Republicanism in the United Kingdom

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

| Politics portal |

Republicanism in the United Kingdom is the political movement that seeks to replace the United Kingdom's monarchy with a republic. Supporters of the movement, called republicans, support alternative forms of governance to a monarchy, such as an elected head of state, or no head of state at all.

Monarchy has been the form of government used in the countries that now make up the United Kingdom almost exclusively since the Middle Ages. A republican government existed in England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, in the mid-17th century as a result of the Parliamentarian victory in the English Civil War. The Commonwealth of England, as the period was called, lasted from the execution of Charles I in 1649 until the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Context[]

In Britain, republican sentiment has largely focused on the abolition of the British monarch, rather than the dissolution of the British Union or independence for its constituent countries. In Northern Ireland, the term "republican" is usually used in the sense of Irish republicanism. While also against the monarchy, Irish republicans are against the presence of the British state in any form in Ireland and advocate creating a united Ireland, an all-island state comprising the whole of Ireland. Unionists who support a British republic also exist in Northern Ireland.

There are republican members of the Scottish National Party (SNP) in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales who advocate independence for those countries as republics. The SNP's official policy is that the British monarch would remain head of state of an independent Scotland, unless the people of Scotland decided otherwise.[1] Plaid Cymru have a similar view for Wales, although its youth wing, Plaid Ifanc, has an official policy advocating a Welsh republic.[citation needed] The Scottish Socialist Party and the Scottish Greens both support an independent Scottish republic.

History[]

Since the 1970s, early modern English republicanism has been extensively studied by historians. James Harrington (1611–1677) is generally considered to be the most representative republican writer of the era.[2]

Commonwealth of England[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

The countries that now make up the United Kingdom, together with the Republic of Ireland, were briefly ruled as a republic in the 17th century, first under the Commonwealth consisting of the Rump Parliament and the Council of State (1649–1653) and then under the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell and later his son Richard (1658–1659), and finally under the restored Rump Parliament (1659–1660). The Commonwealth Parliament represented itself as a republic in the classical model, with John Milton writing an early defence of republicanism in the idiom of constitutional limits on a monarch's power.[citation needed] Cromwell's Protectorate was less ideologically republican and was seen by Cromwell as restoring the mixed constitution of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy found in classical literature and English common law discourse.[citation needed]

First the Kingdom of England was declared to be the Commonwealth of England and then Scotland and Ireland were briefly forced into union with England by the army. This decision was later reversed when the monarchy was restored in 1660. In 1707 the Act of Union between England and Scotland was signed; the two countries' parliaments became one, and in return Scotland was granted access to the English overseas possessions.[citation needed]

Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax were often ruthless in putting down the mutinies which occurred within their own army towards the end of the civil wars (prompted by Parliament's failure to pay the troops). They showed little sympathy for the Levellers, an egalitarian movement which had contributed greatly[citation needed] to Parliament's cause but sought representation for ordinary citizens. The Leveller point of view had been strongly represented in the Putney Debates, held between the various factions of the army in 1647, just prior to the king's temporary escape from army custody. Cromwell and the grandees were not prepared to permit such a radical democracy and used the debates to play for time while the future of the King was being determined. Catholics were persecuted zealously under Cromwell.[citation needed] [3]Although he personally was in favour of religious toleration – "liberty for tender consciences" – not all his compatriots agreed. The war led to much death and chaos in Ireland where Irish Catholics and Protestants who fought for the Royalists were persecuted. There was a ban on many forms of entertainment, as public meetings could be used as a cover for conspirators; horse racing was banned, the maypoles were famously cut down, the theatres were closed, and Christmas celebrations were outlawed for being too ceremonial, Catholic, and "popish".[citation needed]

Much of Cromwell's power was due to the Rump Parliament, a Parliament purged of opposition to grandees in the New Model Army. Whereas Charles I had been in part restrained by a Parliament that would not always do as he wished (the cause of the civil war), Cromwell was able to wield much more power as only loyalists were allowed to become MPs, turning the chamber into a rubber-stamping organisation. This was ironic given his complaints about Charles I acting without heeding the "wishes" of the people. Even so, he found it almost impossible to get his Parliaments to follow all his wishes. His executive decisions were often thwarted, most famously in the ending of the rule of the regional major generals appointed by himself.[citation needed]

In 1657 Cromwell was offered the crown by Parliament, presenting him with a dilemma since he had played a great role in abolishing the monarchy. After two months of deliberation, he rejected the offer. Instead, he was ceremonially re-installed as Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland (Wales was a part of England), with greater powers than he had previously held. It is often suggested that offering Cromwell the crown was an effort to curb his power: as a king he would be obliged to honour agreements such as Magna Carta, but under the arrangement he had designed he had no such restraints. This allowed him to preserve and enhance his power and the army's while decreasing Parliament's control over him, probably to enable him to maintain a well-funded army which Parliament could not be depended upon to provide.[citation needed]

The office of Lord Protector was not formally hereditary, although Cromwell was able to nominate his own successor in his son, Richard.[citation needed]

Restoration of the monarchy[]

Although England, Scotland and Ireland became constitutional monarchies, after the reigns of Charles II and his brother James II and VII, and with the ascension of William III and Mary II to the English, Irish and Scottish thrones as a result of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, there have been movements throughout the last few centuries whose aims were to remove the monarchy and establish a republican system. A notable period was the time in the late 18th century and early 19th century when many Radicals such as the minister Joseph Fawcett were openly republican.[4]

American and French Revolutions[]

The American Revolution had a great impact on political thought in Ireland and Britain. According to Christopher Hitchens, the British–American author, philosopher, politician and activist, Thomas Paine was the "moral author of the American Revolution", who posited in the soon widely read pamphlet Common Sense (January 1776) that the conflict of the Thirteen Colonies with the Hanoverian monarchy in London was best resolved by setting up a separate democratic republic.[6] To him, republicanism was more important than independence. However, the circumstances forced the American revolutionaries to give up any hope of reconciliation with Britain, and reforming its 'corrupt' monarchial government, that so often dragged the American colonies in its European wars, from within.[5] He and other British republican writers saw in the Declaration of Independence (4 July 1776) a legitimate struggle against the Crown, that violated people's freedom and rights, and denied them representation in politics.[7]

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, debates started in the British Isles on how to respond. Soon a pro-Revolutionary republican and anti-Revolutionary monarchist camp had established themselves amongst the intelligentsia, who waged a pamphlet war until 1795. Prominent figures of the republican camp were Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin and Paine.[8]

Paine would also play an important role inside the revolution in France as an elected member of the National Convention (1792–3), where he lobbied for an invasion of Britain to establish a republic after the example of the United States, France and its Sister Republics, but also opposed the execution of Louis XVI, which got him arrested.[6] The First French Republic would indeed stage an Expedition to Ireland in December 1796 to help the Society of United Irishmen set up an Irish republic in order to destabilise the United Kingdom, but this ended in a failure. The subsequent Irish Rebellion of 1798 was utterly crushed by the British Army. Napoleon also planned an invasion of Britain since 1798 and more seriously since 1803, but in 1804 he relinquished republicanism by crowning himself Emperor of the French and converting all Sister Republics into client kingdoms of the French Empire, before calling off the invasion of Britain altogether in 1805.[citation needed]

Revolutionary republicanism, 1800–1848[]

From the start of the French Revolution into the early 19th century, the revolutionary blue-white-red tricolour was used throughout England, Wales and Ireland in defiance of the royal establishment. During the 1816 Spa Fields riots, a green, white and red horizontal flag appeared for the first time, soon followed by a red, white and green horizontal version allegedly in use during the 1817 Pentrich rising and the 1819 Peterloo Massacre. The latter is now associated with Hungary, but then it became known as the . It may have been inspired by the French revolutionary tricolour, but this is unclear. It was however often accompanied by slogans consisting of three words such as "Fraternity – Liberty – Humanity" (a clear reference to Liberté, égalité, fraternité), and adopted by the Chartist movement in the 1830s.[9]

Besides these skirmishes in Great Britain itself, separatist republican revolutions against the British monarchy during the Canadian rebellions of 1837–38 and the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848 failed.

Parliament passed the Treason Felony Act in 1848. This act made advocacy of republicanism punishable by transportation to Australia, which was later amended to life imprisonment. The law is still on the statute books; however in a 2003 case, the Law Lords stated that "It is plain as a pike staff to the respondents and everyone else that no one who advocates the peaceful abolition of the monarchy and its replacement by a republican form of government is at any risk of prosecution", for the reason that the Human Rights Act 1998 would require the 1848 Act to be interpreted in such a way as to render such conduct non-criminal.[10]

Late 19th century[]

During the later years of Queen Victoria's reign, there was considerable criticism of her decision to withdraw from public life following the death of her husband, Prince Albert. This resulted in a "significant incarnation" of republicanism.[11] During the 1870s, calls for Britain to become a republic on the American or French model were made by the politicians Charles Dilke[12] and Charles Bradlaugh, as well as journalist George W. M. Reynolds.[11] This republican presence continued in debates and the Labour press, especially in the event of royal weddings, jubilees and births, until well into the Interwar Period.[11]

Some members of the Labour Party, such as Keir Hardie (1856–1915), also held republican views.[13]

20th-century republicanism[]

In 1923, at the Labour Party's annual conference, two motions were proposed, supported by Ernest Thurtle and Emrys Hughes. The first was "that the Royal Family is no longer a necessary party of the British constitution", and the second was "that the hereditary principle in the British Constitution be abolished".[14] George Lansbury responded that, although he too was a republican, he regarded the issue of the monarchy as a "distraction" from more important issues. Lansbury added that he believed the "social revolution" would eventually remove the monarchy peacefully in the future. Both of the motions were overwhelmingly defeated.[14][15][16] Following this event, most of the Labour Party moved away from advocating republican views.[14] In 1936, following the abdication of Edward VIII, MP James Maxton proposed a "republican amendment" to the Abdication Bill, which would have established a Republic in Britain. Maxton argued that while the monarchy had benefited Britain in the past, it had now "outlived its usefulness". Five MPs voted to support the bill, including Alfred Salter. However the bill was defeated by 403 votes.[17][18]

Willie Hamilton, a republican Scottish Labour MP who served from 1950 to 1987, was known for his outspoken anti-royal views. He discussed these at length in his 1975 book My Queen and I.[19]

In 1991, Labour MP Tony Benn introduced the Commonwealth of Britain Bill, which called for the transformation of the United Kingdom into a "democratic, federal and secular Commonwealth of Britain", with an elected president.[20] The monarchy would be abolished and replaced by a republic with a written constitution. It was read in Parliament a number of times until his retirement at the 2001 election, but never achieved a second reading.[21] Benn presented an account of his proposal in Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain.[22]

In January 1997, ITV broadcast a live television debate Monarchy: The Nation Decides, in which 2.5 million viewers voted on the question "Do you want a monarch?" by telephone. Speaking for the republican view were Professor Stephen Haseler, (chairman of Republic), agony aunt Claire Rayner, Paul Flynn, Labour MP for Newport West and Andrew Neil, then the former editor of The Sunday Times. Those in favour of the monarchy included author Frederick Forsyth, Bernie Grant, Labour MP for Tottenham, and Jeffrey Archer, former deputy chairman of the Conservative Party. Conservative MP Steven Norris was scheduled to appear in a discussion towards the end of the programme, but officials from Carlton Television said he had left without explanation. The debate was conducted in front of an audience of 3,000 at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham, with the telephone poll result being that 66% of voters wanted a monarch, and 34% did not.[23]

At the annual State Opening of Parliament, MPs are summoned to the House of Lords for the Queen's Speech. From the 1990s until the 2010s, republican MP Dennis Skinner regularly made a retort to Black Rod, the official who commands the House of Commons to attend the speech.[24] Skinner had previously remained in the Commons for the speech.[25]

21st-century republicanism[]

MORI polls in the opening years of the 21st century showed support for retaining the monarchy stable at around 70% of people, but in 2005, at the time of the wedding of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles, support for the monarchy dipped, with one poll showing that 65% of people would support keeping the monarchy if there were a referendum on the issue, with 22% saying they favoured a republic.[26] In 2009 an ICM poll, commissioned by the BBC, found that 76% of those asked wanted the monarchy to continue after the Queen, against 18% of people who said they would favour Britain becoming a republic and 6% who said they did not know.[27]

In February 2011, a YouGov poll put support for ending the monarchy after the Queen's death at 13%, if Prince Charles becomes King.[28] However, an ICM poll shortly before the royal wedding suggested that 26% thought Britain would be better off without the monarchy, with only 37% "genuinely interested and excited" by the wedding.[29] In April 2011, in the lead up to the Royal Wedding, an Ipsos MORI poll of 1,000 British adults found that 75% of the public would like Britain to remain a monarchy, with 18% in favour of Britain becoming a republic. In May 2012, in the lead up to the Queen's Diamond Jubilee, an Ipsos MORI poll of 1,006 British adults found that 80% were in favour of the monarchy, with 13% in favour of the United Kingdom becoming a republic. This was thought to be a record high figure in recent years in favour of the monarchy.[26]

The main organisation campaigning for a republic in the United Kingdom is the campaign group Republic. Formed in 1983, Republic is frequently cited by much of the UK media on issues involving the royal family.[30][31][failed verification]

In September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn, a Labour MP with republican views, won his party's leadership election and became both Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party. In 1991, Corbyn had seconded the Commonwealth of Britain Bill.[20] However, Corbyn stated during his 2015 campaign for the leadership that republicanism was "not a battle that I am fighting".[32][33]

At the swearing of oaths in the Commons following the 2017 general election, Republic reported that several MPs had prefixed their parliamentary oath of allegiance with broadly republican sentiments, such as a statement referring to their constituents, rather than the Queen. If an MP does not take the oath or the affirmation to the Queen, they will not be able to take part in parliamentary proceedings or paid any salary and allowances until they have done so. Such MPs included: Richard Burgon, Laura Pidcock, Dennis Skinner, Chris Williamson, Paul Flynn, Jeff Smith, and Emma Dent Coad. Roger Godsiff and Alex Sobel also expressed sympathy for an oath to their constituents.[34]

In May 2021, a YouGov poll put support for the monarchy down at 61% (with 24% against) among over-18s, with a particularly high rise in republican views and an overall plurality for its replacement with an elected head of state in the 18–24 age group (41%–31%).[35] The poll also suggested significant reductions in support for the monarchy in 25–49 year olds, and a slight fall in support among over 65s.

Supporters[]

A number of prominent individuals in the United Kingdom advocate republicanism.

Political parties[]

As of 2021, none of the four major British political parties—the Labour Party, the Conservative Party, the Liberal Democrats, and the SNP—have an official policy of republicanism. However, there are a number of individual politicians who favour abolition of the monarchy.

The Green Party of England and Wales, with one MP in Parliament since 2010, has an official policy of republicanism.[36] The Irish republican party Sinn Féin has seven MPs, but they do not take their UK parliamentary seats.[37] The Scottish Green Party, with eight MSPs in the 2021–2026 Scottish Parliament, supports having an elected head of state in an independent Scotland.[38]

Labour for a Republic is a republican pressure group of Labour party members and supporters,[39] founded by Labour politician Ken Ritchie in May 2011. It held its first meeting in 2012. Efforts to get the campaign started were then unsuccessful.[40][41] It has since held fringe meetings, and other informal meetings, and appeared in the media on a few occasions.

Republic (lobby group)[]

The largest lobby group in favour of republicanism in the United Kingdom is the Republic campaign group, founded in 1983. The group has benefited from occasional negative publicity about the Royal Family, and Republic reported a large rise in membership following the wedding of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles. Republic has lobbied on changes to the parliamentary oath of allegiance, royal finances and changes to the Freedom of Information Act relating to the monarchy, none of which have produced any change. However, Republic has been invited to Parliament to talk as witnesses on certain issues related to the monarchy such as conduct of the honours system in the United Kingdom.

In 2009 Republic made news[42] by reporting Prince Charles's architecture charity to the Charity Commission, claiming that the Prince was effectively using the organisation as a private lobbying firm (the Commission declined to take the matter further). Republic has previously broken stories about royals using the Freedom of Information Act. The organisation is regularly called up to comment and provide quotes for the press, national and local radio and national TV programmes, with much criticism as to the portrayal of the monarchy by the BBC which has been accused of celebrating the monarchy rather than keeping its politically neutral stance on issues related to it.

Media[]

The Guardian, Observer and Independent newspapers have all advocated the abolition of the monarchy.[43] In the wake of the 2009 MPs' expenses scandal, a poll of readers of the Guardian and Observer newspapers placed support for abolition of the monarchy at 54%, although only 3% saw it as a top priority.[44]

Opinion polling[]

Graphical summary[]

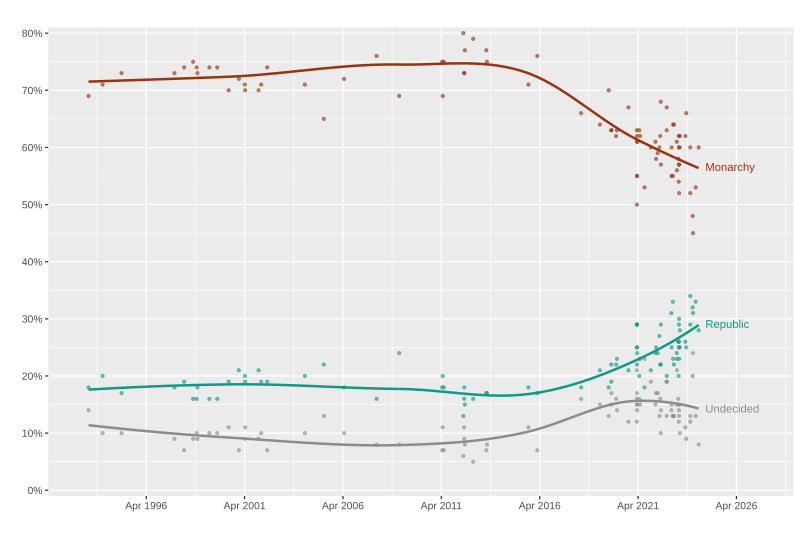

The chart below shows opinion polls conducted about whether the United Kingdom should become a republic. The trend lines are local regressions (LOESS).

Poll results[]

Various questions have been asked by opinion polling companies. The following table includes a selection of polls of the general public summarised by whether respondents support the continuation of the monarchy or its abolition (whether or not a republic is specified). Polling suggests that a large majority of Britons were in favour of the monarchy during the 1990s and 2000s with support mostly ranging from 70% to 74% and never falling below 65%. Support appeared to strengthen in the early to mid 2010s with most polls during this period suggesting that between 75% and 80% (and all suggesting at least 69%) of the public were in favour of the monarchy. However, enthusiasm for the institution seems to have dampened in recent years with polls since 2019 suggesting it maintains majority but less unanimous support of between 50% and 67%. Polls since the 1990s have shown the proportion favouring a republic as ranging from 13% to 29% but have generally indicated the figure rests at around one fifth of the population.

| Dates conducted | Polling organisation | Client | Sample size | Monarchy | Republic | Undecided[a] | Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 July 2021 | Redfield and Wilton Strategies | New Statesman | 1,500 | 53% | 18% | 23% | N\A (responders were asked whether they supported or opposed the monarchy) |

| 12 March–7 May 2021 | YouGov | N/A | 4,997 | 61% | 24% | 15% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 21–22 April 2021 | YouGov | The Times | 1,730 | 63% | 20% | 16% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 11–12 March 2021 | Opinium | The Observer | 2,001 | 55% | 29% | 17% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or Britain become a republic? |

| 9–10 March 2021 | Survation | Sunday Mirror | 958 | 55% | 29% | 16% | If there were a referendum tomorrow with the question:“Should the United Kingdom remain a constitutional monarchy with the Monarch as head of state, or become a republic with a President as head of state?” How would you vote?[b] |

| 9 March 2021 | J.L. Partners | Daily Mail | 1,056 | 50% | 29% | 21% | Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? The monarchy should be abolished. |

| 8–9 March 2021 | YouGov | N/A | 1,672 | 63% | 25% | 12% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 2–4 October 2020 | YouGov | N/A | 1,626 | 67% | 21% | 12% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 18 February 2020 | YouGov | N/A | 3,142 | 62% | 22% | 16% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy, or not? |

| 21–22 November 2019 | YouGov | The Sunday Times | 1,677 | 63% | 19% | 17% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 13–16 February 2016 | Ipsos MORI | King's College London | 1,000 | 76% | 17% | 7% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 3–4 September 2015 | YouGov | N/A | 1,579 | 71% | 18% | 11% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 13–15 July 2013 | Ipsos MORI | N/A | 1,000 | 77% | 17% | 6% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 10–13 November 2012 | Ipsos MORI | King's College London | 1,014 | 79% | 16% | 5% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 9–11 June 2012 | Ipsos MORI | N/A | 1,016 | 77% | 15% | 8% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 27–28 May 2012 | YouGov | N/A | 1,743 | 73% | 16% | 11% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 12–14 May 2012 | Ipsos MORI | N/A | 1,006 | 80% | 13% | 6% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 26–27 April 2011 | YouGov | Cambridge University | ? | 69% | 20% | 11% | Do you think Britain should continue to have a monarchy in the future, or should it be replaced with an elected head of state? |

| 15–17 April 2011 | Ipsos MORI | Reuters | 1,000 | 75% | 18% | 7% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 20–22 April 2006 | Ipsos MORI | The Sun | 1,006 | 72% | 18% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 7–9 April 2005 | MORI | The Observer/Sunday Mirror | 1,004 | 65% | 22% | 13% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 23–25 April 2004 | MORI | N/A | c. 1000[c] | 71% | 20% | 10% | Do you favour Britain electing its Head of State or do you favour Britain retaining the monarchy? |

| 24–26 May 2002 | MORI | Tonight with Trevor McDonald | 1,002[c] | 74% | 19% | 7% | If there was a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 1–3 February 2002 | MORI | N/A | ?[c] | 71% | 19% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 14–16 December 2001 | MORI | N/A | 1,000[c] | 70% | 21% | 9% | If there was a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 10–12 April 2001 | MORI | Daily Mail | 1,003 | 70% | 19% | 11% | If there were a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 5–6 April 2001 | MORI | The Mail on Sunday | 814 | 71% | 20% | 9% | If there were a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 29 December 2000 | MORI | The Mail on Sunday | 504 | 73% | 15% | 12% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 13–15 December 2000 | MORI | News of the World | 621 | 72% | 21% | 7% | If there were a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 8–9 June 2000 | MORI | Sunday Telegraph | 621 | 70% | 19% | 11% | If there were a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 8–10 November 1999 | MORI | Daily Mail | 1,019 | 74% | 16% | 10% | If there were a referendum on the issue, would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 15–16 June 1999 | MORI | The Sun | 806 | 74% | 16% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 5–6 November 1998 | MORI | Daily Mail/GMTV | 1,019 | 73% | 18% | 9% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 23–24 October 1998 | MORI | The Sun | 600 | 74% | 16% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 18–20 August 1998 | MORI | The Mail on Sunday | 804 | 75% | 16% | 9% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 5–8 March 1998 | MORI | The Sun | 1,000 | 74% | 19% | 7% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 6–7 September 1997 | MORI | The Sun | 602 | 73% | 18% | 9% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 28–29 December 1994 | MORI | ? | ? | 73% | 17% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 7–12 January 1994 | MORI | ? | ? | 71% | 20% | 10% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

| 22–26 April 1993 | MORI | ? | ? | 69% | 18% | 14% | Would you favour Britain becoming a republic or remaining a monarchy? |

Notes[]

Arguments[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

The public debate around republicanism has centred around the core republican argument that a republic is more democratic and compatible with the notion of popular sovereignty. The advocacy group Republic argues:

The monarchy is not only an unaccountable and expensive institution, unrepresentative of modern Britain, it also gives politicians almost limitless power. It does this is in a variety of ways:

- Royal Prerogative: Royal powers that allow the Prime Minister to declare war or sign treaties (amongst other things) without a vote in Parliament.

- The Privy Council: A body of advisors to the monarch, now mostly made up of senior politicians, which can enact legislation without a vote in Parliament.

- The Crown-in-Parliament: The principle, which came about when Parliament removed much of the monarch's power, by which Parliament can pass any law it likes – meaning our liberties can never be guaranteed.[45]

The core anti-republican defense is that there is nothing in a republic that is inherently more democratic compared to a constitutional monarchy when both forms of government are based on parliamentarianism and constitutionalism, and that traditional institutions have confirmed the citizens as sovereign beings.

In favour of a republic

- More democratic: Republicans argue that monarchy devalues a parliamentary system insofar monarchical prerogative powers can be used to circumvent normal democratic process with no accountability, and such processes are more desirable than not for any given nation-state.[45]

It is further argued that monarchy contradicts democracy insofar it denies the people a basic right: Republicans believe that it should be a fundamental right of the people of any nation to elect their head of state and for every citizen to be eligible to hold that office. It is argued such a head of state is more accountable to the people, and that such accountability to the people creates a better nation.[46][47]

- Fairer and less elitist; does not demand deference: Republicans assert that hereditary monarchy is unfair and elitist. They claim that in a modern and democratic society no one should be expected to defer to another simply because of their birth. It is argued that the way citizens are expected to address members, however junior, of the royal family is part of an attempt to keep subjects "in their place".[48] Such a system, they assert, does not make for a society which is at ease with itself, and it encourages attitudes which are more suited to a bygone age of imperialism than to a "modern nation". Some claim that maintaining a privileged royal family diminishes a society and encourages a feeling of dependency in many people who should instead have confidence in themselves and their fellow citizens.[47] Further, republicans argue that "the people", not the members of one family, should be sovereign.[47]

- Based on merit and arouses aspiration: The order of succession in a monarchy specifies a person who will become head of state, regardless of qualifications. The highest titular office in the land is not open to "free and fair competition". Although monarchists argue that the position of Prime Minister, the title with real power, is something anyone can aspire to become, the executive and symbolically powerful position of Head of State is not.

Further, republicans argue that members of the royal family bolster their position with unearned symbols of achievement. Examples in the UK include Elizabeth II's honorary military positions as colonel-in-chief, irrespective of her military experience. There is debate over the roles which the members of the monarchy have played in the military; many doubt that members of the Royal Family have served on the front line on the same basis as other members of the Armed Forces. Examples here include Prince Andrew, whose presence during the Falklands War was later criticised by the commander of the British Naval Force who stated that "special measures" had to be taken to ensure that the prince did not lose his life.[49] It is seen to some as more of a PR exercise than military service.[50]

- Compatible with a multiracial and multicultural society: Peter Tatchell has argued that the institution of monarchy in the UK is inherently racist as there have, and likely will only ever be, white monarchs. As a result, the institution cannot provide the same opportunity as with a republic to have a citizen of any background in the role of Head of State.[51]

- Does not impose a state religion: The Church of England is an established church, and the British Sovereign is the titular Supreme Governor. The church is tax exempt and provides the House of Lords in Parliament with 26 unelected bishops as its representatives. Republicans argue that a monarch who is the head of an established church in an increasingly secular and multicultural society reinforces the notion of hereditary privilege based on the divine right of kings.[citation needed] On the royal coat of arms is the motto in French: Dieu et mon droit (God and my right).

- Does less harm to those who would be monarchs: Republicans argue that a hereditary system condemns each heir to the throne to an abnormal childhood. This was historically the reason why the anarchist William Godwin opposed the monarchy. Johann Hari has written a book God Save the Queen? in which he argues that every member of the royal family has suffered psychologically from the system of monarchy.[52]

- Favours accountability and impartiality: Republicans argue that monarchs are not impartial but harbour their own opinions, motives, and wish to protect their interests. Republicans claim that monarchs are not accountable. As an example, republicans argue that Prince Charles has spoken and acted in ways that have widely been interpreted as taking a political stance, citing his refusal to attend, in protest of China's dealings with Tibet, a state dinner hosted by the Queen for the Chinese head of state; his strong stance on GM food; and the contents of the black spider memos, which were released following freedom of information litigation, regarding how people achieve their positions.[53][54][55]

- Costs less: Republicans claim that the total costs to taxpayers including hidden elements (e.g., the Royal Protection security bill and lost rental income from palaces and state-owned land) of the monarchy are £334 million per annum.[56] The Daily Telegraph claims the monarchy costs each adult in the UK around £62 a year.[57] Republicans also argue that the Royal finances, which are exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, are shrouded in secrecy and should be subject to greater scrutiny. Although monarchists argue that this does not take into account the "hereditary revenues" which generated £190.8 million for the treasury in 2007–2008, the advocacy group Republic assert that the Crown Estate, from which these revenues are derived, is national and State property, and that the monarch cannot surrender what they have never owned.[58] The monarchy is estimated to cost British taxpayers £202.4 million, when costs such as security are included, making it the most expensive monarchy in Europe and 112 times more expensive than the presidency of the Republic of Ireland.[58]

In favour of a constitutional monarchy

- Not inherently undemocratic: Opponents of the republican movement argue that the current system is still democratic as the Government and MPs of Parliament are elected by universal suffrage and as the Crown acts only on the advice of the Parliament, the people still hold power. Monarchy only refers to how the head of state is chosen and not how the Government is chosen. It is only undemocratic if the monarchy holds meaningful power, which it currently does not as government rests with Parliament.

(However, it was revealed in October 2011 that both the Queen and the Prince of Wales do have the power to veto government legislation which affects their private interests.[61] The Queen attended a cabinet meeting as an observer on 18 December 2012 – the first Monarch to have done so since George III in 1781.)[62]

- Safeguards the constitutional rights of the individual: The British constitutional system sets limits on Parliament and separates the executive from direct control over the police and courts. Constitutionalists argue[63] that this is because contracts with the monarch such as the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Rights, the Act of Settlement and the Acts of Union place obligations on the state and[64] confirm its citizens as sovereign beings. These obligations are re-affirmed at every monarch's coronation. These obligations, whilst at the same time placing limits on the power of the judiciary and the police, also confirm those rights which are intrinsically part of British and especially English culture.[65] Examples are Common Law, the particular status of ancient practices, jury trials, legal precedent, protection against non-judicial seizure and the right to protest.

- Provides a focal point for unity and tradition: Monarchists argue that a constitutional monarch with limited powers and non-partisan nature can provide a focus for national unity, national awards and honours, national institutions, and allegiance, as opposed to a president affiliated to a political party.[66]

British political scientist Vernon Bogdanor justifies monarchy on the grounds that it provides for a nonpartisan head of state, separate from the head of government, and thus ensures that the highest representative of the country, at home and internationally, does not represent a particular political party, but all people.[67]

According to Bogdanor, monarchies can play a helpful unifying role in a multinational state, noting that "In Belgium, it is sometimes said that the king is the only Belgian, everyone else being either Fleming or Walloon" and that the British sovereign can belong to all of the UK's constituent countries (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), without belonging to any particular one of them.[67]

- Helps avoid extreme politics: British-American libertarian writer Matthew Feeney argues that European constitutional monarchies "have managed for the most part to avoid extreme politics"—specifically fascism, communism, and military dictatorship—"in part because monarchies provide a check on the wills of populist politicians" by representing entrenched customs and traditions.[68] Feeny notes that

European monarchies – such as the Danish, Belgian, Swedish, Dutch, Norwegian, and British – have ruled over countries that are among the most stable, prosperous, and free in the world.[68]

- Does not cost more than a republic would: Some argue that if there were a republic, the costs incurred in regards to the duties of the head of state would remain more or less the same. This includes the upkeep and conservation of the royal palaces and buildings which would still have to be paid for as they belong to the nation as a whole rather than the monarch personally. On top of that, the head of state would require a salary and security, state visits, banquets and ceremonial duties would still go ahead. In 2009, the monarchy claimed to be costing each person an estimated 69 pence a year (not including "a hefty security bill").[69][70] However, the figure of 69p per person has been criticised for having been calculated by dividing the overall figure by approximately 60 million people, rather than by the number of British taxpayers.[71]

- Arose from disillusionment with a failed republic: Some people[who?] point out that a republican government under the Commonwealth of England and then the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland has already been tried when Oliver Cromwell installed it on 30 January 1649.[72] Yet by February 1657 some people[who?] argued that Cromwell should assume the Crown as it would stabilise the constitution, limit his powers and restore precedent.[73] He declined and within three years of his death the Commonwealth had lost support and the monarchy was restored. Later, during The Glorious Revolution of 1688 caused partially by disillusionment with the absolutist rule of James II and VII, Parliament and others, such as John Locke[74] argued that James had broken "the original contract" with the state. Far from pressing for a republic, which had been experienced within living memory, they instead argued that the best form of government was a constitutional monarchy with explicitly circumscribed powers.

See also[]

- Abolition of monarchy

- Criticism of monarchy

- List of advocates of republicanism in the United Kingdom

- Movement Against the Monarchy

- Scottish republicanism

- Welsh republicanism

- Irish republicanism

- Republicanism in Northern Ireland

- Republics in the Commonwealth of Nations

- Secular state

References[]

- ^ Salmond, Alex (January 2012). "Scotland's place in the world". Scottish National Party. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013.

- ^ Wiemann, Dirk; Mahlberg, Gaby (ed.) (2016). Perspectives on English Revolutionary Republicanism. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-317-08176-0. Retrieved 22 June 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Loomie, Albert (2004). "Oliver Cromwell's Policy toward the English Catholics: The Appraisal by Diplomats, 1654–1658". The Catholic Historical Review. 90: 29–44 – via https://www.jstor.org/stable/25026519?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- ^ White, Daniel E. (2006). Early Romanticism and Religious Dissent. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-85895-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foner, Eric (2005). Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–82. ISBN 978-0-19-517486-1. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hitchens, Christopher (23 October 2007). "Hitchens: How Paine's 'Rights' Changed the World". NPR Books. NPR. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Honohan, Iseult; Jennings, Jeremy (2006). Republicanism in Theory and Practice. Psychology Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-415-35736-4. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Butler, Marilyn, ed. (1984). Burke, Paine, Godwin, and the Revolution Controversy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-521-28656-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bloom, Clive (2012). Riot City. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 156–158. ISBN 978-1-137-02937-9. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Law Lords. "Regina v Her Majesty's Attorney General (Appellant) ex parte Rusbridger and another (Respondents)". House of Lords. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Olechnowicz, Andrzej (2007). The Monarchy and the British Nation, 1780 to the Present. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-84461-1.

- ^ Costa, Thomas M. (1996). "Dilke, Charles Wentworth". In Olson, James S.; Shadle, Robert (eds.). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27917-9.

- ^ Reid, Fred (1978). Keir Hardie: The Making of a Socialist. London, UK: Croom Helm. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-85664-624-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Martin, Kingsley (1962). The Crown and the Establishment. London, UK: Hutchinson. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Pugh, Martin (2011). Speak for Britain!: A New History of the Labour Party. London, UK: Vintage Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-09-952078-8.

- ^ Paxman, Jeremy (2008). On Royalty : A Very Polite Inquiry Into Some Strangely Related Families. New York City: PublicAffairs. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-1-58648-491-0.

- ^ Judd, Denis (2012). George VI. London, UK: IB Tauris. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-78076-071-1.

- ^ Brockway, Fenner (1949). Bermondsey Story: The Life of Alfred Salter. London, UK: Allen & Unwin. p. 201.

- ^ Willie Hamilton, My Queen and I. London, Quartet Books, 1975.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Early day motion 1075: Commonwealth of Britain Bill". UK Parliament. 1 July 1996.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Britain Bill". Hansard. House of Commons. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Benn, Tony; Hood, Andrew (17 June 1993). Hood, Andrew (ed.). Common Sense: New Constitution for Britain. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-177308-3.

- ^ Borrill, Rachel (8 January 1997). "66% 'yes' vote to monarchy in TV 'phone poll contradicts previous result". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Queen's Speech: Dennis Skinner's top heckles". New Statesman. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Adams, Tim (30 July 2017). "Dennis Skinner: 'I've never done any cross-party stuff. I can't even contemplate it'". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Monarchy/Royal Family Trends – Monarchy v Republic 1993–2013". Ipsos MORI. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "PM and Palace 'discussed reform'". BBC News. 29 March 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ "Positively princely". YouGov. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 27 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Poll shows support for Royal Family". The Guardian. London, UK. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Wallis, Holly (27 May 2012). "Diamond Jubilee v Republican Britain". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Prince Charles hits out at climate change sceptics". BBC News. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Proctor, Kate (13 June 2015). "Labour MPs switch from Andy Burnham to left-winger Jeremy Corbyn in leadership race". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Who is Jeremy Corbyn? Labour leadership contender guide". BBC News. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "Republic — MPs break convention to swear allegiance to the people". Republic. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Young Britons are turning their backs on the monarchy". YouGov. 21 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Smith, Graham (16 April 2010). "Could we have the first republican party MPs after this election?". Republic. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Conservative politician urges Sinn Fein MPs to take seats in House of Commons". Belfast Telegraph. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Scottish Independence" (PDF). Scottish Green Party. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "About". Labour for a Republic. 18 June 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Building support within the Labour Party". Labour for a Republic. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Wheeler, Brian (24 September 2014). "The secret life of Labour's republicans". BBC News. Retrieved 20 February 2019. Ken Ritchie is misspelt as Ken Richey but is the same person.

- ^ Booth, Robert (20 August 2009). "Prince Charles's architecture foundation could face investigation". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Katawala, Sunder (7 February 2012). "The monarchy is more secure than ever". New Statesman. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Readers give their verdict: first fix the electoral system". The Guardian. London, UK. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What we want". Republic. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Hames, Tim; Leonard, Mark (1998). Modernising the Monarchy. London, UK: Demos. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-898309-74-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The case for a republic". Republic. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Bertram, Christopher (2004). Rousseau and The Social Contract. Routledge Philosophy GuideBook. London, UK: Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-41520-198-8.

- ^ Moreton, Cole (17 March 2012). "Falkland Islands: Britain 'would lose' if Argentina decides to invade now". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK.

- ^ "Prince Charles awarded highest rank in all three armed forces". The Daily Telegraph. 28 March 2017.

- ^ "The royal family can't keep ignoring its colonialist past and racist present". Benjamin T. Jones. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Hari, Johann (2002). "Chapter One". God Save the Queen?. Cambridge, UK: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-401-6. Archived from the original on 17 March 2006 – via JohannHari.com.

- ^ "Charles furore grows with Tibet missive". World Tibet Network News. 26 September 2002. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- ^ "Palace defends prince's letters". BBC News. 25 September 2002.

- ^ Assinder, Nick (9 February 2000). "Royals dragged into Haider row". BBC News.

- ^ "Royal finances". Republic. 30 December 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ Allen, Nick (14 June 2008). "Britain should get rid of the monarchy, says UN". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Royal Finances". Republic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Blain, Neil; O'Donnell, Hugh (2003). Media, Monarchy and Power. Intellect Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-84150-043-0.

- ^ Long, Phil; Palmer, Nicola J. (2007). Royal Tourism: Excursions Around Monarchy. Channel View Publications. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-84541-080-3.

- ^ Booth, Robert (31 August 2012). "Secret royal veto powers over new laws to be exposed". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ Syal, Rajeev; Mulholland, Helene (18 December 2012). "Queen attends cabinet meeting". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ "Constitutional Monarchy". British Monarchist League. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Constitutional Matters". The Baronage Press Ltd. 1995. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Maer, Lucinda; Gay, Oonagh (5 October 2009). "The Bill of Rights 1689" (PDF). House of Commons Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Bogdanor, Vernon (1997). "Chapter 11". The Monarchy and the Constitution. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19829-334-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bogdanor, Vernon (6 December 2000). "The Guardian has got it wrong". The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feeney, Matthew (25 July 2013). "The Benefits of Monarchy". Reason magazine.

- ^ "The cost of the British Monarchy? A mere 69 pence per person". Toronto Star. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012.

- ^ The Press Secretary to the Queen (29 June 2009). "Head of State Expenditure". The British Monarchy. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Cost of Royal Family rises £1.5m". BBC News. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Plant, David (17 September 2008). "The Rump Parliament". British Civil Wars and Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Plant, David (18 May 2007). "Biography of Oliver Cromwell". British Civil Wars and Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Powell, Jim (August 1996). "John Locke: Natural Rights to Life, Liberty, and Property". The Freeman Online. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

Further reading[]

- Bloom, Clive (2010). Restless Revolutionaries : A History of Britain's Fight for a Republic. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75245-856-4.

- Hitchens, Christopher (1990). The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain's Favourite Fetish. London, UK: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-1-4481-5535-4.

- Mahlberg, Gaby; Wiemann, Dirk (2013). European Contexts for English Republicanism. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-5556-1.

- Nairn, Tom (2011). The Enchanted Glass: Britain and its Monarchy. London, UK: Verso Books. p. 978-1-84467-775-7.

- Scott, Jonathan (2004). Commonwealth Principles: Republican Writing of the English Revolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84375-8.

- Taylor, Anthony (1999). "Down with The Crown" : British anti-monarchism and debates about royalty since 1790. London, UK: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-049-4.

- Taylor, Anthony; Nash, David (2000). Republicanism in Victorian Society. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-1856-X.

- Wiemann, Dirk; Mahlberg, Gaby, eds. (2016). Perspectives on English Revolutionary Republicanism. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-08176-0.

External links[]

- Republic website and Republic Twitter page

- Labour for a Republic website

- Throneout website and Throneout Facebook page

- Centre for Citizenship

- International Monarchist League

- BritRepub Twitter page

- Res Publica: Britain international anti-monarchy Web directory

- The Democratic Republican Party

- The Electoral Commission

- Republicanism in the United Kingdom

- Republicanism by country