Espresso

A cup of espresso from Ventimiglia, Italy | |

| Type | Hot |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Italy |

| Introduced | 1901 |

| Color | Black |

Espresso (/ɛˈsprɛsoʊ/ (![]() listen), Italian: [eˈsprɛsso]) is a coffee-brewing method of Italian origin,[1] in which a small amount of nearly boiling water (about 90 °C or 190 °F) is forced under 9–10 bars (900–1,000 kPa; 130–150 psi) of pressure (expressed) through finely-ground coffee beans. Espresso coffee can be made with a wide variety of coffee beans and roast degrees. Espresso is the most common way of making coffee in southern Europe, especially in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Southern France and Bulgaria.

listen), Italian: [eˈsprɛsso]) is a coffee-brewing method of Italian origin,[1] in which a small amount of nearly boiling water (about 90 °C or 190 °F) is forced under 9–10 bars (900–1,000 kPa; 130–150 psi) of pressure (expressed) through finely-ground coffee beans. Espresso coffee can be made with a wide variety of coffee beans and roast degrees. Espresso is the most common way of making coffee in southern Europe, especially in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Southern France and Bulgaria.

Espresso is generally thicker than coffee brewed by other methods, with a viscosity of warm honey. This is due to the higher concentration of suspended and dissolved solids, and the crema on top (a foam with a creamy consistency).[2] As a result of the pressurized brewing process, the flavors and chemicals in a typical cup of espresso are very concentrated. The three dispersed phases in espresso are what make this beverage unique. The first dispersed phase is an emulsion of oil droplets. The second phase is suspended solids, while the third is the layer of gas bubbles or foam. The dispersion of very small oil droplets is perceived in the mouth as creamy. This characteristic of espresso contributes to what is known as the body of the beverage. These oil droplets preserve some of the aromatic compounds that are lost to the air in other coffee forms. This preserves the strong coffee flavor present in the espresso.[3] Espresso is also the base for various coffee drinks—including caffè latte, cappuccino, caffè macchiato, caffè mocha, flat white, and caffè Americano.

Espresso has more caffeine per unit volume than most coffee beverages, but because the usual serving size is much smaller, the total caffeine content is less than a mug of standard brewed coffee.[4] The actual caffeine content of any coffee drink varies by size, bean origin, roast method and other factors, but a typical 28 grams (1 ounce) serving of espresso usually contains 65 milligrams of caffeine, whereas a typical serving of drip coffee usually contains 150 to 200 mg.[5][6][7]

Brewing[]

Espresso is made by forcing very hot water under high pressure through finely ground compacted coffee. Tamping down the coffee promotes the water's even penetration through the grounds.[8] This process produces an almost syrupy beverage by extracting both solid and dissolved components. The crema[9][10] is produced by emulsifying the oils in the ground coffee into a colloid, which does not occur in other brewing methods. There is no universal standard defining the process of extracting espresso,[11] but several published definitions attempt to constrain the amount and type of ground coffee used, the temperature and pressure of the water, and the rate of extraction.[12][13] Generally, one uses an espresso machine to make espresso. The act of producing a shot of espresso is often called "pulling" a shot, originating from lever espresso machines, with which a barista pulls down a handle attached to a spring-loaded piston, which forces hot water through the coffee at high pressure. Today, however, it is more common for an electric pump to generate the pressure.

The technical parameters outlined by the Italian Espresso National Institute for making a "certified Italian espresso" are:[14]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Portion of ground coffee | 7 ± 0.5 g (0.25 ± 0.02 oz) |

| Exit temperature of water from unit | 88 ± 2 °C (190 ± 4 °F) |

| Temperature in cup | 67 ± 3 °C (153 ± 5 °F) |

| Entry water pressure | 9 ± 1 bar (900 ± 100 kPa; 131 ± 15 psi) |

| Percolation time | 25 ± 5 seconds |

| Volume in cup (including crema) | 25 ± 2.5 ml (0.88 ± 0.09 imp fl oz; 0.85 ± 0.08 US fl oz) |

Espresso roast[]

Espresso is both a coffee beverage and a brewing method. It is not a specific bean, bean blend, or roast level. Any bean or roasting level can be used to produce authentic espresso. For example, in southern Italy, a darker roast is generally preferred. Farther north, the trend moves toward slightly lighter roasts, while outside Italy a wide range is popular.[15]

History[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

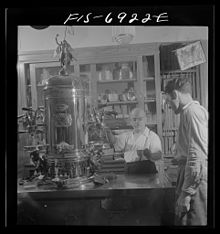

Angelo Moriondo, from Turin, patented a steam-driven "instantaneous" coffee beverage making device in 1884 (No. 33/256). The device is "almost certainly the first Italian bar machine that controlled the supply of steam and water separately through the coffee" and Moriondo is "certainly one of the earliest discoverers of the expresso [sic] machine, if not the earliest".[16] Unlike true espresso machines, it brewed in bulk, not as individual servings. Seventeen years later, in 1901, Luigi Bezzera, from Milan, devised and patented several improvements to the espresso machine, the first of which was applied for on 19 December 1901. Titled "Innovations in the machinery to prepare and immediately serve coffee beverage"; Patent No. 153/94, 61707, was granted on 5 June 1902. In 1903, the patent was bought by Desiderio Pavoni, who founded the La Pavoni company and began to produce the machine industrially, manufacturing one machine daily in a small workshop in Via Parini, Milan.[17]

The popularity of espresso developed in various ways; a detailed discussion of the spread of espresso is given in (Morris 2007), which is a source of various statements below. In Italy, the rise of espresso consumption was associated with urbanization, espresso bars providing a place for socializing. Further, coffee prices were controlled by local authorities, provided the coffee was consumed standing up, encouraging the "stand at a bar" culture.

In the English-speaking world, espresso became popular, particularly in the form of cappuccino, owing to the tradition of drinking coffee with milk and the exotic appeal of the foam; in the United States, this was more often in the form of lattes, with or without flavored syrups added. The latte is claimed to have been invented in the 1950s by Italian American Lino Meiorin of Caffe Mediterraneum in Berkeley, California, as a long cappuccino, and was then popularized in Seattle,[18] and then nationally and internationally by Seattle-based Starbucks in the late 1980s and 1990s.

In the United Kingdom, espresso grew in popularity among youth in the 1950s, who felt more welcome in the coffee shops than in pubs. Espresso was initially popular, particularly within the Italian diaspora, growing in popularity with tourism to Italy exposing others to espresso, as developed by Eiscafès established by Italians in Germany. Initially, expatriate Italian espresso bars were seen as downmarket venues, serving the working-class Italian diaspora and thus providing appeal to the alternative subculture; this can still be seen in the United States in Italian American neighborhoods, such as Boston's North End, New York's Little Italy, and San Francisco's North Beach. As specialty coffee developed in the 1980s (following earlier developments in the 1970s and even 1960s), an indigenous artisanal coffee culture developed, with espresso instead positioned as an upmarket drink.

In the 2010s, coffee culture commentators distinguish large-chain mid-market coffee as "Second Wave Coffee", and upmarket artisanal coffee as "Third Wave Coffee". In the Middle East and Asia, espresso is growing in popularity, with the opening of Western coffee-shop chains.[19][self-published source?]

Trieste is the seat of the Universita del Caffe, founded by Illy in 1999. This center of excellence was created to spread the quality coffee culture through training across the world, educate barrista, and conduct research and innovation. Particular attention is paid to the preparation of the espresso and the relevant scientific research. It is also about the correct interaction of coffee and espresso machine.[20]

Café vs. home preparation[]

Home espresso machines have increased in popularity with the general rise of interest in espresso. Today, a wide range of home espresso equipment can be found in kitchen and appliance stores, online vendors, and department stores. The first espresso machine for home use was the Gaggia Gilda.[21] Soon afterwards, similar machines such as the Faema Faemina, FE-AR La Peppina and VAM Caravel followed suit in similar form factor and operational principles.[22] These machines still have a small but dedicated share of fans. Until the advent of the first small electrical pump-based espresso machines such as the Gaggia Baby and Quickmill 810, home espresso machines were not widely adopted. In recent years, the increased availability of convenient counter-top fully automatic home espresso makers and pod-based espresso serving systems has increased the quantity of espresso consumed at home. The popularity of home espresso making parallels the increase of home coffee roasting. Some amateurs pursue both home roasting coffee and making espresso.

Etymology and spelling[]

Some English dictionaries translate espresso as "pressed-out",[23] but the word also conveys the senses of expressly for you and quickly:

The words express, expres and espresso each have several meanings in English, French and Italian. The first meaning is to do with the idea of "expressing" or squeezing the flavour from the coffee using the pressure of the steam. The second meaning is to do with speed, as in a train. Finally there is the notion of doing something "expressly" for a person ... The first Bezzera and Pavoni espresso machines in 1906 took 45 seconds to make a cup of coffee, one at a time, expressly for you.[24]

Modern espresso, using hot water under pressure, as pioneered by Gaggia in the 1940s, was originally called crema caffè (in English, "cream coffee") as seen on old Gaggia machines, due to the crema.[25] This term is no longer used, though crema caffè and variants (caffè crema, café crema) still appear in branding.

Variant spelling[]

The spelling expresso is mostly considered incorrect, though some sources call it a less common variant.[26] Italy uses the term espresso, substituting s for most x letters in Latin-root words; x is not considered part of the standard Italian alphabet. Italian people commonly refer to it simply as caffè (coffee), espresso being the ordinary coffee to order; in Spain, while café expreso is seen as the more "formal" denomination, café solo (alone, without milk) is the usual way to ask for it when at an espresso bar.

Some sources state that expresso is an incorrect spelling, including Garner's Modern American Usage.[27] While the 'expresso' spelling is recognized as mainstream usage in some American dictionaries,[28][29] some cooking websites call the 'x' variant illegitimate.[30][31][32] Oxford Dictionaries online states "The spelling "expresso" is not used in the original Italian and is strictly incorrect, although it is common."[33] The Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster call it a variant spelling.[27][34] The Online Etymology Dictionary calls "expresso" a variant of "espresso".[35] The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style (2000) describes the spelling expresso as "wrong", and specifies espresso as the only correct form.[36] The third edition of Fowler's Modern English Usage, published by the Oxford University Press in 1996, noted that the form espresso "has entirely driven out the variant expresso (which was presumably invented under the impression that it meant 'fast, express')".[37]

Shot variables[]

The main variables in a shot of espresso are the "size" and "length".[38][39] This terminology is standardized, but the precise sizes and proportions vary substantially.

Cafés may have a standardized shot (size and length), such as "triple ristretto",[39] only varying the number of shots in espresso-based drinks such as lattes, but not changing the extraction – changing between a double and a triple requires changing the filter basket size, while changing between ristretto, normale, and lungo may require changing the grind, which is less easily accommodated in a busy café.

Size[]

The size can be a single, double, or triple, using a proportional amount of ground coffee, roughly 7, 14, and 21 grams; correspondingly sized filter baskets are used. The Italian multiplier term doppio is often used for a double, with solo and triplo being more rarely used for singles and triples. The single shot is the traditional shot size, being the maximum that could easily be pulled on a lever machine.

Single baskets are sharply tapered or stepped down in diameter to provide comparable depth to the double baskets and, therefore, comparable resistance to water pressure. Most double baskets are gently tapered (the "Faema model"), while others, such as the La Marzocco, have straight sides. Triple baskets are normally straight-sided.

Portafilters will often come with two spouts, usually closely spaced, and a double-size basket – each spout can optionally dispense into a separate cup, yielding two solo-size (but doppio-brewed) shots, or into a single cup (hence the close spacing). True solo shots are rare, with a single shot in a café generally being half of a doppio shot.

In espresso-based drinks in America, particularly larger milk-based drinks, a drink with three or four shots of espresso will be called a "triple" or "quad", respectively.

Length[]

The length of the shot can be ristretto (or stretto) (reduced), normale or standard (normal), or lungo (long):[40] these may correspond to a smaller or larger drink with the same amount of ground coffee and same level of extraction or to different length of extraction. Proportions vary and the volume (and low density) of crema make volume-based comparisons difficult (precise measurement uses the mass of the drink). Typically ristretto is half the volume of normale, and lungo is double to triple the normale volume. For a double shot, (14 grams of dry coffee), a normale uses about 60 ml of water. A double ristretto, a common form associated with espresso, uses half the amount of water, about 30 ml.

Ristretto, normale, and lungo may not simply be the same shot, stopped at different times[citation needed]—which may result in an under-extracted shot (if run too short a time) or an over-extracted shot (if run too long a time).[citation needed] Rather, the grind is adjusted (finer for ristretto, coarser for lungo) so the target volume is achieved by the time extraction finishes.

A significantly longer shot is the caffè crema, which is longer than a lungo, ranging in size from 120–240 ml (4.2–8.4 imp fl oz; 4.1–8.1 US fl oz), and brewed in the same way, with a coarser grind.

The method of adding hot water produces a milder version of original flavor, while passing more water through the load of ground coffee will add other flavors to the espresso, which might be unpleasant for some people.

Variations[]

Caffè Freddo[]

In Greece, Cyprus, and neighbouring countries in southern Europe, a cold espresso is a Caffè Freddo or Freddo Espresso. Despite its Italian name, the drink is prepared differently from its Italian counterpart. Conceived in Greece, along with freddo cappuccino in 1991, freddo espresso is in higher demand during summer.[41][42] After 2 shots of espresso (usually ristretto) are prepared, the coffee is stirred in a big metal can along with sugar (if desired) and 2–3 ice cubes until the coffee is cold. Then the blend is served in a glass with additional ice.

Short (or short) coffee[]

It is obtained simply by letting less liquid flow into the cup, so as to extract only the first fractions of the coffee powder from the ground coffee powder. The result is a coffee that has intensity, body and aromatic finesse and is also more dense (creamy). The concentration of caffeine is very low. Pressure 9-10 bar, 18-25 milliliters.

Long coffee[]

Obtained by letting more water flow into the cup, the result is a coffee with a greater dilution that presents different aromatic finesse, due to the greater extraction of substances, a pronounced bitterness and a higher caffeine content. Pressure 9-10 bar, 35-50 milliliters.

Macchiato coffee[]

It is obtained by adding a small amount of milk , cold or hot, therefore the freshly prepared espresso is called cold macchiato or hot macchiato (in this case the added milk is frothed). In addition to milk it is used, albeit less frequently, cream .

Coffee with cream[]

Coffee with cream or espresso with cream is espresso topped with whipped cream , usually served in a coffee cup

Proper Coffee[]

Correct coffee is a common definition used to indicate an espresso coffee with the addition of a small amount of a spirit to be specified when ordering; usually grappa or sambuca is used ; the coffee can be served in a cup (or small glass) with a lot of alcohol already poured, or with separate alcohol. In Spain, there is the corresponding carajillo , also obtainable with different types of corrections.

Rexentìn[]

In Veneto there is the custom of making the so-called "rexentìn" (or also "raxentìn" in some areas), or rinsing: after drinking the correct coffee, a small amount of drink remains on the bottom of the cup, which is cleaned by pouring and drinking some of the alcohol used for correction. In Trentino-Alto Adige this custom is widespread, called resentìn , only with mocha coffee.

Decaffeinated coffee[]

Espresso whose unroasted beans have undergone a caffeine extraction process before being roasted, ground and used to extract the drink (see decaffeinated coffee ).

Portuguese coffee[]

A variant halfway between the Italian restricted and the French espresso is the so-called Portuguese café , also called bica in the south of the country and bocolino in Porto .

Staccato Espresso[]

An espresso shot prepared using layers of either different sifted particle sizes or different grind sizes usually with the finer layer of grounds on the bottom.

Nutrition[]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 8.4 kJ (2.0 kcal) |

Carbohydrates | 0. |

Fat | 0.2 |

Protein | 0.1 |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 17% 0.2 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 35% 5.2 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Magnesium | 23% 80 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 97.8 g |

| Theobromine | 0 mg |

| Caffeine | 212 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Probably owing to the higher quantity of suspended solids—compared to typical coffee, which is absent of essential nutrients—espresso has significant levels of dietary mineral magnesium, the B vitamins niacin and riboflavin, and around 212 mg of caffeine per 100 grams of liquid brewed coffee (table).

Espresso-based drinks[]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2013) |

In addition to being served alone, espresso is frequently blended, notably with milk – either steamed (without significant foam), wet foamed ("microfoam"), or dry foamed, and with hot water. Notable milk-based espresso drinks, in order of size, include: macchiato, cappuccino, flat white, and latte; other milk and espresso combinations include latte macchiato, cortado and galão, which are made primarily with steamed milk with little or no foam. Espresso and water combinations include Americano and long black. Other combinations include batch-brewed coffee with espresso, sometimes called "red eye" or "shot in the dark".[43]

In order of size, these may be organized as follows:

- Traditional macchiato: 35–40 ml, one shot (30 ml) with a small amount of milk (mostly steamed, with slight foam so there is a visible mark)

- Modern macchiato: 60 ml or 120 ml, one or two shots (30 or 60 ml), with 1:1 milk

- Cortado: 60 ml, one shot with 1:1 milk, little foam

- Piccolo Latte: 90 ml, one shot with 1:2 milk, little foam

- Galão: 120 ml, one shot with 1:3 milk, little foam

- Flat white: 150 ml, one or two shots (30 or 60 ml), with 1:4 or 2:3 milk, and a small amount (usually 6 mm or 1⁄4 inch) microfoam.

- Cappuccino: a very popular frothed milk and espresso drink with no generally-accepted volume standards, but usually served at 120 to 160 ml, including a single or (more commonly) double shot of espresso.[44]

- Latte: 240–600 ml, two or more shots (60 ml), with 1:3–1:9 milk

- Dirty: 200 ml, about 150 ml cold milk, one or two shot of espresso pouring over the cold milk directly. Usually served with glass.[45]

Some common combinations may be organized graphically as follows:

| mixed with | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| frothed milk | hot water | ||

| espresso is on | top | latte macchiato | long black |

| bottom | caffè latte | caffè americano | |

Methods of preparation differ between drinks and between baristas. For macchiatos, cappuccino, flat white, and smaller lattes and Americanos, the espresso is brewed into the cup, then the milk or water is poured in. For larger drinks, where a tall glass will not fit under the brew head, the espresso is brewed into a small cup, then poured into the larger cup; for this purpose a demitasse or specialized espresso brew pitcher may be used. This "pouring into an existing glass" is a defining characteristic of the latte macchiato and classic renditions of the red eye. Alternatively, a glass with "existing" water may have espresso brewed into it – to preserve the crema – in the long black. Brewing onto milk is not generally done.

See also[]

- List of coffee drinks

- List of hot beverages

Coffee portal

Coffee portal

References[]

- Citations

- ^ "Espresso Coffee Maker Through History". EspressoCoffeeBrewers.com. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Illy, "Il caffè e i cinque sensi" [1]: "La tazzina di porcellana bianca incornicia la crema: una trama sottile nei toni del nocciola, percorsa da leggere striature rossastre"

- ^ Illy, Andrea (2005). Espresso Coffee: The Science of Quality. Elsevier Academic Press.

- ^ "The Great Debate: Does Espresso or Drip Coffee Have More Caffeine?". Mr. Coffee. 24 October 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Show Foods". Archived from the original on 24 November 2013.

- ^ How much caffeine is in your daily habit? – MayoClinic.com

- ^ "Show Foods". Archived from the original on 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Espresso Tamping". CoffeeResearch.org. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "What is Crema?". seattlecoffeegear. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "Espresso Crema". ChemistryViews.org. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Today's Espresso Scene". Home Barista. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Espresso Coffee". Coffee Research Institute. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "L'Espresso Italiano Certificato" (PDF). Istituto Nazionale Espresso Italiano. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Espresso Italiano Certificato" (PDF). Istituto Nazionale Espresso Italiano. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Illy, Francesco; Illy, Riccardo (1992). The book of coffee : a gourmet's guide (1st American ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-1558593213.

- ^ Bersten 1993, p. 105.

- ^ Stamp, Jimmy. "The Long History of the Espresso Machine". Smithsonian. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Invention of the Caffe Latte". Caffe Mediterraneum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ Hutchins, Timothy (3 July 2017). Coffee Culture. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781387074518.[self-published source]

- ^ Almut Siefert "Zu Besuch in der Kaffee-Universität in Triest. Eine Bohne kann alles verderben." In: Stuttgarter Zeitung, 27 September 2019.

- ^ Bersten 1993, p. 131.

- ^ Bersten 1993, p. 132-133.

- ^ "espresso". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University press. 1989. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ^ Bersten 1993, p. 99.

- ^ Morris 2007.

- ^ "Expresso - Define Expresso at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ben Yagoda (18 August 2014). "Espresso or expresso? The x spelling actually has considerable historical precedent". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Expresso – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-webster.com (13 August 2010). Retrieved on 13 February 2011.

- ^ Expresso | Define Expresso at Dictionary.com. Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved on 13 February 2011.

- ^ What is espresso? Or is it expresso?. Homecooking.about.com (14 June 2010). Retrieved on 13 February 2011.

- ^ What is Espresso. Espresso People. Retrieved on 13 February 2011. Archived 1 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Great Debate: Espresso vs. Expresso". Espresso Blog. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- ^ Definition of espresso from Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved on 13 February 2011.

- ^ "Expresso – Definition of Expresso by Merriam-Webster".

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ Garner 2000, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Burchfield 1996, p. 286.

- ^ "Brewing ratios for espresso beverages - Home-Barista.com".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anatomy of a Triple Ristretto Archived 9 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, by Jeremy Gauger, Gimme Coffee, 17 March 2009 – images and explanation

- ^ Hofmann, Paul (7 August 1983). "Fare of the Country: In Italy, Espresso is the Elixir of Life". Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Freddo Espresso & Freddo Cappuccino | Nespresso Hellas". www.nespresso.com. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Ήξερες ότι ο Freddo γεννήθηκε στην Ελλάδα;". www.news247.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Kevin, Sinnott (2010). The art and craft of coffee: an enthusiast's guide to selecting, roasting, and brewing exquisite coffee. Beverly, Mass.: Quarry Books. p. 160. ISBN 9781592535637. OCLC 437298903.

- ^ Ortved, John (29 September 2015). "Is That Cappuccino You're Drinking Really a Cappuccino?". The New York Times.

- ^ "What Is A Dirty Coffee?". Above Average Coffee. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Sources

- Bersten, Ian (1993). Coffee Floats Tea Sinks: Through History and Technology to a Complete Understanding. Helian Books. ISBN 0-646-09180-8.

- Burchfield, R. W. (1996). Fowler's Modern English Usage (third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869126-6.

- Garner, Bryan (2000). The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513508-4.

- Morris, Jonathan (2007), "The Cappuccino Conquests. The Transnational History of Italian Coffee", Academia.org, University of Hertfordshire

Further reading[]

- Davids, Kenneth (2013). Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, and Enjoying (5 ed.). St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1466854420.

- Fumagalli, Ambrogio (1995). Coffee Makers. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-1082-8.

- Illy, Andrea; Viani, Rinantonio (2005). Espresso: The Science of Quality. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-370371-9.

- Illy, Francesco; Illy, Riccardo (1989). The Book of Coffee. Milano: Abbeville Press. ISBN 1-55859-321-7.

- Schomer, David C. Espresso Coffee: Professional Techniques. 1996.

External links[]

- Espresso

- Coffee preparation

- Coffee drinks

- Hot drinks

- Italian cuisine

- Coffee culture

- Coffee in Italy