Aigues-Mortes

Aigues-Mortes | |

|---|---|

City walls | |

Coat of arms | |

show Location of Aigues-Mortes | |

Aigues-Mortes | |

| Coordinates: 43°34′03″N 4°11′36″E / 43.5675°N 4.1933°ECoordinates: 43°34′03″N 4°11′36″E / 43.5675°N 4.1933°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Occitanie |

| Department | Gard |

| Arrondissement | Nîmes |

| Canton | Aigues-Mortes |

| Intercommunality | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Pierre Mauméjean[1] |

| Area 1 | 57.78 km2 (22.31 sq mi) |

| Population (Jan. 2018)[2] | 8,456 |

| • Density | 150/km2 (380/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 30003 /30220 |

| Elevation | 0–3 m (0.0–9.8 ft) (avg. 1 m or 3.3 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Aigues-Mortes (French pronunciation: [ɛɡmɔʁt]; Occitan: Aigas Mòrtas) is a commune in the Gard department in the Occitanie region of southern France. The medieval city walls surrounding the city are well preserved. Situated on the junction of the Canal du Rhône à Sète and the Chenal Maritime to , the town is a transit center for canal craft and Dutch barges.[3] [4]

Toponymy[]

The name "Aigues-Mortes" was attested in 1248 in the Latinized form Aquae Mortuae, which means "dead water", or "stagnant water". The name comes from the marshes and ponds that surround the village (which has never had potable water). The inhabitants of the commune are known as Aigues-Mortais or Aigues-Mortaises.[5]

The Occitan Aigas Mortas is equivalent to toponymic types in the Morteau Oil dialect cf. Morteau (Doubs): mortua Aqua (1105, VTF521)[clarification needed] and Morteaue (Haute-Marne): mortua Aqua (1163, VTF521). Grau du Roy in French means "pond of the King". In Occitan, grau means "pond with extension".

History[]

Antiquity[]

The Roman general Gaius Marius is said to have founded Aigues-Mortes around 102 BC, but there is no documentary evidence to support this.

A Roman by the name of Peccius cultivated the first salt marsh and gave his name to the Marsh of Peccais.[6] Salt mining started from the Neolithic period and was continued in the Hellenistic period, but the ancient uses of saline have not resulted in any major archaeological discovery. It is likely that any remains were destroyed by modern saline facilities.[7]

Middle Ages[]

In 791, Charlemagne erected the amid the swamps for the safety of fishermen and salt workers. Some argue that the signaling and transmission of news was not foreign to the building of this tower which was designed to give warning in case of arrival of a fleet, as for the at Nîmes.

The purpose of this tower was part of the war plan and spiritual plan which Charlemagne granted at the Benedictine abbey, dedicated to Opus Dei (work of God) and whose incessant chanting, day and night, was to designate the convent as Psalmody or Psalmodi. This monastery still existed in 812, as confirmed by an act of endowment made by the Badila from Nîmes at the abbey.[8]

At that time, the people lived in reed huts and made their living from fishing, hunting, and salt production from several small salt marshes along the sea shore. The region was then under the rule of the monks from the Abbey of Psalmody.

In 1240, Louis IX, who wanted to get rid of the dependency on the Italian maritime republics for transporting troops to the Crusades, focused on the strategic position of his kingdom. At that time, Marseille belonged to his brother Charles of Anjou, King of Naples, Agde to the Count of Toulouse, and Montpellier to the King of Aragon. Louis IX wanted direct access to the Mediterranean Sea. He obtained the town and the surrounding lands by exchange of properties with the monks of the abbey. Residents were exempt from the salt tax which was previously levied so that they could now take the salt unconstrained.[9]

He built a road between the marshes and built the to serve as a watchtower and protect access to the city. Louis IX then built the on the site of the old Matafère Tower, to house the garrison. In 1272, his son and successor, Philip III the Bold, ordered the continuation of the construction of walls to completely encircle the small town. The work would not be completed for another 30 years.

This was the city from which Louis IX twice departed for the Seventh Crusade in 1248 and for the Eighth Crusade in 1270, where he died of dysentery at Tunis.

The year 1270 has been established, mistakenly for many historians, as the last step of a process initiated at the end of the 11th century. The judgment is hasty because the transfer of crusaders or mercenaries from the harbour of Aigues-Mortes continued after this year. The order given in 1275 to Sir Guillaume de Roussillon by Philip III the Bold and Pope Gregory X after the Council of Lyons in 1274 to reinforce Saint-Jean d'Acre in the East shows that maritime activity continued for a ninth crusade which never took place.[10]

There is a popular belief that the sea reached Aigues-Mortes in 1270. In fact, as confirmed by studies of the engineer Charles Leon Dombre, the whole of Aigues-Mortes, including the port itself, was in the Marette pond, the Canal-Viel and Grau Louis, the Canal Viel being the access channel to the sea. The Grau-Louis was approximately at the modern location of La Grande-Motte.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Philip the Fair used the fortified site to incarcerate the Templars. Between 8 and 11 November 1307, forty-five of them were put to the question, found guilty, and held prisoner in the Tower of Constance.[11]

Modern and contemporary periods[]

Aigues-Mortes still retained its privileges granted by the kings.[12] Curiously it was a great Protestant in the person of Jean d'Harambure "the One-Eyed", light horse commander of King Henry IV and former governor of Vendôme who would be appointed governor of Aigues-Mortes and the Carbonnière Tower on 4 September 1607. To do this, he took an oath before the Constable of France Henri de Montmorency, Governor of Languedoc, who was a Catholic and supported the rival Adrien de Chanmont, the Lord of Berichère. The conflict continued until 1612, and Harambure, supported by the pastors of Lower Languedoc and the inhabitants, finished it by a personal appeal to the Queen.[13] He eventually resigned on 27 February 1615 in favour of his son Jean d'Harambure, but King Louis XIII restored him for six years. On 27 July 1616 he resigned again in favour of Gaspard III de Coligny, but not without obtaining a token of appreciation for the judges and consuls of the city.

At the beginning of the 15th century, important works were being undertaken to facilitate access to Aigues-Mortes from the sea. The old Grau-Louis, dug for the Crusades, was replaced by the Grau-de-la-Croisette and a port was dug at the base of the Tower of Constance. It lost its importance from 1481 when Provence and Marseille were attached to the kingdom of France. Only the exploitation of the Peccais salt marshes encouraged François I, in 1532, to connect the salt industry of Aigues-Mortes to the sea. This channel, called Grau-Henry, silted up in turn. The opening, in 1752, of the Grau-du-Roi solved the problem for a while. A final solution was found in 1806 by connecting the Aigues-Mortes river port through the Canal du Rhône à Sète.[14]

The Canal du Rhône à Sète traversing Aigues-Mortes

Letter from Mr. Fargeon, administrator of the Canal of Aigues-Mortes, 25 November 1806

The canal du Rhône à Sète in 1915

From 1575 to 1622, Aigues-Mortes was one of the eight safe havens granted to the Protestants. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 caused severe repression of Protestantism, which was marked in Languedoc and the Cévennes in the early 18th century by the Camisard War. Like other towers in the town, from 1686 onwards, the Constance Tower was used as a prison for the Huguenots who refused to convert to Roman Catholicism. In 1703, Abraham Mazel, leader of the Camisards, managed to escape with sixteen companions.[citation needed]

During the French Revolution, the city was called Port-Pelletier.[15] At that time the port had almost disappeared due to silting, induced by the intensification of labour in the watershed at the same time as the clearing of woods and forests following the abolition of privileges. The decline of forest cover led to soil erosion and consequently a greater quantity of alluvial deposits in the ports of the region. Thus, in 1804 the prefect "Mr. de Barante père" wrote in a report[16] that: "The coasts of this department are more prone to silting ... The ports of Maguelonne and Aigues Mortes and the old port of Cette no longer exist except in history" he alerted: "An inordinate desire to collect and multiply these forest clearings since 1790 ... Greed has devoured in a few years the resource of the future, the mountains, opened to the plough, show that soon naked and barren rock, each groove becoming a ravine; the topsoil, driven by storms, has been brought into the rivers, and thence into the lower parts, where it serves every day to find the lowest parts and the darkest swamps."

The massacre of Italians (August 1893)[]

In the summer of 1893, the Compagnie des Salins du Midi launched a recruiting campaign for workers for the threshing and the lifting of salt. Hiring was reduced due to the economic crisis that hit Europe, so the prospect of finding a seasonal job was attractive in this year and there were a greater number of workers looking for work. These were divided into three categories nicknamed:

- "Ardèche" peasants, not necessarily native to Ardèche, who leave their land at this time of the season;

- "Piedmontese" consisting of Italians from throughout northern Italy and locally recruited by team leaders: the chefs du colle;

- "tramps" composed mainly of vagabonds.[17]

Because of the recruitment operated by Compagnie des Salins du Midi, the chefs de colle were forced to compose teams including both French and Italians.[18] In the early morning of 16 August 1893 a fight broke out between the two communities that quickly turned into a struggle of honour.[19] Despite the intervention of the justice of the peace and the police, the situation rapidly degenerated.[20] Some tramps met in Aigues-Mortes and, saying that Italians had killed some Aiguemortais, swelled the ranks of the population and of people who had not managed to find employment.[20] A group of Italians was then attacked and tried to take refuge in a bakery that rioters wanted to burn. The prefect called for troops at 4am, but they did not arrive on the scene until 18 hours after the drama.[21]

Early in the morning, the situation escalated and the rioters moved to the Peccais saltfields where there were the largest number of Italians. Police Captain Cabley, trying to provide protection, promised the rioters to hunt the Italians and escort them to the Aigues-Mortes Police Station.[22] It was during the journey that the Italians attacked by the rioters were massacred by a crowd that the police were unable to contain. There were seven dead and fifty wounded, some of whom had lifelong consequences.[23][24] This was the largest massacre of immigrants in the modern history of France and also one of the biggest scandals in its judicial history[25] because no condemnation was ever pronounced.

The case became a diplomatic issue and the transalpine (Italian) foreign press took up the cause of the Italians.[26] There were Anti-French riots in Italy.[27] A diplomatic solution was found and the parties were compensated[28] while the nationalist mayor Marius Terras was forced to resign.[29]

A theatrical play by Serge Valletti called Dirty August is based on the tragic events.

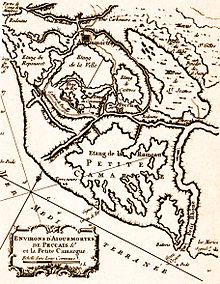

Geography[]

Aigues-Mortes is located in the Petite Camargue some 90 km (56 miles) northwest of Marseille. By road, Aigues-Mortes is about 33 km (21 miles) southwest of Nîmes, and 20 km (12 miles) east of Montpellier in a direct line. Access to the commune is by route D979 coming south from Saint-Laurent-d'Aigouze to Aigues-Mortes town. Route D979 continues southwest through the commune to Le Grau-du-Roi. Route D62 also starts from Aigues-Mortes heading southwest parallel to D979 before turning eastwards and forming part of the southern border of the commune. Route D62A continues to Plan d'Eau du Vidourie.

The commune is composed of a portion of the wet plains and lakes of the Petite Camargue. It is separated from the Gulf of Lions (and, thus, the Mediterranean) by the town of Le Grau-du-Roi, however Aigues-Mortes is connected to the sea through the Canal du Rhône à Sète. There is only one other hamlet in the commune called Mas de Jarras Listel on the western border.

The Canal du Rhône à Sète enters the commune from the northwest and the northeast in two branches from the main canal to the north and the branches intersect in the town of Aigues-Mortes before exiting as a single canal alongside route D979 and feeding into the Mediterranean Sea at Le Grau-du-Roi.[30]

A rail branch line from Nîmes passes through Aigues-Mortes from north-east to south-west, with a station in the town of Aigues-Mortes, to its terminus on the coast at Le-Grau-du-Roi. This line also transports sea salt.

The communes of Saint-Laurent-d'Aigouze and Le Grau-du-Roi are adjacent to the town of Aigues-Mortes. Its inhabitants are called Aigues-Mortais or Aigues-Mortise; in Occitan they are aigamortencs.

Aigues-Mortes is one of 79 member communes of the Schéma de cohérence territoriale (SCoT) of South Gard and is also one of 34 communes in the Pays Vidourle-Camargue. Aigues-Mortes is one of the four communes of the of SCoT in the South of Gard.

Heraldry[]

|

Blazon: Or, Saint Martin carnation clothed Azure in his right hand a sword argent pointing sinister chief cutting his cloak of gules mounted on a horse the same standing saddled in Or bridled the same with a lame pauper carnation to sinister right arm extended dexter chief half clothed in azure with crutch proper all on a Terrace in base Vert.

|

Economy[]

Agriculture[]

- Viticulture and asparagus[31]

- Breeding of bulls and of Camargue horses. Both are raised almost wild in the surrounding marshes.

- The Camargue bull is smaller than the Spanish fighting bulls, stocky, with high horns and head. It measures about 1.40 m at the withers. It is primarily intended for bullfighting which is very popular in the region.

- The Camargue horse is the ultimate companion for herdsmen to move into the marshes and herd bulls. According to some discoveries of bones, it seems that the ancestors of the Camargue horse date to the Quaternary period. The Camargue horse is not very large, about 1.50 m tall. It has a huge resistance adapted to the terrain. Its colour is brown at birth, gradually turning white after a few years.

Industries[]

- Production of salt by the operation of the saltworks of the Salins group. Probably used since ancient times, the salt of Aigues-Mortes attracted fishermen and salt workers. The Benedictine monks settled nearby in the 8th century at the Abbey of Psalmodiet to exploit this valuable commodity in the Peccais Ponds. The salt has long been one of the main resources of the city. To achieve "table salt quality", water pumped from the sea travels more than 70 km in "roubines". The concentration of sodium chloride is from 29 to more than 260 g/kilo. Mechanically harvested salt is piled up in the twinkling "camelles" before being packaged. It is suitable for human consumption.

Tourism[]

The medieval heritage from the 13th and 14th centuries of the commune and its proximity to the sea attract many tourists and residents of France.

Transport[]

River[]

The city of Aigues-Mortes is a crossroads of canals:

- Canal du Rhône à Sète from the north-east and leaving westward

- Canal de Bourgidou to the southeast, and joins the Petit Rhône via other channels to the limit of Gard and Bouches-du-Rhône

- Le Grau-du-Roi, maintained since the Middle Ages and connecting Aigues-Mortes to the central part of Grau-du-Roi

Railway[]

The Line Nîmes to Le Grau-du-Roi serves the towns and villages of Costières and the coastline, with a terminus at Le Grau-du-Roi. It is also used for the transport of salt produced by the saltworks of the Salins Group (see link below).

Road[]

The development of seaside tourism since the 1960s was marked by the construction of new resorts (La Grande-Motte) and the extension of existing facilities from Le Grau du Roi to Port-Camargue. To facilitate access to tourists, a coastal road network has been augmented and connected to the A9 motorway. Aigues-Mortes benefits in these ways:

- to the east, the road D58 connects the city to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and the commune of Arles. This road winds through the rice fields and the various ponds that make up the Camargue.

- to the west, the road D62 was enlarged for cars to make a quick connection to Montpellier

- to the north, the road D979 directly connects the town to the motorway at Gallargues-le-Montueux

The bus 106 also connects Montpellier and Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

Administration[]

Municipal Administration[]

The municipal council consists of 29 members including the mayor, 8 deputies, and 20 municipal councilors.

Since the last municipal elections, its composition is as follows:

| Group | President | Effective | Statut | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Aigues-Mortes differently" PS |

Cédric Bonato | 20 | majority | ||

| "Act for Aigues-Mortes" UMP |

Pierre Mauméjean | 5 | opposition | ||

| "I Love Aigues-Mortes" DVD |

Didier Charpentier | 3 | opposition | ||

| Independent EELV |

Didier Caire | 1 | opposition |

List of Successive Mayors of Aigues-Mortes[32]

- Mayors from 1944

| From | To | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | 1953 | Éric Hubidos | |

| 1953 | 1959 | Alexandre Molinier | PCF |

| 1959 | 1965 | André Fabre | PCF |

| 1965 | 1977 | Maurice Fontaine | RI |

| 1977 | 1989 | Sodol Colombini | PCF |

| 1989 | 2008 | René Jeannot | UDF then DVD |

| 2008 | 2014 | Cédric Bonato | PS |

| 2014 | 2026 | Pierre Mauméjean | UMP |

Canton[]

The town is the capital of the canton of the same name whose general councillor is Leopold Rosso, deputy mayor of Le Grau-du-Roi and president of the Community of Communes Terre de Camargue (UMP). The canton is part of the arrondissement of Nîmes and the second electoral district of Gard where the member is Gilbert Collard (FN ).

Population[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 7,115 | — |

| 2007 | 7,613 | +7.0% |

| 2008 | 7,891 | +3.7% |

| 2009 | 8,116 | +2.9% |

| 2010 | 8,341 | +2.8% |

| 2011 | 8,543 | +2.4% |

| 2012 | 8,565 | +0.3% |

| 2013 | 8,450 | −1.3% |

| 2014 | 8,417 | −0.4% |

| 2015 | 8,385 | −0.4% |

| 2016 | 8,316 | −0.8% |

Distribution of age groups[]

The distribution of the population of the municipality by age group is as follows:

- 47.6% of men (0–14 years = 17.7%, 15–29 years = 17.1%, 30–44 years = 22%, 45 to 59 years = 21.1% over 60 years = 22%)

- 52.4% of women (0–19 years = 16.9%, 15–29 years = 15.1%, 30–44 years = 23.5%, 45–59 years = 19.9%, more than 60 years = 24.5%)

The female population is over-represented compared to men. The rate of (52.4%) is substantially the same as the national rate (51.8%).

Percentage Distribution of Age Groups in Aigues-Mortes and Gard Department in 2007

| Aigues-Mortes | Aigues-Mortes | Gard | Gard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 0 to 14 Years | 17.7 | 16.9 | 19.1 | 17.0 |

| 15 to 29 Years | 17.1 | 15.1 | 17.7 | 16.1 |

| 30 to 44 Years | 22.0 | 23.5 | 19.9 | 19.8 |

| 45 to 59 Years | 21.1 | 19.9 | 21.3 | 20.9 |

| 60 to 74 Years | 15.7 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 15.1 |

| 75 to 89 Years | 6.0 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 9.9 |

| 90 Years+ | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

Local Culture[]

The Aigues-Mortes Fougasse[]

Fougasse was one of the first pastries which could rise. It can be sweet (sometimes called "tarte au sucre" or sugar tart) or salty (with or without gratillons).

Traditionally, making sweet fougasse in Aigues-Mortes was reserved for the Christmas period, as part of the Thirteen desserts. Based on a brioche dough, sugar, butter, and orange blossom, it was made by the baker with ingredients provided by the client. Now Aigues-Mortes fougasse sells all year.

Lou Drapé[]

Lou Drapé is an imaginary horse mentioned in local folklore, which was supposed to walk at night around the ramparts of the city and take 50 to 100 children on his back, and disappear to "nowhere".[33]

Historical sites[]

Aigues-Mortes has a very large number of sites registered as historical monuments[34] and historical objects.[35]

The Tower of Constance and the ramparts[]

The was built in 1242 by Saint-Louis on the former site of the Matafère Tower which was built by Charlemagne around 790AD to house the king's garrison. The construction was completed in 1254.

It is 22 metres in diameter with a height of either 33 or 40 metres depending on the source. The thickness of the walls at the base is 6 metres.

On the ground floor, there is a guardroom protected by a portcullis. In the middle of the room, there is a circular opening leading to the cellar which served as a pantry, storage of ammunition as well as for dungeons. These areas were called the "culs de basse fosse", an old way of saying underground dungeons in French.

On the first floor, there is the knight's hall. Structurally it is similar to the guardroom. It was in this room that the Protestants were imprisoned during the 18th century, most notably Marie Durand, who engraved the word "résister" (English: resist) into the edge of the well which can be seen to this day. She was imprisoned at the age of 15, and was freed 38 years later, along with political prisoners such as Abraham Mazel, leader of the Camisards.

Between these two rooms, a narrow, covered way was built within the walls to keep watch on the room below.

After the knight's hall, there is an entrance to the terrace which offers a wide panoramic view of the region, making it an ideal position for surveillance. Sometimes, the prisoners were allowed to go on the terrace to get some fresh air.

The ramparts stretch for a distance of 1650 metres. Spectacular in their height and their state of preservation even though they were not restored in the 19th century, as was Carcassonne for example, they remain in a well preserved state. Along with the Tower of Constance, they are a testimony to Western European military architecture in the marshlands during the 13th and 14th centuries.

City walls 1

City walls 2

City walls 3

City walls 4

City wall 5

City wall 6

City wall 7

City wall 8

The entrance of the Queen, Aigues-Morte in 1867, by Frédéric Bazille, displayed at Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Carbonnière Tower[]

Located in the commune of Saint-Laurent-d'Aigouze, the Carbonnière Tower was first referred to in an old text from 1346 specifying the function of the structure. It said, "this fortress is the key to the kingdom in this region." Surrounded by salt marshes, the fortress was the only passageway into Aigues-Mortes. It was guarded by a garrison made up of a châtelain and several guards. From the terrace, which could support up to four cannons, there is a panoramic view of Petite Camargue.

Aerial view of the Carbonnière Tower

The Church of Notre-Dame-des-Sablons[]

The is a Gothic-style church and was probably built before the ramparts in the mid-13th century during the time of Saint-Louis. In 1537 it served as a Collegiate church but was later vandalized by Protestants in 1575. After the reconstruction of the bell tower in 1634 it later served as a Temple of Reason during the French Revolution, a barracks, grain merchant, and a salt warehouse. It was re-established as a place of worship in 1804 and the building was restored in the neo classical-baroque style. Between 1964 and 1967 all of the 19th century decor was removed, notably the coffered ceilings, resulting in the much more basic and medieval style church we see today. Since 1991, the stained-glass windows by Claude Viallat, a contemporary artist belonging to the "Supports/Surfaces" art movement, add extraordinary light and colour to the building. With the exception of a few statues, the rest of the 18th and 19th century furniture disappeared during this period. The façade is crowned by a simple bell-gable housing 3 bells. The largest of the three is 1.07 metres in diameter. It was dated to 1740, cast by master smelter Jean Poutingon, and has been designated a historical monument of France. The church also houses a statue of Saint-Louis.

Church of Notre-Dame-des-Sablons

Statue of Saint-Louis in the Church of Notre-Dame-des-Sablons

Remains of a crucifix in the Church of Notre-Dame-des-Sablons

The Chapel of the Gray Penitents[]

The is located to the east of the Place de la Viguerie. It is the property of the Brotherhood of Grey Penitents established in 1400. The facade is in the style of Louis XIV. The entrance door is from the 17th century and is decorated with a wooden statue. The altarpiece was carved in 1687 by Sabatier.

Inside, an altarpiece represents the passion of Christ. It was built of gray stucco plaster in 1687 by the sculptor Sabatier from Montpellier. This altar, on which are the arms of the brotherhood, occupies the back of the choir.

The Chapel of the White Penitents[]

The is located at the corner of the Rue de la République and Rue Louis Blanc. It belongs to the Brotherhood of the White Penitents which was created in 1622.

Above the choir, on the roof, there is a copy of the Retable of Jerusalem where Christ celebrated the Passover and Holy Thursday with his apostles. Around the high altar, a painting on canvas traces the descent of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost. It is attributed to Xavier Sigalon a painter born in Uzès in 1778 . On each side of the choir stand two statues: on the left Saint Felix for the redemption of captives, on the right James, son of Alphaeus, first Bishop of Jerusalem.

Saint-Louis Square[]

This is the touristic heart of the city. In the centre, opposite the main entrance of the Porte de la Gardette, stands the statue of Saint-Louis, the work of James Pradier in 1849.

Plan des Theatres[]

The [36] are arenas for the Camargue bullfights. They were listed in 1993 on the inventory of the list of Historic Monuments (MH)[37] for their ethnological and cultural interest. They can accommodate more than 600 people.[38]

Aerial Views[]

Aigues-Mortes

Aigues-Mortes

In popular culture[]

Literary references[]

- Ernest Hemingway's third major posthumous work, the novel The Garden of Eden, takes place in Aigues-Mortes.

- Wayne Koestenbaum set his 2004 novel Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes in Aigues Mortes.

- Michael Moorcock's Hawkmoon novels feature Aigues Mortes as the site of Castle Brass and capital city of a futuristic "Kamarg".

- Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron, Second Day, Seventh Story, as the place the king's daughter was shipwrecked in her false explanation of her four-year absence.

Architectural references[]

- The unique layout of the University of California, Santa Cruz was directly inspired by the layout of Aigues-Mortes, according to UC President Clark Kerr.[39]

Notable people linked to the commune[]

- Emmanuel Theaulon, playwright, born in Aigues-Mortes on 14 August 1787.

- Michel Mézy, former footballer, born in Aigues-Mortes on 15 August 1948.

- Frédéric Bazille, one of the founders of Impressionism, represented Aigues-Mortes in one of his paintings.

- Maurice Fontaine, former senator and mayor.

Gallery[]

|

See also[]

- Communes of the Gard department

- List of works by James Pradier Statue of Saint Louis

- Principality of Aigues-Mortes

References[]

- ^ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires". data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises (in French). 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Populations légales 2018". INSEE. 28 December 2020.

- ^ Watersteps through France - Bill & Laurel Cooper - Adlard Coles Nautical - 1991 - ISBN 9780749310165

- ^ A Spell in Wild France - Bill & Laurel Cooper - Methuen - 1992 - ISBN 9780413667205

- ^ Inhabitants of Gard (in French)

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, The massacre of the Italians of Aigues-Mortes, Fayard, 2010, p. 13 (in French)

- ^ History of research in the commune of Aigues-Mortes (in French)

- ^ "Aigues-mortes, The salt of Life". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 18

- ^ Order of Guillaume de Roussillon in 1275 - (Roger, La noblesse de France aux croisades, [Édition ? Date ?] p. 158; C. Rollat, The case of Guillaume de Roussillon in the Templar Tragedy of Pilat at Aigues Mortes) 1274–1312 (in French)

- ^ Michel Melot, Guide to the Mysterious Sea, Éd. Tchou et Éditions Maritimes et d'Outre-Mer, Paris, 1970, p. 714. (in French)

- ^ Letters Patent from Louis XI, Tours, 5 June 1470 (in French)

- ^ BN L. K7 50

- ^ Aigues-Mortes on the Dimeli and Co website (in French)

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Aigues-Mortes, EHESS. (in French)

- ^ Report cited by Antoine César Becquerel in 1865 in: Becquerel (Antoine César, M.), Memoire on the Forests and the Climatic influence (Numbered by Google), 1865, see page 54.

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 33–43

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, The Massacre of the Italians at Aigues-Mortes, Fayard, 2010, p. 51 (in French)

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 53 (in French)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gérard Noiriel The Massacre of the Italians, Fayard 2010, p. 55

- ^ Gérard Noiriel The Massacre of the Italians Fayard 2010, p. 56

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 58

- ^ An eighth victim died of Tetanus a month later

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 58–63 (in French)

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 121

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 134–136

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 139

- ^ , the Italian workers on one side, France for the riots in front of the Palazzo Farnese - the French Embassy in Rome.

- ^ Gérard Noiriel, op. cit., p. 149

- ^ Jump up to: a b Google Maps

- ^ See "Sable-de-camargue" in the French Wikipedia (in French)

- ^ List of Mayors of France

- ^ See "Drapé (légende)" in the French Wikipedia

- ^ Base Mérimée: Search for heritage in the commune, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Base Palissy: Search for heritage in the commune, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ See "Plan des Théâtres (Aigues-Mortes)" in the French Wikipedia (in French)

- ^ see the page on Historical Monuments (in French)

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Maudet, Terres de taureaux - Les jeux taurins de l'Europe à l'Amérique, Madrid, Casa de Velasquez, 2010, 512 p. (ISBN 978-84-96820-37-1), p. Annexe 112 pages p. 84 (in French)

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

Bibliography[]

- Frédéric Simien, Aigues-Mortes, éditions Alan Sutton, 2006. ISBN 2-84910-389-6

- Frédéric Simien, Aigues-Mortes, tome II, éditions Alan Sutton, 2007. ISBN 978-2-84910-561-0

- Frédéric Simien, Aigues-Mortes, tome III, éditions Alan Sutton, 2011. ISBN 978-2-8138-0345-0

- Frédéric Simien, Camargue, fille du Rhône et de la mer, éditions Alan Sutton, 2010.

- Sur les événements de 1893, Enzo Barnabà, Le sang des marais, Marseille, 1993

- Gérard Noiriel, Le massacre des Italiens d'Aigues-Mortes, Fayard, 2010 ISBN 978-2-213-63685-6

- Christian Rollat, L'Affaire Roussillon dans la Tragédie Templière , Rollat 2006. ISBN 978-2-9527049-0-8

- Luc Martin, L'été de la Colère - la tragédie d'Aigues-Mortes - Août 1893 [éditions Grau-Mots 2012] ISBN 978-2-919155-08-8

- Pierre Racine, Mission impossible ? L'aménagement touristique du littoral du Languedoc-Roussillon, éditions Midi-Libre, collection Témoignages, Montpellier, 1980, 293 p.

External links[]

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aigues-Mortes. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aigues-Mortes. |

- Geomorphology of the Rhone Delta, Richard Joel Russell, 1942, ANNAL, Association of American Geographers, volume 32, issue 2, pages 149–255

- Office of Tourism of Aigues-Mortes

- Aigues-Mortes guide Navigation and mooring information.

- Aigues-Mortes Photogallery (in French)

- Photos of Aigues Mortes (in French)

- Aigues-Mortes on Lion1906

- Aigues-Mortes on Géoportail, National Geographic Institute (IGN) website (in French)

- Aiguesmortes on the 1750 Cassini Map

- Aigues-Mortes, John Reps Bastides Collection, Cornell University Library

- Tower of Constance on Base Mérimée

- Church of Notre-Dame-des-Sablons on Base Mérimée

- Chapel of the Gray Penitents on Base Mérimée

- Chapel of the White Penitents on Base Mérimée

- Plan des Theatres on Base Mérimée

- Crusade places

- Communes of Gard

- Monuments of the Centre des monuments nationaux