Bayswater, Western Australia

| Bayswater Perth, Western Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View of King William Street south from the Bayswater Subway in October 2020 | |||||||||||||||

Bayswater Location in metropolitan Perth | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 31°55′03″S 115°54′49″E / 31.91750°S 115.91361°ECoordinates: 31°55′03″S 115°54′49″E / 31.91750°S 115.91361°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 14,432 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,468.2/km2 (3,802.5/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1885 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 6053 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 9.83 km2 (3.8 sq mi)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 6 km (4 mi) from Perth | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Bayswater | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Maylands, Bassendean | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Perth | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Bayswater is a suburb 6 km (4 mi) north-east of the central business district (CBD) of Perth, the capital of Western Australia. It is just north of the Swan River, within the City of Bayswater local government area. It is predominantly a low-density residential suburb consisting of single-family detached homes. However, there are several clusters of commercial buildings, most notably in the suburb's town centre, around the intersection of Whatley Crescent and King William Street and a light industrial area in the suburb's east.

Prior to European settlement, the Mooro group of the Whadjuk Noongar people inhabited the area. In 1830, the year after the European settlement of the Swan River Colony, land along the river was divided between the colonists, who moved in soon after. Most either died or left in the months following, leaving the area undeveloped for most of the 19th century. In 1881, the Fremantle–Guildford railway line was built, triggering the founding of the Bayswater Estate, the first development in the area, and in 1897, the Bayswater Road Board was founded, giving Bayswater its own local government. At first, development consisted of nurseries, market gardens and dairies, but as time went on, Bayswater became more and more suburban. Today, Bayswater is fully suburbanised, with the subdividing of older lots being commonplace. Plans for apartments around Bayswater and Meltham railway stations are a contentious issue.

Parks and wetlands, including the , the Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary and . There are other parks throughout the suburb, including Bert Wright Park, (which includes a war memorial), Hillcrest Reserve and Houghton Park line Bayswater's Swan River foreshore. Major roads through the suburb include Guildford Road, which connects to the Perth CBD and Tonkin Highway.

History[]

Before European colonisation[]

Prior to European settlement, the area was inhabited by the Mooro group of the Whadjuk Noongar people. They were led by Yellagonga and inhabited the area north of the Swan River, as far east as Ellen Brook and north to Moore River. The Swan River provided fresh water and food, as well as being a place for trade. A camping ground, at least 4,500 years old, existed just north of the present-day junction of Tonkin Highway and Guildford Road. Another camping ground likely existed in the area now known as the .[3][4][5]: 1–6

European colonisation[]

When Europeans founded the Swan River Colony in 1829, they did not recognise the indigenous ownership of the land. John Septimus Roe, the colony's Surveyor General, surveyed the land along the Swan River. His survey resulted in the land being divided into long, narrow rectangular strips extending from the river. As the river was the only method of transportation in the colony's early years, each piece of land had to have river frontage. The long, narrow strips were called "ribbon grants". In 1830, the colonists travelled up the river to the land allotted to them. That year, the Swan River flooded several times, washing away crops and inundating shelters. The colonists were unlucky, as floods were not an annual occurrence. Most of these colonists either died or left the area soon after.[4][5]: 8–17

After it was abandoned, several other people bought the land, including Peter Broun (Location S) and William Henry Drake (Location U). With numerous other land holdings around the colony, however, they never lived on or improved the land. The last colonists, the Drummond family, left the area in 1836.[4][6][5]: 18, 20 By 1833, a track was cleared connecting Perth to Guildford. The track was useable by carriages, but the sandy soil made it difficult. When The Causeway opened in 1836, a route south of the river became the main route from Perth to Guildford, making the track north of the river a minor route. Because of this, the track deteriorated to the point that some people "refused to allow their horses to go for hire on this track". That track is a precursor to what is now Guildford Road.[4][5]: 21

Between 1830 and 1880, only two houses are known to have been built in the area: one owned by Frederick Sherwood, the other by John Scrivener. Neither house is still standing.[5]: 24–26 The oldest remaining piece of physical evidence of European settlement in the area is an olive tree on Slade Street, supposedly planted in the 1840s and used as a place for religious services. That olive tree is now represented on the City of Bayswater's logo.[7] A mulberry tree cut down in the 1970s had 130 growth rings.[5]: 22

Initial development in the 1880s[]

In 1881, the Fremantle–Guildford railway line was built. There were many arguments over whether it should be laid north or south of the river. The northern option was the one eventually chosen. What was previously a several hours-long trip to get from what is now Bayswater to Perth or Guildford took twenty minutes by train. There was now opportunity to develop the isolated and underused land grants.[5]: 30–31 Patronage on the line exceeded everyone's expectations. Many racegoers got off the line at the part closest to the Perth Race Course, hiked through the bush to the river, where men with boats were waiting to ferry people across the river to the race course. In c. 1885, a footbridge was built across the river, near what is now the Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary, to serve racegoers.[5]: 31

In June 1885, increased interest in Perth's real estate market began, labelled a "land boom". William Henry Drake, the owner of Location U, died in Bayswater, London, in 1884. Stephen Henry Parker, using his power of attorney for Drake, placed Location U on the property market. The advertisement for the land did little to recommend it, making no mention of the railway line or the possibilities for subdivision. Joseph Rogers, a property developer from New South Wales who saw the land's potential, unlike the locals who saw it as a backwater, bought the land.[5]: 32 In July 1885, Rogers, along with his associate Feinberg, placed the land, now named the Bayswater Estate, on the property market again, this time subdivided into 5-acre (2 ha) lots. Whether the name had any connection to Drake is unknown. It was common practice for property developers to pick a pompous name for an estate at random. Either way, the suburb of Bayswater is named after the Bayswater Estate. A road was surveyed running down the middle of the estate, named Coode Street north of the railway line and King William Street south of the railway line. In the 9 July 1885 edition of The Daily News, an advertisement appeared for the Bayswater Estate that was probably the largest ever real estate advertisement to run in any Western Australian newspaper at the time. The advertisement spanned the entire height of the page and covered over a quarter of its width.[5]: 33–34

People began buying the land. One person who purchased a lot was Thomas Molloy, a City of Perth councillor and land investor. He had been led to believe his land was close to the railway, but it was actually on the northern end of the Bayswater Estate, far from the present City of Bayswater and closer to Wanneroo than the railway. When he discovered this, he made his annoyance clear to Winthrop Hackett, the editor of The West Australian. On the day of the second auction, Hackett printed an attack on the auctioneers and the Bayswater Estate land in the newspaper. The second and third auctions were poorly attended. As a result, Rogers and Feinberg sued The West Australian for defamation, alleging it had caused them a financial loss because of the poorly attended auctions. They won the case, being awarded damages of one farthing, however they were never paid.[5]: 33–34

The decision to subdivide the land into 5-acre (2 ha) lots rather than smaller lots typical in a town meant the estate remained rural. Landowners made use of the land for nurseries, dairies and other agricultural activities. As there was no supervision of building standards, houses were constructed out of corrugated iron and weatherboard, built by the landowners themselves. By January 1886, a branch line was built through Location T over to the river near the Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary's current location.[8] The intention was for it to be part of a railway to Busselton, however this never happened. A footbridge was built later that year, so people no longer had to be ferried across the river.[5]: 35–37

During the late 1880s, Locations V, W and X changed hands several times. Locations X and W were eventually subdivided. Many of the lots were sold to speculators from Victoria and New South Wales, but a few buyers actually lived on their lots. Unlike the other locations, Location V was not subdivided. The only other ribbon grant in the district was Location T, which remained with the original owner's family. However, part of Location T was leased to Henry Walkenden, who established a brickworks there in 1887. This was the first industrial site in Bayswater. It employed up to 18 men, some of whom camped on the surrounding land. The railway was likely used to transport the bricks. Remnants of the site, like Gobba Lake, which was a clay pit, still exist to this day.[5]: 37–38 [9][10]

New services in the 1890s[]

The first attempt to get a school for Bayswater occurred in 1889, however, the campaign for that was quickly knocked back by the state Board of Education. A second, more thought-out campaign occurred in 1892. Residents managed to convince the Board of Education to take a tour of the area. Afterwards, the Board decided Bayswater deserved a school. A site was purchased, and a one room weatherboard building was constructed. Named Bayswater State School, with 29 pupils when it opened in 1894, its size was insufficient.[5]: 41–42 In the years that followed, the head teacher wrote several letters to the Education Department about overcrowding. By 1896, there were about 12 pupils who had to stand in the aisles, with the head teacher forecasting overcrowding would only worsen.[5]: 50 The first upgrade occurred in 1900.[4]

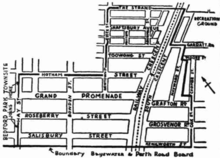

Another matter of importance for residents in the 1890s was for Bayswater to get its own road board. Bayswater was a small settlement, awkwardly straddling the boundaries of the Perth and Swan Road Districts. In December 1894, residents held a meeting to petition for a road board. The government rejected the petition. A second attempt to get Bayswater's own road board in 1896 was successful. Both the Perth and Swan Road Boards were happy to relinquish responsibility for building roads there. The Bayswater Road Board was gazetted on 5 March 1897, becoming one of several new local government areas established in the 1890s along the railway. A wooden ratepayers' hall was constructed on Guildford Road.[4][5]: 42, 50

Bayswater gained many other services in the 1890s. A post office was established on King William Street in 1895. The railway was duplicated. Shortly thereafter, in 1896, the Bayswater railway station was constructed. The railway became a major employer in Bayswater, with the station needing many staff for passenger services and the goods yard. Some made the commute to Perth by train daily. After lobbying by the Western Australian Turf Club, the branch line was extended across the river to the Perth Race Course in 1897. Baptist, Anglican, Methodist and Catholic churches were established, Bayswater's Baptist church being the first one in Western Australia.[5]: 37–50

Further subdivision of the 5-acre (2 ha) lots at Location U occurred between 1895 and 1899. Roads were surveyed in a grid pattern instead of following the terrain. Steep hills would make it a challenge for the roads board to construct them and for horse-drawn vehicles to traverse them afterwards. Location W was subdivided further, effectively creating two settlements in Bayswater.[5]: 52 Despite these subdivisions, Bayswater was not densely populated. Because the land was cheap, many people bought several adjoining lots for a garden. Houses were still shoddily built, and most are no longer standing.[5]: 53 Dairies, slaughterhouses and market gardens were interspersed between the houses, and more brickyards and an ironworks were established in the eastern part of Bayswater. In 1897, the population of Bayswater was estimated to be 400. At the end of the decade, Bayswater was no longer an isolated and poorly serviced district.[4][5]: 50–52

After Federation[]

After the Federation of Australia in 1901, there were tensions between the agricultural and residential elements of Bayswater. William Williams, a member of the road board, complained about cattle being a nuisance. Dairyman and fellow board member Edward Browne fought back, saying "cattle had been the making of the place". The piggeries received many more complaints, however, with concerns about their odour and noise from the pigs being killed on site. In 1903, the Bayswater Local Board of Health, controlled by the same members as the road board, disallowed piggeries from being situated between the river and 1 mi (1.6 km) north of the railway line.[5]: 51 Another thing the road board began regulating in 1903 was subdivisions. Small blocks and close together streets were among the things that the road board put an end to.[5]: 53

The opening of the Midland Railway Workshops down the railway line in 1904 fuelled much growth, with workers migrating from the eastern states and overseas, particularly Britain. By 1908, many residents of Bayswater were from Victoria. Of thirty-three births in 1908, nineteen fathers and eighteen mothers were from Victoria.[5]: 56 Most of the structures built after 1904 were made of bricks and weatherboard, and those made of corrugated metal were no longer makeshift buildings. These buildings were designed to be more permanent, and many still stand today.[4][5]: 58 The West Australian noted in March 1909 that "the days of the 'humpy' (temporary shelter) have passed away" and "Very few houses in the town are now without a metalled road to connect them with the railway station".[11]

A group of commercial buildings formed along King William Street in the 1900s, some of which were actually designed by an architect. In 1904, Gold Estates of Australia Pty Ltd, a gold prospecting company that had branched out to real estate, acquired Location V, the sole remaining intact ribbon grant. The company subdivided the land, marketing it as the "Oakleigh Estate".[5]: 59 This estate bridged the gap between the two developed areas of Bayswater, making it into one contiguous settlement. By 1909, the population boom had ended, leaving the population of Bayswater to rise steadily after that.[5]: 60 In 1909, the King William Street subway was constructed. Prior to that, people had to use either the footbridge at Bayswater station or cross the railway at grade. Soon enough, there were complaints about herds of cattle going through it in the morning.[4][5]: 66 The 1911 census recorded the population of Bayswater was 1,758.[12] The outbreak of World War I brought British migration to a standstill. Bayswater stagnated and land values plummeted. People who tried to sell their land failed and had to take it off the market. Part of the problem in selling was because the water table was rising across Perth, areas that were once useable became inundated with water. Tram services were built to Victoria Park and Nedlands, but not Bayswater, despite a campaign by the Oakleigh Park Progress Association.[5]: 67–69 After the war, however, Bayswater's commercial centre expanded.[5]: 70–71 In 1921, the population of Bayswater was 2,365.[13]

In the middle to late 1920s, the Roads Board began to put more care into Bayswater's amenities. One initiative they undertook was to acquire a market garden in the suburb's town centre to be converted to a park. It was considered undesirable for a market garden to be on the main street of Bayswater, and so the land was turned into Whatley Gardens. It would later be named Bert Wright Park.[4][9] Several modern industrial complexes were built in the middle to late 1920s. These included a foundry in 1927 and a large Cresco fertiliser factory, which led to numerous complaints about air pollution.[5]: 74 This was a catalyst for the district's first town planning scheme, which reinforced locating industry in the eastern part of Bayswater and kept it out of the western part. There were several teething problems, with people unaccustomed to restrictions on where they could set up businesses, and several petitions and appeals to the town planning scheme resulted.[5]: 174 This was one of the first town planning schemes in Western Australia, and it preceded the Stephenson–Hepburn Report by 22 years.[4]

During the 1930s, dairies around Bayswater slowly started to disappear. The Whole Milk Act of 1933 made setting up new dairies substantially difficult. The established dairies were a source of numerous complaints about noise, dust and the traffic caused by them, among other things.[5]: 177 In 1934, a railway station between Bayswater and Maylands was first suggested. The first Garratt Road Bridge was built across the Swan River in 1934, linking Bayswater and Ascot. It opened on 1 January 1935.[4][5]: 173 In the late 1930s, the townsites of Bayswater and Meltham Heights were gazetted, Meltham Heights consisting of the area around Hotham Street.[14] Transport for Meltham Heights was an issue. With the area being working class, car ownership was uncommon. People agitated for a railway station at Meltham, however, that was a while off.[5]: 179 [15][16]

From April 1942 to the middle of 1943, Bayswater became the centre of army signalling operations in Perth. They were stationed there in anticipation of a Japanese invasion of Western Australia. Many homes and buildings were taken over for the purposes of signalling. The town hall was used by the military, and the road board had to pack its operations into the small parts of the building that were available. A large aerial was put up at the present-day site of Hillcrest Primary School. New factories were constructed and existing factories were converted to supplying military equipment. The federal government constructed a factory in between Garratt Road and Milne Street, in the middle of a residential area instead of the large industrial area just to the east, irritating residents and the road board.[5]: 199–201

Post World War II[]

Bayswater and its surrounding suburbs' population surged following the end of World War II. Housing construction, which was non-existent during the war, proceeded at a rapid rate post-war.[5]: 207 Development occurred in Meltham Heights, and construction of Meltham station finally began in 1947. Shortages of labour and materials prevented the station's completion until 1949.[5]: 179 [15][16] A police station opened in Bayswater in 1954.[5]: 234 The Belmont spur line closed in 1956 after fire damaged the bridge crossing the Swan River.[4]

Because of the considerable growth, a new primary school was necessary. The Department of Education foresaw a large protest if a new school was not open by 1950. A site atop a hill on Coode Street was selected in March 1949, however its steep nature delayed construction. With an urgent need for the new school to open, three classrooms were transported from East Fremantle to the site. The school opened in 1950 to 120 pupils and criticisms of its basic facilities. The school's buildings were expanded over the course of the decade, and in 1958, its population was approximately 700.[5]: 219–221 The population of Bayswater Primary School was also burgeoning, with 700 students in 1954. Its facilities were far too small, but the Department of Education did little about it. In August 1957, the school caught fire, destroying the original 1894 building, as well as several classrooms and the administration section. This forced the government to construct new and better facilities.[5]: 221

A proposal by the railway department for the East Perth railway marshalling yards to be relocated to Bayswater attracted protesters. They pointed out that the Midland line would be electrified eventually and Bayswater would be on the outskirts of Perth. The railway department ignored the protesters, resuming the land of 33 houses. The 1955 Stephenson–Hepburn report recommended the marshalling yards be built in the Kewdale–Belmont area instead, ending the plan for marshalling yards in Bayswater.[5]: 236 [17] The Stephenson–Hepburn report also had a negative impact on Bayswater, proposing that two highways be built through the suburb. One would run along the river, named Swan River Drive, and the other from north to south, named the Beechboro-Gosnells Highway.[17] The Metropolitan Region Scheme, adopted in 1963, accepted most of the recommendations of the Stephenson–Hepburn report, including the two proposed highways. The scheme had zoned large chunks of land through Bayswater as reserves for controlled access highways.[18] Those who owned land zoned for the highways could not build on it, causing much frustration. Swan River Drive was particularly controversial, as its route followed the Swan River foreshore.[5]: 243

Starting in 1961, the Swan River foreshore in Bayswater was used as a landfill. Unusable for much else because of seasonal flooding and wetlands not being valued, the aim was to fill in any low-lying parts along the river and cover the area in grass to create a reserve. The Shires of Bassendean, Bayswater and Perth made use of the landfill for 17 years.[5]: 251 [19] Between the 1960s and 1980s, the names for the communities of Meltham, Oakleigh Park and Whatley disappeared as these suburbs were absorbed into Bayswater. This began in 1967, when they were allocated the same postcodes as Bayswater. Whatley, in particular, put up an unsuccessful fight to retain its identity.[5]: 269

In 1971–72, the second Garratt Road Bridge was built parallel to the 1934 bridge, resulting in two lanes in each direction across the river. The newer bridge was the last wooden bridge constructed in Perth, and both are now heritage listed.[4] In 1973, the shire opened Mertome Village, the first aged care complex to be built by a local government in Australia.[5]: 280 The name is a shortening of Merv Toms, who was chairman of the road board in the 1950s, and a local member of parliament who played a significant role in managing the Mertome Village project. The village signifies the changing role of local government in Australia, from building roads to providing social services.[5]: 280 [20] Around the early 1970s, Bayswater was almost developed to its current extent. The last areas to be developed being the residential area in the suburb's north-east.[5]: 284 Coming into the late 1970s, it was realised that having a waste landfill by the river was an environmental hazard, and so the landfill was closed in 1980. A waste transfer station was established on Collier Road, and a new landfill was established at Red Hill.[5]: 283, 291

In the 1980s, the plans for Swan River Drive were scrapped, much to the relief of residents. The Beechboro-Gosnells Highway went ahead, however, the first section between Railway Parade and Morley Drive in Morley opening in 1984. Its name upon opening was Tonkin Highway. Various roads, including Beechboro Road, were split apart by the highway.[21]: 311 [22] Tonkin Highway was extended southwards to connect over the river in 1988, creating a new interchange at Guildford Road and fully severing the two sides of Bayswater.[21]: 312 The highway relieved heavy congestion through Bayswater, particularly at the Bayswater Subway and Garratt Road Bridge.[5]: 291

21st century[]

As of the 2010s and 2020s, development in the Bayswater town centre and around Meltham station is a contentious issue. The City of Bayswater started work on a structure plan for the Bayswater town centre in November 2015.[23] The structure plan would cover building heights, land uses and connections for cars, pedestrians and cyclists.[24] A draft of the structure plan was released in July 2017,[25] and public comments on it were invited in August 2017.[26]

In June 2019, (previously the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority) began the process of expanding the Midland Redevelopment Area to include the areas around Bayswater station and High Wycombe station, renaming it the Metronet East Redevelopment Area.[27] DevelopmentWA said the purpose of the redevelopment area was to "maximise development opportunities arising from the station upgrades and help create a well-designed and connected community hub." Its purpose would be to take development planning control away from the local government and the Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC), and give it to DevelopmentWA.[28] The boundaries of the area were formally established in May 2020.[29][30] A draft redevelopment scheme for Metronet East was released in August 2020.[31] The redevelopment scheme was formally adopted in May 2021, transferring planning authority from the City of Bayswater and the WAPC to DevelopmentWA.[32][33] The redevelopment scheme provides the legal process for applying for development in the redevelopment area.[34]

In July 2021, draft design guidelines for the Bayswater section of the Metronet East Redevelopment Area were released to public comment.[35] The design guidelines are intended to guide the redevelopment of land within the redevelopment area, including guides for building heights, setbacks, and provision of car parking spaces. The draft guidelines allow for buildings as tall as 15 stories in the central part of the town centre. The development scheme allows for buildings to break the design guidelines if DevelopmentWA approves the development application for that building.[36]

In 2019 and 2020, the City of Bayswater proposed to turn part of eastern Bayswater into a new suburb called Meltham, reminiscent of the old townsite of Meltham Heights. The new suburb would have centred on Meltham station within an area of 107 ha (260 acres). Responses from the residents indicated that 54% were opposed to the renaming for various reasons, including criticism of the name, worries that property values would decrease and the association of Meltham with anti-social behaviour. City of Bayswater councillors decided in May 2020 not to proceed with the new suburb.[15][37][38]

In February 2020, City of Bayswater councillors voted to heritage protect the entire town centre. This resulted in a backlash from some residents and the community group Future Bayswater, who say that it may hamper development and protect buildings with little-to-no heritage value. However, other residents and the community group Bayswater Deserves Better praised the move to heritage protection.[39] The structure plan was finalised in June 2020.[40][41]

Geography[]

Bayswater is located 6 km (4 mi) north-east of the central business district (CBD) of Perth, the capital of Western Australia, 15 km (9 mi) east of the Indian Ocean, and covers an area of 9.83 km2 (3.80 sq mi). The elevation ranges from 2 m (7 ft) on the banks of the Swan River to 45 m (148 ft) at Hillcrest Primary School. The suburb is bounded on the south by the Swan River, with Ascot on the opposite side of the river, bounded to the west by Maylands, to the north by Bedford, Embleton and Morley, and to the east by Bassendean and Ashfield, which are in the Town of Bassendean. Bayswater also shares corners with Inglewood and Eden Hill.[42]

Bayswater consists predominantly of low-density single-family detached homes, zoned as "urban" in the Metropolitan Region Scheme. There is an industrial area in the eastern parts of the suburb and a small town centre around King William Street and Whatley Crescent.[43] The Tonkin Highway and the Midland railway line divide the suburb.

The streets throughout the suburb mostly follow a grid pattern. The roads perpendicular to the Swan River are remnants from the rectangular ribbon grants which extended from the river; the roads roughly parallel to the river are remnants of the later subdivision of Bayswater into 5-acre (2.0 ha) lots. Streets named after Bayswater's early residents and landowners include Whatley Crescent named after Anne and John Whatley, Hamilton Street named after John Hamilton, Copley Street named after Benjamin Copley, and Drake Street named after Henry Drake. Another origin of many street names in Bayswater is towns and streets in England, such as Almondbury Street, Arundel Street, Clavering Street or Shaftesbury Avenue.[4]

Bayswater lies on the Bassendean Dunes, which formed 800,000 to 125,000 years ago during the middle Pleistocene. The dunes form low-lying hills made of heavily leached white to grey sands, which are poor at retaining nutrients. Groundwater is about 10 m (33 ft) below the surface. The Bassendean Dunes are a part of the greater Swan Coastal Plain.[4][44][45]

Bayswater Brook was a natural brook that ran through Bayswater and nearby suburbs, linking various swamps and creeks in the area. In the 1920s, it was modified because of development into a network of drainage channels, with some covered and some open sections. The brook discharges into the Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary, which discharges into the Swan River.[46][47][48][49] The Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary is an artificial wetland, created after the surrounding area was used as a landfill between 1972 and 1981. The wetland had significant environmental problems until it was rehabilitated in 2015.[50][51] Nearby is Gobba Lake, an artificial deepwater lake named after Gino Gobba, a former City of Bayswater councillor. It was made for a clay pit used by Walkenden's Brickworks. Gobba Lake also underwent rehabilitation to make it more attractive to flora and fauna, and better for human recreational use.[10]

Erosion of the Swan River foreshore due to boat traffic is a problem in Bayswater. At least 5 m (16 ft) of erosion has occurred between 1995 and 2020. The City of Bayswater is currently funding works to prevent and fix erosion that has occurred.[52]

Demographics[]

Bayswater's population, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics' 2016 census, was 14,432,[1] an increase over the 13,525 recorded in the 2011 census.[53]

49.1% of residents are male, 50.9% are female. The median age is 38, which is above the Western Australian average of 36, and 44.3% of residents over the age of 15 are married, which is below the state average of 48.8%. Of the suburb's 6,263 dwellings, 5,604 were occupied, 659 were vacant. Of the 5,604 occupied dwellings, 4,387 were detached houses, 1,007 were semi-detached and 196 were apartments or flats. 1,491 were owned outright, 2,309 were owned with a mortgage, 1,586 were rented and 229 were other or not stated. Bayswater's tenure statistics closely align with the state averages.[1] The median weekly household income was $1,705, which is higher than the state and the country, which are at $1,595 and $1,438, respectively.[1] Major industries that residents worked in were school education (4.7%), cafés, restaurants and takeaway food services (4.5%), architectural, engineering and technical services (4.0%), hospitals (3.7%), and state government administration (3.7%). 4% of residents are unemployed, which is below the 2011 state average of 4.7%.[53][needs update]

The population of Bayswater is predominantly Australian born, 62.5% of residents, which is around the state average of 62.9%. The next-most-common birthplaces were England (7.0%), New Zealand (2.9%), India (2.9%), Italy (1.6%), and Vietnam (1.2%).[53][needs update]

The most common religious affiliations were no religion, with 28.6%, Roman Catholicism (27.4%), Anglicanism (14.9%), Uniting Church (2.7%), and Buddhism (2.4%). Churches in Bayswater include Saint Columba's Catholic Church, an Apostolic Church, and a Russian Orthodox Church, which is the only one in Perth.[53][9][needs update]

Parks and Amenities[]

Bayswater has a small town centre around the intersection of Whatley Crescent and King William Street. Amenities there include the Bayswater Library and Community Centre, a Bendigo Bank community branch, a post office, a WA Police station, a hotel and various small businesses. Businesses along Guildford Road include Muzz Buzz, Red Rooster, a Mazda dealer and a car rental. Businesses and services in the industrial area in Bayswater's east include a Bunnings Warehouse and the Baywaste Transfer Station, run by Cleanaway. The nearest shopping centre to Bayswater is the Galleria in Morley. Other shopping precincts are in Bassendean, Inglewood and Maylands, all have major supermarkets.

Lining the Swan River in Bayswater are various parks and reserves. Starting from the west, the 16.4 ha (41-acre) Baigup Wetlands are one of the last remaining areas of natural bushland along the Swan River's estuary and an important habitat for birds.[9][54] A.P. Hinds Reserve is home to ANA Rowing Club,[55] Bayswater Paddlesports Club and Bayswater Sea Scouts. is a popular park for dogs and picnics, and has a playground, boat ramp, café and a large open grassed area.[56][57] Annual events held here include the Autumn River Festival and the finish line of the Avon Descent, both of which involve food stalls and entertainment.[58][59] Nearby is the heritage listed Ellis House, restored by the City of Bayswater, and now a community art centre.[60][61] Next to Riverside Gardens is the Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary, an artificial wetland and bird habitat,[62] and on the other side of Tonkin Highway is Claughton Reserve, a large park with a boat ramp and playground.[63]

On the corner of Whatley Crescent and Garratt Road is the Frank Drago Reserve, home to the Bayswater City Soccer Club, Bayswater Bowls and Recreation Club, Bayswater Croquet Club and Bayswater Tennis Club.[64] In the suburb's town centre, there is Bert Wright Park, which hosts the Bayswater Growers' Market every Saturday,[65][66] and , which is home to the Bayswater Lacrosse Club and AIM Over 50 Archery Club,[67] and has a war memorial where an annual Anzac Day dawn service is held.[68] Between Coode Street and Drake Street, near Hillcrest Primary School, is Hillcrest Reserve, which has three ovals for Australian rules football and cricket, floodlights, cricket nets and clubrooms. The reserve is split into Upper Hillcrest Reserve and Lower Hillcrest Reserve, and is home to several amateur and junior football and cricket clubs.[69][70]

Education[]

The first school to open in Bayswater was Bayswater Primary School, established in 1894 as the Bayswater State School on Murray Street, near the Bayswater town centre. It caters to 60 Kindergarten students and 370 students between Pre-Primary and Year 6 as of 2020. It became an independent public school in 2020,[71] and is listed on the City of Bayswater Local Heritage Survey.[9] The school received a bell from a railway locomotive in 1904. Used to call the children into class, it remains to this day, despite calls for modernisation and is the reason behind the school's motto "Ringing True".[5]: 58

In 1936, St Columba's School, a private Catholic primary school on Roberts Street, opened to students. It caters to almost 500 students from Pre-Kindergarten to Year 6.[72] The church on the site is listed on the City of Bayswater Local Heritage Survey.[9]

The third school and second public school to open in Bayswater is Hillcrest Primary School, which opened in 1950. On Bay View Street, atop the crest of a large hill, it caters to 61 Kindergarten students and 364 Pre-Primary to Year 6 students as of 2020. It became an independent public school in 2020.[73] The school is listed on the City of Bayswater Local Heritage Survey.[9]

In 1985, Durham Road School opened in Bayswater. This school caters to students with intellectual and physical disabilities from Kindergarten to Year 12, serving students from all over Perth. The school had 200 students as of 2020.[74]

There are no secondary schools in Bayswater, but parts of the suburb are in the local intake areas for John Forrest Secondary College and Hampton Senior High School, both of which are independent public schools in Morley for students in Years 7 to 12. Also, just north of the suburb boundary with Bedford is Chisholm Catholic College, a private Catholic high school.

Governance[]

Local[]

Bayswater is in the City of Bayswater local government area. It lies mostly within the City's west ward, although there is a small portion of the suburb within its central ward.[2] Elections are held on the third Saturday of October in every odd year, and councillors are elected to four-year terms.[75] Councillors for the west ward are Lorna Clarke and Giorgia Johnson, whose terms expire in 2025, and Dan Bull, who is also the mayor and whose term expires in 2023. Councillors for the central ward are Assunta Meleca, whose term expires in 2025, and Sally Palmer and Steven Ostaszewskyj, whose terms expire in 2023.[76] Between 1897 and 1983, the suburb of Bayswater was the council seat of the City of Bayswater, which was known then as the Bayswater Road Board and later as the Shire of Bayswater.[4]

State[]

Bayswater west of Tonkin Highway is within the Electoral district of Maylands, and east of Tonkin Highway is within the Electoral district of Bassendean of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly.[77] Both districts are strong seats for the centre-left Labor Party. Labor has held Maylands since 1968 and Bassendean since it was created in 1996. Maylands' current member is Lisa Baker, and Bassendean's current member is Dave Kelly.[78][79] In the Western Australian Legislative Council, both districts are part of the East Metropolitan electoral region.

Bayswater has two polling locations: The Senior Citizens Centre and Hillcrest Primary School. The results below combine the results of these two polling places.

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Federal[]

Bayswater is within the Division of Perth in the Australian Federal Government.[86] It is a safe seat for the Australian Labor Party, and has been held by a Labor member since 1983. Its current member is Patrick Gorman. The results below combine the results of Bayswater's two polling places, Hillcrest Primary School and the Senior Citizens Centre.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transport[]

Cars are the most popular mode of transport in Bayswater. The 2011 Census revealed that 62.9% of residents travelled to work in a car. However, bicycle and public transport usage is significantly above the state averages. 15.6% of Bayswater residents said they take public transport to work; the state average is 9.4%, and 2.7% ride a bicycle to work; the state average is 1.1%.[53]

Road[]

The arterial roads which service Bayswater are Tonkin Highway, Guildford Road, Beechboro Road North, Garratt Road and Grand Promenade. Tonkin Highway is a north–south controlled access highway. Heading north on Tonkin Highway leads to Ellenbrook (20 km (12 mi)) and Joondalup (32 km (20 mi)) via Reid Highway. Heading south, the Redcliffe Bridge carries Tonkin Highway over the Swan River, which leads to Perth Airport, Armadale (33 km (21 mi)) and Roe Highway. The only other bridge over the Swan River in Bayswater is Garratt Road Bridge, which leads to Ascot and Belmont (6 km (3.7 mi)). Heading south west on Guildford Road leads to Maylands and the Perth CBD (6 km (3.7 mi)). Heading north-west on Guildford Road leads to Bassendean (4 km (2.5 mi)), Guildford (7 km (4.3 mi)) and Midland (11 km (6.8 mi)). Grand Promenade heads north-west of Bayswater and connects to Alexander Drive, Morley Drive and Dianella. Beechboro Road North heads north of Bayswater, leading to Beechboro and Malaga.[42]

Local distributor roads in Bayswater include Beechboro Road South, Collier Road, Coode Street, King William Street, Walter Road East and Whatley Crescent. Whatley Crescent goes through the town centre and connects to Guildford Road west of Bayswater as another connection to the Perth CBD. Collier Road connects the Bayswater industrial area to Tonkin Highway and Guildford Road, as well as linking Bayswater to the Morley commercial precinct. Beechboro Road South connects the town centre and the industrial area to Broun Avenue, north of Bayswater.[42]

King William Street is the main street through the town centre and the most direct connection between it and Guildford Road. Coode Street connects the town centre to Morley in the north. King William Street and Coode Street connect by an underpass under the railway line. The rail bridge at the underpass is known as the Bayswater Subway or Bayswater Bridge and is notorious for being hit by tall vehicles. There are three other railway line crossings in Bayswater. They are, from east to west, a level crossing connecting Railway Parade and Guildford Road, a bridge carrying Tonkin Highway over the railway line and a bridge connecting Railway Parade and Whatley Crescent near Meltham station. There are four crossings of Tonkin Highway in Bayswater, two of which have an interchange with Tonkin Highway. They are, from north to south, Collier Road, which bridges over the highway and connects as a single-point urban interchange, Railway Parade, which passes under a bridge, Guildford Road, which passes under a bridge and connects as a folded diamond interchange, and Dunstone Road, a minor road which passes under a bridge.[42]

Train[]

Bayswater is serviced by Bayswater and Meltham stations on the Midland railway line, with commuter services operated by Transperth between Midland and Perth. The currently under construction Airport railway line branches off from the Midland line in Bayswater. When it opens in the first half of 2022, it will connect Bayswater to Perth Airport and High Wycombe.[102] In addition, the Morley–Ellenbrook railway line is currently under planning, set to branch off from the Midland line at Bayswater as well. It is scheduled to open in 2023, creating a public transport connection between Bayswater and Perth's outer north-eastern suburbs.[103] As part of the Morley-Ellenbrook line project, Morley railway station is set to be constructed just north of Bayswater, which will improve public transport coverage to north-eastern parts of the suburb when it opens.[104] Whatley railway station, in the eastern part of Bayswater near the intersection of Wyatt Road and Higgins Way, was demolished in 1957 following the closure of the Belmont railway line in 1956.

Bus[]

Transperth bus services in Bayswater include routes 41, 48, 55, 341, 342, 955, 998 and 999. They are operated by Path Transit under contract from Transperth. Path Transit also operates a bus depot in Bayswater. Routes 41, 48 and 55 heading south-west lead to the Perth CBD. In Bayswater, route 41 travels along local streets south of Guildford Road, terminating at Leake Street. Route 48 travels along Guildford Road and King William Street, connecting to Bayswater railway station. North of there, route 48 links to Morley bus station, traversing minor roads along the way. Route 55 travels down Guildford Road and links to Bassendean railway station.[105] Routes 341 and 342 traverse the northern boundary of Bayswater at Walter Road. To the west, they connect to Morley bus station. To the east, they connect to Bassendean railway station and several north-eastern suburbs, including Beechboro.[106] Route 955 travels along Collier Road. To the west, it connects to Morley bus station. To the east, it connects to Bassendean railway station, before heading north to Ellenbrook.[107] Routes 998 and 999, also known as the CircleRoute are a pair of high frequency bus routes which travel in a circuit around Perth. Their route through Bayswater consists of Garratt Road, Guildford Road, King William Street and Coode Street. They have a connection at Bayswater railway station. 998 travels south through Bayswater, and 999 travels north through Bayswater. The CircleRoute provides a connection to Morley bus station, Dianella Plaza and Stirling railway station to the north, and Ascot Racecourse, Belmont Forum and Oats Street railway station to the south.[108]

Cycling[]

Bayswater is well connected by Principal Shared Paths (PSP's). The Midland Railway Line has a PSP alongside it, which leads to the Perth CBD to the west and Midland to the east.[109] Tonkin Highway has a PSP alongside it north of Railway Parade, constructed in 2017 as part of NorthLink WA.[110][111] There is also a PSP along the river used for recreational cycling.

In 2015, Leake and May Streets were selected to become Perth's first bike boulevards. The speed limit on the bike boulevard is 30 km/h (19 mph), below the standard 50 km/h (31 mph) limit in Australia. Cars are slowed by traffic calming measures. The bike boulevard encourages cycling in the area by linking the river, Bayswater Primary School and the Perth–Midland PSP.[112] The bike boulevard opened in March 2017.[113] In April 2018, the City of Bayswater decided not to go ahead with stage two of the bike boulevard, which would have seen the bike boulevard extended north through Bedford and Morley.[114]

References[]

- ^ a b c d "2016 Census QuickStats: Bayswater". Census Data. Australia Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Suburb Profiles" (PDF). City of Bayswater. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Indigenous history of the Swan and Canning rivers" (PDF). Department of Parks and Wildlife. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Bayswater Thematic Framework April 2020". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax May, Catherine (2013). Changes they've seen : the city and people of Bayswater 1827-2013. Morley, W.A.: City of Bayswater. ISBN 9780646596082.

- ^ "The Diary of Anne Whatley". The West Australian. XLVI (8, 671). Western Australia. 5 April 1930. p. 5. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The City's Logo". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "THE W.A. TURF CLUB". The West Australian. 2 (5). Western Australia. 6 January 1886. p. 3. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Local Heritage Survey". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Gobba Lake". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Progressive Bayswater". The West Australian. XXV (7, 162). Western Australia. 9 March 1909. p. 2. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "1911 Census – Volume III" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. p. 204. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "2021 Census – Population, and Occupied Dwellings in Localities" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "New Townsites". The West Australian. 53 (15, 937). Western Australia. 27 July 1937. p. 15. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c Lim, Kristie. "Proposed Meltham suburb rename in the works". PerthNow. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b "History of the name "Meltham"". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b Stephenson, Gordon.; Hepburn, J. A. (1955), Plan for the metropolitan region, Perth and Fremantle, Western Australia, 1955 : a report prepared for the Government of Western Australia, Perth: Government Printing Office, nla.obj-745050840, archived from the original on 6 June 2021, retrieved 6 June 2021 – via Trove

- ^ "Metropolitan Region Scheme Map 13" (PDF). Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Proposed Riverside Gardens (West) Dredging and Landfill King William Street, Bayswater" (PDF). Environmental Protection Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Mertome Retirement Village Development". City of Bayswater. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ a b Edmonds, Leigh (1997). The Vital Link: A History of Main Roads Western Australia 1926–1996. Nedlands, Western Australia: University of Western Australia Press. ISBN 1-876268-06-9.

- ^ "Major Metropolitan Road Network Changes" (PDF). Major Network Changes. Main Roads Western Australia. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Structure Plan for Bayswater - November 2015". Engage Bayswater. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater Town Centre Structure Plan". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Draft Structure Plan to Council". Engage Bayswater. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Have your say on the Draft Structure Plan". Engage Bayswater. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "New METRONET East Redevelopment Area to help create vibrant centres". Media Statements. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Young, Emma. "State to wrest control from Bayswater, Kalamunda councils' Metronet areas". WA Today. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "New METRONET precincts to unlock potential of Perth's east". DevelopmentWA. 20 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "METRONET East boundaries confirmed". Metronet. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Draft redevelopment scheme for METRONET East released". Media Statements. 6 August 2020. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "METRONET East: Overview". DevelopmentWA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "METRONET East Redevelopment Scheme sets vision for vibrant station precincts". Media Statements. 27 May 2021. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Metronet East Redevelopment Scheme". DevelopmentWA. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "METRONET East-Bayswater Draft Design Guidelines open for public comment". Metronet. 15 July 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Metronet East Bayswater Project Area Design Guidelines draft" (PDF). DevelopmentWA. July 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Meltham Suburb". Engage Bayswater. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Locals happy with height for trees". The Perth Voice Interactive. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Pascual Juanola, Marta. "Why one Perth council has heritage listed its entire town centre". WA Today. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "New plan for Bayswater Town Centre sets vision for growth". Mirage News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "New plan for Bayswater Town Centre sets vision for growth". Media Statements. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Google Maps". Google. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Metropolitan Region Scheme Map 16" (PDF). Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Geomorphology of Swan Coastal Plain". Garry Middle. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Swan Coastal Plain - Reading". Earth Science WA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater Brook Local Water Quality Improvement Plan" (PDF). Department of Water and Environmental Regulation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater Brook" (PDF). Department of Water and Environmental Regulation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater Brook Brochure" (PDF). Urban Bushland Council WA Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater Brook Catchment". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary". Urban Bushland Council WA Inc. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Lim, Kristie. "City of Bayswater plan to improve Swan River foreshore". Perth Now. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "2011 Census QuickStats: Bayswater". Census Data. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Baigup Wetlands". Urban Bushland Council WA Inc. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Rowing and Yachting". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Riverside Gardens". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "The Best Dog Beaches in Perth". So Perth. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Autumn River Festival". The Perth Voice Interactive. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Lim, Kristie. "City of Bayswater to host annual Avon Descent Finish Line event at Riverside Gardens". Perth Now. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Ellis House Community Art Centre". Ellis House Community Art Centre. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Ellis House - Historical Site". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Eric Singleton Bird Sanctuary". Urban Bushland Council WA Inc. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Claughton Reserve". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Frank Drago Reserve". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Hancock, Peter. "Bayswater Growers' Market". Weekend Notes. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Prestipino, David. "Fresh Bites: Oktoberfest comes to town, Pirate Life brewery to open in Perth". WAtoday. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Halliday Park". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Bayswater War Memorial & Memorial Rose Gardens". Heritage Council of WA. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Lower Hillcrest Reserve". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Upper Hillcrest Reserve". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Bayswater Primary School (5031)". Schools Online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "History". St Columba's School. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Hillcrest Primary School (5209)". Schools Online. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Durham Road School (6029)". Schools Online. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Council Elections". City of Bayswater. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Elected Members". City of Bayswater. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Find Your Electorate". Electoral Boundaries WA. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ "Maylands". ABC News. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ "Bassendean". ABC News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ "Maylands District Profile and Results". Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Maylands District Profile and Results". Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Maylands District Profile and Results". Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Maylands District Profile and Results". Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Maylands District Profile and Results". Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "SGE_DistrictProfiles_Alb-Avn" (PDF). Western Australian Electoral Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Locality Search". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Bayswater - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater North - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater North - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Bayswater North - polling place". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater North". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater North". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater North". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Polling Place - Bayswater North". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "WA : Perth". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Home". Forrestfield–Airport link. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Project Features – Morley-Ellenbrook Line". Metronet. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Morley Station Fact Sheet" (PDF). Metronet. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Bus Timetable 103" (PDF). Transperth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Bus Timetable 104" (PDF). Transperth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Bus Timetable 99" (PDF). Transperth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Bus Timetable 200" (PDF). Transperth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Perth to Midland Bike Route" (PDF). Department of Transport. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Southern Section". Main Roads Western Australia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Major Cycle and Pedestrian Paths" (PDF). Bicycling Western Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Beattie, Adrian (4 October 2015). "Perth's bicycle boulevards - where cyclists get priority over cars". WA Today. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Shakespeare, Toyah (21 March 2017). "Bayswater bike boulevard connects suburb to Morley". Eastern Reporter. Community News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "City of Bayswater flat on enthusiasm for Bayswater to Morley Bike Boulevard project stage 2". Perth Now. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Bayswater, Western Australia

- Suburbs of Perth, Western Australia

- Suburbs in the City of Bayswater