Spitsbergen

Map of the Svalbard archipelago, with Spitsbergen emphasized in solid red. Inset shows the islands' place in Northern Europe. | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Arctic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 78°45′N 16°00′E / 78.750°N 16.000°ECoordinates: 78°45′N 16°00′E / 78.750°N 16.000°E |

| Archipelago | Svalbard |

| Area | 37,673 km2 (14,546 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 36th |

| Highest elevation | 1,717 m (5633 ft)[1] |

| Highest point | Newtontoppen |

| Administration | |

Norway | |

| Largest settlement | Longyearbyen (pop. 2,417) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,884 (2020) |

Spitsbergen (Urban East Norwegian: [ˈspɪ̀tsˌbærɡn̩]; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: Vest Spitsbergen or Vestspitsbergen [ˈvɛ̂stˌspɪtsbærɡn̩], also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen)[2][3][4][5] is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norway.

Constituting the westernmost bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea, and the Greenland Sea. Spitsbergen covers an area of 37,673 km2 (14,546 sq mi), making it the largest island in Norway and the 36th-largest in the world. The administrative centre is Longyearbyen. Other settlements, in addition to research outposts, are the Russian mining community of Barentsburg, the research community of Ny-Ålesund, and the mining outpost of Sveagruva. Spitsbergen was covered in 21,977 km2 (8,485 sq mi) of ice in 1999, which was approximately 58.5% of the island's total area.

The island was first used as a whaling base in the 17th and 18th centuries, after which it was abandoned. Coal mining started at the end of the 19th century, and several permanent communities were established. The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 recognized Norwegian sovereignty and established Svalbard as a free economic zone and a demilitarized zone.

The Norwegian Store Norske and the Russian Arktikugol are the only mining companies at Spitsbergen. Research and tourism have become the important supplementary industries, featuring among others the University Centre in Svalbard and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. No roads connect the settlements; instead snowmobiles, aircraft, and boats serve as local transport. Svalbard Airport, Longyear provides the main point of entry and exit.

The island has an Arctic climate, although with significantly higher temperatures than other places at the same latitude. The flora benefits from the long period of midnight sun, which compensates for the polar night. Svalbard is a breeding ground for many seabirds, and also supports polar bears, arctic foxes, reindeer and marine mammals. Six national parks protect the largely untouched, yet fragile environment. The island has many glaciers, mountains, and fjords.

Etymology[]

The Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz gave Spitsbergen its name when he discovered it in 1596. The name Spitsbergen, meaning "pointed mountains" (from the Dutch spits - pointed, bergen - mountains),[6] at first applied both to the main island and to the associated archipelago as a whole. In the 17th and 18th centuries, English whalers referred to the islands as "Greenland",[7] a practice still followed in 1780 and criticized by Sigismund Bacstrom at that time.[8] The "Spitzbergen" spelling was used in English during the 19th century, for instance by Beechey,[9] Laing,[10] and the Royal Society.[11]

In 1906 the Arctic explorer Sir Martin Conway regarded the Spitzbergen spelling as incorrect; he preferred Spitsbergen, as he noted that the name was Dutch, not German.[12] This had little effect on British practice.[13][14] In 1920 the international treaty determining the status of the islands was entitled the "Spitsbergen Treaty". The islands were generally referred to in the United States as "Spitsbergen" from that time,[15] although the spelling "Spitzbergen" also commonly occurred through the 20th century.[16][17][18]

The Norwegian administrating authorities named the archipelago Svalbard in 1925, the main island becoming Spitsbergen. By the end of the 20th century, this usage had become common.

History[]

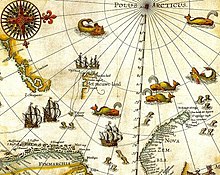

The first recorded sighting of the island by a European was by Willem Barentsz, who came across it while searching for the Northern Sea Route in June 1596.[19] The first good map, with the east coast roughly indicated, appeared in 1623, printed by Willem Janszoon Blaeu. Around 1660 and 1728, better maps were produced.[20][21]

The archipelago may have been known to Russian Pomor hunters as early as the 14th or 15th century, although solid evidence preceding the 17th century is lacking. Following the English whalers and others in referring to the archipelago as Greenland, they named it Grumant (Грумант). The name Svalbard is first mentioned in Icelandic sagas of the 10th and 11th centuries, but this may have been Jan Mayen.

Early claims[]

Early whaling expeditions to Svalbard in general and Spitsbergen in particular tended, because of currents and fauna, to cluster on the western coast of Spitsbergen and the islands off shore. Shortly after whaling began (1611), the Danish—Norwegian crown in 1616 claimed ownership of Jan Mayen and the Spitsbergen islands, as all of Svalbard was then known, but in 1613, the English Muscovy Company had done the same.

The primary and most profitable whaling grounds of this joint-stock company came to be centered on Spitsbergen in the early 17th century, and the company's 1613 Royal Charter from the English Crown granted a monopoly on whaling in Spitsbergen, based on the (erroneous) claim that Hugh Willoughby had discovered the land in 1553.[22][23] Not only had they wrongly assumed a 1553 English voyage had reached the area, but on 27 June 1607, during his first voyage in search of a "northeast passage" on behalf of the company, Henry Hudson sighted "Newland" (i.e. Spitsbergen), near the mouth of the great bay Hudson later named the Great Indraught (Isfjorden). In this way, the English hoped to head off expansion in the region by the Dutch, at the time their major rival.[24][25] Initially, the English tried to drive away competitors, but after disputes with the Dutch (1613–24), they, for the most part, only claimed the bays south of Kongsfjorden.[26]

Danish expansion[]

From 1617 onwards, a Danish-chartered company began sending whaling fleets to Spitsbergen.[27] This successful expansion by Denmark into the North Atlantic has recently been cited by historians as the first step of the Danish-Norwegian state into overseas colonialism. It eventually built a small overseas empire of East Indian trade posts, North Atlantic possessions (such as Greenland and Iceland), and a small Atlantic trade route between possessions on the Guinea Coast (in modern Ghana) and what are now the United States Virgin Islands.[28][29]

The entire Svalbard archipelago, nominally ruled first by Denmark–Norway, and later the Norwegians (as Union between Sweden and Norway from 1814 to 1905, independent Norway from 1905), remained a source of riches for fishery and whaling vessels from many nations. The islands also became the launching point for a number of Arctic explorers, including William Edward Parry, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, Otto Martin Torell, Alfred Gabriel Nathorst, Roald Amundsen, and Ernest Shackleton.

Spitsbergen Treaty[]

Between 1913 and 1920, Spitsbergen was a neutral condominium. The Spitsbergen Treaty of 9 February 1920, recognises the full and absolute sovereignty of Norway over all the arctic archipelago of Svalbard.[30] The exercise of sovereignty is, however, subject to certain stipulations, and not all Norwegian law applies. Originally limited to nine signatory nations, over 40 are now signatories of the treaty. Citizens of any of the signatory countries may settle in the archipelago. Once named Spitsbergen after its largest island, the Svalbard archipelago was made a part of Norway – not a dependency – by the Svalbard Act of 1925. Since this date, it has been a region of Norway, with a Norwegian-appointed governor resident at the administrative centre of Longyearbyen. Limitations on the imposition of certain Norwegian laws are outlined in the Spitsbergen Treaty.

The largest settlement on Spitsbergen is the Norwegian town of Longyearbyen, while the second-largest settlement is the Russian coal-mining settlement of Barentsburg. (This was sold by the Netherlands in 1932 to the Soviet company Arktikugol.) Other settlements on the island include the former Russian mining communities of Grumantbyen and Pyramiden (abandoned in 1961 and 1998, respectively), a Polish research station at Hornsund, and the remote northern settlement of Ny-Ålesund.[31]

World War II[]

Allied soldiers were stationed on the island in 1941 to prevent Nazi Germany from occupying the islands. Norway came under German occupation in 1940. Germany took control of the oil fields and the weather station during this time, although most of the inhabitants on the island were Russian and Germany and the Soviet Union had a non-aggression pact until 22 June 1941. Once the non-aggression pact was ended, the United Kingdom and Canada sent military forces to the island to destroy German installations, both the Soviet coal mines and the German weather station.[32]

In 1943, the German battleship Tirpitz and an escort flotilla shelled and destroyed the Allied weather station in Operation Zitronella. On 6 September, a squadron consisting of Tirpitz, the battleship Scharnhorst, and nine destroyers weighed anchor in Altenfjord and Kåfjord and headed for Spitsbergen, to attack the Allied base. At dawn on 8 September 1943, Tirpitz and Scharnhorst opened fire against the two 3-inch guns which comprised the defences of Barentsburg, and the destroyers ran inshore with landing parties, destroying a supply dump and wrecking a landing station. By noon, the hostilities had ended, with the landing parties returning to the ships, along with some prisoners. The German ships returned safely to Altenfjord and Kåfjord on 9 September 1943. This was the last operation for the Tirpitz.[33]

Postwar[]

On 29 August 1996, Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801 crashed on the island, killing all 141 people on board.[34]

Government[]

The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 established full Norwegian sovereignty over Svalbard. All 40 signatory countries of the treaty have the right to conduct commercial activities on the archipelago without discrimination, although all activity is subject to Norwegian legislation. The treaty limits Norway's right to collect taxes to that of financing services on Svalbard. Spitsbergen is a demilitarized zone, as the treaty prohibits the establishment of military installations. The treaty requires Norway to protect the natural environment.[35][36] The island is administered by the Governor of Svalbard, who holds the responsibility as both county governor and chief of police, as well as authority granted from the executive branch.[37] Although Norway is part of the European Economic Area (EEA) and the Schengen Agreement, Svalbard is not part of the Schengen Area nor EEA.[38]

Residents of Spitsbergen do not need visas for Schengen but are prohibited from reaching Svalbard from mainland Norway without them. People without a means of income can be rejected as residents by the governor.[39] Citizens of any treaty signatory country may visit the island without a visa.[40] Russia retains a consulate in Barentsburg.[41]

Population[]

In 2009, Spitsbergen had a population of 2,753, of whom 423 were Russian or Ukrainian, 10 were Polish and 322 were non-Norwegians living in Norwegian settlements.[42] The largest non-Norwegian groups in Longyearbyen in 2005 were from Thailand, Sweden, Denmark, Russia and Germany.[43] Spitsbergen is among the safest places on Earth, with virtually no crime.[44]

Longyearbyen is the largest settlement on the island, the seat of the governor, and the only incorporated town. It features a hospital, primary and secondary school, university, sports centre with a swimming pool, library, cultural centre, cinema,[45] bus transport, hotels, a bank,[46] and several museums.[47] The newspaper Svalbardposten is published weekly.[48] Only a small fraction of the mining activity remains at Longyearbyen; instead, workers commute to Sveagruva (or Svea) where Store Norske operates a mine. Sveagruva is a dorm town, with workers commuting from Longyearbyen on a weekly basis.[45]

Since 2002, Longyearbyen Community Council has had many of the same responsibilities of a municipality, including utilities, education, cultural facilities, fire department, roads and ports.[49] No care or nursing services are available, nor is welfare payment available. Norwegian residents retain pension and medical rights through their mainland municipalities.[50] The hospital is part of University Hospital of North Norway, while the airport is operated by state-owned Avinor. Ny-Ålesund and Barentsburg are company towns with all infrastructure owned by Kings Bay and Arktikugol, respectively.[49] Other public offices with presence on Svalbard are the Norwegian Directorate of Mining, the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Norwegian Tax Administration and the Church of Norway.[51] Svalbard is subordinate Nord-Troms District Court and Hålogaland Court of Appeal, both located in Tromsø.[52]

Ny-Ålesund is a permanent settlement based entirely on research. Formerly a mining town, it is still a company town operated by the Norwegian state-owned Kings Bay. While there is some tourism at the village, Norwegian authorities limit the access to the outpost to minimise impact on the scientific work.[45] Ny-Ålesund has a winter population of 35 and a summer population of 180.[53] Poland operates the Polish Polar Station at Hornsund, with ten permanent residents.[45]

Barentsburg is the only remaining Russian settlement, after Pyramiden was abandoned in 1998. A company town, all facilities are owned by Arktikugol, which operates a coal mine. In addition to the mining facilities, Arktikugol has opened a hotel and souvenir shop, catering to tourists taking day trips or hikes from Longyearbyen.[45] The village has facilities such as a school, library, sports center, community center, swimming pool, farm and greenhouse. Pyramiden has similar facilities; both are built in typical Soviet style and are the site of the world's two most northerly Lenin statues and other socialist realism artwork.[54]

Economy[]

The three main industries on Spitsbergen are coal mining, tourism and research. In 2007, there were 484 people working in the mining sector, 211 people working in the tourism sector and 111 people working in the education sector. The same year, mining produced a revenue of NOK 2,008 million, tourism NOK 317 million and research NOK 142 million.[49] In 2006, the average income for economically active people was NOK 494,700 – 23% higher than on the mainland.[55] Almost all housing is owned by the various employers and institutions and rented to their employees; there are only a few privately owned houses, most of which are recreational cabins. Because of this, it is almost impossible to live on Spitsbergen without working for an established institution.[39]

Since the resettlement of Spitsbergen in the early 20th century, coal mining has been the dominant commercial activity. Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, a subsidiary of the Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry, operates Svea Nord in Sveagruva and Mine 7 in Longyearbyen. The former produced 3.4 million tonnes in 2008, while the latter sends 35% of its output to Longyearbyen Power Station. Since 2007, there has not been any significant mining by the Russian state-owned Arktikugol in Barentsburg. There has previously been some test drilling for petroleum on land, but this did not give results good enough to justify permanent operation. The Norwegian authorities do not allow offshore petroleum drilling activities for environmental reasons, and the land formerly test-drilled on has been protected as nature reserves or national parks.[49]

Spitsbergen Island coins were issued in 1946, with Russian Cyrillic lettering, in the USSR denomination of 10 and 20 kopecks. Then in 1993, coins were again minted in Russian values of 10, 20, 50, and 100 roubles. Both series have the motto "Arctic coal".

Spitsbergen has historically been a base for both whaling and fishing. Norway claimed a 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around Svalbard in 1977,[56] Norway retains a restrictive fisheries policy in the zone,[56] and the claims are disputed by Russia.[57] Tourism is focused on the environment and is centered on Longyearbyen. Activities include hiking, kayaking, walks through glacier caves and snow-scooter and dog-sled safaris. Cruise ships generate a significant portion of the traffic, including stops by both offshore vessels and expeditionary cruises starting and ending in Svalbard. Traffic is strongly concentrated between March and August; overnight stays have quintupled from 1991 to 2008, when there were 93,000 guest-nights.[49]

Research on Svalbard centers on Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, the most accessible areas in the high Arctic. Norway grants permission for any nation to conduct research on Svalbard, resulting in the Polish Polar Station, Indian Himadri Station, and the Chinese Arctic Yellow River Station, plus Russian facilities in Barentsburg.[58] The University Centre in Svalbard in Longyearbyen offers undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate courses to 350 students in various arctic sciences, particularly biology, geology and geophysics. Courses are provided to supplement studies at the mainland universities; there are no tuition fees and courses are held in English, with Norwegian and international students equally represented.[59]

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a "doomsday" seedbank to store seeds from as many of the world's crop varieties and their botanical wild relatives as possible. A cooperation between the government of Norway and the Global Crop Diversity Trust, the vault is cut into rock near Longyearbyen, keeping it at a natural −6 °C (21 °F) and refrigerating the seeds to −18 °C (0 °F).[60][61]

The Svalbard Undersea Cable System is a 1,440 km (890 mi) fibre optic line from Svalbard to Harstad, needed for communicating with polar orbiting satellite through Svalbard Satellite Station and installations in Ny-Ålesund.[62][63]

The Arctic World Archive, a huge digital archiving concern run by Norwegian private company and the state-owned coal-mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, opened in March 2017.[64] In mid-2020, it acquired its biggest customer in the form of GitHub, a subsidiary of Microsoft.[65]

Transport[]

Within Longyearbyen, Barentsburg and Ny-Ålesund, there are road systems, but they do not connect with each other. Off-road motorized transport is prohibited on bare ground, but snowmobiles are used extensively during winter – both for commercial and recreational activities. Transport from Longyearbyen to Barentsburg (45 km or 28 mi) and Pyramiden (100 km or 62 mi) is possible by snowmobile during winter, or by ship all year round. All settlements have ports, and Longyearbyen has a bus system.[66]

Svalbard Airport, Longyear, located 3 kilometres (2 mi) from Longyearbyen, is the only airport offering air transport for the island. Scandinavian Airlines has daily scheduled services to Tromsø and Oslo; there are also irregular charter services to Russia.[67] Lufttransport provides regular corporate charter services from Longyearbyen to Ny-Ålesund Airport, Hamnerabben and Svea Airport for Kings Bay and Store Norske; these flights are in general not available to the public.[68] There are heliports in Barentsburg and Pyramiden, and helicopters are frequently used by the governor and to a lesser extent the mining company Arktikugol.[69]

Climate[]

The climate of Svalbard is dominated by its high latitude, with the average summer temperature at 4 °C (39 °F) to 6 °C (43 °F) and January averages at −12 °C (10 °F) to −16 °C (3 °F).[70] The North Atlantic Current moderates Spitsbergens's temperatures, particularly during winter, giving it up to 20 °C (36 °F) higher winter temperature than similar latitudes in Russia and Canada. This keeps the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The interior fjord areas and valleys, sheltered by the mountains, have less temperature differences than the coast, giving about 2 °C (4 °F) lower summer temperatures and 3 °C (5 °F) higher winter temperatures. On the south of Spitsbergen, the temperature is slightly higher than further north and west. During winter, the temperature difference between south and north is typically 5 °C (9 °F), while about 3 °C (5 °F) in summer.[71]

Spitsbergen is the meeting place for cold polar air from the north and mild, wet sea air from the south, creating low pressure and changing weather and fast winds, particularly in winter; in January, a strong breeze is registered 17% of the time at Isfjord Radio, but only 1% of the time in July. In summer, particularly away from land, fog is common, with visibility under 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) registered 20% of the time in July.[72] Precipitation is frequent but falls in small quantities, typically less than 400 millimetres (16 in) annually in western Spitsbergen. More rain falls in the uninhabited east side, where there can be more than 1,000 millimetres (39 in) annually.[72]

Nature[]

Three terrestrial mammalian species inhabit the island: the Arctic fox, the Svalbard reindeer, and accidentally introduced southern vole, which are only found in Grumant.[73] Attempts to introduce the Arctic hare and the muskox have both failed.[74] There are fifteen to twenty types of marine mammals, including whales, dolphins, seals, walruses, and polar bears.[73] Arctic charr inhabit Linne´vatn and other freshwater lakes on the island.[75]

Polar bears are the iconic symbol of Spitsbergen and one of the main tourist attractions.[76] While they are protected, persons going outside settlements are required to carry a rifle to kill polar bears in self-defence, as a last resort should they attack.[77] Spitsbergen shares a common polar bear population with the rest of Svalbard and Franz Joseph Land. The Svalbard reindeer (R. tarandus platyrhynchus) is a distinct sub-species. While it was previously almost extinct, hunting is permitted for both it and the Arctic fox.[73]

About thirty types of bird are found on Spitsbergen, most of which are migratory. The Barents Sea is among the areas in the world with most seabirds, with about 20 million counted during late summer. The most common are little auk, northern fulmar, thick-billed murre and black-legged kittiwake. Sixteen species are on the IUCN Red List. Particularly Storfjorden and Nordvest-Spitsbergen are important breeding ground for seabirds. The Arctic tern has the furthest migration, all the way to Antarctica.[73] Only two songbirds migrate to Spitsbergen to breed: the snow bunting and the wheatear. Rock ptarmigan is the only bird to overwinter.[78]

Two partial skeletons of Pliosaurus funkei from the Jurassic period were discovered in 2008. It is the largest Mesozoic marine reptile ever found – a pliosaur estimated to be almost 15 m (49 ft) long.[79] Svalbard has permafrost and tundra, with both low, middle and high Arctic vegetation. 165 species of plants have been found on the archipelago.[73] Only those areas which defrost in the summer have vegetation.[80] Vegetation is most abundant in Nordenskiöld Land, around Isfjorden and where effected by guano.[81] While there is little precipitation, giving the island a steppe climate, plants still have good access to water because the cold climate reduces evaporation.[72][73] The growing season is very short, and may last only a few weeks.[82]

There are six national parks on Spitsbergen: Indre Wijdefjorden, Nordenskiöld Land, Nordre Isfjorden Land, Nordvest-Spitsbergen, Sassen-Bünsow Land and Sør-Spitsbergen.[83] The island also features Festningen Geotope Protected Area; some of the northeastern coast is part of Nordaust-Svalbard Nature Reserve.[84] All human traces dating from before 1946 are automatically protected.[77] Svalbard is on Norway's tentative list for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[85]

See also[]

- Cape Amsterdam

- Einar Lundborg

References[]

- ^ Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 355. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ^ "Of this Spitsbergen archipelago, the main island (the biggest) had the Norwegian name 'Vest Spitsbergen' ('West Spitsbergen' in English).” Umbreit, Spitsbergen (2009), p. ix.

- ^ ”Spitsbergen… an Arctic archipelago… comprising the five large islands of West Spitsbergen…”. Hugh Chisholm (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), p. 708

- ^ ”… the Archipelago of Spitsbergen, comprising, with Bear Island… all the islands situated between 10deg. and 35deg. longitude East of Greenwich and between 74deg. and 81 deg. latitude North, especially West Spitsbergen…” Treaty concerning the Archipelago of Spitsbergen (1920), p. 1.

- ^ Berulfsen, Bjarne (1969). Norsk Uttaleordbok (in Norwegian). Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co (W Nygaard). pp. 301, 356.

- ^ In Search of Het Behouden Huys: A Survey of the Remains of the House of Willem Barentsz on Novaya Zemlya, LOUWRENS HACQUEBORD, p. 250

- ^ Fotherby, (1613) P45 [1] by Haven, S (1860)

- ^ "Account of a voyage 1780", Philosophical Magazine, 1799

- ^ Description Aston Barker, Beechey,

- ^ A Voyage Laing 1822

- ^ Proceedings vol 12 Royal Society 1863

- ^ "Spitsbergen is the only correct spelling; Spitzbergen is a relatively modern blunder. The name is Dutch, not German. The second S asserts and commemorates the nationality of the discoverer." – Sir Martin Conway, No Man's Land, 1906, p. vii.

- ^ Lockyer, N "The Conway expedition to Spitzbergen", Nature (1896)

- ^ British documents on foreign affairs British Foreign Office (1908)

- ^ TIME magazine NORWAY: Formal Annexation

- ^ Hansard (1977)

- ^ Jackson, Gordon (1978). The British Whaling Trade. Archon. ISBN 0-208-01757-7.

- ^ Chart of historical usage trends

- ^ "No Man's Land". CUP Archive. 1982.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Hudson, Henry; Georg Michael Asher (1860). Henry Hudson the Navigator: The Original Documents in which His Career is Recorded, Collected, Partly Translated, and Annotated. London: Hakluyt Society. pp. clix–clx.

- ^ Schokkenbroek, Joost C.A. (2008). Trying-out: An anatomy of Dutch Whaling and Sealing in the Nineteenth Century, 1815-1885, p. 27.

- ^ pp.1-22. Georg Michael Asher,(1860). Henry Hudson the Navigator. Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 27. ISBN 1-4021-9558-3.

- ^ William Martin Conway, (1906). No Man's Land: A History of Spitsbergen from Its Discovery in 1596 to the Beginning of the Scientific Exploration of the Country. Cambridge, At the University Press.

- ^ Schokkenbroek, p. 28.

- ^ pp. 18-20 in Már Jónsson. "Denmark-Norway as a Potential World Power in the Early Seventeenth Century", Itinerario, Volume 33, Issue 02, July 2009, pp 17-27.

- ^ Már Jónsson (2009) passim.,

- ^ Pernille Ipsen and Gunlög Fur. "Introduction to Scandinavian Colonialism", Itinerario, Volume 33, Issue 02, July 2009, pp 7-16.

- ^ Knowles, Daniel (2018) Tirpitz:The Life And Death of Germany's Last Great Battleship (Stroud:Fonthill Media)

- ^ "Northern Townships: Spitsbergen", Hidden Europe magazine, 10 (September 2006), pp.2-5

- ^ "Spitsbergen Operation", Lone Sentry website

- ^ Asmussen, John. "Tirpitz - The History - Operation "Sizilien"". www.bismarck-class.dk.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Tupolev Tu-154M RA-85621 Svalbard-Longyearbyen Airport (LYR)". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ "Svalbard Treaty". Wikisource. 9 February 1920. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Svalbard Treaty". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "5 The administration of Svalbard". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Lov om gjennomføring i norsk rett av hoveddelen i avtale om Det europeiske økonomiske samarbeidsområde (EØS) m.v. (EØS-loven)" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2000. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Entry and residence". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 106

- ^ "Diplomatic and consular missions of Russia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Population in the settlements. Svalbard". Statistics Norway. 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Non-Norwegian population in Longyearbyen, by nationality. Per 1 January. 2004 and 2005. Number of persons". Statistics Norway. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 117

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "10 Longyearbyen og øvrige lokalsamfunn". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Shops/services". Svalbard Reiseliv. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Attractions". Svalbard Reiseliv. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 179

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "9 Næringsvirksomhet". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "From the cradle, but not to the grave" (PDF). Statistics Norway. Retrieved 24 March 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "6 Administrasjon". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Nord-Troms tingrett". Norwegian National Courts Administration. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Ny-Ålesund". Kings Bay. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 194–203

- ^ "Focus on Svalbard". Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "7 Industrial, mining and commercial activities". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Svalbard". World Fact Book. Central Intelligence Agency. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "8 Research and higher education". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999–2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Arctic science for global challenges". University Centre in Svalbard. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Hopkin, M. (15 February 2007). "Norway Reveals Design of Doomsday' Seed Vault". Nature. 445 (7129): 693. doi:10.1038/445693a. PMID 17301757.

- ^ "Life in the cold store". BBC News. 26 February 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Gjesteland, Eirik (2004). "Technical solution and implementation of the Svalbard fibre cable" (PDF). Telektronic (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Skår, Rolf (2004). "Why and how Svalbard got the fibre" (PDF). Telektronic (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Vincent, James (4 April 2017). "Keep your data safe from the apocalypse in an Arctic mineshaft". The Verge. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Linder, Courtney (15 November 2019). "Github Code - Storing Code for the Apocalypse". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Umbriet (1997): 63–67

- ^ "Direkteruter" (in Norwegian). Avinor. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "Charterflygning" (in Norwegian). Lufttransport. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "11 Sjø og luft – transport, sikkerhet, redning og beredskap". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008–2009): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Temperaturnormaler for Spitsbergen i perioden 1961 - 1990" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 98–99

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Torkilsen (1984): 101

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Protected Areas in Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 33

- ^ O'Malley, Kathleen G.; Vaux, Felix; Black, Andrew N. (2019). "Characterizing neutral and adaptive genomic differentiation in a changing climate: The most northerly freshwater fish as a model". Ecology and Evolution. 9 (4): 2004–2017. doi:10.1002/ece3.4891. PMC 6392408. PMID 30847088.

- ^ Torkildsen (1984): 174

- ^ Jump up to: a b Umbriet (2005): 132

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 162

- ^ "Enormous Jurassic Sea Predator, Pliosaur, Discovered in Norway". Science Daily. 29 February 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ Torkilsen (1984): 144

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 29–30

- ^ Umbreit (2005): 32

- ^ "Norges nasjonalparker" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Verneområder i Svalbard sortert på kommuner" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Svalbard". UNESCO. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

Bibliography[]

- Arlov, Thor B. (1996). Svalbards historie (in Norwegian). Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-22171-8.

- Arlov, Thor B. and Arne O. Holm (2001). Fra company town til folkestyre (in Norwegian). Longyearbyen: Svalbard Samfunnsdrift. ISBN 82-996168-0-8.

- Fløgstad, Kjartan (2007). Pyramiden: portrett av ein forlaten utopi (in Norwegian). Oslo: Spartacus. ISBN 978-82-430-0398-9.

- Tjomsland, Audun & Wilsberg, Kjell (1995). Braathens SAFE 50 år: Mot alle odds. Oslo. ISBN 82-990400-1-9.

- Torkildsen, Torbjørn; et al. (1984). Svalbard: vårt nordligste Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. ISBN 82-7010-167-2.

- Umbreit, Andreas (2005). Guide to Spitsbergen. Bucks: Bradt. ISBN 1-84162-092-0.

- Stange, Rolf (2011). Spitsbergen. Cold Beauty (Photo book) (in English, German, Dutch, and Norwegian). Rolf Stange. ISBN 978-3-937903-10-1. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012.

- Stange, Rolf (2012). Spitsbergen – Svalbard. A complete guide around the arctic archipelago. Rolf Stange. ISBN 978-3-937903-14-9. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spitsbergen. |

| Look up spitsbergen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Spitsbergen

- Islands of Svalbard

- 1590s in the Dutch Empire

- Maritime history of the Dutch Republic