Ghent

Ghent

| |

|---|---|

View of Ghent from the Graslei | |

Flag Coat of arms | |

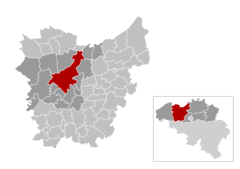

Ghent Location in Belgium

show Ghent in the province of East Flanders | |

| Coordinates: 51°03′13″N 03°43′31″E / 51.05361°N 3.72528°ECoordinates: 51°03′13″N 03°43′31″E / 51.05361°N 3.72528°E | |

| Country | Belgium |

| Community | Flemish Community |

| Region | Flemish Region |

| Province | East Flanders |

| Arrondissement | Ghent |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (list) | Mathias De Clercq |

| • Governing party/ies | Vooruit-Groen, Open VLD, CD&V |

| Area | |

| • Total | 156.18 km2 (60.30 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[1] | |

| • Total | 260,341 |

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,300/sq mi) |

| Postal codes | 9000–9052 |

| Area codes | 09 |

| Website | www.gent.be |

Ghent (/ɡɛnt/ GHENT; Dutch: Gent [ɣɛnt] (![]() listen); French: Gand [ɡɑ̃] (

listen); French: Gand [ɡɑ̃] (![]() listen); traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in size only by Brussels and Antwerp.[2] It is a port and university city.

listen); traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in size only by Brussels and Antwerp.[2] It is a port and university city.

The city originally started as a settlement at the confluence of the Rivers Scheldt and Leie and in the Late Middle Ages became one of the largest and richest cities of northern Europe, with some 50,000 people in 1300.

The municipality comprises the city of Ghent proper and the surrounding suburbs of Afsnee, Desteldonk, Drongen, Gentbrugge, Ledeberg, Mariakerke, Mendonk, Oostakker, Sint-Amandsberg, Sint-Denijs-Westrem, Sint-Kruis-Winkel, Wondelgem and Zwijnaarde. With 262,219 inhabitants at the beginning of 2019, Ghent is Belgium's second largest municipality by number of inhabitants. The metropolitan area, including the outer commuter zone, covers an area of 1,205 km2 (465 sq mi) and has a total population of 560,522 as of 1 January 2018, which ranks it as the fourth most populous in Belgium.[3][4] The current mayor of Ghent, Mathias De Clercq is from the liberal & democratic party Open VLD.

The ten-day-long Ghent Festival (Gentse Feesten in Dutch) is held every year and attended by about 1–1.5 million visitors.

History[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

Archaeological evidence shows human presence in the region of the confluence of Scheldt and Leie going back as far as the Stone Age and the Iron Age.[5]

Most historians believe that the older name for Ghent, 'Ganda', is derived from the Celtic word ganda which means confluence.[5] Other sources connect its name with an obscure deity named Gontia.[6]

There are no written records of the Roman period, but archaeological research confirms that the region of Ghent was further inhabited.

When the Franks invaded the Roman territories from the end of the 4th century and well into the 5th century, they brought their language with them and Celtic and Latin were replaced by Old Dutch.

Middle Ages[]

Around 650, Saint Amand founded two abbeys in Ghent: St. Peter's (Blandinium) and Saint Bavo's Abbey. Around 800, Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, appointed Einhard, the biographer of Charlemagne, as abbot of both abbeys. The city grew from several nuclei, the abbeys and a commercial centre. However, both in 851 and 879, the city was plundered by the Vikings.

Within the protection of the County of Flanders, the city recovered and flourished from the 11th century, growing to become a small city-state. By the 13th century, Ghent was the biggest city in Europe north of the Alps after Paris; it was bigger than Cologne or Moscow.[7] Within the city walls lived up to 65,000 people. The belfry and the towers of the Saint Bavo Cathedral and Saint Nicholas' Church are just a few examples of the skyline of the period.

The rivers flowed in an area where much land was periodically flooded. These rich grass 'meersen' ("water-meadows": a word related to the English 'marsh') were ideally suited for herding sheep, the wool of which was used for making cloth. During the Middle Ages Ghent was the leading city for cloth.

The wool industry, originally established at Bruges, created the first European industrialized zone in Ghent in the High Middle Ages. The mercantile zone was so highly developed that wool had to be imported from Scotland and England. This was one of the reasons for Flanders' good relationship with Scotland and England. Ghent was the birthplace of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Trade with England (but not Scotland) suffered significantly during the Hundred Years' War.

Early modern period[]

The city recovered in the 15th century, when Flanders was united with neighbouring provinces under the Dukes of Burgundy. High taxes led to a rebellion and eventually the Battle of Gavere in 1453, in which Ghent suffered a terrible defeat at the hands of Philip the Good. Around this time the centre of political and social importance in the Low Countries started to shift from Flanders (Bruges–Ghent) to Brabant (Antwerp–Brussels), although Ghent continued to play an important role. With Bruges, the city led two revolts against Maximilian of Austria, the first monarch of the House of Habsburg to rule Flanders.

In 1500, Juana of Castile gave birth to Charles V, who became Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. Although native to Ghent, he punished the city after the 1539 Revolt of Ghent and obliged the city's nobles to walk in front of the Emperor barefoot with a noose (Dutch: "strop") around the neck; since this incident, the people of Ghent have been called "Stroppendragers" (noose bearers). Saint Bavo Abbey (not to be confused with the nearby Saint Bavo Cathedral) was abolished, torn down, and replaced with a fortress for Royal Spanish troops. Only a small portion of the abbey was spared demolition.

The late 16th and the 17th centuries brought devastation because of the Eighty Years' War. The war ended the role of Ghent as a centre of international importance. In 1745, the city was captured by French forces during the War of the Austrian Succession before being returned to the Empire of Austria under the House of Habsburg following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, when this part of Flanders became known as the Austrian Netherlands until 1815, the exile of the French Emperor Napoleon I, the end of the French Revolutionary and later Napoleonic Wars and the peace treaties arrived at by the Congress of Vienna.

19th century[]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the textile industry flourished again in Ghent. Lieven Bauwens, having smuggled the industrial and factory machine plans out of England, introduced the first mechanical weaving machine on the European continent in 1800.

The Treaty of Ghent, negotiated here and adopted on Christmas Eve 1814, formally ended the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States (the North American phase of the Napoleonic Wars). After the Battle of Waterloo, Ghent and Flanders, previously ruled from the House of Habsburg in Vienna as the Austrian Netherlands, became a part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands with the northern Dutch for 15 years. In this period, Ghent established its own university (1816)[8] and a new connection to the sea (1824–27).

After the Belgian Revolution, with the loss of port access to the sea for more than a decade, the local economy collapsed and the first Belgian trade union originated in Ghent. In 1913 there was a world exhibition in Ghent.[8] As a preparation for these festivities, the Sint-Pieters railway station was completed in 1912.

20th century[]

Ghent was occupied by the Germans in both World Wars but escaped severe destruction. The life of the people and the German invaders in Ghent during World War I is described by H. Wandt in "etappenleven te Gent"[citation needed]. In World War II the city was liberated by the British 7th "Desert Rats" Armoured Division and local Belgian fighters on 6 September 1944, with the northern suburbs and the industrial area cleared over the following days by the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division.

Geography[]

After the fusions of municipalities in 1965 and 1977, the city is made up of:

- I Ghent

- II Mariakerke

- III Drongen

- IV Wondelgem

- V Sint-Amandsberg

- VI Oostakker

- VII Desteldonk

- VIII Mendonk

- IX Sint-Kruis-Winkel

- X Ledeberg

- XI Gentbrugge

- XII Afsnee

- XIII Sint-Denijs-Westrem

- XIV Zwijnaarde

Neighbouring municipalities[]

Climate[]

The climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Ghent has a marine west coast climate, abbreviated "Cfb" on climate maps.[9]

| hideClimate data for Ghent (1981–2010 normals, sunshine 1984–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.7 (2.78) |

56.2 (2.21) |

61.5 (2.42) |

50.6 (1.99) |

63.1 (2.48) |

74.3 (2.93) |

77.4 (3.05) |

84.2 (3.31) |

74.2 (2.92) |

81.7 (3.22) |

82.7 (3.26) |

82.2 (3.24) |

858.8 (33.81) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.6 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 136.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61 | 79 | 123 | 172 | 204 | 196 | 209 | 196 | 144 | 118 | 66 | 50 | 1,618 |

| Source: Royal Meteorological Institute[10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

Population[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2020) |

Nationalities[]

| 219,435 | |

| 7,512 | |

| 4,334 | |

| 2,815 | |

| 1,759 | |

| 1,346 | |

| 861 | |

| 820 | |

| 787 | |

| 763 | |

| 672 |

Ghent is home to a large number of people of foreign origin and immigrants. From the 2020 census,[12] it was concluded that 35.5% of the inhabitants have roots outside of Belgium and 15.3% have a non-Belgian nationality. Many neighbourhoods already have a minority-majority population, primarily in the north, east and west of the city, as well as some pockets in the south. Some examples are Brugse Poort, Dampoort, Rabot, Ledeberg, Nieuw Gent/UZ and the area around Sleepstraat (known for its many Turkish restaurants).

Tourism[]

Architecture[]

Much of the city's medieval architecture remains intact and is remarkably well preserved and restored. Its centre is a carfree area. Highlights are the Saint Bavo Cathedral with the Ghent Altarpiece, the belfry, the Gravensteen castle, and the splendid architecture along the old Graslei harbour. Ghent has established a blend between comfort of living and history; it is not a city-museum. The city of Ghent also houses three béguinages and numerous churches including Saint-Jacob's church, Saint-Nicolas' church, Saint Michael's church and St. Stefanus.

In the 19th century Ghent's most famous architect, Louis Roelandt, built the university hall Aula, the opera house and the main courthouse. Highlights of modern architecture are the university buildings (the Boekentoren or Book Tower) by Henry Van de Velde. There are also a few theatres from diverse periods.

The beguinages, as well as the belfry and adjacent cloth hall, were recognized by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites in 1998 and 1999.

The Zebrastraat, a social experiment in which an entirely renovated site unites living, economy and culture, can also be found in Ghent.

Campo Santo is a famous Catholic burial site of the nobility and artists.

One of the more notable pieces of contemporary architecture in Ghent is De Krook, the new central library and media center, a collaboration between local firm Coussée and Goris and Catalan firm RCR Arquitectos.

Museums[]

Important museums in Ghent are the Museum voor Schone Kunsten (Museum of Fine Arts), with paintings by Hieronymus Bosch, Peter Paul Rubens, and many Flemish masters; the SMAK or Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (City Museum for Contemporary Art), with works of the 20th century, including Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol; and the Design Museum Gent with masterpieces of Victor Horta and Le Corbusier. The Huis van Alijn (House of the Alijn family) was originally a beguinage and is now a museum for folk art where theatre and puppet shows for children are presented. The Museum voor Industriële Archeologie en Textiel or MIAT displays the industrial strength of Ghent with recreations of workshops and stores from the 1800s and original spinning and weaving machines that remain from the time when the building was a weaving mill. The Ghent City Museum (Stadsmuseum, abbreviated STAM), is committed to recording and explaining the city's past and its inhabitants, and to preserving the present for future generations.

Restaurants and culinary traditions[]

In Ghent and other regions of East Flanders, bakeries sell a donut-shaped bun called a "mastel" (plural "mastellen"), which is basically a bagel. "Mastellen" are also called "Saint Hubert bread", because on the Saint's feast day, which is 3 November, the bakers bring their batches to the early Mass to be blessed. Traditionally, it was thought that blessed mastellen immunized against rabies.

Other local delicacies are the praline chocolates from local producers such as Leonidas, the cuberdons or 'neuzekes' ('noses'), cone-shaped purple jelly-filled candies, 'babelutten' ('babblers'), hard butterscotch-like candy, and of course, on the more fiery side, the famous 'Tierenteyn', a hot but refined mustard that has some affinity to French 'Dijon' mustard.

Stoverij is a classic Flemish meat stew, preferably made with a generous addition of brown 'Trappist' (strong abbey beer) and served with French fries. 'Waterzooi' is a local stew originally made from freshwater fish caught in the rivers and creeks of Ghent, but nowadays often made with chicken instead of fish. It is usually served nouvelle-cuisine-style, and will be supplemented by a large pot on the side.

The city promotes a meat-free day on Thursdays called Donderdag Veggiedag[14][15] with vegetarian food being promoted in public canteens for civil servants and elected councillors, in all city funded schools, and promotion of vegetarian eating options in town (through the distribution of "veggie street maps"). This campaign is linked to the recognition of the detrimental environmental effects of meat production, which the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization has established to represent nearly one-fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The traditional confectionery is the cuberdon (also known as neuzekes or little noses). These are conical sweets with a soft centre, usually raspberry but other flavours can be found on the many street stalls around the city. Between 2011 and 2015 a feud between two local vendors made international news.[16]

Festivities[]

The city is host to some big cultural events such as the Gentse Feesten, I Love Techno in Flanders Expo, the "10 Days Off" musical festival, the International Film Festival of Ghent (with the World Soundtrack Awards) and the . Also, every five years, an extensive botanical exhibition (Gentse Floraliën) takes place in Flanders Expo in Ghent, attracting numerous visitors to the city.

The Festival of Flanders had its 50th celebration in 2008. In Ghent it opens with the OdeGand City festivities that takes place on the second Saturday of September. Some 50 concerts take place in diverse locations throughout the medieval inner city and some 250 international artists perform. Other major Flemish cities hold similar events, all of which form part of the Festival of Flanders (Antwerp with Laus Polyphoniae; Bruges with MAfestival; Brussels with KlaraFestival; Limburg with Basilica, Mechelen and Brabant with Novecento and Transit).

The city of Ghent will co-host the 2020 World Choir Games together with the city of Antwerp.[17] Organised by the , the World Choir Games is the biggest choral competition and festival in the world.

Nature[]

The numerous parks in the city can also be considered tourist attractions. Most notably, Ghent boasts a nature reserve (Bourgoyen-Ossemeersen, 230 hectare (570 acre)[18]) and a recreation park (Blaarmeersen, 87 hectares; 215 acres).[19]

Economy[]

The port of Ghent, in the north of the city, is the third largest port of Belgium. It is accessed by the Ghent–Terneuzen Canal, which ends near the Dutch port of Terneuzen on the Western Scheldt. The port houses, among others, large companies like ArcelorMittal, Volvo Cars, Volvo Trucks, Volvo Parts, Honda, and Stora Enso.

The Ghent University and a number of research oriented companies, such as Ablynx, Innogenetics, Cropdesign and Bayer Cropscience, are situated in the central and southern part of the city.

As the largest city in East Flanders, Ghent has many hospitals, schools and shopping streets. Flanders Expo, the biggest event hall in Flanders and the second biggest in Belgium, is also located in Ghent. Tourism is becoming a major employer in the local area.[citation needed]

Transport[]

As one of the largest cities in Belgium, Ghent has a highly developed transport system.

Road[]

By car the city is accessible via two motorways:

- The E40 connects Ghent with Bruges and Ostend to the west, and with Brussels, Leuven and Liège to the east.

- The E17 connects Ghent with Sint-Niklaas and Antwerp to the north, and with Kortrijk and Lille to the south.

In addition Ghent also has two ringways:

- The R4 connects the outskirts of Ghent with each other and the surrounding villages, and also leads to the E40 and E17 roads.

- The R40 connects the different downtown quarters with each other and provides access to the main avenues.

Rail[]

The municipality of Ghent comprises five railway stations:

- Gent-Sint-Pieters Station: an international railway station with connections to Bruges, Brussels, Antwerp, Kortrijk, other Belgian towns and Lille. The station also offers a direct connection to Brussels Airport.

- Gent-Dampoort Station: an intercity railway station with connections to Sint-Niklaas, Antwerp, Kortrijk and Eeklo.

- Gentbrugge Station: a regional railway station in between the two main railway stations, Sint-Pieters and Dampoort.

- Wondelgem Station: a regional railway station with connections to Eeklo once an hour.

- Drongen Station: a regional railway station in the village of Drongen with connections to Bruges once an hour.

Public transport[]

Ghent has an extensive network of public transport lines, operated by De Lijn.

Trams[]

- Line 1: Flanders Expo – Sint-Pieters-Station – Korenmarkt (city centre) – Wondelgem – Evergem

- Line 2: Zwijnaarde Bibliotheek – Sint-Pieters-Station – Zonnestraat (city centre) – Brabantdam – Zuid – Melle Leeuw (fuse of line 21 and 22 as of May 2017[20])

- Line 4: UZ – Sint-Pieters-Station – Muide – Korenmarkt (city centre) – Zuid – Moscou

- Line 21: Zwijnaarde Bibliotheek – Sint-Pieters-Station – Zonnestraat (city centre) – Zuid – Melle Leeuw (fused into line 2)

- Line 22: Kouter – Bijlokehof – Sint-Pieters-Station – Zonnestraat (city centre) – Zuid – Gentbrugge (fused into line 2)

Buses[]

- Line 3: Mariakerke – Korenmarkt (city centre) – Dampoort – Gentbrugge (formerly a trolleybus line; see picture below)

- Line 5: Van Beverenplein – Sint-Jacobs (city centre) – Zuid – Heuvelpoort – Nieuw-Gent

- Line 6: Watersportbaan – Zuid – Dampoort – Meulestede – Wondelgem – Mariakerke

- Line 8: AZ Sint-Lucas – Sint-Jacobs (city centre) – Zuid – Heuvelpoort – Arteveldepark

- Line 9: Mariakerke – Malem – Sint-Pieters-Station – Ledeberg – Gentbrugge

- Line 17/18: Drongen – Malem – Korenmarkt (city centre) – Dampoort – Oostakker

- Line 38/39: Blaarmeersen – Ekkergem -Korenmarkt (city centre) – Dampoort – Sint-Amandsberg

Apart from the city buses mentioned above, Ghent also has numerous regional bus lines connecting it to towns and villages across the province of East Flanders. All of these buses stop in at least one of the city's regional bus hubs at either Sint-Pieters Station, Dampoort Station, Zuid or Rabot.

International buses connecting Ghent to other European destinations are usually found at the Dampoort Station. A couple of private bus companies such as Eurolines, Megabus and Flixbus operate from the Dampoort bus hub.

Buses to and from Belgium's second airport – Brussels South Airport Charleroi – are operated by Flibco, and can be found at the rear exit of the Sint-Pieters Station.

Cycling[]

Ghent has the largest designated cyclist area in Europe, with nearly 400 kilometres (250 mi) of cycle paths and more than 700 one-way streets, where bikes are allowed to go against the traffic. It also boasts Belgium's first cycle street, where cars are considered 'guests' and must stay behind cyclists.[citation needed] In 2017 the city restricted car traffic circulation which boosts cycling.[21] More cyclists means a higher demand for bicycle parking stations. In 2010, the plans to renovate Gent-Sint-Pieters railway station, included 10,000 bicycle parking spots.[22] In 2020 several sections of the underground parking facilities have been built, and the targets have been adjusted to a total of 17,000 parking spots.[23]

Sports[]

In the Belgian first football division Ghent is represented by K.A.A. Gent, who became Belgian football champions for the first time in its history in 2015. Another Ghent football club is KRC Gent-Zeehaven, playing in the Belgian fourth division. A football match at the 1920 Summer Olympics was held in Ghent.[24]

The Six Days of Ghent, a six-day track cycling race, is held annually, taking place in the Kuipke velodrome in Ghent. In road cycling, the city hosts the start and finish of the Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, the traditional opening race of the cobbled classics season.[25] It also lends its name to another cobbled classic, Gent–Wevelgem, although the race now starts in the nearby city of Deinze.[26]

The city hosts an annual athletics IAAF event in the Flanders Sports Arena: the Indoor Flanders meeting where two-time Olympic champion Hicham El Guerrouj set an indoor world record of 3:48.45 in the mile run in 1997.[27]

The Flanders Sports Arena was host to the 2015 Davis Cup Final between Belgium and Great Britain.[28]

Notable people[]

- Alexander Agricola, Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance (1445/1446–15 August 1506)

- Leo Baekeland, chemist and inventor of Bakelite (1863–1944)

- Saint Bavo, patron saint of Ghent (589–654)

- Tiesj Benoot, cyclist (born 1994)

- Marthe Boël, feminist (1877–1956)

- Josse Boutmy, composer, organist and harpsichordist (1697–1779)

- Cornelius Canis, composer of the Renaissance, music director for the chapel of Charles V in the 1540s–1550s

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Karel V, Charles Quint (1500–1558)

- Kevin De Bruyne, professional footballer (born 1991)

View of the city of Ghent of 1540, made by Lucas de Heere, a famous Flemish painter.[29]

View of the city of Ghent of 1540, made by Lucas de Heere, a famous Flemish painter.[29] - Willy De Clercq, liberal politician and European Commissioner (1927–2011)

- Caspar de Crayer, painter (1582–1669)

- Pedro de Gante, Franciscan missionary in Mexico (c. 1480 – 1572)

- Frans de Potter, writer, (1834–1904)

- Emma De Vigne, painter (1850–98)

- Charlotte de Witte, DJ and record producer (b. 1992)

- Joseph Guislain, physician (1797–1860)

- Daniel Heinsius, scholar of the Dutch Renaissance (1580–1655)

- Henry of Ghent, scholastic philosopher (c. 1217 – 1293)

- Xavier Henry, shooting guard/small forward for the NBA's Los Angeles Lakers (born 1991)

- Corneille Jean François Heymans, physiologist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1892–1968)

- Victor Horta, Art Nouveau architect (1861–1947)

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (1340–1399)

- Suzanne Lilar, essayist, novelist, and playwright (1901–1992)

- Saint Livinus of Ghent, (580–657)

- Louis XVIII of France was exiled in Ghent during the Hundred Days in 1815

- Pierre Louÿs, poet and romantic writer (1870–1925)

- Maurice Maeterlinck, poet, playwright, essayist, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1862–1949)

- Hippolyte Metdepenningen, lawyer and politician (1799–1881)

- Gerard Mortier, Belgian opera director (b. 1943)

- Gaelle Mys, Olympic gymnast (b. 1991)

- Jacob Obrecht, composer of the Renaissance (c. 1457 – 1505)

- Frans Rens, writer, (1805–1874)

- Gabriel Ríos, musician (b. 1978)

- Jacques Rogge, former president of the IOC (born 1942)

- Charles John Seghers, Jesuit clergyman and missionary (1839–1886)

- Patrick Sercu, Belgian track cyclist (born 1944)

- Soulwax & 2 Many DJs, electronic/rock band headed by David and Stephen Dewaele

- Jacob van Artevelde, statesman and political leader (c. 1290 – 1345)

- Cédric Van Branteghem, athlete (born 1979)

- Gustave Van de Woestijne, painter (1881–1947)

- Karel van de Woestijne, writer (1878–1929)

- Hugo van der Goes, painter (c. 1440 – 1482)

- Jan van Eyck, painter (c. 1385 – 1441)

- Geo Verbanck, sculptor (1881 - 1961)

- Bradley Wiggins, British cyclist (born 1980)

- Jan Frans Willems, writer (1793–1846)

International relations[]

Twin towns – sister cities[]

Ghent is twinned with:[30]

|

Gallery[]

Entrance gate of Oude Vismijn ("Old Fish Market")

The Rabot Gate

Vrijdagmarkt Square with statue of Jacob van Artevelde

City palace Hotel d'Hane-Steenhuyse

Ruins of Saint Bavo's Abbey

See also[]

- List of Mayors of Ghent

References[]

- ^ "Wettelijke Bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2018". Statbel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "Medieval and magical, vibrant and edgy – the Belgian city is a sensory overload". The Guardian. 23 February 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Statistics Belgium; Werkelijke bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2008 (excel-file) Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Population of all municipalities in Belgium, as of 1 January 2008. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

- ^ Statistics Belgium; De Belgische Stadsgewesten 2001 (pdf-file) Archived 29 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Definitions of metropolitan areas in Belgium. The metropolitan area of Ghent is divided into three levels. First, the central agglomeration (agglomeratie) with 278,457 inhabitants (1 January 2008). Adding the closest surroundings (banlieue) gives a total of 455,302. And, including the outer commuter zone (forensenwoonzone) the population is 594,582. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "History of Gent". gent.be. Archived from the original on 18 August 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2006.

- ^ Adrian Room, Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features, and Historic Sites, McFarland, 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Nicholas, David. The Domestic Life of a Medieval City: Women, Children and the Family in Fourteenth Century Ghent. p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ghent over the centuries: Concise history of a stubborn city

- ^ "Climate Summary for Ghent, Belgium". weatherbase.com. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Klimaatstatistieken van de Belgische gemeenten" (PDF) (in Dutch). Royal Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ Nijs, Joram. "OVERZICHT. België telt 1,25 miljoen buitenlanders". Het Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ https://gent.buurtmonitor.be

- ^ "Gand et Flandre : chroniques inédites, avec cartes, miniatures, monuments, armories, scels, et aultres choses historiques & tant curieuses". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Ghent's veggie day: for English speaking visitors" on Vegetarisme.be

- ^ "Belgian city plans 'veggie' days" on BBC News (12 May 2009).

- ^ Van De Poel, Nana (22 July 2017). "A Tale of Two Cuberdon Vendors: The Story Behind Ghent's 'Little Nose War'".

- ^ "Double gold for next host country of the World Choir Games 2020/". INTERKULTUR. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Nature Domain De Bourgoyen | Visit Gent". visitgent.be. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Blaarmeersen Sport and Recreation Park – Sightseeing in Ghent". inyourpocket.com. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ https://static.delijn.be/Images/LCD%20LW%20einde%20Bravoko_tcm3-16462.jpg[permanent dead link]

- ^ Youtube: Streetfilms, 2-1-2020: The Innovative Way Ghent, Belgium Removed Cars From The City

- ^ In Dutch: Project Gent Sint-Pieters, nieuwsbericht 9 november 2016:2000 bijkomende fietsenstallingen

- ^ In Dutch: Project Gent Sint-Pieters: Voorstelling project, Stationsproject: Fiets, site bezocht op 28-1-2020

- ^ FIFA Confederations Cup – Olympic Football Tournament Antwerp 1920 – FIFA.com Archived 1 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Omloop Het Nieuwsblad race guide". Team Sky. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Beaudin, Matthew (23 March 2013). "Storied Ghent-Wevelgem poised for a brutal edition". VeloNews. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "World records". iaaf.org. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Ghent to host 2015 Davis Cup Final". daviscup.com. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Zicht op de stad Gent, de toestand voor 1540 weergevend, gemaakt voor de Proost van Sint-Baafs Viglius ab Aytta in 1564.Gemaakt voor 60 fl. door Lucas d'Heere; hersteld in 1677 door J.B. Herqueau. Zicht genomen van een plaats tussen de Dendermondse en de Antwerpse Poort". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Twin cities". Stad Gent. City of Ghent. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Wiesbaden's international city relations". Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ "European networks and city partnerships". Nottingham City Council. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

Further reading[]

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ghent. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ghent. |

- Official website

(in Dutch)

(in Dutch) - Official Tourist website (in Dutch, English, French, German, and Spanish)

- Flanders Tourism Website (in Dutch, French, German, Spanish, Swedish, Danish, Italian, Czech, Japanese, and Chinese)

- Ghent

- Municipalities of East Flanders

- Port cities and towns in Belgium

- Provincial capitals of Flanders