Zhiduo (clothing)

| Zhiduo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zhiduo, a man's casual robe, after medieval China | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 直裰 or 直掇 or 直綴 or 直敠 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Straight gathering | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 直身 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Straight body | ||||||

| |||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 海青 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Ocean blue | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 직철 | ||||||

| Hanja | 直裰 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 直綴 | ||||||

| Hiragana | じきとつ | ||||||

| |||||||

Zhiduo (Chinese: 直裰, 直掇, 直綴 and 直敠; lit. 'straight gathering'[1]), also known as zhishen (Chinese: 直身; lit. 'straight body')[1] when the robe was decorated with outside pendulums,[2] and haiqing[3] (Chinese: 海青; lit. 'ocean blue' when referring to the long black/yellow Buddhist monk's robe), refers to two traditional Chinese man's outer robes: casual zhiduo and priests’ zhiduo, in the broad sense.[4] Particularly the former in the narrow sense.[5] Nowadays, the haiqing is sometimes referred as daopao.[6] In present days Taiwan, the haiqing is also worn by Zhenyi taoist priests.[7] In Japan, zhiduo was pronounced jikitotsu (直綴; じきとつ).[8] In Korea, zhiduo was pronounced as jikcheol (直裰);[9] it was also referred as the buddhist monk's jangsam (長衫/장삼) and was worn under the kasaya until the early Joseon period.[10] The zhiduo follows the structure of shenyi, which is Chinese traditional clothing.[9]

History[]

China[]

The Buddhist monk's zhiduo was worn as early as the Tang dynasty.[11] After the middle Tang dynasty, the zhiduo was worn together with the right bare cassock (i.e. kesa (Chinese: 袈裟; pinyin: jiasha); i.e. the one-piece rectangular robe); this form of dress became the standard dressing style for Buddhist monks and continued to prevail in the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties with little changes in styles.[11] The practice of wearing kesa on top of zhiduo then spread to Korea and Japan.[12] During the early Qing dynasty, the Qing court issued the tifa yifu (Chinese: 剃发易服) policies on the Han Chinese people which led to the disappearance of most hanfu.[13] The zhiduo was however spared from this policy.[13] In the Qing dynasty, the right bare cassock stopped being used and the Buddhist monk's zhiduo was used alone.[11]

Origins of zhiduo[]

When Buddhism was introduced in China during the Han dynasty around 65 AD,[14] the Indian Kasaya was also introduced.[15] The Indian Kasaya was composed of the sanyi (Chinese: 三衣; pinyin: sānyī; lit. 'three robes').[14][16] However, the Indian Kasaya was not well-received in China as the Chinese deeply believed in the Confucian concept of propriety; and as a result, any forms of body exposure was perceived as being improper and was associated with barbarians.[17] Being fully clothed is an expression of Chinese clothing culture, and compared to their Indian counterparts, the Chinese did not perceive the exposure of shoulders as a sign of respect.[14] The absence of right shoulder exposure started in northern China in order to shield the body from the cold and to fulfill the Chinese cultural requirements.[14] This change occurred during the Chinese medieval era with the bareness completely disappearing in the Cao Wei period.[14] It appears that shoulder exposure reappeared during the Northern Wei period before being criticized:[16]

People from the West in general have their arms uncovered. [Monks] were afraid that criticism of this practice would arise, and so the arm needed to be covered.... In the Northern Wei period, people from the Palace saw the bared arm of the monks. They thought this was inappropriate. Then a right sleeve was added, both sides of which were sewn. It was called pianshan. It was open from the collar in the front, so the original appearance was maintained. Therefore, it is known that the left part of the pianshan was actually just the inner robe, while the right part is to cover the shoulder.

— Yi, Lidu, Yungang Art, History, Archaeology, Liturgy, Zengxiu jiaoyuan qinggui

To create the pianshan (Chinese: 偏衫; called hensam in Japan[18] and pyeonsam (褊衫) in Korea[9]), which is a short robe, the monks combined the Saṃkakṣikā (Chinese: 僧祗支; pinyin: sengqi yi; i.e.the inner garment worn by both monks and nuns under the sanyi) and the Buddhist's nuns hujian yi (Chinese: 䕶肩衣).[17] The hujian yi was a piece of fabric which covers the right shoulder of Buddhist nuns; it started to be used after some Buddhist nuns suffered harassment by men for wearing right shoulder-exposing clothes.[17]

The zhiduo originated from the combination of the pianshan and a skirt (裙, qun).[17][18] Buddhist monks initially wore the pianshan as upper garment called pianshan (lit. 'side clothes') along with a skirt as a lower garment.[17][19][9] In accordance to the philosophy of Confucianism and Taoism, the use of upper and lower garment represented the heaven and earth which interacts in harmony.[14] This style of dress was imitated until the Tang dynasty until the lower and upper garment was joined together as a single, one-piece long garment.[14] By the time of the Yuan dynasty, this one-piece, long robe was termed zhiduo.[17] The term zhiduo can be found in a 1336 AD monastic code called the (simplified Chinese: 勅修百丈清規; traditional Chinese: 勅修百丈淸規; pinyin: Chixiu Baizhang qinggui).[17]

Origins of casual zhiduo[]

According to Shen Congwen's "Research on Ancient Chinese costumes" (Chinese: 中国古代服饰研究), the zhiduo evolved from the zhongdan (Chinese: 中襌 or 中单; i.e. an inner garment) which was worn by ancient monks.[13] Initially the zhiduo was mostly worn by monks, but in the Song dynasty and in the subsequent dynasties, it became a form of daily clothing for Han Chinese men.[13]

Origins of haiqing[]

Modern-day buddhist monks refer to that long Buddhist robe as haiqing (Chinese: 海青).[20] The wearing of long robes by Buddhist monks is a legacy of the Tang and Song period.[20] During the Tang and Song period, the Indian-style Kasaya went through major changes and do not have the same style of as the original Kasaya anymore.[20] The haiqing has some traces of traditional Chinese culture and shows some glimpse of the dress worn by the elites in ancient China.[20] Haiqing originated from the clothing style of the Han and Tang dynasties.[14] The form of right opening of the haiqing was passed down from the Shang dynasty.[14]

Japan[]

In Japan, the zhiduo was known as jikitotsu (直綴; じきとつ).[18][8] It is also known as koromo.[21][22] The koromo is worn by Japanese Buddhist monks or priests; the robe is typically black or blue.[23] A kesa is worn on top of the koromo.[23]

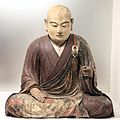

Portrait of a monk, Japan, 16th century.

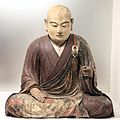

Portrait of Zen master Kyūzan Sōei (1605–1656).

Korea[]

In korea, the zhiduo was known as jikcheol (直裰).[9] During the Three Kingdoms period, Buddhism was introduced to Korea through China, and the Korean Buddhist monks wore Chinese style Buddhist robes.[24]

Up until the early period of Joseon, the Buddhist jangsam (長衫/장삼) which was worn under the kasaya was in the form of the jikcheol.[10] The Buddhist monk's jangsam was worn as early as the Goryeo period.[24]

There are two types of Buddhist jangsam which is worn as monastic robe in present days, the jangsam of the Jogye Order and the Taego Order of Buddhism.[24] The jangsam of the Jogye Order has structural similarities with the jikcheol from China whereas the one from the Taego Order is more structurally similar to the traditional durumagi.[24] The jikcheol developed in one of the current Korean, long-sleeved Buddhist Jangsam.[9] A form of present days Buddhist Jangsam was developed through the combination of the dopo's wide sleeves with the form of the durumagi (aka Juui, a coat with no vents).[10]

The Buddhist jangsam was also adopted as the shaman robe in Jeseokgeori.[24]

Types of Zhiduo[]

Casual zhiduo[]

The casual zhiduo was popular among men of the Song,[25] Yuan and Ming dynasties, it could be worn by both scholar-official and the common people, and has several features:[4]

- The bottom of robe reaches below the knee

- With overlapping collar

- A through center back seam runs down the robe

- With lateral slit on each lower side

- Without hem or lan (襴; a decorative narrow panel encircling the robe, usually held in position below the knee)

- Casual zhiduo

Su Shi in zhiduo

A Ming dynasty portrait illustrating a man wearing zhiduo, woman wearing banbi.

Ming dynasty portrait of men wearing zhiduo

Ming dynasty portrait of men wearing zhiduo

Matteo Ricci in zhiduo

Priests’ zhiduo[]

The priests’ zhiduo was generally worn by a Mahāyāna or Taoist priest, it had been popular since the Song dynasty, and has another several features:[4]

- With loose cuffs

- With black borders around the edges of robe

- With a lan on the waistline of robe

Haiqing[]

The haiqing has the following features:[6]

- The sleeves are wide and loose which makes it comfortable to wear

- The waist and lower hem are also wide and loose

Nowadays, haiqing are found in two colours:[6]

- In black colour - it is worn by most followers of Buddhism when they homage to the Buddha.

- It can also be found in yellow when it is worn by abbot of a temple or by a monastic who is officiating during a Dharma service.

- Haiqing

Chinese Buddhist monk's yellow robe

Taiwanese Buddhist nun's black robes.

See also[]

- Han Chinese clothing

- List of Han Chinese clothing

- Daopao

References[]

- ^ a b Burkus, Anne Gail (2010). Through a forest of chancellors : fugitive histories in Liu Yuan's Lingyan ge, an illustrated book from seventeenth-century Suzhou. Yuan, active Liu. Cambridge, Mass. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-68417-050-0. OCLC 956711877.

- ^ Zujie, Yuan (2007-01-01). "Dressing for power: Rite, costume, and state authority in Ming Dynasty China". Frontiers of History in China. 2 (2): 181–212. doi:10.1007/s11462-007-0012-x. ISSN 1673-3401.

- ^ "Chinese Man Costume | Ming Style Hanfu Outerwear: Zhishen". www.newhanfu.com. 2020. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ a b c 汛·周; 周汛; 高春明 (1996). 中国衣冠服饰大辞典 (in Chinese). pp. 158–9. ISBN 9787532602520.

- ^ Zhu, Heping (2001). 中国服饰史稿 (in Chinese). pp. 222–3. ISBN 9787534820496.

- ^ a b c "Hsingyun.org - Dharma Instrument: Haiqing". hsingyun.org. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Pregadio, Fabrizio (2012). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. 2. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781135796334.

- ^ a b 第三版,世界大百科事典内言及, ブリタニカ国際大百科事典 小項目事典,デジタル大辞泉,世界大百科事典 第2版,大辞林. "直綴(じきとつ)とは - コトバンク". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ^ a b c d e f 신공스님(허훈) (2006). "淸規에 나타난 僧伽服飾에 대한 考察". 禪學(선학) (in Korean). 13: 9–45. ISSN 1598-0588.

- ^ a b c "Seungbok(僧服)". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture.

- ^ a b c "The Slanted Shirt and the Zhiduo--《Studies on the Cave Temples》2011年00期". en.cnki.com.cn. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Zen and material culture. Pamela D. Winfield, Steven Heine. New York, NY. 2017. ISBN 978-0-19-046931-3. OCLC 968246492.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d 越, 檀之 (2012). "华夏衣冠之直裰与直身 [abstract]". 贵阳文史. 6: 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cheng, Fung Kei (2020-07-28). "Intertwined Immersion: The Development of Chinese Buddhist Master Costumes as an Example". Religious Studies. 8 (1): 23–44. ISSN 0536-2326.

- ^ Kieschnick, John (2003). The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture. Princeton. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-691-21404-7. OCLC 1159003372.

- ^ a b Yi, Lidu (2017). Yungang : art, history, archaeology, liturgy. New York. ISBN 978-1-351-40240-8. OCLC 990183288.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yifa (2002). The origins of Buddhist monastic codes in China : an annotated translation and study of the Chanyuan qinggui. Zongze. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-585-46406-5. OCLC 52763904.

- ^ a b c Waddell, N. A.; Waddell, Norman (1978). "Dōgen's Hōkyō-ki PART II". The Eastern Buddhist. 11 (1): 66–84. ISSN 0012-8708. JSTOR 44361500.

- ^ Buddhism and medicine : an anthology of Premodern sources. C. Pierce Salguero. New York. 2017. ISBN 978-0-231-54426-9. OCLC 978351922.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b c d Nan, Huaijin (1997). Basic Buddhism : exploring Buddhism and Zen. Huaijin Nan. York Beach, Me.: Samuel Weiser. ISBN 978-1-60925-453-7. OCLC 820723154.

- ^ "Robe Worn by a Zen Buddhist Mendicant Monk (Koromo or Jikitotsu) | RISD Museum". risdmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ Baroni, Helen Josephine (2002). The illustrated encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. p. 196. ISBN 0-8239-2240-5. OCLC 42680558.

- ^ a b "Koromo - Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia". tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e "Jangsam (長衫)". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture.

- ^ "直裰_知网百科". xuewen.cnki.net. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- Chinese traditional clothing