List of artificial objects leaving the Solar System

Below is a list of artificial objects leaving the Solar System. All of these objects are space probes and the upper stages of their launch vehicles, and all were launched by NASA.

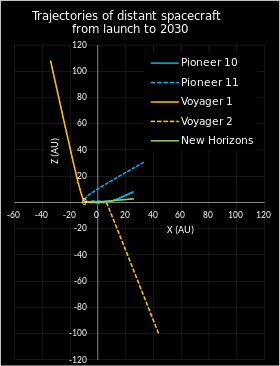

Of the major spacecraft, Voyager 1, Voyager 2, and New Horizons are still functioning and are regularly contacted by radio communication, while Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 are now derelict. In addition to these spacecraft, some upper stages and de-spin weights are leaving the Solar System, assuming they continue on their trajectories.

These objects are leaving the Solar System because their velocity and direction are taking them away from the Sun, and at their distance from the Sun, its gravitational pull is not sufficient to pull these objects back or into orbit. They are not impervious to the gravitational pull of the Sun and are being slowed, but are still traveling in excess of escape velocity to leave the Solar System and coast into interstellar space.

Planetary exploration probes[]

- Pioneer 10 – launched in 1972, flew past Jupiter in 1973 and is heading in the direction of Aldebaran (65 light years away) in the constellation of Taurus. Contact was lost in January 2003, and it is estimated to have passed 120 astronomical units (AU; one AU is roughly the average distance between Earth and the Sun: 150 million kilometers (93 million miles)).[1]

- Pioneer 11 – launched in 1973, flew past Jupiter in 1974 and Saturn in 1979. Contact was lost in November 1995, and it is estimated to be at around 100 AU.[2] The spacecraft is headed toward the constellation of Aquila, northwest of the constellation of Sagittarius. Barring an incident, Pioneer 11 will pass near one of the stars in the constellation in about 4 million years.[3]

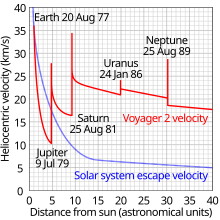

- Voyager 2 – launched in August 1977, flew past Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1981, Uranus in 1986, and Neptune in 1989. The probe left the heliosphere for interstellar space at 119 AU on 5 November 2018.[4] Voyager 2 is still active. It is not headed toward any particular star, although in roughly 40,000 years it should pass 1.7 light-years from the star Ross 248.[5] If undisturbed for 296,000 years, it should pass by the star Sirius at a distance of 4.3 light-years.

- Voyager 1 – launched in September 1977, flew past Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980, making a special close approach to Saturn's moon Titan. The probe passed the heliopause at 121 AU on 25 August 2012 to enter interstellar space.[6] Voyager 1 is still active. It is headed towards an encounter with star Gliese 445 (AC +79 3888), which lies 17.6 light-years from Earth, in about 40,000 years.[7]

- New Horizons – launched in 2006, the probe flew past Jupiter in 2007 and Pluto on 14 July 2015. It flew past the Kuiper belt object 486958 Arrokoth on January 1, 2019, as part of the Kuiper Belt Extended Mission (KEM).[8]

Although other probes were launched first, Voyager 1 has achieved a higher speed and overtaken all others. Voyager 1 overtook Voyager 2 a few months after launch, on 19 December 1977.[9] It overtook Pioneer 11 in 1983,[10] and then Pioneer 10—becoming the probe farthest from Earth—on February 17, 1998.[11]

Depending on how the "Pioneer anomaly" affects it, New Horizons will also probably pass the Pioneer probes, but will need many years to do so. It will not overtake Pioneer 11 until the 22nd century, will not overtake Pioneer 10 until the end of that century, and will never overtake the Voyagers.[10]

Speed and distance from the Sun[]

To put the distances below in context, Pluto's average distance (semi-major axis) is about 40 AU.

| Name | Launched | Distance (AU)[12][13] |

Speed (km/s)[12][13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voyager 1 | 1977 | 155.4 | 16.9 |

| Pioneer 10 | 1972 | 130.4 | 11.9 |

| Voyager 2 | 1977 | 129.3 | 15.3 |

| Pioneer 11 | 1973 | 108.6 | 11.1 |

| New Horizons | 2006 | 52.4[14] | 13.8 |

Data above as at 15 Feb 2022. Source: JPL[12] and heavens-above.com[13].

Solar escape velocity is a function of distance (r) from the Sun's center, given by

where the product G Msun is the heliocentric gravitational parameter. The initial speed required to escape the Sun from its surface is 618 km/s (1,380,000 mph),[15] and drops down to 42.1 km/s (94,000 mph) at Earth's distance from the Sun (1 AU), and 4.21 km/s (9,400 mph) at a distance of 100 AU.[16][17]

Voyager 1 and 2 speed and distance from the Sun

Pioneer 10 and 11 speed and distance from the Sun

New Horizons speed and distance from the Sun.

In order to leave the Solar System, the probe needs to reach the local escape velocity. After leaving Earth, the Sun's escape velocity is 42.1 km/s. In order to reach this speed, it is highly advantageous to also use the orbital speed of the Earth around the Sun, which is 29.78 km/s. By later passing near a planet, a probe can gain extra speed with a gravity assist.

Propulsion stages[]

Every planetary probe was placed into its escape trajectory by a multistage rocket, the last stage of which ends up on nearly the same trajectory as the probe it launched. Because these stages cannot be actively guided, their trajectories are now different from the probes they launched (the probes were guided with small thrusters that allow course changes). However, in cases where the spacecraft acquired escape velocity because of a gravity assist, the stages may not have a similar course and there is the extremely remote possibility that they collided with something. The stages on an escape trajectory are:

- Pioneer 10 third stage, a TE364-4 variant of the Star-37 solid fuel rocket.[18]

- Voyager 1 fourth stage, a Star 37E solid fuel rocket.[19]

- Voyager 2 fourth stage, a Star 37E solid fuel rocket.[19]

- New Horizons third stage, a Star 48B solid fuel rocket, is on a similar escape trajectory out of the Solar System to New Horizons, even arriving at Jupiter six hours before New Horizons. On October 15, 2015 it passed Pluto's orbit at a distance of 213 million kilometers (over 1 AU) distant from Pluto.[20][21] This was four months after New Horizons' Pluto flyby.[22]

In addition, two small yo-yo de-spin weights on wires were used to reduce the spin of the New Horizons probe prior to its release from the third-stage rocket. Once the spin rate was lowered, these masses and the wires were released, and so are also on an escape trajectory out of the Solar System.[23][24]

None of the above objects are trackable - they have no power or radio antennae, spin uncontrollably, and are too small to be detected. Their exact positions are unknowable beyond their projected Solar System escape trajectories.

The third stage of Pioneer 11 is thought to be in solar orbit because its encounter with Jupiter would not have resulted in escape from the Solar System.[19][better source needed] Pioneer 11 gained the required velocity to escape the Solar System in its subsequent encounter with Saturn.[dubious ]

On January 19, 2006 the New Horizons spacecraft to Pluto was launched directly into a solar-escape trajectory at 16.26 kilometers per second (58,536 km/h; 36,373 mph) from Cape Canaveral using an Atlas V and the Common Core Booster, Centaur upper stage, and Star 48B third stage.[25] New Horizons passed the Moon's orbit in just nine hours.[26][27] The subsequent encounter with Jupiter only increased its velocity, and just enabled the probe to arrive at Pluto three years earlier than without this encounter.

Thus the only objects to date to be launched directly into a solar escape trajectory were the New Horizons spacecraft, its third stage, and the two de-spin masses. The New Horizons Centaur (second) stage is not escaping; it is in a 2.83-year heliocentric (solar) orbit.[20]

The Pioneer 10 and 11, and Voyager 1 and 2 Centaur (second) stages are also in heliocentric orbits.[24][28]

Future[]

Given the huge emptiness of interstellar space, all the objects listed here are likely to continue into deep space in timelines that, barring the exceptionally unlikely chance of their colliding with (or being collected by) another object, could outlast even the mainstage existence of the Sun's life, billions of years hence. They do not, however, have enough velocity to escape the Milky Way galaxy into intergalactic space.

Ulysses[]

In 1990, Ulysses was launched and was designed to study the Sun; its extended mission ended in 2008. Ulysses is currently in a 79° inclination orbit around the Sun with the periapsis crossing the orbit of Jupiter. In November 2098, it will have another close fly-by with Jupiter, crossing between the orbits of Europa and Ganymede. After this slingshot maneuver, it will possibly enter a hyperbolic trajectory around the Sun and eventually leave the Solar System.[29]

Ulysses is now switched-off as its RTG power supply has run down, and so is uncontactable and cannot be tracked or guided in any way. Its exact trajectory is therefore unknowable as factors such as solar radiation pressure could significantly alter its encounter path.

Interstellar Express[]

Interstellar Express or Interstellar Heliosphere Probe is the current name for a proposed Chinese National Space Administration program designed to explore the heliosphere and interstellar space.[30] The program will feature two space probes that will be launched in 2024 and follow differing trajectories to encounter Jupiter to assist them out of the Solar System. The first probe, IHP-1, will travel toward the nose of the heliosphere, while the second probe, IHP-2, will fly near to the tail, skimming by Neptune and Triton in January 2038.[31][32] There may be another probe—tentatively IHP-3—which would launch in 2030 to explore to the northern half of the heliosphere.[33][34] Thus IHP-1 and IHP-2 will also be leaving the Solar System, as well as the first non-NASA probes to achieve this status.

Gallery[]

Photograph of Voyager 1 / Voyager 2

Artist's concept of Pioneer 10 / Pioneer 11

Artist's concept of Pioneer 10 near Jupiter

Artist's concept of New Horizons approaching Pluto.

Artist's concept of New Horizons near Pluto.

See also[]

- Interstellar probe

- Intergalactic travel

- List of artificial objects in heliocentric orbit

- List of artificial objects on extraterrestrial surfaces

- Deliberate crash landings on extraterrestrial bodies

- Oberth effect

References[]

- ^ "Pioneer 10 Live Position and Data". TheSkyLive.com. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ "Pioneer 11 Live Position and Data". TheSkyLive.com. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ "The Pioneer Missions". NASA. 3 March 2015.

- ^ Gill, Victoria (December 10, 2018). "Nasa's Voyager 2 probe 'leaves the Solar System'". BBC News. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Voyager – Mission �� Interstellar Mission". NASA. June 22, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Harwood, William (September 12, 2013). "Voyager 1 finally crosses into interstellar space". CBS News.

- ^ Wall, Mike (13 September 2015). "Interstellar Traveler: NASA's Voyager 1 Probe On 40,000-Year Trek to Distant Star". Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne (2016-07-01). "New Horizons Receives Mission Extension to Kuiper Belt, Dawn to Remain at Ceres" (Press release). Washington, DC. NASA. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris; Goldader, Jeff (20 August 2011). "Thirty-four years after launch, Voyager 2 continues to explore". nasaspaceflight.com. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ a b Cranor, David (4 December 2017). "When the Voyagers passed the Pioneers". Nothing More Powerful. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Voyager - The Interstellar Mission". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA.

- ^ a b c "Voyager – Mission Status". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Spacecraft escaping the Solar System". Heavens Above. Chris Peat. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (2021-04-15). "NASA's New Horizons Reaches a Rare Space Milestone". NASA. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ "What is escape velocity?". www.qrg.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ^ "WolframAlpha: solar escape velocity at 100 AU".

- ^ "WikiHow: How to Calculate Escape Velocity". Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- ^ "NASA - NASA Glenn Pioneer Launch History". NASA.

- ^ a b c "rockets - Where are the upper stages for the Voyager/Pioneer stages? - Space Exploration Stack Exchange". stackexchange.com.

- ^ a b Stern, Alan; Guo, Yanping (October 28, 2010). "Where Is the New Horizons Centaur Stage?". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

- ^ "Star 48b Third-stage Motor - Unmanned Spaceflight.com". unmannedspaceflight.com.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (26 January 2006). "Derelict Booster to Beat Pluto Probe to Jupiter". Space.com. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Pierre Bauduin. "New Horizons". weebau.com.

- ^ a b "Deep space probes and other manmade objects beyond near Earth space". johnstonsarchive.net.

- ^ Scharf, Caleb A. (February 25, 2013). "The Fastest Spacecraft Ever?". Scientific American. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ Neufeld, Michael (July 10, 2015). "First Mission to Pluto: The Difficult Birth of New Horizons". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "New Horizons: Mission Overview" (PDF). International Launch Services. January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ https://usspaceobjectsregistry.state.gov/Lists/SpaceObjects/DispFormaspx?ID=3348.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Solar orbiter Ulysses ends mission after 18 years". Reuters. July 2009.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (16 April 2021). "China to launch a pair of spacecraft towards the edge of the solar system". SpaceNews. SpaceNews. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Wang, Chi; Li, Hui; Guo, Xiaocheng; Xu, Xinfeng (2021-01-27). "太阳系边际探测项目的科学问题". 深空探测学报(中英文) (in Chinese). 7 (6): 517–524. doi:10.15982/j.issn.2096-9287.2020.20200058. ISSN 2096-9287. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (November 19, 2019). "China Considers Voyager-like Mission to Interstellar Space". Planetary.org. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Wu, Weiren; Yu, Dengyun; Huang, Jiangchuan; Zong, Qiugang; Wang, Chi; Yu, Guobin; He, Rongwei; Wang, Qian; Kang, Yan; Meng, Linzhi; Wu, Ke; He, Jiansen; Li, Hui (2019-01-09). "Exploring the solar system boundary". SCIENTIA SINICA Informationis. 49 (1): 1. doi:10.1360/N112018-00273. ISSN 2095-9486.

- ^ Song, Jianlan. ""Interstellar Express": A Possible Successor of Voyagers". InFocus. Chinese Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

External links[]

- Lists of Solar System objects

- Spacecraft escaping the Solar System

- Lists of artificial objects sent into space