Visegrád Group

show

Visegrád Group | |

|---|---|

The group's logo, representing the relative positions of the four countries' capital cities

| |

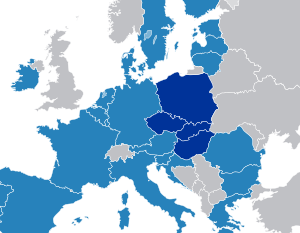

Visegrád Group countries Other member states of the European Union | |

| Membership |

|

| Leaders | |

| Poland | |

| Establishment | 15 February 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 533,615 km2 (206,030 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | |

• Density | 120.0/km2 (310.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

The Visegrád Group, Visegrád Four, V4, or European Quartet, is a cultural and political alliance of four countries of Central Europe[4] (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia), all of which are members of the EU and of NATO, to advance co-operation in military, cultural, economic and energy matters with one another and to further their integration to the EU.[5]

The Group traces its origins to the summit meetings of leaders from Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland held in the Hungarian castle town of Visegrád[6] on 15 February 1991. Visegrád was chosen as the location for the 1991 meeting as an intentional allusion to the medieval Congress of Visegrád in 1335 between John I of Bohemia, Charles I of Hungary and Casimir III of Poland.

After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, the Czech Republic and Slovakia became independent members of the group, thus increasing the number of members from three to four. All four members of the Visegrád Group joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.

Historical background[]

The name of the Group is derived and the place of meeting selected from the 1335 Congress of Visegrád held by the Bohemian (Czech), Polish, and Hungarian rulers in Visegrád. Charles I of Hungary, Casimir III of Poland, and John of Bohemia agreed to create new commercial routes to bypass the city of Vienna, a staple port, which required goods to be offloaded and offered for sale in the city before they could be sold elsewhere, and to obtain easier access to other European markets. The recognition of Czech sovereignty over the Duchy of Silesia was also confirmed. The second Congress took place in 1339 and decided that if Casimir III of Poland died without a son, which actually happened, the King of Poland would be the son of Charles I of Hungary, Louis I of Hungary.[7]

From the 1500s, large parts of the present-day countries became part of or were influenced by the Vienna-based Habsburg Monarchy until the end of World War I and the dissolution of the Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary. After World War II, the countries became satellite states of the Soviet Union, as the Polish People's Republic, the Hungarian People's Republic and the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. In 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe enabled the three countries to embrace capitalism and democracy. In December 1991, the fall of the Soviet Union would occur. The Visegrád Group was established on 15 February 1991.[7]

Economies[]

All four nations in the Visegrád Group are high-income countries with a very high Human Development Index. V4 countries have enjoyed more or less steady economic growth for over a century.[8] In 2009, Slovakia adopted the euro as its official currency and is the only member in the Group to do so.

If counted as a single nation state, the Visegrád Group's GDP would be the 4th in the EU and 5th in Europe[9] and 15th in the world.[10] Both in terms of exports and imports, the V4 is also at the forefront not only in Europe, but also in the world (4th in the EU, 5th in Europe and 8th in the world).[11]

Based on gross domestic product per capita (PPP) estimated figures for the year 2020, the most developed country in the grouping is the Czech Republic (US$40,858 per capita), followed by Slovakia (US$38,321 per capita), Hungary (US$35,941 per capita) and Poland (US$35,651 per capita). The average GDP (PPP) in 2019 for the entire group is estimated at around US$34,865.

Within the EU, the V4 countries are pro-nuclear-power, and are seeking to expand or found (in the case of Poland) a nuclear-power industry. They have sought to counter what they see as an anti-nuclear-power bias within the EU, believing their countries would benefit from nuclear power.[12][13]

Czech Republic[]

The economy of the Czech Republic is the group's second largest (GDP PPP of US$432.346 billion[14] total, ranked 36th in the world).

Within the V4, the Czech Republic has the highest Human Development Index,[15] Human Capital Index,[16] nominal GDP per capita[17] as well as GDP at purchasing power parity per capita.[18]

Hungary[]

Hungary has the group's third largest economy (total GDP of US$350.000 billion, 53rd in the world). Hungary was one of the more developed economies of the Eastern bloc. With about $18 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) since 1989, Hungary has attracted over one-third of all FDI in central and eastern Europe, including the former Soviet Union. Of this, about $6 billion came from American companies. Now it is an industrial agricultural state. The main industries are engineering, mechanical engineering (cars, buses), chemical, electrical, textile, and food industries. The services sector accounted for 64% of GDP in 2007 and its role in the Hungarian economy is steadily growing.[citation needed]

The main sectors of Hungarian industry are heavy industry (mining, metallurgy, machine and steel production), energy production, mechanical engineering, chemicals, food industry, and automobile production. The industry is leaning mainly on processing industry and (including construction) accounted for 29.32% of GDP in 2008.[19] The leading industry is machinery, followed by the chemical industry (plastic production, pharmaceuticals), while mining, metallurgy and textile industry seemed to be losing importance in the past two decades. In spite of the significant drop in the last decade, the food industry still contributes up to 14% of total industrial production and amounts to 7–8% of the country's exports.[20]

Agriculture accounted for 4.3% of GDP in 2008 and along with the food industry occupied roughly 7.7% of the labor force.[21][22]

Tourism employs nearly 150,000 people and the total income from tourism was 4 billion euros in 2008.[23] One of Hungary's top tourist destinations is Lake Balaton, the largest freshwater lake in Central Europe, with 1.2 million visitors in 2008. The most visited region is Budapest; the Hungarian capital attracted 3.61 million visitors in 2008. Hungary was the world's 24th most visited country in 2011.[24]

Poland[]

Poland has the region's largest economy (GDP PPP total of US$1.353 trillion,[25] ranked 22nd in the world). According to the United Nations and the World Bank, it is a high-income country[26] with a high quality of life and a very high standard of living.[27][28] The Polish economy is the sixth-largest in the EU and one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe, with a yearly growth rate of over 3.0% between 1991 and 2019. Poland is the only European Union member to have avoided a decline in GDP during the late-2000s recession, and in 2009 created the most GDP growth of all countries in the EU. The Polish economy had not entered recession nor contracted. According to Poland's Central Statistical Office, in 2011 the Polish economic growth rate was 4.3%, the best result in the entire EU. The largest component of its economy is the service sector (67.3%), followed by industry (28.1%) and agriculture (4.6%). Since increased private investment and EU funding assistance, Poland's infrastructure has developed rapidly.

Poland's main industries are mining, machinery (cars, buses, ships), metallurgy, chemicals, electrical goods, textiles, and food processing. The high-technology and IT sectors are also growing with the help of investors such as Google, Toshiba, Dell, GE, LG, and Sharp. Poland is a producer of many electronic devices and components.[29]

Slovakia[]

The smallest, but still considerably powerful V4 economy is that of Slovakia (GDP of US$209.186 billion total, 68th in the world).[30]

Demographics[]

The population is 64,301,710 inhabitants, which would rank 22nd largest in the world and 4th in Europe (very similar in size to France, Italy or the UK) if V4 were a single country. Most people live in Poland (38 million),[31] followed by the Czech Republic (nearly 11 million),[32] Hungary (nearly 10 million)[33] and Slovakia (5.5 million).[34]

V4 capitals[]

- Warsaw (Poland) – 1,790,658 inhabitants (metro – 3,105,883)

- Budapest (Hungary) – 1,779,361 inhabitants (metro – 3,303,786)

- Prague (Czech Republic) – 1,318,688 inhabitants (metro – 2,647,308)

- Bratislava (Slovakia) – 432,801 inhabitants (metro – 659,578)

Current leaders[]

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Andrej Babiš

Prime Minister

Hungary

Hungary

Viktor Orbán

Prime Minister

Poland

Poland

Mateusz Morawiecki

Prime Minister

Slovakia

Slovakia

Eduard Heger

Prime Minister

Initiatives[]

International Visegrad Fund[]

The International Visegrad Fund (IVF) is the only institutionalized form of regional cooperation of the Visegrad Group countries.

The main aim of the fund is to strengthen the ties among people and institutions in Central and Eastern Europe through giving support to regional non-governmental initiatives.[citation needed]

Defence cooperation[]

Visegrád Battlegroup[]

On 12 May 2011, Polish Defence Minister Bogdan Klich said that Poland will lead a new EU Battlegroup of the Visegrád Group. The decision was made at the V4 defence ministers' meeting in Levoča, Slovakia, and the battlegroup became operational and was placed on standby in the first half of 2016. The ministers also agreed that the V4 militaries should hold regular exercises under the auspices of the NATO Response Force, with the first such exercise to be held in Poland in 2013. The battlegroup included members of V4 and Ukraine.[35] Another V4 EU Battlegroup will be formed in the second semester of 2019.[36]

Other cooperation areas[]

On 14 March 2014, in response to the 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, a pact was signed for a joint military body within the European Union.[37] Subsequent Action Plan defines these other cooperation areas:[38]

- Defence Planning

- Joint Training and Exercises

- Joint Procurement and Defence Industry

- Military Education

- Joint Airspace Protection

- Coordination of Positions

- Communication Strategy

Visegrad Patent Institute[]

Created by an agreement signed in Bratislava on 26 February 2015, the Institute aims at operating as an International Searching Authority (ISA) and International Preliminary Examining Authorities (IPEA) under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) as from 1 July 2016.

Neighbor relations[]

European Union[]

All members of the V4 have been member states of the European Union since the EU's enlargement in 2004, and have been members of the Schengen Area since 2007.

Austria[]

Austria is the Visegrád Group's southwestern neighbor. The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Austria launched the Austerlitz format for the three countries in early 2015. The first meeting in this format took place on 29 January 2015 in Slavkov u Brna (Austerlitz) in the Czech Republic. Petr Drulák, the deputy foreign minister of the Czech Republic, emphasized that the Austerlitz format was not a competitor, but an addition to the Visegrád group.[39]

The leadership of the Freedom Party of Austria, the junior partner in the former Austrian coalition government, has expressed its willingness to closely cooperate with the Visegrád Group.[40] Chancellor and leader of the Austrian People's Party Sebastian Kurz wants to act as a bridge builder between the east and the west.[41]

Germany[]

Germany, Visegrad Group's western neighbor, is a key economic partner of the group and vice versa. As of 2018, Germany's trade and investment flows with the V4 are greater than with China.[42]

Romania[]

On 24 April 2015, Bulgaria, Romania and Serbia established the Craiova Group. The idea came from Victor Ponta, the then Romanian Prime Minister, who said he was inspired by the Visegrád Group.[43] Greece joined the group in October 2017.[44]

Romania has been invited to participate in the Visegrád Group on previous occasions. However, several Romanian politicians have viewed this possibility with skepticism, as the group's illiberal policies differ from Romania's more pro-European direction.[45]

Non-EU[]

Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia border Ukraine on their east. Poland additionally borders Belarus and Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast to the northeast. The Czech Republic is fully surrounded by other EU members. Hungary borders Serbia, a candidate for EU accession, in the south.

Ukraine[]

Ukraine, an eastern neighbor of the V4 that is not a member of the EU, is one of largest recipients of the International Visegrad Fund support and receives assistance from the Visegrad Group for its aspirations to European integration.[46] Ukraine joined the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU and therefore with the V4 in 2016.[47]

Country comparison[]

[citation needed]

| Name | Czech Republic | Hungary | Poland | Slovakia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official name | Czech Republic (Česká republika) | Hungary (Magyarország) | Republic of Poland (Rzeczpospolita Polska) | Slovak Republic (Slovenská republika) |

| Coat of arms |

|

|

|

|

| Flag | ||||

| Population | ||||

| Area | 78,866 km2 (30, 450 sq mi) | 93,028 km2 (35,919 sq mi) | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi) | 49,035 km2 (18,933 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 134/km2 (347.1/sq mi) | 105.9/km2 (274.3/sq mi) | 123/km2 (318.6/sq mi) | 111/km2 (287.5/sq mi) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Capital | ||||

| Largest City | ||||

| Official language | Czech (de facto and de jure) | Hungarian (de facto and de jure) | Polish (de facto and de jure) | Slovak (de facto and de jure) |

| First Leader | Bořivoj I, Duke of Bohemia (first historically documented Duke of Bohemia, 867–889) | Grand Prince Árpád (traditional first leader of tribal principality, 895–907)King St. Stephen (of Christian kingdom, 997–1038) | Duke Mieszko I (traditional first leader of unified state, 960–992) | Pribina (traditional ancestor, ?–861) |

| Current Head of Government | Prime Minister Andrej Babiš (ANO 2011; 2017–present) | Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (Fidesz; 1998–2002, 2010–present) | Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (Law and Justice; 2017–present) | Prime Minister Eduard Heger (Ordinary People (Slovakia); 2021–present) |

| Current Head of State | President Miloš Zeman (Party of Civic Rights; 2013–present) | President János Áder (Fidesz; 2012–present) | President Andrzej Duda (Law and Justice; 2015–present) | President Zuzana Čaputová (Progressive Slovakia; 2019–present) |

| Main religions | 44.7% undeclared, 34.5% irreligious, 10.5% Roman Catholic, 2% other Christians, 0.7% others | 38.9% Catholicism (Roman, Greek), 13.8% Protestantism (Reformed, Evangelical), 0.2% Orthodox, 0.1% Jewish, 1.7% other, 16.7% Non-religious, 1.5% Atheism, 27.2% undeclared | 87.58% Roman Catholic, 7.10% Opting out of answer, 1.28% Other faiths, 2.41% Irreligious, 1.63% Not stated | 62% Roman Catholic, 5.9% Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Slovakia, 3.8% Slovak Greek Catholic Church, 1.8% Reformed churches, 0.9% Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church, 0.3% Jehovah's Witnesses, 0.2% Evangelical Methodist, 10.6% not specified, 13.4% no religion |

| Ethnic groups | 64.3% Czechs, 25.3% unspecified, 5% Moravians, 1.4% Slovaks, 1.0% Ukrainians, 3.0% Other | 83.7% Hungarian, 3.1% Roma, 1.3% German, 14.7% not declared | 98% Poles, 2% other or undeclared | 80.7% Slovaks, 8.5% Hungarians, 2.0% Roma, 0.6% Czechs, 0.6% Rusyns, 0.1% Ukrainians, 0.1% Germans, 0.1% Poles, 0.1% Moravians, 7.2% unspecified |

| GDP (nominal) | ||||

| External debt (nominal) | $77.786 billion (2019 Q2) – 31.6 % of GDP | $112.407 billion (2019 Q2) – 66.6 % of GDP | $281.812 billion (2019 Q2) – 47.5 % of GDP | $51.524 billion (2019 Q2) – 46.9 % of GDP |

| GDP (PPP) | ||||

| Currency | Czech koruna (Kč) – CZK | Hungarian forint (Ft) – HUF | Polish złoty (zł) – PLN | Euro (€) – EUR |

| Human Development Index |

See also[]

Other groups in Central Europe[]

- Bucharest Nine

- Central European Defence Cooperation

- Central European Initiative

- Salzburg Forum

- Three Seas Initiative

Similar groups[]

Other[]

- Central Europe

- International Visegrád Day

- Pact of Free Cities

References[]

- ^ "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "The Visegrad Group: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia | About the Visegrad Group". 15 August 2006.

- ^ "The Bratislava Declaration of the Prime Ministers of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Poland and the Slovak Republic on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Visegrád Group". Official web portal of the Visegrád Group. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014.

- ^ Engelberg, Stephen (17 February 1991). "Three Eastern European Leaders Confer, Gingerly". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A visegrádi négyek és az új évezred kihívásai - Vélemény - Szabadság". archivum2.szabadsag.ro.

- ^ "Aggregate And Per Capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000: Continental, Regional and National Data With Changing Boundaries, Stephen Broadberry University of Warwick" (PDF). Dev3.cepr.org. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ ""The Visegrád Group – Growth Engine of Europe"" (PDF).

- ^ "List of Countries by GDP (PPP)".

- ^ Workman, Daniel. "World's Top Export Countries". www.worldstopexports.com.

- ^ "Visegrád group backs nuclear energy". China.org.cn. 14 October 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Don't impede our nuclear, V4 tells EU". World-nuclear-news.org. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "V4". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2019 – "Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century"" (PDF). HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Human Capital Index 2018" (PDF).

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". World Economic Outlook. International Monetary Fund. October 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019, International Monetary Fund. Database updated in April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Elemzői reakciók az ipari termelési adatra (Analysts' Reaction on Industrial Production Data)" (in Hungarian). 7 April 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Food Industry". Itdh.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Value and distribution of gross value added by industries". Hungarian Central Statistical Office. 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Number of employed persons by industries". Hungarian Central Statistical Office. 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Táblamelléklet (Tables)" (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "UNWTO World Tourism Barometer" (PDF). World Tourism Organisation. January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Country and Lending Groups | Data". World Bank. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "SPI PROGRESS INDEX 2015". Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Quality of Life Index by Country 2017 Mid-Year". Numbeo.com. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Toshiba Invests in a Subsidiary of LG.Philips LCD in Poland. eCoustics.com (10 October 2006). Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ "IMF – International Monetary Fund Home Page". Imf.org.

- ^ "Wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2011" [Results of the 2011 National Census of Population and Housing] (PDF) (in Polish). 16 January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Czech Republic Population 2016". World Population Review. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "2011. ÉVI NÉPSZÁMLÁLÁS : 3. Országos adatok" (PDF). Ksh.hu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Visegrad grounds of Ukraine. Mirror Weekly. 13 May 2011 (in Ukrainian)

- ^ "Bratislava Declaration of the Visegrád Group Heads of Government on the Deepening V4 Defence Cooperation". Visegradgroup.eu. Visegrád Group. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Today's Stock Market News and Analysis". NASDAQ. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Visegrad Group Defence Cooperation". Visegrad Group. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ Schubert, Gerald (11 April 2015). "Österreich, Tschechien, Slowakei: Gemeinsame Politik im Austerlitz-Format". Der Standard (in German).

- ^ Stephan Löwenstein. Zwischen Wien und Budapest. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Published on 15 October 2017.

- ^ Alexe, Dan (1 February 2018). "Kurz and Orban want to clip Brussels' power, but Austria will not join Visegrad Four". New Europe. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Germany’s troubled relations with the Visegrad states show the limits to its power. The Economist. 14 June 2018.

- ^ "Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia Establish Craiova Group for Cooperation". Novinite. 24 April 2015.

- ^ Bochev, Venelin (6 December 2018). "Craiova Group – too late or better late than never?". European Policy Centre.

- ^ Touma, Ana Maria (10 October 2017). "Romania's Flirtation With Visegrad States Alarms Experts". Balkan Insight.

- ^ Claudia Patricolo. Ukraine looks to revive V4 membership hopes as Slovakia takes over presidency. emerging-europe.com. 29 July 2018.

- ^ EU-Ukraine free trade 'set for 2016' – President Poroshenko. BBC News. 17 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Visegrád Group. |

- 1991 in Europe

- 20th-century military alliances

- Bottom-up regional groups within the European Union

- Central European intergovernmental organizations

- Czech Republic–Hungary relations

- Czech Republic–Poland relations

- Czech Republic–Slovakia relations

- Hungary–Poland relations

- Hungary–Slovakia relations

- Poland–Slovakia relations

- European integration

- Foreign relations of the Czech Republic

- Foreign relations of Hungary

- Foreign relations of Poland

- Foreign relations of Slovakia

- Intergovernmental organizations

- International political organizations