Turtle-Flambeau Flowage

| Turtle-Flambeau Flowage | |

|---|---|

View of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage, looking Southwest from Fisherman's Landing | |

Turtle-Flambeau Flowage | |

| |

| Location | Iron County, Wisconsin, United States |

| Coordinates | 46°5′N 90°13′W / 46.083°N 90.217°WCoordinates: 46°5′N 90°13′W / 46.083°N 90.217°W |

| Type | Drainage |

| Primary inflows | Flambeau River, Turtle River |

| Primary outflows | Flambeau River |

| Catchment area | 639.727 km2 (247.000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 15.4 km (9.6 mi) |

| Max. width | 15.3 km (9.5 mi) |

| Surface area | 52.37 km2 (20.22 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Shore length1 | 368.54 km (229.00 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 519.4 m (1,704 ft) |

| Frozen | Ice melts in late April – early May |

| Islands | Big Island, plus many others |

| Settlements | Mercer, Butternut |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage is a 12,942 acres (52.37 km2) lake, in Iron County, Wisconsin.[1] It has a maximum depth of 15 meters and is the seventh largest lake in the state of Wisconsin by surface area. The flowage is home to unique wetland patterns and plant species as well as several species of sport and game fish, including Musky, Panfish, Largemouth Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Northern Pike, Walleye and Sturgeon. The lake's water clarity is low, but can vary in different locations in the lake.[2] Fishing, camping, boating, and hunting are popular activities on the flowage, and Ojibwe people traditionally harvest fish and game on the lake. Environmental concerns on the flowage include mercury contamination, algal blooms, and several types of invasive species.

Origins and history[]

The region which became the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage was originally a mix of forest, glades, kettle lakes, and rivers.[3] The area was originally part of the drainage system for the Flambeau River.

The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage was created in 1926 when the Chippewa and Flambeau Improvement Company built a dam on the Flambeau River downstream from its confluence with the Turtle River. The dam flooded 16 natural lakes and formed an impoundment of approximately 14,000 acres (57 km2).[3]

The flowage was constructed as a reservoir to augment river flows and sustain hydroelectric plants operated downstream by electric utilities and paper mills. The dam also provided flood protection and created a unique recreational resource.

Characteristics[]

Geography[]

The flowage's watershed covers nearly 640 square kilometers in Iron and Vilas Counties. 47% of the basin is forested, with another 33% covered by wetlands (including the Turtle-Flambeau Patterned Bog State Natural Area[4]) and 19% covered by open water. Human land use is relatively sparse; agriculture, urban, and suburban areas combined make up less than 1% of the land use in the watershed.[5]

Geology[]

The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage, like much of Iron County lies on top of a large granite formation from the Archean eon.[6] Soils are generally sandy, due to the presence of post-glaciation old growth coniferous forests.[7][8] .The majority of exposed rock formations in the area were either gouged, carved, or deposited by receding glaciers.[3] The flowage's basin is made up of approximately 45% sand, 30% gravel, 15% muck, and 10% rock.[9]

Hydrology[]

The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage is a drainage lake (a lake where the majority of discharge is to outgoing rivers).[10] It is fed by several rivers including the Flambeau River and Turtle River. The flowage discharges at the Turtle Dam into the Flambeau River.[11] Discharge from the dam is monitored by Xcel Energy, which operates several power stations on the Flambeau River downstream of the flowage. The dam's average discharge is 20 cubic meters per second; however, it varies greatly based on lake water levels and the energy company's hydroelectric needs.[12][13][14]

While the flowage's irregular nature makes it difficult to determine an average depth or volume, these determinations can be made for some of the old lake basins flooded by the dam.[3] Former lakes that were inundated during the flowage's formation include:[15]

| Former lakea | Former surface area (km2) (approx.)b | Basin volume (m3) (approx.)b |

|---|---|---|

| Blair Lake | 0.7455 | 2,272,000 |

| Sweeney Lake | 0.2455 | 1,122,000 |

| Mud Lake | 0.2273 | 692,700 |

| Merkle Lake | 1.559 | 3,198,000 |

| Turtle Lake | 1.455 | 3,547,000 |

| Rat Lake | 0.4091 | 845,100 |

| Lake Ten | 1.327 | 4,046,000 |

| Bastian Lake | 2.045 | 5,812,000 |

| Baraboo Lake | 1.595 | 5,757,000 |

| Townline Lake | 1.309 | 3,000,000 |

| Horseshoe Lake | 2.741 | 4,177,000 |

| Total | 13.658 | 34,468,800 |

| a: Landing Lake basin was also inundated but volume could not be calculated b: Area and volume calculated from bathymetry[16] using weight of excised depth intervals. | ||

The inundation of these lakes gives the flowage its irregular shape, with a shoreline development index of 12.91.[15] Roughly 35% of the reservoir's surface area is made up of former lake basins; the rest is made up of shallow riverine and transition zones.

Water quality[]

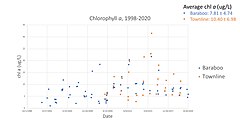

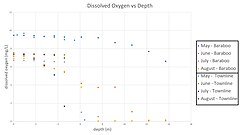

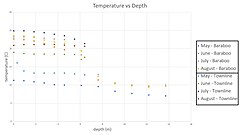

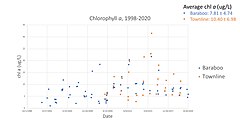

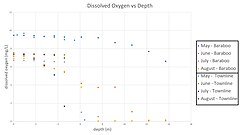

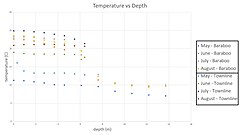

Water quality varies among the flowage's several basins (former lake beds), with Baraboo having the best overall water quality and Townline the worst.[17] While some basins (including Townline) resemble eutrophic lakes, others such as Baraboo are more accurately defined as mesotrophic. The reservoir is a productive and healthy lake with a water visibility going down approx. 1.5 m (5 feet) in the summer.[10] The flowage is a holomictic lake which develops a single thermocline of productive with productive water above and depleted water below.[10][18]

- Comparison of Secchi depth, chlorophyll a, total phosphorus, temperature, and dissolved oxygen in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage

Comparison of chlorophyll a levels in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage

Comparison of Secchi depth in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage

Comparison of total phosphorus levels in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage

Comparison of dissolved oxygen vs depth measurements in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau flowage

Comparison of temperature vs depth measurements in Baraboo and Townline basins of the Turtle-Flambeau flowage

Wildlife[]

Flora[]

While trees surrounding a body of water may not live in the lake: they may still affect lake levels. Through the process of transpiration, tree roots pull water found in moist shoreline: lowering the amount of water available in lake.[18] This rate of water collection is not even across all Wisconsin species. Trees endemic to wetlands such as the White Cedar are more efficient at transporting water in their sap than upland trees such as the Red Pine or Sugar Maple.[21]

The patterned bog in the southeast of the lake is a minerotrophic peatland with peat ridges separating water-filled hollows. This type of string bog is rare in Wisconsin.[4] Rare plant species present in the bog include sparse-flowered sedge (C. tenuiflora), dragon's mouth orchid (A. bulbosa), and white bog orchid (P. dilatata).[22]

Fauna[]

The lake is home to a wide variety of animals. Native fish include Musky, Panfish, Largemouth Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Northern Pike, Walleye and Sturgeon. Four water access points on the flowage also serve as fish stocking sites, with a fifth at the nearby Lake of the Falls impoundment.[23] Reptiles include snapping turtles and painted turtles.[24] The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage is also prime habitat for loons and features the largest concentration of eagle and osprey breeding pairs in Wisconsin.[4][25][26] Mammal species found living in and around the flowage include river otter, beaver, black bear, and white-tailed deer. Deer grazing in the area is heavy enough to threaten the regeneration of the area's conifers.[22]

Environmental concerns[]

Mercury[]

Significant levels of methylmercury have been found in walleye tissue in both the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage and other reservoirs in Oneida, Sawyer, and Vilas counties. Walleye are harvested as a traditional food source for the Lake Superior Chippewa, and the bioaccumulation of mercury in these fish increases the risk of harmful exposure to humans.[27] Wetlands are a major source of methylmercury in boreal forest environments,[28] and the variable discharge from flowage dams can increase methylmercury exposures in reservoirs.[27] The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage was declared impaired due to mercury contamination by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in 2002,[15] and a fish consumption warning has been in effect since 2009.[5]

Algae[]

Additional impairments include high levels of phosphorus and chlorophyll a, indicators of elevated algal growth.[15] The Mercer wastewater treatment plant, which discharges into the Little Turtle River, may provide some of the phosphorus input; nearby Mercer Lake suffers from algal blooms during periods of high discharge from the plant.[5] However, tannin-stained runoff from surrounding wetlands decreases light penetration in the flowage, reducing the potential impact of harmful algal blooms in comparison to other area lakes.[29]

Invasive species[]

Faucet snail[]

The faucet snail (Bithynia tentaculata) is an invasive aquatic snail from Europe. It outcompetes local species of snail throughout the Great Lakes region.[30] This snail has been observed in Spider Lake, a tributary of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage.[30]

Purple loosestrife[]

Purple loosestrife, native to Asia, Europe, northwest Africa, and southeastern Australia, is an invasive species in Wisconsin. It has been observed in 445 lakes and rivers in Wisconsin, including the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage.[31] The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage & Trude Lake Property Owners Association monitors purple loosestrife around the flowage. They conduct annual surveys and maintain a map displaying locations where the plant has been spotted.[32][33]

Spiny waterflea[]

The spiny waterflea (Bythotrephes longimanus) is a prodigious arthropod predator that is a concern in much of the Great Lakes region.[18] The spiny waterflea eats many native zooplankton, competing with native fish larvae; however due to their large spined tails they are less often consumed by larger fish. Although it has not been identified in the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage, the waterflea has been observed in nearby lakes such as Butternut Lake (Forest County WI) and the Gile Flowage (Iron County WI).[34] This species could be unintentionally spread to the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage by way of contaminated hulls or bilge tanks from boats, or on contaminated fishing line.[35]

Monitoring[]

Some lake management activities are undertaken by the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage & Trude Lake Property Owners Association, Inc.; in 2010, this group sponsored a grant to assess flowage water quality.[36] Additionally, the Iron County Land and Water Conservation Department[37] monitors, reports, and takes action against invasive species. At the flowage, the department has performed biological control of purple loosestrife with Galerucella calmariensis beetles and conducted surveys of boating practices at landings.[38][39]

Cultural Significance[]

Indigenous history[]

The lakes that would make up the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage all originally fell with in the territory of the Ojibwe.[40] The band now living in Lac du Flambeau settled the area in 1745 under the leadership of Azhedewish (Bad Pelican).[41][42]

It is mostly like the first Europeans in the region were French fur traders and trappers otherwise known as Coureur de Bois.[3]

In the Treaty of 1854 the Ojibwe officially ceded several territories in modern day Minnesota and Wisconsin including Iron County.[41][43][44] The Wisconsin State Constitution holds that all navigable waters in the state are considered public highways.[3] In this case the Flambeau River (and any land it floods) remain a matter of public trust.[45] Businesses and property owners such as the Chippewa and Flambeau Improvement Company: the company responsible for the damming of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage, do retain riparian rights.[45][3]

While the Turtle-Flambeau flowage post-dates the ceding of Ojibwe lands to the state of Wisconsin, it and the surrounding waterways have been the source of many treaty disputes. While the 1854 treaty allowed the Ojibwe to hunt and fish on ceded territory, the state of Wisconsin attempted to regulate these activities both on and off reservations.[46] In 1983, the U.S 7th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the tribes' right to fish and hunt in all ceded territories, not just reservations, in the Lac Court Oreilles v. Voigt, et al. case.[47] This led to a backlash from white residents; rocks were thrown at Ojibwe spearfishers on the flowage, and groups such as Stop Treaty Abuse-Wisconsin confronted Ojibwe at boat landings across the area.[48] Additionally, then-governor Tommy Thompson attempted to roll back the Ojibwe treaty rights, first through the court system and then by offering payments to different bands to suspend their harvest. Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner also introduced (unsuccessful) legislation in the U.S. House of representatives to ban tribal hunting and fishing on non-reservation lands.[46][49] Tribal walleye spearfishing on the Turtle-Flambeau flowage accounts for 25% of the total harvest in ceded territory, and overall impact on the fishery is minimal (3.6% of total walleye harvest on the flowage).[29]

Fishing[]

Many of the species of fish endemic to the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage are popular with anglers. Species including Walleye, Northern pike, and Muskellunge are popular trophy fish and therefore have an annual season to protect these species.[50][51] Other fish commonly found on the flowage include smallmouth bass, rock bass, bluegill, black crappie, and bullhead catfish.[52] The walleye population is especially robust, although estimated numbers declined from 72,967 fish ≥ 38 cm in 1989 to 54,208 fish ≥ 38 cm in 2009. [53]

While most individuals are only allowed to use rod and reel for fishing, members of Ojibwe people have the right to spearfish walleye (see above).[50]

Tourism and recreation[]

The Turtle-Flambeau Flowage is a major destination of summer tourism. Visitors have access to the lake from four public boat landings. Camping, hunting, and fishing are also popular activities. The Turtle-Flambeau Scenic Waters Area offers 60 remote campsites accessible by water only. These sites are available year-round on a first-come, first-served basis. There is no camping fee, but camping on the flowage is restricted to designated sites.

Historically, many lakeside resorts have existed in the vicinity of the flowage. However, today much of the shoreline remains sparsely developed.

See also[]

List of lakes in Wisconsin

External links[]

- Turtle-Flambeau Flowage & Trude Lake Property Owners Association

- Wisconsin Natural Resources article

References[]

- ^ "Wisconsin DNR website". Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Wisconsin DNR website". Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hittle, Michael (2018). An Accidental Jewel Wisconsin's Turtle-Flambeau Flowage. Mineral Point WI: . ISBN 978-1-942586-31-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Turtle-Flambeau Patterned Bog State Natural Area – Wisconsin DNR". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (2014). "Flambeau Flowage Watershed 2014 Water Quality Management Plan Update." http://dnr.wi.gov/water/wsSWIMSDocument.ashx?documentSeqNo=117706025

- ^ "Wisconsin Geological & Natural History Survey » Bedrock Geology of Wisconsin". wgnhs.wisc.edu. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Roth, Filbert (March 1910). "State Forests in Michigan". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 35 (2): 44–49. doi:10.1177/000271621003500206. S2CID 141143920 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Klase, Bill (May 14, 2018). "The soil between your toes". Woodland Info. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ "Turtle Flambeau Flowage". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Turtle Flambeau Flowage". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Home Turtle Flambeau Flowage Association". www.turtleflambeauflowage.com. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Hydro Level and Discharge Rates | Xcel Energy". www.xcelenergy.com. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Power Plants | Xcel Energy". www.xcelenergy.com. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Xcel Energy: Responsible by Nature". web.archive.org. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Water Detail – Turtle Flambeau Flowage, Upper North Fork Flambeau River,Flambeau Flowage Watershed (UC13, UC14)". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ "Turtle-Flambeau Scenic Waters Area" (PDF).

- ^ "Water quality study on Turtle Flambeau Flowage completed". The Lakeland Times. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wetzel, R.G. (2001). Limnology, 3rd Edition. New York: Academic Press.

- ^ "Turtle Flambeau Flowage – Townline Lake – Deep Hole". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Turtle Flambeau Flowage – Baraboo – Deep Hole". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Ewers, B. E. (July 2002). "Tree species effects on stand transpiration in northern Wisconsin". Water Resources Research. 38 (7): 8-1–8-11. Bibcode:2002WRR....38.1103E. doi:10.1029/2001WR000830 – via AGU.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Turtle-Flambeau-Manitowish Peatlands" (PDF).

- ^ "Project Detail". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "turtles of Wisconsin". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Belant, Jerrold (1991). "Common loon, Gavia immer, productivity on a northern Wisconsin impoundment". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 105: 29–33.

- ^ Belant, Jerrold (1993). "Evaluation of the Single Survey Technique for Assessing Common Loon Populations". Journal of Field Ornithology. 64: 77–83 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Groetsch, et al. (2003). " Investigations into Walleye Mercury Concentrations related to Long-Standing Reservoirs’ Water Quality, Wetlands and Federal Energy Regulatory Licensed Dam Operation." Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission. http://data.glifwc.org/archive.bio/Project%20Report%2003-02.pdf

- ^ Louis, V. L. S., et al. (1994). "Importance of Wetlands as Sources of Methyl Mercury to Boreal Forest Ecosystems." Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 51(5): 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1139/f94-106

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. "Fishery Management Plan Turtle-Flambeau Flowage, Iron County, Wisconsin March, 2007" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bithynia tentaculata". USGS. September 2019.

- ^ "Purple Loosestrife". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Volunteers Needed for our Annual Purple Loosestrife Survey – Turtle Flambeau Flowage & Trude Lake". Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "TFF Purple Loosestrife". Google My Maps. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Spiny Waterflea". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Muirhead, Jim (February 2005). "Development of Inland Lakes as Hubs in an Invasion Network". Journal of Applied Ecology. 42: 80–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2004.00988.x – via JSTOR.

- ^ "TURTLE FLAMBEAU FLOWAGE TRADE LAKE PROPERTY: Turtle Flambeau Flowage Water Quality Monitoring". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Iron County Land and Water Conservation Department".

- ^ Iron County Land and Water Conservation Department. "7/8/2015 data report".

- ^ Iron County Land and Water Conservation Department. "9/2/2019 Survey Report".

- ^ "Map". Wisconsin First Nations. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Valliere Jr, Leon (2004). Memories of Lac du Flambeau Elders: With a Brief History of Waaswaagoning Ojibweg. Madison WI: . pp. 9–76. ISBN 0-924119-21-7.

- ^ "Historical Timeline – Ojibwe Museum & Cultural Center". Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "1854 Treaty". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "1854: Ojibwe". treatiesmatter.org. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The public trust doctrine | Wisconsin DNR". dnr.wisconsin.gov. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Spearfishing Controversy | Milwaukee Public Museum". www.mpm.edu. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians,et al., Plaintiffs- Appellants, Cross-appellees, v. Lester P. Voigt, et al., Defendants-appellees, Cross-appellants.united States of America, Plaintiff-cross-appellee, v. State of Wisconsin, a Sovereign State, and Sawyer County,wisconsin, Defendants-cross-appellants, 700 F.2d 341 (7th Cir. 1983)". Justia Law. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Ina, Lauren (April 24, 1990). "WISCONSIN FIGHTS ANNUAL FISHING WAR". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Pierson, Brian (July 2009). "The Spearfishing Civil Rights Case: Lac Du Flambeau Band v. Stop Treaty Abuse-Wisconsin" (PDF). Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fishery of the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ "New Walleye Regulations For Turtle-Flambeau Flowage". dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (2020). "The Fishery of the Turtle Flambeau Flowage: Fish Population Status" (PDF).

- ^ Eslinger, L., & Lawson, Z. (January 2015). The History of Turtle-Flambeau Flowage Walleye: Maintaining a Sustainable Fishery Through a No-minimum Length Limit. Retrieved December 2020, from https://dnr.wi.gov/files/PDF/pubs/fh/ManageReports/FH155.pdf

- Reservoirs in Wisconsin

- Landforms of Iron County, Wisconsin

- Northern Wisconsin geography stubs