Kryvyi Rih

Kryvyi Rih

Кривий Ріг | |

|---|---|

| Ukrainian transcription(s) | |

| • National | Kryvyi Rih |

| • ALA-LC | Kryvyĭ Rih |

| • BGN/PCGN | Kryvyy Rih |

| • Scholarly | Kryvyj Rih |

From upper left: Savior Transfiguration Cathedral, ArcelorMittal, Kryvyi Rih Main Station, Maksyma Hor'koho Square, Saksahan boat station | |

Flag  Coat of arms  | |

| Motto(s): Life-long city | |

| Anthem: Anthem of Krivoy Rog | |

Kryvyi Rih Location of Kryvyi Rih in Ukraine | |

| Coordinates: 47°53′48″N 33°22′14″E / 47.8968021°N 33.3705314°ECoordinates: 47°53′48″N 33°22′14″E / 47.8968021°N 33.3705314°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| District | |

| Historic Governorates | Kherson Yekaterinoslav |

| Founded | 1775 (246 years ago) |

| Town charter | 1860 |

| City status | 1919 |

| Administrative HQ | Kryvyi Rih City Hall, Ploshcha (Square) Molodizhna |

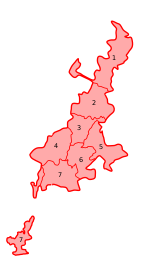

| Raions | List of 7

|

| Government | |

| • Type | City council, regional |

| • Mayor | City council secretary Yuri Vilkul (Mayor died on 15 August 2021, since then his powers are temporarily exercised by the city council secretary)[1] (Vilkul Bloc – Ukrainian Perspective[1]) |

| • Governing body | Kryvyi Rih City Council |

| Area | |

| • City of regional significance | 430 km2 (170 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 84 m (276 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • City of regional significance | |

| • Rank | 7th, UA |

| • Metro | |

| Demonym(s) | Kryvorizhanyn, Kryvorizhanka, Kryvorizhtsi |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 50000-50479 |

| Area code | +380 56(4) |

| Website | krmisto |

Kryvyi Rih (Ukrainian: Криви́й Ріг [krɪˌʋɪj ˈr⁽ʲ⁾iɦ], lit. 'Curved Cape' or 'Crooked Horn')[3] or Krivoy Rog (Russian: Кривой Рог [krʲɪˌvoj ˈrok]) is a city in Central Ukraine; it is the 7th-most populous city in the country.[4] It lies within a large urban area and serves as the administrative center of Kryvyi Rih Raion. It hosts the administration of , one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[5] Population: 612,750 (2021 est.)[6]

Located at the confluence of the Saksahan and Inhulets rivers, Kryvyi Rih has been a major settlement for most of its history. It was founded as a postal station in 1775 by the Cossacks. Developed as a military settlement until 1860, it formed part of Kherson Governorate. It was incorporated during the 20th century with areas of Yekaterinoslav. The settlement began to expand "at an astonishing rate" at the beginning of the 1880s. Kryvyi Rih's urbanization was unplanned and stimulated by mining exploitation. French and English investment contributed to a boom in metallurgy, iron mining, and investigation of rich deposits of iron ore. The was built in 1884 to transport iron ore to the Donbas. This catalyzed the growth of Kryvyi Rih into a major industrial town; it gained city status in 1919.

Nationalization and investment spurred by Soviet authorities led to extensive growth. In 1934 Kryvorizhstal was built, the first of more than 500 factories. Kryvyi Rih National University was founded here. Financially, the city's postwar growth after the Nazi occupation increased after 1965 due to economic reforms. Also, investment spurred by Ukrainian Independence, institution of a market economy led to extensive regeneration, particularly in the city centre.

As of 2016 Kryvyi Rih is arguably the main steel-industry city of Eastern Europe. It is a large, globally important centre of the iron-ore mining and metallurgy region, known as the Kryvbas.

History[]

Etymology[]

The city was founded in the 18th century by Zaporozhian Cossacks. Kryvyi Rih in Ukrainian literally means "Crooked Horn" or "Curved Cape". According to local legend, the city was founded by a "crooked" (Ukrainian slang for one-eyed) Cossack named Rih.[7] But, records pre-dating the founding of the city refer to the area by the same name. It appears based on the shape of the landmass formed by the confluence of the river Saksahan with the Inhulets.

Early history[]

The Inhulets Palanka (an administrative division of the Zaporizhian Sich, a polity of the Cossacks) was established in 1734. A list of villages and winter camps from that time mentions Kryvyi Rih. In 1770[8] the camp of Zaporizhian Sich was founded.[9] Four years later Johann Anton Güldenstädt visited the area and made the first survey and scientific description.

On May 8, 1775, after the end of the Russian-Turkish War, Russian authorities opened a postal station and railway track, linking this settlement to Kremenchuk, Kinburn foreland and Ochakov, all garrisons of the Imperial Russian Army. The station was tended by five Cossacks.

Kryvyi Rih was still a village in the early 1800s.[10] It had three water mills, which made up the largest industry. The first stone houses were built in 1828.[11] The village became a township in 1860.[12]

The tallest building at the end of the 1800s was the Central Synagogue, built by the thriving Jewish community. They worked as artisans, traders and merchants.[12]

Industrial growth[]

Alexander Pol (also known as Paul), a Russian Imperial [13] geologist, discovered and initiated iron ore investigation and production in this area. He is credited with discovering the Kryvbas.[14][15] This stimulated formation of a mining district.[16] In 1874 Alexander II initiated a railway,[17] to run 505 km. This enabled transportation connecting to the nearest factories and greatly sped up the development of the region.

In 1880, with 5 million francs of capital, Paul founded the "French Society of Kryvyi Rih Ores". In 1882 16.4 thousand tons of ore were extracted from surface mines on the outskirts of town by 150 workers. A centre of capitalism, this region was the greatest area of ore extraction in the Russian empire. The first underground mine of the basin began operations in 1886.[18] Metallurgy, a new branch of industry, was founded in 1892, when the first blast furnace of Hdantsivka ironworks was started. The export of ore to Silesia soon began.

Alexander Pol studied iron ore in detail and proved its commercial value

Ore quarry in 1899

Joltaїa Rieka Iron Mining Company share, 1899

Poshtova Street about 1900

Krivoy Rog Mutual Credit Society

Region map in 1914

Minerais de Fer de Krivoї Rog share

Five schools were soon established.[19] An aerial cableway was built in the town. The city's industry attracted new people looking for a quick profit.[20] The supply of mined ore soon exceeded demand. Many mines had to temporarily suspend operations, and others had to reduce their workers and output by more than half. Workers had harsh conditions, lacking social security, or contracts. Environmental conditions in the mines caused them to suffer lung cancer, tuberculosis and asthma. The shutdown caused thousands of people to be out of work. At the same time, workers began to develop ideas about socialism and democracy. The labor unrest resulted in several terrorist attacks and strikes. In 1905 there were also anti-Jewish pogroms and repressions, and younger Jews left the area, many for the United States.[21]

The First World War interrupted access to the export markets, and many workers were drafted into the military. The city survived in 1917. Soviet power was established in January 1918.[22][23]

The Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic,[24] founded on 12 February 1918, became a self-declared republic of the Russian SFSR and sought independence from Ukraine. On 29 March 1918 it became a republic within Ukraine, but was fully occupied by German forces in support of the Central Rada. It was disbanded on 20 March 1918[25] when the independence of Soviet Ukraine was announced.[26]

Around this time, Kryvyi Rih's status was changed from township to city. It was founded by Uyezd as part of the Yekaterinoslav Governorate. It included 30 volosts. In late 1919, it was briefly ruled by the Volunteer Army.[22]

Soviet era[]

On January 17, 1920 the Red Army finally took Kryvyi Rih. The city's population totaled 22,571. The city did not have a drinking water system until 1924, when a 55.3 km (34.4 mi) system was laid underground. Foreign investments were stopped, and the mine operations were revived. The first Mining Institute opened in 1929. The Medical and Pedagogical Institutes were founded.[27] In 1931 the foundation of the metallurgical works was laid.[28] The first blast furnace of the metallurgical works produced steel three years later. The city grew rapidly. In 2002 it had 160 industrial enterprises and 947 shops.[29]

Nazi occupation[]

During World War II, Kryvyi Rih was occupied by the German Army as part of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine from August 15, 1941 to February 22, 1944. From 20 September 1941 to August 1944, the Government, factories, and Kryvyi Rih Institute were evacuated to Nizhny Tagil.

Germans immediately began to build up local government, installing executives, gendarmerie and police forces. The Ukrainian national liberation movement in Krivoy Rog was organized by marching groups OUN. The Nazis conducted ethnic cleansing of mostly Jewish residents, in a large-scale holocaust. On October 13, 1941 the Nazis executed 700 people.[30] From October 1941 to April 1942, the Nazis killed 6293 persons, in August 1943 – 13 people.[29] A total of 5,000 Jews were murdered, and 800 POWs from a nearby camp. Thousands of Jews had fled the area to the east before the Germans reached the city.

Hitler had repeatedly stressed the crucial importance of this area "The Nikopol manganese is of such importance, it cannot be expressed in words. Loss of Nikopol (on the Dnieper River, southwest of Zaporozhye) would mean the end of war."[31] The German bridgehead on the left bank of the Dnieper gave the German command a base in order to restore the land connection with their forces locked in the Crimea.[32] During the first half of January,[33] Soviet troops made repeated attempts to eliminate the Nikopol-Krivoy Rog enemy group, but because of the stubborn resistance of German troops, did not achieve success. The fleeing German Army almost totally destroyed Kryvyi Rih during the Nikopol–Krivoy Rog Offensive.

AEG power station built in 1930

Wehrmacht soldiers operating 10.5 cm leFH 18. Svobody Street, 1942

Soldiers arresting people, 1942

Miners and pioneers pose in front of the Banner of Krivoi Rog. 1952.

Dimitrova Street, like many in the city center, is lined with dozens of Stalinist buildings

City Hall was built in the year of the city's 200th jubilee.

Nativity of the Theotokos Church, 1886, restored in the 2000s[34]

Post-Second World War and Post-Soviet[]

After the war, people lived among the ruins while rebuilding the housing stock. The housing shortage was met by innovative technological solutions, and temporary barracks and houses were quickly built. The two chief kinds of cheap new materials[clarification needed] were used later for years afterward.

In the late 1940s, initiatives such as Stakhanovite movement stimulated redevelopment:[35] Khrushchyovkas, new mines, shoe and wool spinning-factories, the Central Iron Ore Enrichment Works, Northern Iron Ore Enrichment Works, and building the City Circus. Trolleybuses in Kryvyi Rih were launched in 1957,[36]

Kryvyi Rih Airport became International. By 1990 Kryvbas produced 42% of USSR and 80% of Ukrainian ore.[37]

Since the late 20th century, large sections of the city dating from the 1960s have been either demolished and re-developed or modernised with the use of beton and steel.[38] Old flats have been converted into modern apartments. Nine microdistricts of 17 and 9-floor panelák apartments have since been developed.

The Kryvyi Rih TV Mast is a 185m-tall, guyed tubular steel mast, built in 1960. It carries three crossbars on two levels, which run from the mast structure to the guys. All three crossbars are equipped with gangways that carry additional smaller antennas.[39]

The city was rebuilt with broad avenues lined by wide sidewalks. Tram lines run down the center of the major streets. The sidewalks have been lined with several rows of urban trees, such as lindens and horse chestnuts. Many people live in the 5- to 9-story apartment buildings that are built around large inner courtyards. Many courtyards have also been planted with trees, giving the impression that the city is within a park.

Ukraine's declaration of independence in 1991 has been followed by radical changes in every sphere of city life .[40] In the 1990s the city was known for crime (mostly organized gangs from neighbourhood's raiding other neighbourhood's[41]),[42] but robberies have been suppressed. Investment followed the 2005 privatization of Kryvorizhstal by ArcelorMittal, and was aided further by Metinvest.[43]

Kryvyi Rih's city centre has undergone extensive redevelopment.[44] The city has one of the biggest flower clocks in Europe.[45] New and renovated complexes such as Auchan and The Union have become popular shopping and entertainment destinations. Kryvyi Rih is ranked as among the 30[46] most comfortable cities for living in Ukraine.

Until 18 July 2020, Kryvyi Rih was incorporated as a city of oblast significance and the center of Kryvyi Rih Municipality. It also served as the administrative center of Kryvyi Rih Raion though it did not belong to the raion. The municipality was abolished as administrative division in July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast to seven. The area of Kryvyi Rih Municipality was merged into the Kryvyi Rih Raion.[47][48]

Government[]

|

|

The City of Kryvyi Rih is governed by the Kryvyi Rih City Council. it is a city municipality that is designated as a separate district within its oblast.

Administratively, the city is divided into "raions" ("districts"). Presently, there are 7 raions: Dzerzhinskiy, Central City, Terny, Saksahan, Ingulets, Zhovtnevy and Dovhuntsevsky. Small townships, Avanhard, Horniatske, Ternovaty Kut, Kolomoitsevo and Nowoivanovka were added to the City.[49]

Originally Ingulets povit of Novorossiysk Governorate was established on lands of Ingulets palanca in 1775 after the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich. In 1775/1776 it was part of Kherson Governorate. In 1783, the povit centre became Kryvyi Rih, and it was renamed to Kryvyi Rih povit. In 1860 Kryvyi Rih got the status of township in Kherson Governorate. In 1919 township was granted city status in Yekaterinoslav Governorate and, later, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. As a result of the administrative reform in 1923 Kryvyi Rih povit converted to Kryvyi Rih okruga, which in 1930 became an independent administrative unit of Ukraine.[50][51]

Kryvyi Rih has three single-mandate parliamentary constituencies entirely within the city, through which members of parliament (MPs) are elected to represent the city in Ukraine's national parliament. At the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election, they were won by Petro Poroshenko Bloc and independent candidates with representation being from Yuri Pavlov, Andriy Halchenko, respectively.[52] In multimember districts city voted for Opposition Bloc, union of all political forces that did not endorse Euromaidan. At the 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary election all local MPs were representing Servant of the People, the party of Ukrainian President and Kryvyi Rih native Volodymyr Zelensky.[53][54][55]

In the last decades, Kryvyi Rih has generally supported candidates belonging to the Party of Regions and (in the 1990s) Communist Party of Ukraine in national and local elections. Same situation was with presidential elections, strong support had Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yanukovych. After 2014 events of Euromaidan, mass demonstrations and clashes in central city,[56] Party of Regions lost its influence, and Kryvyi Rih supported Petro Poroshenko.

Culture[]

Kryvyi Rih has a thriving theatre, circus and dance scene, and is home to a number of large performance venues. The first theater was the Coliseum, built in 1908. The New Theatre of Vyzenberh and Hrushevskyy followed in 1911, at the corner of Lenina and Kalynychenko streets. Kryvbas Theatre began its activities in 1931, and three years later was incorporated with the Shevchenko Theater. There are also the Doll Theatre and Movement Theatre.

Kryvyi Rih is noted as the birthplace Eugenie Gershoy. She emigrated to the United States with her family in 1903, and there became an American sculptor and watercolorist. Gershoy's work is in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her papers are held at Syracuse University.[58] Indie band Brunettes Shoot Blondes, folk musician Eduard Drach, actress Helena Makowska, and dancer Vladimir Malakhov also originated in the city.

The first film screenings were conducted in the city in the early 1920s. In 1934 Lenin Cinema was built. Today there are three movie theaters: Olympus, Odessa and Multiplex.[59] The Kryvyi Rih Circus feature large-scale exhibition space where fairs are held.[60] Soviet heritage are Palaces of Culture in every district of the city.

The local historical museum celebrates Cossack history, the industrial heritage of the area and its role in the Soviet State. The municipally owned Art Gallery houses a collection of local painting.[61]

The nightlife of the city has expanded significantly since the 2000s. Big clubs such as Hollywood[62] and Sky, have attracted touring djs, pop and rap performers. Another major scene of the city is the Palace of Youth and Students of the Kryvyi Rih National University (KNU).[63] The most popular fast-food, McDonald's, is located at 95th Block.

Ukrainian cuisine is found adjacent to a range of Jewish and popular American foods: bagels, cheesecake, hot dogs, shawarma and pizza. Japanese cuisine and other Asian restaurants, hookahs, sandwich joints, trattorias and coffeehouses have become ubiquitous. Other well-known places – City Pub and Prado Cafe. The city is home to the annual electronic music festival.[64] Rock band music, a tradition in Ukraine, is an important part city's life and is hosted in few small pubs.

Landmarks[]

Kryvyi Rih's buildings display a variety of architectural styles, ranging from eclecticism to contemporary architecture. The widespread use of red brick and block apartments characterize the city. Much of the architecture in the city was built during its prosperous days as a center for the ore trade. Just outside the immediate city center is a large number of former factories. Some have been totally destroyed; others are in desperate need of restoration.

Stalinist architecture was the predominant style of postwar apartments, of 5 to 7 stories. City Hall is the best example of The decree On liquidation of excesses.[65] Khrushchyovka is a type of low-cost, concrete-paneled or brick three- to five-storied apartment building which was developed in the USSR during the early 1960s. It was named after Nikita Khrushchev, then premier of the Soviet government. Dozens of these aging buildings around the city are now past their design lifetime. There are six microdistricts.

The city has many Christian churches, the most notable being the Savior Transfiguration Cathedral of the Ukrainian Orthodox church. It is the base of the Kryvyi Rih Eparchy, which was established on July 27, 1996.[66] Roman Catholic chapel located in old town. Pokrova church, Mykhailivska church and Christmas church were destroyed in the 1930s during the Great Purge, never to be used as a church again.[67]

In Kryvyi Rih, the Jewish community built a new, large synagogue, that opened in 2010.[68][69]

Large parks hold many of Kryvyi Rih's public monuments. There are numerous socialist realism-style monuments installed in the Soviet years to honor Cossacks, Olexander Paul, Taras Shevchenko (2), Bohdan Khmelnytsky (3, since 1954), , Alexander Pushkin, Fyodor Sergeyev, Mikhail Lermontov, and Maxim Gorky. The few Lenin monuments were destroyed during euromaidan events in 2014.[70] Dozens of cenotaphs and memorials to Second World War soldiers were erected. A Sukhoi Su-15 is on display near Aviator Club, Yakovlev Yak-40 at National Aviation University, Vyzvolennia Square hold IS3 tank. Russian locomotive class Ye placed near Railway station.

Kryvyi Rih Botanical Gardens of NAS

Shevchenko Theatre

Central Art Square

Pushkin park in snow

Kryvyi Rih has few[71] designated natural monuments: the old pear near Karnavatka, another pear of 1789,[72] Vizyrka landscape reserve, Northern and Southern Red Beam, Amphibolite, Arkose and Skelevatski Outputs, Mopr Rocks, Slate rocks, Sandstone rock.[73] Park named after the newspaper Pravda is very famous by its ampir boat station.[74] Kryvyi Rih Botanical Gardens of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NAS) was established in 1980.[75]

Education[]

Major Kryvyi Rih National University was originally formed as college and Mining Institute in 1929. It gained university status in 1982. Kryvyi Rih Pedagogical Institute it was founded in 1930 as an Institute of Vocational Training, is the oldest pedagogical institution in Kryvyi Rih, reorganized in Pedagogical Institute. In 2011 Cabinet of Ukraine founded Kryvyi Rih National University by uniting Mining Institute, Pedagogical University, Economic Institute of Kyiv National Economic University and Department of the National Metallurgical Academy of Ukraine.

Other institutions are local Department of Dnepropetrovsk State University of Internal Affairs, campuses of Zaporizhzhya National University, National University Odesa Law Academy and Interregional Academy of Personnel Management, college of National Aviation University.

In 2014 Donetsk Tugan-Baranovsky National University of Economics and Trade was evacuated to Kryvyi Rih after a long War in Donbass. Its future is uncertain.[76]

According to Frances Cairncross (in April 2010) "There are too many small universities, the majority of which are ineffectively governed and mired in corruption. They are not able to withstand existing global challenges."[77] According to Anders Åslund (in October 2012) the quality of doctoral education is bad, particularly in management training, economics, law and languages.[78] He also signaled that the greatest problem in the Ukrainian education system is corruption.[78]

There are 149 general secondary schools and 150 nursery schools and kindergartens in Kryvyi Rih.[79] Additionally, there are evening schools for adults, musical, art, sports and specialist technical schools.

Sport[]

FC Hirnyk Kryvyi Rih is a football club based in Hirnyk Stadium, and currently competes in the Ukrainian First League. It is part of the Sports Club Hirnyk which combines several other sections. The club's owner is the Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Combine (KZRK), the biggest subterranean mining public company in Ukraine.

Kryvyi Rih was also home to another football team, Kryvbas Kryvyi Rih. The team was founded as FC Kryvyi Rih in 1959. The next year it was part of the republican sports society Avanhard. After a couple of years, it changed to Hirnyk, before obtaining current its name in 1966. Kryvbas debuted in the Ukrainian Premier League in the 1992–93 season. They had been in the top league since their debut, with their best finish in third place in the 1998–99 and 1999–2000 seasons. At the end of the 2012–13 season the team finished in 7th place, however, due to financial difficulties the club declared itself bankrupt in June 2013. FC Kryvbas-2 Kryvyi Rih was the reserve team of Kryvbas. In 1998 the club entered into the professional leagues to compete in the Second League. In 3 seasons the club moved to the Amateur Level before competing one last time in Second League.

SC Kryvbas is a professional basketball club. Achievements of the team are winning the Ukrainian Basketball League in 2009 and winning the Higher League in 2003 and 2004. Since 2010 the team is active in the Ukrainian Basketball SuperLeague.

The city is famous for its annual autorally. It was also the birthplace of the Ukrainian tennis players Valeria Bondarenko, Alona Bondarenko and Kateryna Bondarenko.

Geography[]

At 47°55′0″N 33°15′0″E / 47.91667°N 33.25000°E, 415 kilometres (260 mi) south of Kyiv, the city extends for 126 km from north to south,[80][81] paralleling the ore deposits. The city centre is on the east bank of the Inhulets River, near its confluences with the River Saksahan. Kryvyi Rih's geographic features were highly influential in its early development industrial city.

The city is set in the rolling steppe land surrounded by fields of sunflowers and grain. A short distance east of the city center, there is an area along a small lake where glacial boulders were deposited. As a result, this area was never cultivated and contains one of the few remaining patches of wild steppe vegetation in the area. The city's environmental and construction safety is a growing problem due to abandoned mines and polluted ore-processing waste. According to the Scientific Hygienic Centre of Ukraine, the city is one of the most unfavorable places to live because of these problems.[82]

Climate[]

Kryvyi Rih experiences a dry warm continental climate (Dfa) according to the Köppen climate classification system, like much of southern Ukraine. This tends to generate warm summers and cold winters with relatively low precipitation. Snowfalls are not common in the city, due to the urban warming effect. However,[83] districts that surround the city receive more snow and roads leading out of the city can be closed[84] due to snow.

| hideClimate data for Kryvyi Rih (1981–2010, extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

38.6 (101.5) |

39.6 (103.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.1 (−24.0) |

−27.3 (−17.1) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.4 (1.24) |

29.9 (1.18) |

29.7 (1.17) |

35.3 (1.39) |

44.9 (1.77) |

63.6 (2.50) |

56.4 (2.22) |

40.7 (1.60) |

43.6 (1.72) |

35.7 (1.41) |

34.6 (1.36) |

34.4 (1.35) |

480.2 (18.91) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 125 |

| Average snowy days | 14 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 4 | 12 | 51 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.8 | 84.2 | 79.0 | 66.0 | 62.0 | 66.8 | 64.0 | 61.4 | 67.8 | 76.2 | 86.2 | 87.9 | 74.0 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[85] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization[86] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

| National communities | |

|---|---|

| Russian | |

| Armenian | |

| Moldovan | |

| Polish | |

| Jewish | |

| Romani | |

| Georgian | |

|

Historically the population of Kryvyi Rih began to increase rapidly during the Interwar period, peaking at 197 000 in 1939.[87] From then the population began to decrease rapidly. Foreign workers arrived, and there was increased building of social housing estates by the Kryvyi Rih City Council after the Second World War, such as Sotshorod and Sonyachny.[88]

The 2014 estimate for the population of Kryvyi Rih was 654,900 (8th in Ukraine). This was a decrease of 4 348 since the 2013 estimate. Since 2001, the population has grown by 48 001. In 2013, deaths exceeded births by 3589. Net migration rate is 234 (negative).[87][89]

According to the UNHCR and City Council, 7000 people of Donetsk and Luhansk have fled to Kryvyi Rih since the beginning of 2014 War in Donbass, not including those who did not register as asylum seekers.[90][91][92][93][94][95]

Kryvyi Rih historically had a Christian majority-population. It has numerous churches, particularly in the central city. The well-known Savior Transfiguration Cathedral in Saksahan Raion is Orthodox administrative center, bishop of the Kryvyi Rih Eparchy has his main residence here. The town has a school of icon painting. The patron saint of the city is Saint Nicholas, as well as bishops Onufry and Porphyry.[96]

This was long a centre of Jewish population. Its Central Synagogue was the tallest building in town in the late 19th century. The majority of region's Jews live here, and a significant Jewish community has been re-established. Beis Shtern Shtulman Synagogue[97] opened in 2010 in the Central City. In the early twentieth century, the city had two synagogues, located on Kaunas street. As part of Roman Catholic Diocese of Kharkiv-Zaporizhia, the city has the Kostel of Mary Mother of Jesus. Kryvyi Rih is also home to Evangelical Christians, CEF, and Vedas communities.

In terms of ethnic composition, there are no official statistics. Jews have made up the single largest ethnic minority.[98] Today they number 15 000, followed by Russians[citation needed], and Armenians.

Large immigrant groups include people from Korea, Poland, Moldova, Assyrians and Azerbaijan, and Roms.[99] Numerous African students come to the city to attend local universities.[100] Central city and Dovhuntsevskyi Raion are centres of population for ethnic minorities.

The Kryvyi Rih Metropolitan Region has a population over 1 010 000 in 2010. In addition to Kryvyi Rih, the KMR (factically) includes far more than five raions, numberous territories in central and southern parts of Ukraine. The KMR is the sixth-largest within Ukraine.

Economy[]

In 2020 Kryvyi Rih's share in Ukraine's national GDP was estimated to be about 6%.[101] In mid-2014 Kryvyi Rih had an IPI of ₴41.6bn[79][102] (about $3bn[103]) with 17.9% growth which is 41.8% of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast IPI. Export reached $2.520m (4.9% decrease), Import - $276m. City got $4.899m of foreign Investmentments, mainly from Germany, Cyprus, Netherlands, and the UK.

Official unemployment throughout 2014 averaged 0.63%. Average wage is ₴4.022 ($266,[103] 19.4% more than average Ukraine).[79][102]

Processing and mining industry - the two largest sectors of Kryvyi Rih. Rest fraction is about 50%. City has over 53[104] plants, mines and factories. ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih, owned by ArcelorMittal since 2005 is the largest private company by revenue in Ukraine,[105] producing over 7 million tonnes of crude steel, and mined over 17 million tonnes of iron ore. As of 2011, the company employed about 37 000 people. 4 Iron Ore Enrichment Works of Metinvest are a large contributors to the UA's balance of payments. Another giants of city are Evraz mining company and HeidelbergCement.[79][102]

The largest amount of emission of air pollutants in Ukraine is generated in Kryvyi Rih.[101]

Transport[]

Local public transportation in Kryvyi Rih includes the Metrotram (subway), buses[79][102] and minibuses line, trolleybuses (in operation since 1957, the system presently comprises 23 routes), trams (one of the world's largest tram networks, operating on 105.8 kilometres of total route. As of 2014, it was composed of 13 lines) and, taxi.

The publicly owned and operated Kryvyi Rih Metrotram is the fastest, the most convenient and affordable network that covers most, but not all, of the city. The Metrotram is continuously expanding towards the city limits to meet growing demand, currently has two lines with a total length of 18.7 kilometres (11.6 miles) and 11 stations. Despite its designation as a "metro tram" and its use of tram cars as rolling stock, the Kryvyi Rih Metrotram is a complete rapid transit system with enclosed stations and tracks separated both from roads and from the city's conventional tram lines. City public transport serviced 66m persons in the first part of 2014.[79][102]

Kryvyi Rih Metrotram at Zarichna station

Prospekt Metalurhiv station of the Kryvyi Rih Metrotram was Opened in 1989

Commuter rail train at the Kryvyi Rih Main Station. The city's railroads have a long history.

On 1 May 2021 Kryvyi Rih became the first city in Ukraine to introduce free travel in public transport for its citizens.[106] In order not to pay for municipal transport one must show a special electronic "Kryvyi Rih Card".[106]

The historic tram system,[36] once a well maintained and widely used method of transport, is now gradually being phased out in favor of buses and trolleybuses.

The city has no cycling lines. The taxi market is expansive but not regulated. In particular, the taxi fare per kilometer is not regulated. There is a fierce competition between private taxi companies.

Kryvyi Rih International Airport is the airport that serves the city. It is located 17.5 km (10.9 Miles) northwest of the city of Kryvyi Rih.

Twin towns – sister cities[]

Kryvyi Rih is twinned with:[107]

Rustavi, Georgia

Rustavi, Georgia Zhodzina, Belarus

Zhodzina, Belarus

Friendly cities[]

Košice, Slovakia

Košice, Slovakia Lublin, Poland

Lublin, Poland Miskolc, Hungary

Miskolc, Hungary

See also[]

- List of people from Kryvyi Rih

References[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in Ukrainian) Ex-mayor of Kryvyi Rih Vilkul will rule the city again, Ukrayinska Pravda (25 August 2021)

- ^ "Kryvyi Rih (Ternopil Oblast, Kryvyi Rih Raion)". weather.in.ua. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ Oxford Dictionaries. "Kryvyi Rih". Oxford University Press, 2013. Accessed 27 August 2013.

- ^ "UA population estimates". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ^ "Криворожская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- ^ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "Комаров В.О. Iсторiя Криворiжжя Днепропетровск: Сiч, 1992". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ "Історична хроніка подій 1734-1900. Олександр О.Мельник, ведучий науковий співробітник Криворізького історико-краєзнавчого музею". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ^ В. Ізмайлов. Подорож у полуденну Росію в 1799 р. у листах, виданих Володимиром Ізмайловим

- ^ Перелік (Списку) казенних селищ Херсонського й Олександрійського повітів, які у 1816 - 1817 р.р. були звернені у військові поселення

- ^ «По Катерининській залізниці», вип. 1-й, Katerinoslaw, 1903 р

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary 1890—1907

- ^ Milward, Alan; Saul, S. B. (6 August 2012). The Development of the Economies of Continental Europe 1850-1914 (Routledge Revivals). ISBN 9781136810886.

- ^ Sudrussland Mageteisen und Sisenglantztatten

- ^ Рубін П.Криворожский бассейн и его железные руды. Горный журнал, 1888 г., т. 1

- ^ Конткевич С. Геологічний опис околиць Кривого Рогу, Херсонської губернії

- ^ Записки капитан-лейтенанта Семечкина», Вид. Об-ва горных инженеров, 1900 р

- ^ "Початок добутку залізної руди. Індустріальний розвиток (1881 – 1899)". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Діловий і комерційний Кривий Ріг. 1914 р

- ^ Гірничо-заводський листок №4, 1902р

- ^ "Історична хроніка подій (м. Кривий Ріг) 1900-1903". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Історична хроніка подій (м. Кривий Ріг) 1900-1903". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Снегирёв В. В. Между двух огней. Предыстория создания ДКР // «Молодогвардеец» — Луганск, 6−11.10.1990.

- ^ Материалы о Донецко-Криворожской Республике. Сост. и предисл. Х. Мышкис // «Літопис Революції»: Журнал Істпарту ЦК КП(б)У — 1928. — № 3(30).

- ^ Гамрецький Ю. М. ІІ обласний з"їзд Рад Робітничих і Солдатських Депутатів Донбасу і Криворіжжя // Питання історії СРСР, № 22. — Харків, 1977.

- ^ Лихолат А. В. Здійснення ленінської національної політики на Україні — Київ, 1967. — С.156−161.

- ^ "Історія КНУ". knu.edu.ua. Archived from the original on 2015-03-22.

- ^ "Our History. ArcelorMittal". arcelormittal.com.ua.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Історична хроніка подій 1917 - 2002". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ "Marmer Jewish Museum". jewish-museum-marmer.dp.ua.

- ^ История Второй мировой войны. 1939—1945. / Коллектив авторов. — Т. 8. — М.: Воениздат, 1977.

- ^ Типпельскирх К. История Второй мировой войны. — СПб.: Полигон; М.:АСТ, 1999.

- ^ Грылев А. Н. Днепр — Карпаты — Крым. — М.: Наука, 1970.

- ^ Божко А. А. Храм Рождества Пресвятой Богородицы (1886—2012): Исторический очерк / Алексей Алексеевич Божко. — Кривой Рог, 2012. — 84 с., ил.

- ^ Українська радянська енциклопедія. В 12-ти томах / За ред. М. Бажана. — 2-ге вид. — К.: Гол. редакція УРЕ, 1974-1985.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Електротранспорт України: Енциклопедичний путівник / Сергій Тархов, Кость Козлов, Ааре Оландер. — Київ: Сидоренко В. Б., 2010. — 912 с.: іл., схеми. — ISBN 978-966-2321-11-1.

- ^ "Our History. ArcelorMittal". arcelormittal.com.ua.

- ^ Осуществленные строительством основные объекты архитектора Иосифа Каракиса // Архитектор Иосиф Каракис: Судьба и творчество (Альбом-каталог к столетию со дня рождения) / Под ред. Бабушкин С. В., Бражник Д., Каракис И. И., А. Пучков; Сост. Д. Бражник, И. Каракис, И. Несмиянова. — Киев, 2002. — С. 97. — 102 с. — (Н0(4УКР)6-8). — ISBN 966-95095-8-0.

- ^ "Криворожская телевышка". 1kr ua.

- ^ "Our History. ArcelorMittal". arcelormittal.com.ua.

- ^ President’s hometown, The Ukrainian Week (27 January 2020)

- ^ ""Бегуны". История глупой войны". kri.com.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-12-19.

- ^ "Реконструкция". KRLife.

- ^ "Проспект Маркса". KRLife.

- ^ "Криворожские цветочные часы попали в Книгу рекордов". Rambler News. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ "Фокус определил 50 лучших городов для жизни в Украине". focus.ua. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13.

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 2020-07-18. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

- ^ "Виконком міської ради". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ^ Волости и важнѣйшія селенія Европейской Россіи. По данным обслѣдованія, произведеннаго статистическими учрежденіями Министерства Внутренних Дѣл, по порученію Статистическаго Совѣта. Изданіе Центральнаго Статистическаго Комитета. Выпуск VIII. Губерніи Новороссійской группы. СанктПетербургъ. 1886. — VI + 157 с.

- ^ Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года. М.: Издание ЦСУ Союза ССР, 1928-29. Том 10-16. Таблица VI. Население по полу, народности

- ^ "СПИСОК народних депутатів України, обраних на позачергових виборах народних депутатів України 26 жовтня 2014 року". «Голос України». — № 218 (5968). — 2014. — 12 листопада. — С. 4–9. Archived from the original on 2014-11-27.

- ^ 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary election Results. Ukrayinska Pravda

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (24 April 2019). "Ukraine's Newly Elected President Is Jewish. So Is Its Prime Minister. Not All Jews There Are Pleased". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "CEC registers Zelensky, Smeshko, Bohoslovka, thus raising number of presidential contenders in Ukraine to 26". Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Криворожский Евромайдан". 0664. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ "World's biggest floral clock begins to tick off time in Ukraine's Kryvyi Rih". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Eugenie Gershoy Papers: An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Киноафиша". Киноафиша.

- ^ "Kryvyi Rih Circus". Kryvyi Rih Circus.

- ^ "Local Museum". 1KR UA.

- ^ "Hollywood city VK". Hollywood city VK.

- ^ "KNU students Club". KNU.

- ^ "Turbofly VK". Turbofly VK.

- ^ Architecture of The Stalin Era, by Alexei Tarkhanov (Collaborator), Sergei Kavtaradze (Collaborator), Mikhail Anikst (Designer), 1992, ISBN 978-0-8478-1473-2

- ^ "» Епархия". Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Православные храмы - История Кривого Рога - 1775.dp.ua". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Светлана, Поддубная. "Главная страница". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "В Кривом Роге открыли одну из крупнейших синагог в Восточной Европе". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Vandals continue demolition of monuments to Vladimir Lenin in Ukraine". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Кафедра інформатики та прикладної математики - Тематика курсових, магістерських робіт". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Енциклопедія Криворіжжя. — У 2-х т./Упоряд. В. П. Бухтіяров. — Кр. Ріг: «ЯВВА», 2005

- ^ "Природні заповідники, заказники, парки та пам'ятки природи Дніпропетровської області". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Парк им. газеты "Правда"". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Криворізький ботанічний сад НАН України". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Из Донецкой и Луганской областей эвакуированы уже девять университетов". ZN UA.

- ^ Education problems deeper than language, Kyiv Post (2 April 2010)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Outdated educational system translates into lagging economy, Kyiv Post (4 October 2012)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Бюлетень "Кривий Ріг у цифрах і фактах 2013 р." (PDF). Kryvyi Rih City Council. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ^ Dnepropetrovsk Oblast 1:200,000 map, Ukraine 2004 and 2005.

- ^ The following website claims that: "Currently, the city of Krivoy Rog has an area of 430.0 km2 (166.0 sq mi), and extends 126 km (78.29 mi) from north to south (the largest in Europe) and is 20 km (12.43 mi) in width." ("В настоящий момент город Кривой Рог занимает территорию площадью 430,0 км2 и имеет протяжность с севера на юг 126 км (наибольшая в Европе) и ширину до 20 км.:) Официальный сайт исполсома города Кривщгщ Рого Archived 2011-04-25 at the Wayback Machine (ru) (ua) Archived 2011-03-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Библиотечный каталог авторефератов Украины, Scientific Hygienic Centre of Ukraine.

- ^ "Кривой Рог встретил снегопад во всеоружии?". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ новостей, Независимое бюро. "Независимое бюро новостей - Из-за сильных снегопадов заблокировано движение в четырех областях Украины". Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Климат Кривого Рога [Climate of Kryvyi Rih] (in Russian). Pogoda.ru.net. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Демографічний прогноз міста Кривого Рогу. Кривий Ріг". Kryvyi Rih City Council. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ^ "Історична хроніка подій (м. Кривий Ріг)". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ^ "Демоситуацiя". Kryvyi Rih City Council. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02.

- ^ "More Than a Million Ukrainians Have Been Displaced, U.N. Says". The New York Times. 2 September 2014.

- ^ "ООН: Домівки через бойові дії в Україні полишили понад 415 тисяч людей". Deutsche Welle. August 20, 2014.

- ^ "UNHCR: 730,000 flee Ukraine for Russia". Deutsche Welle. August 20, 2014.

- ^ "В Кривой Рог опять массово кинулись беженцы с востока". krlife.com.ua.

- ^ "На Дніпропетровщині будуть створені бізнес-центри для переселенців". krlife.com.ua.

- ^ "Сколько переселенцев с восточных областей в Кривом Роге?". comments.ua. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ "Мост Днепр". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ "Еврейская община Кривого Рога". Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Міські осередки громадських організацій та об'єднань". kryvyirih.dp.ua. Archived from the original on 2015-09-27.

- ^ "Фестиваль национально-культурных сообществ в Кривом Роге". 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "KNU International". KNU.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in Ukrainian) "Green" curtain and metallurgical candidate, The Ukrainian Week (28 September 2020)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Економічний прогноз. Кривий Ріг". Kryvyi Rih City Council. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "XE: UAH / USD Currency Chart. Ukrainian Hryvnia to US Dollar Rates". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Промышленно-производственные предприятия - Кривой Рог". Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Top Ukrainian Companies By Revenue

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in Ukrainian) Free, but unpleasant. In Kryvyi Rih, the fare in transport, which needs urgent modernization, is being abolished, The Ukrainian Week (21 April 2021)

- ^ "Міжнародна співпраця". kr.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Kryvyi Rih. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

Bibliography[]

- Криворожье. Справочник-путеводитель / Днепропетровск: Днепропетровское книжное издательство, 1963. — 162 с. (in Russian)

- Кривому Рогу — 200. Историко-экономический очерк / Редколлегия: П. Л. Варгатюк и др. — Днепропетровск: «Промінь», 1975. — 208 с. (in Russian)

- Новик Л. И. Кривой Рог: Путеводитель-справочник / Л. И. Новик, Д. И. Кан. — Днепропетровск: «Промiнь», 1986. — 191 с., цв. ил. (in Russian)

- Пахомов А. Г., Борьба трудящихся Криворожья за власть Советов / А. Г. Пахомов. — Днепропетровск: Днепропетровское областное издательство, 1958. — 204 с. (in Russian)

- Альбом Кривой Рог-Гданцевка. 1899. (in German)

- Кривой Рог: Фотоальбом. — Киев: «Мистецтво», 1971. — 137 с., цв. ил. (in Ukrainian)

- Кривий Ріг: Фотоальбом. — Киев: «Мистецтво», 1976. — 146 с., цв. ил. (in Ukrainian)

- Кривий Ріг: Фотоальбом. — Киев: «Мистецтво», 1983. — 143 с., цв. ил. (in Ukrainian)

- Кривий Ріг: Фотоальбом. — Киев: «Мистецтво», 1989. — 144 с., цв. ил. (in Ukrainian)

- Кривий Ріг — моє місто / Тамара Трофанова. — Кривий Ріг: Видавничий дім, 2009. — [36] с.: фотогр. — 3500 (1 завод-1000) экз. — ISBN 978-966-177-038-5. (in Ukrainian)

- Кривий Ріг: фотоальбом / редкол.: Г. П. Гончарук (ред.) и др.; фотогр. А. Соловьёв. — Д.: АРТ-ПРЕСС, 2010. — 152 с.: фотогр. — на укр. и англ. языках. — 2200 экз. — ISBN 978-966-348-227-9. Посвящён 235-летию Кривого Рога. (in Ukrainian)

- Рукавицын И. А. Привет из Кривого Рога / И. А. Рукавицын. — К.: Арт-Технология, 2014. — 104 с.: ил. (русский язык)

- Визначні місця України / Київ: Держполітвидав УРСР, 1961. — 787 с. (in Ukrainian)

- Криворожский горнорудный институт. К 50-летию института / Коллектив авторов. — Издательство Львовского университета, 1972. — 184 с. (in Russian)

- Грушевой К. С. Тогда, в сорок первом… / К. С. Грушевой. — Москва, 1972. — 78 с. (in Russian)

- Мельник О. О., Криворіжжя: від визволення до перемоги. Хроніка подій з 22 лютого 1944 до 9 травня 1945 р / О. О. Мельник. — Кривий Ріг: Видавничий дім, 2004. — 56 с. (in Ukrainian)

- Советская историческая энциклопедия / Москва: «Советская энциклопедия», 1965. — Том 8, С. 150–151. (in Russian)

- Украинская советская энциклопедия. Том 5 (in Ukrainian), — С. 499–500. (in Russian)

- История Городов и Сёл Украинской ССР (в 26 томах). Том Днепропетровская область, — С. 285–323. (in Russian)

- Фокин Е. И. Хроника рядового разведчика. Фронтовая разведка в годы Великой Отечественной войны. 1943—1945 гг. / Е. И. Фокин. — М.: ЗАО «Центрполиграф», 2006. — 285 с. — (На линии фронта. Правда о войне). Тираж 6 000 экз. ISBN 5-9524-2338-8. (in Russian)

- Географический энциклопедический словарь. Географические названия. Издание второе, дополненное / Гл. ред. А. Ф. Трёшников. — Москва: «Советская энциклопедия», 1989. (in Russian)

External links[]

- Kryvyi Rih administration website (in Ukrainian and English)

- Kryvyi Rih at Curlie

- 1kr City News (in Russian)

- Google Maps Satellite Image of Kryvyi Rih

- Testing the mettle of Ukraine's steel city from the BBC World News

- The murder of the Jews of Kryvyi Rih during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.

- Kryvyi Rih

- Cities in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

- Populated places established in the 18th century

- 1775 establishments in Europe

- Cities of regional significance in Ukraine

- Populated places established in the Russian Empire

- 18th-century establishments in Ukraine

- Khersonsky Uyezd