Vinpocetine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 56.6 +/- 8.9% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2.54 +/- 0.48 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.050.917 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

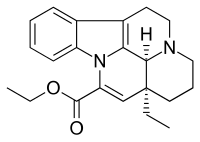

| Formula | C22H26N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 350.462 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| | |

Vinpocetine (ethyl apovincaminate) is a synthetic derivative of the vinca alkaloid vincamine. Vincamine is extracted from either the seeds of Voacanga africana or the leaves of Vinca minor (lesser periwinkle).

Medical uses[]

Vinpocetine has been used in many Asian and European countries for treatment of cerebrovascular disorders such as stroke and dementia for over three decades.[2] Vinpocetine is not approved for any therapeutic use in the United States.

The FDA has ruled that vinpocetine, due to its synthetic nature and proposed therapeutic uses, is ineligible to be marketed as dietary supplement under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[3][4][5][6] Despite this, vinpocetine remains widely available in dietary supplements often marketed as nootropics.[7][8][9][10]

The sale of vinpocetine as a supplement is banned in Australia and New Zealand due to "potential harmful nootropic characteristics".[11] Vinpocetine is legally sold in Canada. Refer to the Health Canada website, for more details. Vinpocetine does not fully support a benefit in either dementia or stroke.[12][8][13] As of 2003, three controlled clinical trials had tested "older adults with memory problems".[14]

Vinpocetine is licensed by Health Canada to be sold, as a supplement, for the following recommended uses: "to help improve cognitive function in those with age related cognitive decline,"[1] and "to improve memory and cognition,"[2] (in addition to other purposes/uses when taken in adjunction to other chemicals and/or herbs).

Side effects[]

Use during pregnancy may harm the baby or result in miscarriage.[1]

Adverse effects of vinpocetine include flushing, nausea, dizziness, dry mouth, transient hypo- and hyper-tension, headaches, heartburn, and decreased blood pressure.[7][15] FDA issued a statement in 2019 warning that "vinpocetine may cause a miscarriage or harm fetal development".[16] Vinpocetine has been implicated in one case in the induction of agranulocytosis,[17][unreliable medical source?] a serious condition in which granulocytes are markedly decreased. Some people have anecdotally noted that their continued use of vinpocetine reduces immune function. Commission E warned that vinpocetine-reduced immune function could cause apoptosis (cellular death) in the long term.[18]

Mechanism of action[]

Vinpocetine’s mechanism of action has been postulated to involve three potential effects: blockage of sodium channels, reduction of cellular calcium influx, and antioxidant activity.[13] Studies have also suggested that vinpocetine can inhibit PDE-1 in isolated rabbit aorta;[19] inhibit IKK in vitro, preventing IκB degradation and the following translocation of NF-κB to the cell nucleus;[20][21] and increase DOPAC, a metabolic breakdown product of dopamine, in isolated striatal nerve endings of rats.[22]

Dietary supplement[]

The inclusion of vinpocetine in dietary supplements in the U.S. has come under scrutiny due to the lack of defined dosage parameters, unproven short- and long-term benefits, and risks to human health.[11] In the U.S., vinpocetine supplements are marketed as sports supplements, brain enhancers, and weight loss supplements.[8]

A 2015 analysis of 23 brands of vinpocetine dietary supplements sold at GNC and Vitamin Shoppe retail stores reported widespread labeling errors.[3] Only 6 of the 23 supplement labels (26%) provided consumers with accurate dosages of vinpocetine (ranging from 0.3 to 32 mg per recommended daily serving), while 6 of 23 (26%) contained no vinpocetine at all, despite their labels claiming that the ingredient was in them.[8][7] In total, 9 of the 23 products tested were mislabeled and 17 of 23 (74%) did not provide any information on the quantity of vinpocetine.[7]

In response to the study, then-Senator Claire McCaskill, while at the time serving as the top Democrat on the Senate Special Committee on Aging, urged the FDA to suspend sales of vinpocetine supplements and asked 10 retailers to voluntarily stop selling vinpocetine products. McCaskill stated "The way we regulate these supplements isn’t working—and it’s putting the lives and well-being of consumers at risk. We’ve seen products with false labels, tainted ingredients, wildly illegal claims, and, now, products containing synthesized ingredients that are classified as prescription drugs in other countries."[10]

A 2016 analysis of eight brands of vinpocetine supplements sold in the U.S. found that the amount of vinpocetine contained was highly variable, ranging from 0.6 to 5.1 mg per serving, with most of the product labels providing no information on the amount of vinpocetine. Only one of the products tested contained the amount of vinpocetine that was specified on the label (1.070 mg per serving). The authors of the study noted that the lack of proper labeling regarding the amounts of vinpocetine in the products could pose a risk of adverse effects to consumers.[11]

Lawsuits[]

Procera AVH is a dietary supplement containing undisclosed amounts of vinpocetine in combination with huperzine A and acetyl-l-carnitine.[23][24] In 2012, manufacturer Brain Research Labs (BRL) agreed to pay $500,000 to settle a class action lawsuit which alleged that the company had falsely marketed Procera AVH as capable of improving brain function, in violation of the Consumer Fraud Act.[25]

In July 2015, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ruled that marketing claims for Procera AVH, which promoted the product as a “solution” to memory loss and cognitive decline, were false, misleading, unsubstantiated, and in violation of the FTC Act.[25][9][26][27] BRL and its affiliated companies, Brain Power Partners, Brain Power Founders, and MedHealth Direct (all based in Laguna Beach, California) were fined $91 million. KeyView Labs, the Tampa, Florida-based company that purchased BRL in 2012, was fined $61 million.[25][26][9][27] Also named in the FTC complaint were George Reynolds (aka Josh Reynolds), founder and chief science officer of BRL, and John Arnold, the sole officer and employee of MedHealth. The FTC complaint charged Reynolds with making deceptive expert endorsements for Procera AVH.[23][25][26][9][27] The defendants in the case ultimately agreed to pay $1.4 million to settle the allegations of deceptive advertising brought by the FTC and California law enforcement officials. In addition, a permanent injunction barred the defendants from making similar deceptive claims about Procera AVH in the future and from misrepresenting the existence, results, or conclusions of any scientific study.[26][9]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Commissioner, Office of the (3 June 2019). "Statement on warning for women of childbearing age about possible safety risks of dietary supplements containing vinpocetine". FDA. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Yi-shuai Zhanga, Jian-dong Lib, Chen Yana. "An update on vinpocetine: New discoveries and clinical implications".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmitt, Rick (January 12, 2017). "Marketers exploit the aged with unproven brain-health claims". Newsweek. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ Hank, Schulz. "FDA rules vinpocetine not a legal dietary ingredient despite successful NDI filings". NutraIngredients. William Reed Business Media, England. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ "FDA Concludes Vinpocetine Ineligible as a Dietary Ingredient". Nutraceuticals World. Rodman Media. September 20, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Schmitt, Rick (February 3, 2017). "Dubious doses". Newsweek. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Avula, Bharathi; Chittiboyina, Amar G.; Sagi, Satyanarayanaraju; Wang, Yan-Hong; Wang, Mei; Khan, Ikhlas A.; Cohen, Pieter A. (March 2016). "Identification and quantification of vinpocetine and picamilon in dietary supplements sold in the United States". Drug Testing and Analysis. 8 (3–4): 334–343. doi:10.1002/dta.1853. PMID 26426301.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cohen, Pieter A. (October 2015). "Vinpocetine: An Unapproved Drug Sold as a Dietary Supplement". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (10): 1455. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.008. PMID 26434971.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Supplement Marketers Will Relinquish $1.4 Million to Settle FTC Deceptive Advertising Charges". U.S. Federal Trade Commission. July 8, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erickson, Britt E. (October 31, 2016). "Vinpocetine: drug or dietary supplement?". Chemical & Engineering News. 94 (43): 16–17. ISSN 0009-2347. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c French JMT, King MD, McDougal, OM (2016). "Quantitative determination of vinpocetine in dietary supplements". Nat Prod Commun. 11 (5): 607–609. PMC 5345962. PMID 27319129.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Szatmari SZ, Whitehouse PJ (2003). "Vinpocetine for cognitive impairment and dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003119. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003119. PMC 8406981. PMID 12535455.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bereczki D; Fekete I (January 23, 2008). "Vinpocetine for acute ischaemic stroke (Review)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000480. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000480.pub2. PMC 7034523. PMID 18253980.

- ^ McDaniel MA, Maier SF, Einstein GO (2003). ""Brain-specific" nutrients: a memory cure?". Nutrition. 19 (11–12): 957–75. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(03)00024-8. PMID 14624946.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (September 2013). "Chemical Information Review Document for Vinpocetine (CAS No. 42971-09-5)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the (2019-06-03). "Statement on warning for women of childbearing age about possible safety risks of dietary supplements containing vinpocetine". FDA. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ Shimizu Y, Saitoh K, Nakayama M, Suto K, Raikohara R, Nemoto T. "Agranulocytosis induced by vinpocetine". Medicine Online. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (Germany) (1999). The Complete German Commission E monographs : therapeutic guide to herbal medicines (Reprint ed.). Austin, Tex.: American Botanical Council. ISBN 978-0-9655555-0-0.[page needed]

- ^ Hagiwara M, Endo T, Hidaka H (February 1984). "Effects of vinpocetine on cyclic nucleotide metabolism in vascular smooth muscle". Biochemical Pharmacology. 33 (3): 453–7. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90240-5. PMID 6322804.

- ^ Jeon KI, Xu X, Aizawa T, Lim JH, Jono H, Kwon DS, Abe J, Berk BC, Li JD, Yan C (May 2010). "Vinpocetine inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent inflammation via an IKK-dependent but PDE-independent mechanism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (21): 9795–800. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914414107. PMC 2906898. PMID 20448200.

- ^ Medina AE (June 2010). "Vinpocetine as a potent antiinflammatory agent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (22): 9921–2. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9921M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005138107. PMC 2890434. PMID 20495091.

- ^ Trejo F, Nekrassov V, Sitges M (August 2001). "Characterization of vinpocetine effects on DA and DOPAC release in striatal isolated nerve endings". Brain Research. 909 (1–2): 59–67. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02621-X. PMID 11478921. S2CID 38990597.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGrory, Kathleen (July 9, 2015). "Tampa diet supplement firm pays $1.4 million settlement over 'brain power' pill claims". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (September 18, 2012). "Procera AVH: A Pill to Restore Memory". Science Based Medicine. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Almada, Bianca (July 6, 2015). "False claims for brain supplement draw $152 million penalty from FTC". Orange County Register. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Procera AVH Marketers Can Forget About Claiming to Reverse Memory Loss". National Law Review. July 30, 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Myers, Steve (July 8, 2015). "Memory Supplement Marketers Settle FTC Case for $150M". Natural Products Insider. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Nootropics

- PDE1 inhibitors

- Vasodilators

- Ethyl esters

- Vinca alkaloids