History of Sydney

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

|

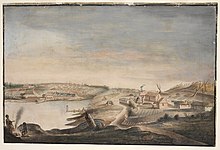

The History of Sydney begins in prehistoric times with the occupation of the district by Australian Aboriginals, whose ancestors came to Sydney in the Upper Paleolithic period.[1] The modern history of the city began with the arrival of a First Fleet of British ships in 1788 and the foundation of a penal colony by Great Britain.

From 1788 to 1900 Sydney was the capital of the British colony of New South Wales. An elected city council was established in 1840. In 1901, Sydney became a state capital, when New South Wales voted to join the Australian Federation. Sydney today is Australia's largest city and a major international capital of culture and finance. The city has played host to many international events, including the 2000 Summer Olympics.

Prehistory[]

The first people to occupy the area now known as Sydney were Australian Aboriginals. Radiocarbon dating suggests that they lived in and around Sydney for at least 30,000 years.[2] In an archaeological dig in Parramatta, Western Sydney, it was found that the Aboriginals used charcoal, stone tools and possible ancient campfires.[3] Near Penrith, a far western suburb of Sydney, numerous Aboriginal stone tools were found in Cranebrook Terraces gravel sediments having dates of 45,000 to 50,000 years BP. This would mean that there was human settlement in Sydney earlier than thought.[4]

Prior to the arrival of the British there were 4,000 to 8,000 native people in the Sydney area from as many as 29 different clans.[5] Sydney Cove from Port Jackson to Petersham was inhabited by the Cadigal clan.[5] The principal language groups were Darug, Guringai, and Dharawal. The earliest Europeans to visit the area noted that the indigenous people were conducting activities such as camping and fishing, using trees for bark and food, collecting shells, and cooking fish.[6]

The area surrounding Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) was home to several Aboriginal tribes. The "Eora people" are the coastal Aborigines of the Sydney district. The name Eora simply means "here" or "from this place", and was used by Local Aboriginal people to describe to the British where they came from. The Cadigal band are the traditional owners of the Sydney CBD area, and their territory south of Port Jackson stretches from South Head to Petersham.

Consequently, they were first to suffer the effects of dispossession when the British arrived, though the descendants of Eora still have a strong presence in the Sydney area today. Other than the Eora, people of the Dharug, Kuringgai and Dharawal language groups occupied the lands in and around Sydney.[7] Their occupation pre-dates the arrival of the First Fleet of British by some thousands of years. Examples of Aboriginal stone tools and Aboriginal art (often recording the stories of the Dreamtime religion) can be found throughout New South Wales: even within the metropolis of modern Sydney, as in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park.[8]

Arrival of Great Britain[]

On 19 April 1770, the crew of HMS Endeavour, under the command of Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook, were the first known Europeans to sight the east coast of Australia. Ten days later they came across an extensive but shallow inlet, and upon entering it moored off a low headland fronted by sand dunes. The ship's naturalist, Sir Joseph Banks, was so impressed by the volume of flora and fauna hitherto unknown to European science, that Cook named the inlet Botany Bay, on the Kurnell Peninsula, just near Silver Beach, and made contact of a hostile nature with the Gweagal Aborigines, on 29 April.

At first Cook bestowed the name "Sting-Ray Harbour" to the inlet after the many such creatures found there; this was later changed to "Botanist Bay" and finally Botany Bay after the unique specimens retrieved by the botanists Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander and Herman Spöring.[9] Cook charted the east coast to its northern extent and, on 22 August, at Possession Island in the Torres Strait, took possession of the coast in the name of King George III of Great Britain. Cook and Banks then reported favourably to London on the possibility of establishing a British colony at Botany Bay.

The British colony of New South Wales was subsequently established with the arrival of the First Fleet of 11 vessels under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip in January 1788. It consisted of over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (192 women and 586 men).[10] Phillip soon decided that Botany Bay, chosen on the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks, who had accompanied James Cook in 1770, was not suitable, since it had poor soil, no secure anchorage and no reliable water source.[11] A few days after arrival at Botany Bay the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788.[12] This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney.

Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and Port Jackson a safe harbour, which Phillip described as:[13]

'being without exception the finest Harbour in the World

Phillip originally named the colony "New Albion", but for some uncertain reason the colony acquired the name "Sydney", after the (then) British Home Secretary, Thomas Townshend, Lord Sydney (Baron Sydney, Viscount Sydney from 1789).[citation needed] This is possibly because Lord Sydney issued the charter authorising Phillip to establish a colony. Phillip visited the Manly Cove area, between 21 and 23 January 1788 and was so impressed by the confident and manly behaviour of the local Aboriginal people of the Cannalgal and Kayimai clans who waded out to meet his boat in North Harbour, that he gave the cove the name Manly Cove.[14]

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Enlightened for his age, Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers—most notably Watkin Tench—left behind journals and accounts of which tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement. Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of Sydney. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce.

Between 1788 and 1792 about 3,546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney—many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its "passengers" through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791 on, however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.[15]

Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils and fixed on the Parramatta region as a promising area for expansion and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life, leaving Sydney Cove only as an important port and focus of social life. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soils and climate continued to hamper the expansion of farming from Farm Cove to Parramatta and Toongabbie, but a building programme, assisted by convict labour, advanced steadily.

Impact on Sydney Indigenous people[]

European settlement had a disastrous impact on the local Aboriginal people. In the early days of the colony this was mainly due to depletion of local food stocks and the advent of introduced diseases such as measles, possibly chicken pox, venereal disease and smallpox, to which the Aboriginal population had no genetic immunity. Contrary to later trends, Governor Phillip in fact enforced strict rules of behaviour for interaction between settlers and native people, and his policy was remarkably enlightened by the standards of the time. In April 1789, however, twelve months after the departure from Botany Bay by the French expedition led by Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, a catastrophic epidemic of smallpox (or possibly chicken pox) spread through the Eora people and surrounding groups, with the result that local Aborigines died in their hundreds.

Author and First Fleet officer Watkin Tench, whose accounts are primary sources about the early years of the colony, suggested that the epidemic may have been caused by Aborigines disturbing the grave of a French sailor who died shortly after arrival in Australia and had been buried at Botany Bay. However, in his memoir A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales", Tench wrote that he had never heard of the existence of smallpox among the French sailors. Another intriguing possibility mentioned by Tench was that, as the colony's physicians had brought bottles of smallpox-infected material with them from England for use in inoculation against smallpox.[16]

Historian Judy Campbell argues that it is highly improbable that the First Fleet was the source of the epidemic as "smallpox had not occurred in any members of the First Fleet"; the only possible source of infection from the Fleet being Tench's "bottles". She points to regular contact between fishing fleets from the Indonesia archipelago, where smallpox was endemic, and Aboriginal people in Australia's North as a far more likely source for the introduction of smallpox.[17] Other historians have argued that it is likely that the outbreak came from First Fleet sources.[18] This area has been highly contentious, but in the 2014 review by Christopher Warren, in Journal of Australian Studies it was argued that British marines were most likely to have spread smallpox without the knowledge of Governor Phillip.[19]

Between 1788 and 1792, convicts and their jailers made up the majority of the population; in one generation, however, a population of emancipated convicts who could be granted land began to grow. These people pioneered Sydney's private sector economy and were later joined by soldiers whose military service had expired, and later still by free settlers who began arriving from Britain. Governor Phillip departed the colony for England on 11 December 1792, with the new settlement having survived near starvation and immense isolation for four years.

Aboriginal resistance and conflicts[]

With the expansion of European settlement large amounts of land was cleared for farming, which resulted in the destruction of Aboriginal food sources. This, combined with the introduction of new diseases such as smallpox, caused resentment within the Aboriginal clans against the British and resulted in violent confrontations.[20]

Pemulwuy, an Aboriginal Political leader, is notable for his resistance to the European settlement of Australia. He persuaded the Eora, Dharug and Tharawal people to join his campaign against the newcomers. From 1792 Pemulwuy led raids on settlers from Parramatta, Georges River, Prospect, Toongabbie, Brickfield Hill and Hawkesbury River. His most common tactic was to burn crops and kill livestock. Whether Pemulwuy was actively resisting European settlement, or was only attempting to uphold Aboriginal law, which often involved revenge acts, is debated by historians. Regardless, the British believed the attacks made against them were acts of war.[21]

In March 1797, Pemulwuy led a group of Aboriginal warriors, estimated to be at least 100, in an attack on a government farm at Toongabbie. At dawn the next day government troops and settlers followed them to Parramatta. When confronted, Pemulwuy threw a spear at a soldier prompting the government troops and settlers to open fire. Pemulwuy was the first to be shot and wounded. The Aboriginal warriors threw many spears, hitting one man in the arm. The difference in firepower was evident and five Aboriginal warriors were killed instantly.[22] This incident has more recently become known as the Battle of Parramatta.[23][24][25][26]

The Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars (1795–1816) were a series of wars between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Indigenous clans of the Hawkesbury and Nepean Rivers in northwest Sydney. It was fought using mostly guerrilla-warfare tactics; however, several conventional battles also took place. The wars resulted in the defeat of the Hawkesbury and Nepean Indigenous clans who were subsequently dispossessed of their lands.[27]

Sydney Town[]

Early Sydney was moulded by the hardship suffered by early settlers. In the early years, drought and disease caused widespread problems, but the situation soon improved. The military colonial government was reliant on the army, the New South Wales Corps (also known as the "Rum Corps" due to their monopoly on the importation of alcohol).

Conditions for convicts in the penal colony were harsh. In 1804, Irish convicts led the Castle Hill Rebellion.[28] Conflicts arose between the governors and the officers of the Rum Corps, many of which were land owners such as John Macarthur. In 1808 these conflicts came to open rebellion, with the Rum Rebellion, in which the Rum Corps ousted Governor William Bligh (known from the mutiny on the Bounty).

The New South Wales Corps was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment to relieve the marines who had accompanied the First Fleet. Officers of the Corps soon became involved in the corrupt and lucrative rum trade in the colony. In the Rum Rebellion of 1808, the Corps, working closely with the newly established wool trader John Macarthur, staged the only successful armed takeover of government in Australian history, deposing Governor William Bligh and instigating a brief period of military rule in the colony prior to the arrival from Britain of Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810.[29]

Macquarie served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, from 1810 to 1821 and had a leading role in the social and economic development of Sydney which saw it transition from a penal colony to a budding free society. He established public works, a bank, churches, and charitable institutions and sought good relations with the Indigenous population although the motivations behind were still embedded in colonial dominance. In 1813 he sent Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson across the Blue Mountains, where they found the great plains of the interior. Central, however to Macquarie's policy was his treatment of the emancipists, whom he decreed should be treated as social equals to free-settlers in the colony. Against opposition, he appointed emancipists to key government positions including Francis Greenway as colonial architect and William Redfern as a magistrate. London judged his public works to be too expensive and society was scandalised by his treatment of emancipists.[30]

Governor and Mrs Macquarie preferred the clean air of rural Parramatta to the unsanitary and crime-ridden streets of Sydney Town and transformed Old Government House, Parramatta, into an elegant Palladian-style home in the English manner. Originally constructed under Governor John Hunter in 1799 to reflect the economic importance of the Parramatta district, the building remains today Australia's oldest public building and was given World Heritage Listing by UNESCO in 2010.[31]

1850s Gold Rush and economic power[]

Australia experienced a number of gold rushes in the mid-19th century, beginning with the discovery of gold in Bathurst (150 km west of Sydney) in 1851. Large numbers of immigrant miners poured into Sydney and the population grew from 39,000 to 200,000 people 20 years later. Demand for infrastructure to support the growing population and subsequent economic activity led to massive improvements to the city's railway and port systems throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

After a period of rapid growth, further discoveries of gold in Victoria began drawing new residents away from Sydney towards Melbourne and a great rivalry began to grow between the two cities. The rivalry culminated as Australia moved to become a federation and both Melbourne and Sydney lobbied to be officially recognised as the capital city (a dispute settled with the creation of a new city, Canberra, instead).[32]

Political development[]

The first government established in Sydney after 1788 was an autocratic system run by an appointed governor – although English law was transplanted into the Australian colonies by virtue of the doctrine of reception, thus notions of the rights and processes established by the Magna Carta of 1215 and the Bill of Rights of 1689 were brought from Britain by the colonists. Agitation for representative government began soon after the settlement of the colonies.[33]

The oldest legislative body in Australia, the New South Wales Legislative Council, was created in Sydney in 1825 as an appointed body to advise the Governor of New South Wales. The northern wing of Macquarie Street's's Rum Hospital was requisitioned and converted to accommodate the first Parliament House in 1829, as it was the largest building available in Sydney at the time.[34]

William Wentworth established the Australian Patriotic Association (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist attorney general, John Plunkett, sought to apply Enlightenment principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, by extending jury rights to emancipists, then legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and Aborigines and legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.[35]

In 1838, the celebrated humanitarian Caroline Chisholm arrived at Sydney and soon after began her work to alleviate the conditions for the poor women migrants. She met every immigrant ship at the docks, found positions for immigrant girls and established a Female Immigrants' Home. Later she began campaigning for legal reform to alleviate poverty and assist female immigration and family support in the colonies.[36]

In 1842 the Sydney City Council was established with a limited franchise. Men who possessed property valued at £1000 (or £50 per year) were able to stand for election. Every adult male over 21 years who occupied a "house warehouse counting-house or shop" valued at £25 per year was permitted to vote in one of four wards – this amounted to only around 15% of the adult population. Plural voting was prohibited by the enabling legislation.[37][38] Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity.[39] The passing of the Sydney Incorporation Act in 1842 officially recognised the colonial settlement as a township, enabled the taxation of property owners and occupiers, and imposed a managerial structure to its administration.

The first elected aldermen met in public houses, among their constituents, but began campaigning for a civic hall. They chose the run down site of Sydney's first official European cemetery: on George Street, in the commercial heart of the city and organised for Sydney's first royal visitor, HRH Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, to lay a foundation stone on 4 April 1868, even before colonial authorities on Macquarie Street had approved the plan. That same year, a design for the Sydney Town Hall by architect J. H. Willson was chosen which took its inspiration from the French style of the Hotel de Ville de Paris. To this day, the Hall remains the civic office of the Lord Mayor of Sydney and aldermen of the City Council.

The end of convict transportation and the rapid growth of population following the Australian gold rushes led to further demands for "British institutions" in New South Wales, which meant an elected parliament and responsible government. In 1851 the franchise for the Legislative Council was expanded and 1857 saw the granting of the right to vote to all male British subjects 21 years or over in New South Wales[39] and from the 1860s onwards government in New South Wales became increasingly stable and assured.

Cultural development[]

Over the course of the 19th-century Sydney established many of its major cultural institutions. Governor Lachlan Macquarie's vision for Sydney included the construction of grand public buildings and institutions fit for a colonial capital. Macquarie Street began to take shape as a ceremonial thoroughfare of grand buildings. He founded the Royal Botanic Gardens and dedicated Hyde Park to the "recreation and amusement of the inhabitants of the town and a field of exercises for the troops".

Macquarie set aside a large portion of land for an Anglican Cathedral and laid the foundation stone for the first St Mary's Catholic Cathedral in 1821. St Andrew's Anglican Cathedral, though more modest in size than Macquarie's original vision, later began construction and, after fire and setbacks, the present St Mary's Catholic Cathedral foundation stone was laid in 1868, from which rose a towering gothic-revival landmark.[40] Religious groups were also responsible for many of the philanthropic activities in Sydney. One of these was the Sydney Female Refuge Society set up to care for prostitutes in 1848.[41]

The first Sydney Royal Easter Show, an agricultural exhibition, began in 1823.[42] Alexander Macleay started collecting the exhibits of Australia's oldest museum–Sydney's Australian Museum–in 1826 and the current building opened to the public in 1857.[43] The University of Sydney was established in 1850. The Royal National Park, south of the city opened in 1879 (second only to Yellowstone National Park in the USA).

An academy of art formed in 1870 and the present Art Gallery of New South Wales building began construction in 1896.[44] Inspired by the works of French impressionism, artists camps formed around the foreshores of Sydney Harbour in the 1880s and 1890s at idyllique locations such as Balmoral Beach and Curlew Camp in Sirius Cove. Artists such as Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts of the Heidelberg School worked here at this time and created some of the masterpieces of newly developing and distinctively Australian styles of painting.[45]

Australia's first rugby union club, the Sydney University Football Club, was founded in Sydney in the year 1863.[46] The New South Wales Rugby Union (or then, The Southern RU – SRU) was established in 1874, and the tradition of an annual club competition began in Sydney that year. Initially widely popular, the code would later assume secondary popularity in Sydney, when in 1907, the New South Wales Rugby League was established and would grow to be the favourite football code of the city. In 1878 the inaugural first class cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground was played between New South Wales and Victoria.[47] The Athletic Association of the Great Public Schools of New South Wales (A.A.G.P.S) was established in Sydney 1892 and interschool rugby and athletics competitions began that year, followed by cricket and rowing the following year.[48]

The Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 showcased the colonial capital to the world. Some exhibits from this event were kept to constitute the original collection of the new Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum of New South Wales (today's Powerhouse Museum).

Many grand public buildings were built during the 19th century. The Romanesque landmark Queen Victoria Building (QVB), designed by George McRae, was completed in 1898 on the site of the old Sydney markets. Built as a monument to the popular and long reigning monarch, Queen Victoria, construction took place while the city was in severe recession and construction of the ornate structure helped employ out of work stonemasons, plasterers, and stained window artists. Restored in the late 20th century, the building remains a boutique shopping and dining hall. Sydney's preservation of heritage buildings, particularly Victorian terrace houses, has drawn comparisons to "parts of London, particularly given the predominance of the London terrace".[49]

Sydney's first newspaper was the Sydney Gazette established, edited and distributed by George Howe. It appeared irregularly between 1803 and 1842, but nonetheless provides a valuable source on the early development of the colony based at Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald joined the Sydney Gazette as a daily publication in 1831; it continues to be published to this day.[50] Two Sydney journalists, J. F. Archibald and John Haynes, founded The Bulletin magazine; the first edition appeared on 31 January 1880. It was intended to be a journal of political and business commentary, with some literary content. Initially radical, nationalist, democratic, and racist, it gained wide influence and became a celebrated entry-point to publication for Australian writers and cartoonists such as Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Miles Franklin, and the illustrator and novelist Norman Lindsay.[51]

Transport[]

Ferries[]

Ferries have played a key role in the transport and economic development of the city. Leading up to the 1932 opening of the Sydney Harbour bridge, Sydney had the world's largest ferry fleet.

From the time of the first European settlement in Sydney Cove, slow and sporadic boats ran along the Parramatta River serving Parramatta and the agricultural settlements in between. By the mid-1830s, speculative ventures established regular services. From the late-nineteenth century the North Shore developed rapidly. A rail connection to Milsons Point took alighting ferry passengers up the North Shore line to Hornsby via North Sydney. Without a bridge connection, increasingly large fleets of steamers serviced the cross harbour routes and in the early twentieth century, Sydney Ferries Limited was the largest ferry operator in the world.

Arguably the most well-known is the Manly ferry service, and its large ship-like ferries that negotiate the beam swells of the Sydney Heads. From the mid-nineteenth century, the Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Company and its forerunners ran commuter and weekend excusioner services to the beach-side suburb.

The 1932 opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge dramatically and permanently changed Sydney Harbour. Sydney Ferries Limited annual patronage fell from 40 million to 15 million almost immediately. The hardships of the Great Depression and Second World War slowed the ferries' decline, but by 1951 the NSW State Government was forced to take over the ailing Sydney Ferries Limited. The Port Jackson company had fared better and their peak year was 1946, after which a slow decline saw it too taken over by the NSW State Government in the 1970s. Ferry operations were privatised in 2015 with vessels and facilities remaining in public ownership.

Trams[]

Sydney once had the largest tram system in Australia, the second largest in the British Commonwealth (after London), and one of the largest in the world. It was extremely intensively worked, with about 1,600 cars in service at any one time at its peak during the 1930s (cf. about 500 trams in Melbourne today).

Sydney's first tram was horse-drawn, running from the old Sydney Railway station to Circular Quay along Pitt Street.[52] Built in 1861, the design was compromised by the desire to haul railway freight wagons along the line to supply city businesses, in addition to passenger traffic. This resulted in a track that protruded from the road surface and damaged the wheels of wagons trying to cross it. Hard campaigning by competing omnibus owners – as well as the fatal accident involving the leading Australian musician Isaac Nathan in 1864 – led to closure in 1866.

In 1879 a steam tramway was established.[53] The System was a great success and the network expanded rapidly through the city and inner suburbs. There were also two cable tram routes, to Ocean Street (Edgecliff) and in North Sydney, later extended to Crows Nest, because of the steep terrain involved.[54]

Electrification started in 1898, and most of the system was converted by 1910. The privately owned Parramatta to Redbank Wharf (Duck River) steam tram remained until 1943.[55]

By the 1920s, the system had reached its maximum extent. The overcrowded and heaving trams running at a high frequency, in competition with growing private motor car and bus use, created congestion. Competition from the private car, private bus operators and the perception of traffic congestion led to the gradual closure of lines from the 1940s. Overseas transport experts were called upon to advise the city on its post-war transport issues and recommended closure of the system, but generally went against public opinion. Nevertheless, closure became Labor government policy and the system was wound down in stages, with withdrawal of the last service, to La Perouse, in 1961.

20th century[]

Federation, Great War and Great Depression[]

With the inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901, Sydney ceased to be a colonial capital and became the capital of the Australian state of New South Wales. With industrialisation, Sydney expanded rapidly, and by the early 20th century it had a population well in excess of one million.

With the close of the Victorian Era, the character of Sydney began to change in various ways. During the 19th century, Sydney's beaches had become popular seaside holiday resorts, but daylight sea bathing was considered indecent until the early 20th century. In defiance of these restrictions, in October 1902, William Gocher, wearing a neck to knee costume, entered the water at Manly Beach only to be escorted from the water by the police – but the following year, Manly Council removed restrictions on all-day bathing – provided neck to knee swimming costumes were worn – and Sydney's love affair with sun and surf flourished.[14] Arguably the world's first surf lifesaving club was founded at Bondi Beach, Sydney, in 1906. In the summer of 1915, Duke Kahanamoku of Hawaii introduced surf board riding to Sydney's Freshwater Beach, amazing locals and starting a long-term love affair with the sport in Australia.[57]

Australia entered World War I in 1914 on the side of Great Britain and 60,000 Australian troops lost their lives. The small Australian nation was deeply affected. After the war, Martin Place was selected as the site for the Sydney Cenotaph which honours the dead and remains a focus for Anzac Day commemorations in the city to this day.[58] The city's main war memorial, the Anzac War Memorial, opened in Hyde Park in 1934.[59]

In the cultural life of the city, the first Archibald Prize was awarded in 1921. Now regarded as the most important portraiture prize in Australia, it originated from a bequest from J. F. Archibald, the editor of The Bulletin, who died in 1919. Administered by the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, it is awarded for "the best portrait, preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in Art, Letters, Science or Politics."[60] Sydney's opulent Capitol Theatre opened in 1928 and after restoration in the 1990s remains one of the nation's finest auditoriums.[61]

In a Sheffield Shield cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1930, Don Bradman, a young New South Welshman of just 21 years of age, wrote his name into the record books at by smashing the previous highest batting score in first-class cricket with 452 runs not out in just 415 minutes.[62] Although Bradman would later transfer to play for South Australia, his world-beating performances provided much needed joy to Sydney-siders through the emerging Great Depression.

The Great Depression hit Sydney badly. One of the highlights of the Depression Era however, was the completion of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. The landmark which links Sydney's northern and southern shores began construction in 1924 and took 1,400 men eight years to build at a cost of £4.2 million and of steel. It carried six traffic lanes, two rail lines and two tram tracks. Sixteen workers were killed during construction. A toll was established and it cost a horse and rider three pence and a car six pence to cross the bridge. In its first year, the average annual daily traffic was around 11,000 vehicles (by the beginning of the 21st century, the figure stood at around 160,000 vehicles per day).[63]

The Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, was to open the bridge by cutting a ribbon at its southern end. However, just as Lang was about to cut the ribbon, a man in military uniform rode in on a horse, slashing the ribbon with his sword and opening the bridge in the name of the people of New South Wales before the official ceremony began. He was promptly arrested.[64] The ribbon was hurriedly retied and Lang performed the official opening ceremony. The uninvited ribbon cutter was Francis de Groot, a member of a right-wing paramilitary group called the New Guard, opposed to Lang's leftist policies and resentful of the fact that a member of the Royal Family had not been asked to open the bridge.

With large unemployment and growing state debt, the premier, Jack Lang became embroiled in disputes with the federal government and foreign creditors and was dismissed by the Governor in 1932.

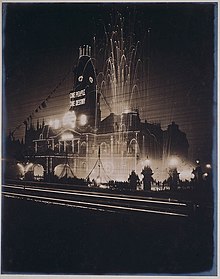

The 1938 British Empire Games were held in Sydney from 5–12 February, timed to coincide with Sydney's sesquicentennial (150 years since the foundation of British settlement in Australia).

World War II[]

On 3 September 1939 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the beginning of Australia's involvement in World War II on every national and commercial radio station across Australia. Sydney-siders fighting in the Australian Armed Forces served in campaigns against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in Europe, the Mediterranean and North Africa, as well as against Imperial Japan in south-east Asia and other parts of the Pacific.

The Japanese entered the war in December 1941. Singapore fell in February and Japan occupied much of South East Asia and the large parts of the Pacific in response, the Australian government expanded the army and air force and called for an overhaul of economic, domestic, and industrial policies to mount a total war effort.[65] Sydney saw a surge in industrial development to meet the needs of a war economy, and also the elimination of unemployment. Labour shortages forced the government to accept women in more active roles in war work.

After launching their Pacific War, the Imperial Japanese Navy managed to infiltrate New South Wales waters and in late May and early June 1942, Japanese submarines made a daring series of attacks on the cities of Sydney and Newcastle. On the night of 31 May–1 June 1942, three midget submarines were launched from their large "mother" submarines east of Sydney to enter Sydney Harbour to attack shipping located there: principally the cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra.

The first of the two-men submarines entered the harbour at 8 pm, while the third became entangled in the harbour's anti-submarine boom net. One sub managed to reach Potts Point where, under fire, it fired two torpedoes at the US heavy cruiser Chicago. Missing the target, one torpedo struck the sea wall against which the converted harbour ferry HMAS Kuttabul was moored. The blast sank the Kuttabul, killing 19 Australian and 2 British naval personnel who were asleep on board.[66]

In the aftermath of the attack, the Harbour's defences were increased and the Australian population feared Japanese invasion. Amid great controversy, the bodies of the four Japanese submariners responsible for the raid were cremated with full military honors and returned to Japan.[67] Eight days after the first attack, two large "mother" submarines lying off shore fired shells on Sydney and Newcastle. Causing little real damage, the aim of this second attack was to create a sense of unease among the city's population. Some Sydney-siders moved away from the coast while others dug air raid shelters in their backyards and membership of volunteer defence organisations grew to over 80,000.

The main Japanese naval advance towards Australian territory was however halted with the assistance of the United States Navy, in May 1942, at the Battle of the Coral Sea and by the end of 1943, the Japanese had abandoned submarine operations in Australian waters.[67]

Post war[]

Following the Second World War, the Australian government launched a largescale multicultural immigration program. Consequently, Sydney experienced population growth and increased cultural diversification throughout the post-war period.

During the post war period, Sydney enhanced its position as an education capital of the Western Pacific. Five new universities were developed to service the demands of an increasing population and demand for education: University of New South Wales, University of Technology, Sydney, University of Western Sydney and the Australian Catholic University.

Since the 1970s Sydney has undergone a rapid economic and social transformation. As aviation has replaced shipping, most new migrants to Australia have arrived in Sydney by air rather than in Melbourne by ship, and Sydney now gets the lion's share of new arrivals from every continent of the globe. As a result, the city has become one of the most multicultural in the world.

A new skyline of concrete and steel skyscrapers swept away much of the old lowrise and often sandstone skyline of early Sydney: Australia Square Tower, constructed in 1967 and designed by modernist architect Harry Seidler became a city landmark, surpassed in 1981 by Sydney Tower ("Centrepoint") as the tallest building in Sydney at 305 m. By the late 1960s, bulldozers were encroaching on The Rocks – European settlement's oldest Sydney precinct – saved only by public protests aimed at preserving 'working class housing' close to the Central Business District (which resulted also in considerable colonial era architecture being preserved in one precinct next to Circular Quay). In 1973, after a long period of planning and construction, the Sydney Opera House was officially opened. The building was from a design by Jørn Utzon. It became a symbol not only of Sydney, but of the Australian nation and was inscribed by UNESCO in 2007.[68]

As time passed, architectural modernism in Sydney has been looked at in a deplorable sense from those who wished to preserve heritage in the form of the city's most grand Victorian, Gothic, Colonial and Edwardian edifices, many of which were wiped away in the 1970s and 1980s. Architect and urban historian Singh d'Arcy writes: "From the 1950s onwards, many of Sydney's handsome sandstone and masonry buildings were wiped away by architects and developers who built brown concrete monstrosities in their place. The 1980s saw uncomfortable pastiches of facades with no coherence and little artistic merit".[69] Despite this, Sydney is still home to Australia's oldest public building, Old Government House, located in Parramatta. This building is protected by both the New South Wales State Heritage Register and Australian National Heritage List.[70][71]

Intellectuals such as those of the Sydney Push (including feminist Germaine Greer, author and broadcaster Clive James and art critic Robert Hughes) rose out of Sydney during the period, as did influential artists like painter Brett Whiteley. Paul Hogan went from painter on the Sydney Harbour Bridge to local TV star, then global film star with his hugely successful Crocodile Dundee in 1986 (a film which begins with scenes of Sydney) while theatre institutions like the Sydney Theatre Company and National Institute of Dramatic Art nurtured the budding careers of actors innumerable, some of whom forged their early careers in the city. In 1998, Fox Studios Australia opened as a major movie studio, occupying the site of the former Sydney Showground at Moore Park – going on to produce such commercially viable films as The Matrix films, Moulin Rouge!, Mission: Impossible 2 (set partly in Sydney), and the revived Star Wars and Superman film franchises. The traditional Sydney Royal Easter Show was relocated to the New Sydney Showground at Homebush.

To relieve congestion on the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Sydney Harbour Tunnel opened in August 1992. The 2.3 kilometer underwater tunnel cost A$554 million to construct. Built to withstand earthquakes and sinking ships, in the early 21st century it carries around 75,000 vehicles a day.[63]

Although generally of mild climate, in 1993–4, Sydney suffered a serious bushfire season, causing destruction even within urban areas.

Olympic City and the new millennium[]

Stadium Australia (currently also known as ANZ Stadium due to naming rights), a multi-purpose stadium located in the Sydney Olympic Park precinct of the redeveloped Homebush Bay was completed in March 1999 at a cost of A$690 million to serve as a venue for the 2000 Summer Olympics. Sydney captured global attention in the Year 2000 by hosting the Summer Olympic Games. The Opening Ceremony of the Sydney Olympics featured a theatrical rendering of Australian history through dance and a torch lighting by Aboriginal athlete Cathy Freeman. At the Closing Ceremony, President of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch, declared:[72]

"I am proud and happy to proclaim that you have presented to the world the best Olympic Games ever."

The Olympic mayor, Frank Sartor, was the Lord Mayor of Sydney, serving from 1991 to 2003 and his successor, Lucy Turnbull, became the first woman to hold that office in 2003. She was in turn succeeded by independent Clover Moore, Sydney's longest-serving mayor from 2004 – present. From 1991 to 2007, Sydneysiders governed as Prime Minister of Australia – first Paul Keating (1991–1996) and later John Howard (1996–2007), Tony Abbott (2013–2015), Malcolm Turnbull (2015–2018) and Scott Morrison (2018–present). Sydney has maintained extensive political, economic and cultural influence over Australia as well as international renown in recent decades. Following the Olympics, the city hosted the 2003 Rugby World Cup, the APEC Leaders conference of 2007 and Catholic World Youth Day 2008, led by Pope Benedict XVI.

Sydney's population officially hit 5 million people at the 2016 census.[73] The city has gained a reputation for diversity and is Australia's most multicultural city.[74] In the 2011 census, 34 percent of the population reported having been born overseas.[75] The city's first dedicated rapid transit system is currently under construction, with one line open, one under construction and two other lines announced. The project has been hailed as "transformative" by journalists.[76] Australia's first rapid transit metro line, part of the Sydney Metro, linking the suburb of Epping to the north-west of Sydney, opened on 26 May 2019. It is a first in Australian transportation, as no other Australian city currently has an automated underground metro.[77][78] The first line serves the north-western suburbs of the city, while a future line to open in 2024 will run under Sydney Harbour from the southwest into the central business district.[79] A third line, serving the western suburbs including Rozelle and Westmead, has been approved for construction.

See also[]

- Aboriginal sites of New South Wales

- Culture of Sydney

- History of Australia

- History of New South Wales

- Royal Australian Historical Society

- Rocks Push

- Sydney punchbowls

- Sydney Push

- Timeline of Sydney

References[]

- ^ Attenbrow, Val (2010). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-1-74223-116-7. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Macey, Richard (2007). "Settlers' history rewritten: go back 30,000 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (2004). A Very Short History of the World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-300559-9.

- ^ Stockton, Eugene D.; Nanson, Gerald C. (April 2004). "Cranebrook Terrace Revisited". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (1): 59–60. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2004.tb00560.x. JSTOR 40387277.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Aboriginal people and place". Sydney Barani. 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Cook's landing site". Department of the Environment. 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Aboriginal people and place".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Cook's Journal: Daily Entries, 6 May 1770". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ Rosalind Miles (2001) Who Cooked the Last Supper: The Women's History of the World Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80695-5 [1]

- ^ "Geographical Names Register Extract - Sydney". Place Name Search. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Peter Hill (2008) p.141-150

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b http://www.manly.nsw.gov.au/council/about-manly/manly-heritage--history/

- ^ "Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ Warren, Christopher (2007). "Could First Fleet Smallpox Infect Aborigines? – A Note" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 31: 152–164. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia 1780–1880, by Judy Campbell, Melbourne University Press, 2002, Foreword & pp 55, 61, 73–74, 181

- ^ "Warren-AbHist31-2007 | Smallpox | Inoculation".

- ^ Warren, Christopher (2014), "Smallpox at Sydney Cove – who, when, why?", Journal of Australian Studies, 38: 68–86, doi:10.1080/14443058.2013.849750, S2CID 143644513

- ^ "Aboriginal People of the Sydney Region". Australian Association of Bush Regenerators. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Pemulwuy: A War of Two Laws Part 1". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ Collins, David (17 May 2017). An account of the English colony in New South Wales. 2. p. 27.

- ^ Dale, David (16 February 2008). "WHO WE ARE: The man who nearly changed everything". The Sun Herald. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ J Henniker Heaton, Australian Dictionary of Dates and Men of the Time, Sydney, 1873

- ^ Al Grassby and Marji Hill, Six Australian Battlefields, North Ryde: Angus &Robertson, 1988:99.

- ^ "Pemulwuy". Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Keith Vincent Smith, "Australia's oldest murder mystery", Sydney Morning Herald 1 November 2003 accessed 26 February 2014

- ^ "Catholic Australia - Home". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "Bligh, William (1754–1817)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "Macquarie, Lachlan (1762–1824)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Postcardz, Sydney Article. 2006. History of Sydney

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Suttor, T. L. Plunkett, John Hubert (1802–1869). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Chisholm, Caroline (1808–1877)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "History of Sydney City Council" (PDF). City of Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-17. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ Hilary Golder (1995). A Short Electoral History of the Sydney City Council 1842-1992 (PDF). City of Sydney. ISBN 0-909368-93-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-17. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Events in Australian electoral history". 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019.

- ^ "QVB".

- ^ SYDNEY FEMALE REFUGE SOCIETY. (8 March 1864). Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875), p. 5. Retrieved 5 February 2019

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ australianmuseum.net.au

- ^ http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/aboutus/history

- ^ "Artists' camps | the Dictionary of Sydney".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ [2]

- ^ http://www.aagps.nsw.edu.au/

- ^ Weinberger, Eric (14 January 1996). "Where Sydney Turns Victorian". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ The 1861 Pitt Street Tramway and the Contemporary Horse Drawn Railway Proposals Wylie, R.F. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, February 1965 pp21-32

- ^ The Inauguration of Sydney's Steam Tramways Wylie, R.F. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, March 1969 pp49-59

- ^ The Cable Trams of Sydney and the Experiments Leading to Final Electrification of the Tramways Wylie, R.F. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, July/August 1974 pp145-168/190-192

- ^ The Parramatta Wharf Tramway Matthews, H.H. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, December 1958 pp181-199

- ^ "Sydney's flag and flower". City of Sydney. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "The Cenotaph - Martin Place, Sydney".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 January 2004. Retrieved 1 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "On this day in history: Sydney Harbour Bridge opens". Australian Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/ww2.asp

- ^ http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/remembering1942/midget_submarine/transcript.asp

- ^ Jump up to: a b http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/remembering1942/midget_submarine/submarine_article1.asp

- ^ "Sydney Opera House".

- ^ Butler, Katelin; Bruhn, Cameron (2017). The Apartment House. Thames & Hudson. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-500-50104-7.

- ^ "Parramatta Park and Old Government House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00596. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Old Government House and the Government Domain, O'Connell St, Parramatta, NSW, Australia (Place ID 105957)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Longman, Jere (2 October 2000). "SYDNEY 2000: CLOSING CEREMONY; A FOND FAREWELL FROM AUSTRALIA". New York Times.

- ^ "Sydney population hits 5 million". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 30 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2015–16: Media Release Sydney population hits 5 million". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 30 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Greater Sydney: Basic Community Profile" (xls). 2011 Census Community Profiles. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Mike Baird's achievements will outlive his failures". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "Hassell unveils Sydney Metro Northwest designs". The Urban Developer. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ "Premier Mike Baird reveals North West Rail Link trains will run every four minutes in peak periods". The Daily Telegraph. 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Rapid Metro build for Sydney's second subway system". governmentnews.com.au. 16 November 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

Further reading[]

- John Birmingham (1999). Leviathan: The Unauthorised Biography of Sydney. Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-184203-1.

- Charnley, W. "The Founding Of Sydney." History Today (Feb 1962), Vol. 12 Issue 2, p105-115.

- Ruth Park (1999). Ruth Park's Sydney. Duffy & Snellgrove. ISBN 978-1-875989-45-4.

Bibliography[]

External links[]

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sydney. |

- History of Sydney