups or populations. The Caucasus group in the study included samples from Abkhazians, Adygey, Armenians, Balkars, Chechens, Georgians, Kumyks, Kurds, Lezgins, Nogays, and North Ossetians.[9]

See also[]

- Demographics of Turkey

- History of the Turkish people

- Genetic history of the Middle East

- Genetic history of Europe

- Turkification

References and notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Alkan C, Kavak P, Somel M, Gokcumen O, Ugurlu S, Saygi C, et al. (November 2014). "Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa". BMC Genomics. 15: 963. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-963. PMC 4236450. PMID 25376095.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Taskent RO, Gokcumen O (April 2017). "The Multiple Histories of Western Asia: Perspectives from Ancient and Modern Genomes". Human Biology. 89 (2): 107–117. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.89.2.01. PMID 29299965. S2CID 6871226.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arnaiz-Villena A, Karin M, Bendikuze N, Gomez-Casado E, Moscoso J, Silvera C, et al. (April 2001). "HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans". Tissue Antigens. 57 (4): 308–17. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x. PMID 11380939.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Cinnioğlu C, King R, Kivisild T, Kalfoğlu E, Atasoy S, Cavalleri GL, et al. (January 2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639. S2CID 10763736.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosser ZH, Zerjal T, Hurles ME, Adojaan M, Alavantic D, Amorim A, et al. (December 2000). "Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–43. doi:10.1086/316890. PMC 1287948. PMID 11078479.

- ^ Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Underhill PA, Evseeva I, Blue-Smith J, et al. (August 2001). "The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. JSTOR 3056514. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schurr TG, Yardumian A (2011). "Who Are the Anatolian Turks?". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 50 (1): 6–42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101. S2CID 142580885.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pakstis AJ, Gurkan C, Dogan M, Balkaya HE, Dogan S, Neophytou PI, et al. (December 2019). "Genetic relationships of European, Mediterranean, and SW Asian populations using a panel of 55 AISNPs". European Journal of Human Genetics. 27 (12): 1885–1893. doi:10.1038/s41431-019-0466-6. PMC 6871633. PMID 31285530.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bánfai Z, Melegh BI, Sümegi K, Hadzsiev K, Miseta A, Kásler M, Melegh B (2019). "Revealing the Genetic Impact of the Ottoman Occupation on Ethnic Groups of East-Central Europe and on the Roma Population of the Area". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 558. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00558. PMC 6585392. PMID 31263480.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berkman C (September 2006). Comparative Analyses for the Central Asian Contribution to Anatolian Gene Pool with Reference to Balkans (PDF) (PhD Thesis). Middle East Technical University. p. v.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Berkman CC, Togan İ (2009). "The Asian contribution to the Turkish population with respect to the Balkans: Y-chromosome perspective". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 157 (10): 2341–8. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2008.06.037.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Di Benedetto G, Ergüven A, Stenico M, Castrì L, Bertorelle G, Togan I, Barbujani G (June 2001). "DNA diversity and population admixture in Anatolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 115 (2): 144–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.515.6508. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1064. PMID 11385601.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haber M, Mezzavilla M, Xue Y, Comas D, Gasparini P, Zalloua P, Tyler-Smith C (June 2016). "Genetic evidence for an origin of the Armenians from Bronze Age mixing of multiple populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (6): 931–6. bioRxiv 10.1101/015396. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.206. PMC 4820045. PMID 26486470. S2CID 196677148.

- ^ Arnaiz-Villena A, Gomez-Casado E, Martinez-Laso J (August 2002). "Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective". Tissue Antigens. 60 (2): 111–21. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x. PMID 12392505.

- ^ Khvorykh GV, Mulyar OA, Fedorova L, Khrunin AV, Limborska SA, Fedorov A (2020). "Global Picture of Genetic Relatedness and the Evolution of Humankind". Biology (Basel). 9 (11): 392. doi:10.3390/biology9110392. PMC 7696950. PMID 33182715.

Due to a historically high number of admixed people and large population sizes, the numbers of shared IBD fragments within the same population in the aforementioned groups are the lowest compared to the rest of the world (for Pathans, their shared number of IBDs among themselves is the record low—8.95; this is followed by Azerbaijanians and Uyghurs, each at 10.8; Uzbeks at 11.1; Iranians at 12.2; and Turks at 12.9). Together, the low number of shared IBDs within the same population and the high values for relative relatedness from multiple DHGR components (Supplementary Table S4) indicate the populations with the strongest admixtures where millions of people from remote populations mixed with each other for hundreds of years. In Europe, such admixed populations include the Moldavians, Greeks, Italians, Hungarians, and Tatars, among others. In the Americas, the highest admixture was detected in the Mexicans from Los Angeles (MXL) and Peruvians (PEL) presented by the 1000 Genomes Project.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b c Keyser-Tracqui C, Crubézy E, Ludes B (August 2003). "Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (2): 247–60. doi:10.1086/377005. PMC 1180365. PMID 12858290.

- ^ Clisson I, Keyser C, Francfort HP, Crubezy E, Samashev Z, Ludes B (October 2002). "Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, Early 3rd Century BC)". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 116 (5): 304–8. doi:10.1007/s00414-002-0295-x. PMID 12376844. S2CID 27711154.

- ^ Machulla HK, Batnasan D, Steinborn F, Uyar FA, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Oguz FS, Carin MN, Dorak MT. "Genetic affinities among Mongol ethnic groups and their relationship to Turks". Tissue Antigens. 2003 Apr;61(4):292-9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00043.x.

- ^ Mergen H, Oner R, Oner C (April 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey)" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 83 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1007/bf02715828. PMID 15240908. S2CID 23098652.

- ^ Busby GB, Hellenthal G, Montinaro F, Tofanelli S, Bulayeva K, Rudan I; et al. (2015). "The Role of Recent Admixture in Forming the Contemporary West Eurasian Genomic Landscape". Curr Biol. 25 (19): 2518–26. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.007. PMC 4714572. PMID 26387712.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians Shou WH, Qiao EF, Wei CY, Dong YL, Tan SJ, Shi H, et al. (May 2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–22. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30. PMID 20414255.

- ^ Semino O, Magri C, Benuzzi G, Lin AA, Al-Zahery N, Battaglia V, et al. (May 2004). "Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- ^ Shou WH, Qiao EF, Wei CY, Dong YL, Tan SJ, Shi H, et al. (May 2010). "Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (5): 314–22. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.30. PMID 20414255.

- ^ Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, et al. (January 2011). "A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. PMC 3039512. PMID 20736979.

- ^ Rootsi S, Myres NM, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, et al. (December 2012). "Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (12): 1275–82. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.86. PMC 3499744. PMID 22588667.

- ^ Cruciani F, La Fratta R, Torroni A, Underhill PA, Scozzari R (August 2006). "Molecular dissection of the Y chromosome haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): a posteriori evaluation of a microsatellite-network-based approach through six new biallelic markers". Human Mutation. 27 (8): 831–2. doi:10.1002/humu.9445. PMID 16835895. S2CID 26886757.

- ^ Gokcumen O (2008). Ethnohistorical and genetic survey of four Central Anatolian settlements (Thesis). pp. 1–189. ISBN 9783845258546. OCLC 857236647.[page needed]

- ^ Comas D, Schmid H, Braeuer S, Flaiz C, Busquets A, Calafell F, et al. (March 2004). "Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 2): 120–7. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x. PMID 15008791. S2CID 21773796.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hodoğlugil U, Mahley RW (March 2012). "Turkish population structure and genetic ancestry reveal relatedness among Eurasian populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 76 (2): 128–41. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. PMC 4904778. PMID 22332727.

- ^ Ottoni C, Ricaut FX, Vanderheyden N, Brucato N, Waelkens M, Decorte R (May 2011). "Mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine population reveals the differential impact of multiple historical events in South Anatolia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (5): 571–6. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.230. PMC 3083616. PMID 21224890.

- ^ Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey Ottoni C, Rasteiro R, Willet R, Claeys J, Talloen P, Van de Vijver K, et al. (February 2016). "Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey". Royal Society Open Science. 3 (2): 150250. Bibcode:2016RSOS....350250O. doi:10.1098/rsos.150250. PMC 4785964. PMID 26998313.

- Genetics by country

- Modern human genetic history

- Ethnic Turkish people

- Genetics by ethnicity