Ku-ring-gai Council

| Ku-ring-gai Council New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

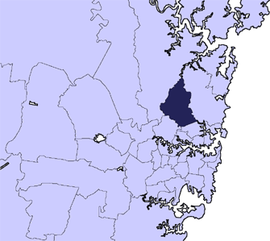

Location in Metropolitan Sydney | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°45′15″S 151°09′06″E / 33.75417°S 151.15167°ECoordinates: 33°45′15″S 151°09′06″E / 33.75417°S 151.15167°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,373/km2 (3,555/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established |

| ||||||||||||||

| Area | 86 km2 (33.2 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Mayor | Jennifer Anderson | ||||||||||||||

| Council seat | Council Chambers, Gordon | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Metropolitan Sydney | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Bradfield | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Website | Ku-ring-gai Council | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Ku-ring-gai Council is a local government area in Northern Sydney (Upper North Shore), in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The region is named after the Kuringgai tribe who once inhabited the area.

Major transport routes through the area include the Pacific Highway and North Shore railway line. Because of its good soils and elevated position as part of the Hornsby Plateau, Ku-ring-gai was originally covered by a large area of dry sclerophyll forest, parts of which still remain and form a component of the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. There are also many domestic gardens in the residential parts of Ku-ring-gai.

The Mayor of Ku-ring-gai Council is Cr. Jennifer Anderson, an independent politician. Anderson was elected to her sixth term as mayor on 17 September 2019.[3]

Ku-ring-gai is the most advantaged area in Australia to live in, at the top of the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD).[4]

Suburbs and localities in the local government area[]

Suburbs and localities serviced by Ku-ring-gai Council are:

- East Gordon

- East Killara

- East Lindfield

- East Roseville

- Fox Valley

- Gordon

- Killara

- Lindfield

- North Turramurra

- North St Ives

- North Wahroonga

- Pymble

- Roseville (Shared with Willoughby)

- Roseville Chase

- South Turramurra

- St Ives

- St Ives Chase

- Turramurra

- Wahroonga (Shared with Hornsby)

- Warrawee

- West Killara

- West Pymble

Demographics[]

At the 2016 census, there were 118,053 people in the Ku-ring-gai Council local government area, of these 48 per cent were male and 52 per cent were female. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 0.2 per cent of the population, significantly below the national average of 2.8 per cent. The median age of people in the Ku-ring-gai Council area was 41 years; slightly above the national average of 38 years. Children aged 0 – 14 years made up 20.2 per cent of the population and people aged 65 years and over made up 18.2 per cent of the population. Of people in the area aged 15 years and over, 61.3 per cent were married and 4.3 per cent were either divorced or separated; a rate that is more than half the national average.

Population growth in the Ku-ring-gai Council area between the 2001 census and the 2006 census was 0.93 per cent and in the subsequent five years to the 2011 census, population growth was 8.13 per cent. At the 2016 census, the population in the Ku-ring-gai Council area increased by 8.1 per cent. When compared with total population growth of Australia for the same period, being 8.8 per cent, population growth in the Ku-ring-gai local government area generally on par with the national average.[1] The median weekly income for residents within the Ku-ring-gai Council area was significantly higher than the national average.

At the 2016 census, the area was linguistically diverse, with Asian languages spoken in more than 18 per cent of households; more than four times the national average. Whilst the rate of all residents in the Ku-ring-gai Council area who nominated a religious affiliation with the Anglican Church has been declining over a number of census periods, the proportion during the 2016 census was 40% greater than the national average of 13.3 per cent.[1]

| Selected historical census data for Ku-ring-gai Council local government area | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census year | 2001[5] | 2006[6] | 2011[7] | 2016[1] | ||

| Population | Estimated residents on census night | 100,152 | 101,083 | 109,297 | 118,053 | |

| LGA rank in terms of size within New South Wales | 21st | |||||

| % of New South Wales population | 1.58% | |||||

| % of Australian population | 0.53% | |||||

| Cultural and language diversity | ||||||

| Ancestry, top responses |

English | 25.8% | ||||

| Australian | 21.7% | |||||

| Chinese | 8.9% | |||||

| Irish | 7.8% | |||||

| Scottish | 7.2% | |||||

| Language, top responses (other than English) |

Cantonese | 4.8% | ||||

| Mandarin | 1.7% | |||||

| Korean | 1.3% | |||||

| Persian (excluding Dari) | n/c | n/c | ||||

| Japanese | 0.9% | |||||

| Religious affiliation | ||||||

| Religious affiliation, top responses |

No religion, so described | 13.7% | ||||

| Catholic | 20.9% | |||||

| Anglican | 28.9% | |||||

| Not stated | n/c | n/c | n/c | |||

| Uniting Church | 8.7% | |||||

| Median weekly incomes | ||||||

| Personal income | Median weekly personal income | A$716 | A$814 | A$942 | ||

| % of Australian median income | 153.6% | 141.1% | 142.3% | |||

| Family income | Median weekly family income | A$2,147 | A$2,679 | A$3,046 | ||

| % of Australian median income | 209.1% | 180.9% | 175.7% | |||

| Household income | Median weekly household income | A$2,530 | A$2,508 | A$2,640 | ||

| % of Australian median income | 216.1% | 203.2% | 183.6% | |||

Council[]

Current composition and election method[]

Ku-ring-gai Council is composed of ten Councillors elected proportionally as five separate wards, each electing two Councillors. All Councillors are elected for a fixed four-year term of office, but due to delays as a result of amalgamation processes, the current term will only run for three years. The Mayor is elected bi-annually by the Councillors at the first meeting of the Council, while the Deputy Mayor is elected annually. The most recent full Council election was held on 9 September 2017, and the makeup of the Council is as follows:

The current Council, elected in 2017, in order of election by ward, is:

| Ward | Councillor | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comenarra Ward[8] | Jeff Pettett | Independent | Deputy Mayor 2018–2019[9] | |

| Callum Clarke | Independent | Deputy Mayor 2017–2018, 2019–2020[3][10] | ||

| Gordon Ward[11] | Cheryl Szatow | Independent | Mayor 2015–2016 | |

| Peter Kelly | Independent | |||

| Roseville Ward[12] | Sam Ngai | Independent | ||

| Jennifer Anderson | Independent | Mayor 2011–2012, 2013–2015, 2016–date[3] | ||

| St Ives Ward[13] | Christine Kay | Independent | ||

| Martin Smith | Independent | |||

| Wahroonga Ward[14] | Donna Greenfield | Independent | ||

| Cedric Spencer | Unaligned | Deputy Mayor 2020-date | ||

Council history[]

Ku-ring-gai was first incorporated on 6 March 1906 as the "Shire of Ku-ring-gai" and the first Shire Council was elected on 24 November 1906. The first leader of the council was elected at the first meeting on 8 December 1906, when Councillor William Cowan was elected as Shire President. There would not be a Deputy President until the council election on 1 March 1920.

On 22 September 1928, the Shire of Ku-ring-gai was proclaimed as the "Municipality of Ku-ring-gai" and the titles of 'Shire President' and 'Councillor' were retitled to be 'Mayor' and 'Alderman' respectively. In 1993, with the passing of a new Local Government Act, council was retitled as simply "Ku-ring-gai Council" and Aldermen were retitled as Councillors.[15]

A 2015 review of local government boundaries by the NSW Government Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal recommended that Ku-ring-gai Council and parts of the Hornsby Shire north of the M2 merge to form a new council with an area of 540 square kilometres (210 sq mi) and support a population of approximately 270,000.[16] The Ku-ring-gai Council took the NSW Government to court and, on appeal, the NSW Court of Appeal found that the Council had been denied procedural fairness. The proposed merger was stood aside indefinitely.[17] In July 2017, the Berejiklian government decided to abandon the forced merger of the Hornsby and Ku-ring-gai local government areas, along with several other proposed forced mergers.[18]

Planning and development[]

During the term of former Planning Minister, Frank Sartor, planning law reforms were passed that gave development approval to a panel and away from local government. These new laws were controversially implemented in Ku-ring-gai, with immense opposition from the local population who claim that their suburbs, with nationally recognised heritage values in both housing and original native forest, are being trashed by slab-sided apartment developments with no effective protection provided by either the Ku-ring-gai Council or the State Government. This has been termed "The Rape of Ku-ring-gai".[19]

The laws are intended to take development approval power away from local councils and to the Planning NSW, via the development panels. Planning panels are about to be introduced across New South Wales under recently passed planning reforms. In 2005-06, Ku-ring-gai had the second highest reported total development value in the state - A$1.7 billion, more than Parramatta, second only to the City of Sydney.

Shire Clerks, Town Clerks and General Managers[]

| Name | Term | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Edward Astley | 21 June 1906 – 31 August 1911 | [20][21] |

| James A. Gilroy | 1 September 1911 – March 1925 | [22] |

| Arthur Havelock Hirst | March 1925 – 18 November 1947 | [23] |

| Norman L. Griffiths | 18 November 1947 – 22 September 1969 | |

| Frederick E. Newton | 22 September 1969 – 5 October 1970 | |

| Graham Joss | 5 October 1970 – 16 August 1971 | |

| Lyndhurst Evelyn Whalan | 16 August 1971 – 12 November 1973 | |

| Warren Taylor | 12 November 1973 – 1993 | [24] |

| Joseph Robert Diffen | 1993–1997 | [25] |

| Rhonda Bignell | 1997–2002 | |

| Brian Bell | 2002 – February 2006 | [26][27] |

| John McKee | 1 March 2006 – present | [28] |

Heritage listings[]

Ku-ring-gai Council has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Gordon, 17 McIntosh Street: Eryldene, Gordon[29]

- Gordon, Middlemiss Street: Gordon railway station, Sydney[30]

- Gordon, 691 Pacific Highway: Iolanthe, Gordon[31]

- Gordon, 707 Pacific Highway: Tulkiyan[32]

- Gordon, 799 Pacific Highway: Gordon Public School (former)[33]

- Killara, 13 Kalang Avenue: Harry and Penelope Seidler House[34]

- Killara, 1 Werona Avenue: Woodlands, Killara[35]

- Lindfield, 33 Tryon Road: Tryon Road Uniting Church[36]

- Pymble, Pacific Highway: Pymble Reservoirs No. 1 and No. 2[37][38]

- Pymble, 982-984 Pacific Highway: Pymble Substation[39]

- Pymble, 29 Telegraph Road: Eric Pratten House[40]

- Turramurra, 17 Boomerang Street: Ingleholme[41]

- Turramurra, 43 Ku-Ring-Gai Avenue: Cossington (Turramurra)[42]

- Wahroonga, 62 Boundary Road: Jack House, Wahroonga[43]

- Wahroonga, 69-71 Clissold Road: Rose Seidler House[44]

- Wahroonga, 61-65 Coonanbarra Road: St John's Uniting Church, Wahroonga[45]

- Wahroonga, 16 Fox Valley Road: Purulia, Wahroonga[46]

- Wahroonga, 69 Junction Road: Evatt House[47]

- Wahroonga, North Shore railway: Wahroonga railway station[48]

- Wahroonga, 1526 Pacific Highway: Mahratta, Wahroonga[49]

- Wahroonga, 1678 Pacific Highway and Woonona Avenue: Wahroonga Reservoir[50]

- Wahroonga, 23 Roland Avenue: Simpson-Lee House I[51]

- Wahroonga, 14 Woonona Avenue: The Briars, Wahroonga[52]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Ku-ring-gai (A)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017-18". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019. Estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McCallum, Jake (22 September 2017). "Councillor Jennifer Anderson re-elected as Ku-ring-gai Mayor following contentious vote". Hornsby Advocate. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Gladstone, Nigel (27 March 2018). "Sydney's latte line exposes a city divided". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (9 March 2006). "Ku-ring-gai (A)". 2001 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Ku-ring-gai (A)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Ku-ring-gai (A)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai - Comenarra Ward". NSW Local Council Elections 2017. NSW Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai Council elects new Deputy Mayor" (Media Release). Ku-ring-gai Council. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "Councillor Jennifer Anderson elected for an historic sixth term as Mayor" (Media Release). Latest news - media releases. Ku-ring-gai Council. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai - Gordon Ward". NSW Local Council Elections 2017. NSW Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai - Roseville Ward". NSW Local Council Elections 2017. NSW Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai - St Ives Ward". NSW Local Council Elections 2017. NSW Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Ku-ring-gai - Wahroonga Ward". NSW Local Council Elections 2017. NSW Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Curby, Pauline; Macleod, Virginia (2006). Under the Canopy: A Centenary History of Ku-ring-gai Council. Gordon, NSW: Ku-ring-gai Council. p. 207. ISBN 097754740X.

- ^ "Merger proposal: Hornsby Shire Council (part), Ku-ring-gai Council" (PDF). Government of New South Wales. January 2016. p. 7. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Munro Kelsey (28 April 2017). "NSW government fails to appeal Ku-ring-gai Council amalgamation court loss". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ Blumer, Clare; Chettle, Nicole (27 July 2017). "NSW council amalgamations: Mayors fight to claw back court dollars after backflip on merger". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ Demspter, Quentin (15 August 2008). "The "Rape" of Ku-ring-gai" (Transcript). Stateline. Australia: ABC TV. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "KURING-GAI SHIRE COUNCIL". The Daily Telegraph (8443). New South Wales, Australia. 25 June 1906. p. 3. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PERSONAL". Wagga Wagga Express. 52 (9129). New South Wales, Australia. 9 November 1911. p. 5. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PERSONAL". Daily Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 27 November 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Town Clerk Charged With Theft". The Sun (11, 648). New South Wales, Australia. 26 May 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "KU-RING-GAI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL.—RESIDENTIAL". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (163). New South Wales, Australia. 28 December 1973. p. 5606. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "KU-RING-GAI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (26). New South Wales, Australia. 1 March 1996. p. 997. Retrieved 20 September 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New GM named for Lake Macquarie council". ABC News. 9 December 2005. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Fifty years in local government". Local Government Focus. July 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "General Manager: John McKee". Civic Management. Ku-ring-gai Council. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Eryldene". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00019. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Gordon Railway Station". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01150. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Iolanthe". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00227. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Tulkiyan". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01733. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Gordon Public School". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00757. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Harry and Penelope Seidler House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01793. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Woodlands". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01762. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Tryon Road Uniting Church". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01672. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Pymble Reservoir No.1 (Covered) (WS 0097)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01632. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Pymble Reservoir No.2 (Covered) (WS 0098)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01633. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Substation". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00940. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Eric Pratten House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01443. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Ingleholme & Garage". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00071. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Cossington". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01763. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Jack House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01910. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Rose Seidler House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00261. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "St. John's Uniting Church, Hall and Manse". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01670. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Purulia". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00184. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Evatt House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01711. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Wahroonga Railway Station group". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01280. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Mahratta and Site". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00708. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Wahroonga Reservoir (Elevated) (WS 0124)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01352. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Simpson-Lee House I". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01800. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Briars, The". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00274. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

External links[]

- Ku-ring-gai Council

- Local government areas in Sydney

- 1906 establishments in Australia