Oppdal

Oppdal kommune | |

|---|---|

Oppdal as seen from the in August 2008 | |

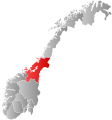

Coat of arms  Trøndelag within Norway | |

Oppdal within Trøndelag | |

| Coordinates: 62°34′25″N 09°36′32″E / 62.57361°N 9.60889°ECoordinates: 62°34′25″N 09°36′32″E / 62.57361°N 9.60889°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Trøndelag |

| District | Dovre Region |

| Established | 1 Jan 1838 |

| Administrative centre | Oppdal |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2019) | Geir Arild Espnes (Sp) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,274.12 km2 (878.04 sq mi) |

| • Land | 2,201.45 km2 (849.98 sq mi) |

| • Water | 72.67 km2 (28.06 sq mi) 3.2% |

| Area rank | 24 in Norway |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 7,001 |

| • Rank | 141 in Norway |

| • Density | 3.2/km2 (8/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | 6% |

| Demonym(s) | oppdaling[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-5021 |

| Official language form | Neutral[2] |

| Website | oppdal |

![]() Oppdal (help·info) is a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. It is part of the Dovre region and the traditional district of Orkdalen. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Oppdal. Other villages in the municipality include Lønset, Vognillan, Fagerhaug, and Holan. The Oppdal Airport, Fagerhaug is located in the northeastern part of the municipality.

Oppdal (help·info) is a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. It is part of the Dovre region and the traditional district of Orkdalen. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Oppdal. Other villages in the municipality include Lønset, Vognillan, Fagerhaug, and Holan. The Oppdal Airport, Fagerhaug is located in the northeastern part of the municipality.

The 2,274-square-kilometre (878 sq mi) municipality is the 24th largest by area out of the 356 municipalities in Norway. Oppdal is the 141st most populous municipality in Norway with a population of 7,001. The municipality's population density is 3.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (8.3/sq mi) and its population has increased by 6% over the previous 10-year period.[3][4]

General information[]

The prestegjeld of Oppdal was established as a municipality on 1 January 1838 (see formannskapsdistrikt). The municipal boundaries have not changed since that time.[5] On 1 January 2018, the municipality switched from the old Sør-Trøndelag county to the new Trøndelag county.

Name[]

The municipality (originally the parish) is named after the old Oppdal farm, since that is where the historic Oppdal Church was located. The Old Norse form of the name was Uppdalr. The first element is upp which means "upper" and the last element is dalr which means "valley" or "dale". Historically, the name was also spelled Opdal.[6]

Coat of arms[]

The coat of arms was granted on 19 February 1982. The blue and white arms represent a junction, since Oppdal is a major centre of commerce and transportation. Three important roads going to Trondheim, Dombås, and Sunndalsøra cross here, and historically the area was used for gatherings, because of this fact.[7]

Churches[]

The Church of Norway has three parishes (sokn) within the municipality of Oppdal. It is part of the Gauldal prosti (deanery) in the Diocese of Nidaros.

| Parish (sokn) | Church Name | Location of the Church | Year Built |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fagerhaug | Fagerhaug Chapel | Fagerhaug | 1921 |

| Lønset | Lønset Chapel | Lønset | 1863 |

| Oppdal | Oppdal Church | Oppdal | 1651 |

| St. Mikael's Chapel | south of Holan | 2012 |

History[]

Oppdal is an alpine community which dates back to the Norwegian Iron Age. It is located at a crossroads for traffic from Trondheim, the Dovrefjell mountain range, and Sunndal on the west coast. This is reflected in the three rays in the coat-of-arms.

Oppdal was first settled sometime before 600 CE. By then there were about 50 farms in the area, and this number grew by about 20 more in the Viking Era. There are remnants of over 700 Pagan grave mounds from the time at Vang, in which jewelry and other pieces from the British Isles were found. This indicates that the area was relatively affluent and participated in the Viking trade. Much of the affluence was likely derived from the availability of game, both in the area and from nearby mountain ranges. Several game traps can still be seen in mountains around Oppdal, particularly ditches for reindeer. There have been more than 80 finds of at least two different types of arrowheads in the area.[8]

Archeological finds in Oppdal indicate that there were less pronounced economic disparities than elsewhere in Norway. Communal efforts to hold off famine and share burdens appear to have been common throughout several centuries.

During the Christian era, Pagan shrines and grave mounds were replaced by churches and chapels. Five rural churches were built in Oppdal at the time, in Vang, Ålbu, Lønset, Lo, and Nordskogen. The Oppdal Church, built to replace an earlier stave church in 1653, stands to this day.[9]

Oppdal was a stop for pilgrims on their way to the St. Olav shrine at the Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim during the Middle Ages. As a result of the heavy stream of pilgrims who followed the Pilgrim's Route prior to the Reformation, King Eystein erected mountain stations where the pilgrims could find food and shelter. Kongsvoll, located on the Driva River along the route where pilgrims passed from the Gudbrandsdal valley into Oppdal was one of these stations, and is still an inn today. Drivstua, further north, was another.[9][10]

Oppdal was particularly affected by the Black Plague, which led to the abandonment of a number of farms. With a worsening of the climate, the community hadn't recovered 170 years later, and there were only 35 farms and 350 people left. Only one church at Vang was still in use. As late as 1742, people in Oppdal died of hunger.

In the early 17th century, Oppdal's fortunes turned and population grew. By 1665, 2,200 people lived in Oppdal, and a new church was built at Vang, the Oppdal Church, which stands to this day. The Lønset Chapel and Fagerhaug Chapel have been re-established, and Oppdal houses several other religious communities. Since the 18th century, the inhabitants of Oppdal have made significant investments in education, leading to the establishment of several small rural schools and, recently, a high school.

In the 19th century, increased fertility and reduced mortality led to population growth that could not be sustained by agricultural resources. Many became tenant farmers, and eventually a large proportion of people from Oppdal emigrated to the United States. The population decreased until 1910, when the railroad from Oslo to Trondheim via Dovre (the Dovre Line) created employment and opened the area for tourism. In 1952, the first ski lift opened, and with further expansions Oppdal now offers one of Norway's largest downhill networks.

In 2013, NRK said that a Labour Party politician was fighting against the establishment of a refugee center.[11]

Government[]

All municipalities in Norway, including Oppdal, are responsible for primary education (through 10th grade), outpatient health services, senior citizen services, unemployment and other social services, zoning, economic development, and municipal roads. The municipality is governed by a municipal council of elected representatives, which in turn elect a mayor.[12] The municipality falls under the Sør-Trøndelag District Court and the Frostating Court of Appeal.

Municipal council[]

The municipal council (Kommunestyre) of Oppdal is made up of 25 representatives that are elected to four year terms. The party breakdown of the council is as follows:

| Party Name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 4 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 2 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 3 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 10 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 1 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 25 | |

Mayor[]

The mayors of Oppdal (incomplete list):

- 2019-present: Geir Arild Espnes (Sp)

- 2015-2019: Kirsti Welander (Ap)

- 2003-2015: Ola Røtvei (Ap)

- 1994-2003: John Egil Holden (Sp)

- 1992-1993: Ola Arne Aune (Sp)

- 1988-1992: Ola Røtvei (Ap)

Geography[]

Oppdal is bordered by two municipalities in Trøndelag county (Rennebu to the northeast and Rindal to the west), two municipalities in Møre og Romsdal county (Surnadal to the north and Sunndal to the west), two municipalities in Hedmark county (Tynset to the east and Folldal to the south), and one municipality in Oppland county (Dovre to the south).

European route E6 passes straight through the commercial center of Oppdal going north and south, and Norwegian National Road 70 connects Oppdal to Kristiansund in the west.[9]

The southeastern part of Trollheimen mountain range is located in the municipality. The municipality covers an area equal to the entire county of Vestfold. The administrative centre is at 545 metres (1,788 ft) above sea level. In 2001, its drinking water was named the best in Norway.[31]

Most of Oppdal's area is mountainous, with large areas above the treeline. At an elevation of 1,985 metres (6,512 ft), Storskrymten is the highest mountain in the county. Other mountains include Blåhøa and Allmannberget. The Speilsalen tunnel was a glacial formation near Blåhøa.

In the valleys there are creeks and rivers which are surrounded by spruce and pine woods; closer to the treeline, birches dominate. There are several lakes in the municipality, the most famous being Gjevilvatnet, a particularly scenic lake with hiking and cross-country skiing trails around it. The lake Fundin is located in the southern part of the municipality.

Heather and alpine meadows provide grazing for sheep in the summer. About 1,161 square kilometres (448 sq mi) of the mountains has been held since time immemorial as a collective (almenning) by farmers in the area, giving them the right to hunt, fish, and rent cabins.

Climate[]

Oppdal has a boreal climate, with spring as the driest season and summer as the wettest season. The climate is slightly continental with an average annual precipitation of only 600 millimetres (24 in). Considering the inland location and the altitude of 600 m above sea level, the winters are fairly mild. The all-time high 30.1 °C (86.2 °F) was recorded July 26, 2019. The all-time low −26.1 °C (−15.0 °F) is from February 2010. The weather station Oppdal-Sæther (604 m) started recording December 1999. The earlier weather station Oppdal-Bjørke (625 m) recorded from 1975 to August 1992. Data for precipitation days is from Oppdal-Mjøen (512 m), which averaged just 470 mm annually in 1961-90. Snakes have never made it to Oppdal, and snowy weather is not that unusual on the 17 May National Day celebrations.

| hideClimate data for Oppdal 1991-2020 (604 m, avg high/low 2004-2020, precip days 1961-90, extremes 1975-2020 incl earlier station) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1 (30) |

0 (32) |

2 (36) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

8 (46) |

3 (37) |

0 (32) |

8 (46) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13 (55) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0 (32) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

3.7 (38.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−6 (21) |

−5 (23) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

8 (46) |

6 (43) |

1 (34) |

−2 (28) |

−5 (23) |

1 (33) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.8 (−14.4) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−21.8 (−7.2) |

−15 (5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−15 (5) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.8 (2.28) |

51.4 (2.02) |

45.3 (1.78) |

30.7 (1.21) |

29.1 (1.15) |

55.2 (2.17) |

78 (3.1) |

85 (3.3) |

45.2 (1.78) |

42.1 (1.66) |

47 (1.9) |

48.7 (1.92) |

615.5 (24.27) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 87 |

| Source 1: yr.no and eklima/Norwegian Meteorological Institute[32] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: weatheronline climate robot (avg high/low) [33] | |||||||||||||

Economy[]

The main industries in Oppdal today are agriculture, tourism, and some light manufacturing. It has the largest sheep population of any municipality in Norway, with 45,000 head of sheep put out to graze in the mountains every year. It is one of Norway's best ski resorts and is surrounded by national parks. A slate quarry exists.[34]

Notable residents[]

- Inge Krokann (1893 in Oppdal – 1962) a writer, his use of the Oppdal dialect makes the area central to his work

- Olav Dalgard(1898–1980) an art historian, filmmaker, author and educator, raised at Oppdal [35]

- Einar Ingvald Haugen (1906–1994) was a Norwegian-American linguist, author and professor at University of Wisconsin–Madison; he was born in Sioux City, Iowa, to Norwegians from Oppdal.

- Sivert Donali (1931 in Oppdal – 2010) a Norwegian sculptor

- Harald Sæther (born 1946 in Oppdal) a Norwegian composer, lives in Oppdal

- Kåre Jostein Simonsen (born 1948 in Oppdal) a Norwegian bandoneon player

- Sjur Loen (born 1958 in Oppdal) a curler, multiple world champion medallist

- Ingebrigt Håker Flaten (born 1971 in Oppdal) a bassist active in the jazz and free jazz genres

- Bård Bjorndalseter, a local woodcarver lives and works in Oppdal

- Twins Silje Øyre Slind & Astrid Øyre Slind (born 1988 in Oppdal) Norwegian cross-country skiers

- Markus Høiberg (born 1991 in Oppdal) a curler, competed at the 2014 Winter Olympics

References[]

- ^ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ Statistisk sentralbyrå (2020). "Table: 06913: Population 1 January and population changes during the calendar year (M)" (in Norwegian).

- ^ Statistisk sentralbyrå (2020). "09280: Area of land and fresh water (km²) (M)" (in Norwegian).

- ^ Jukvam, Dag (1999). "Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Statistisk sentralbyrå.

- ^ Rygh, Oluf (1901). Norske gaardnavne: Søndre Trondhjems amt (in Norwegian) (14 ed.). Kristiania, Norge: W. C. Fabritius & sønners bogtrikkeri. p. 178.

- ^ "Civic heraldry of Norway - Norske Kommunevåpen". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Haugland, Kjell (2002). Oppdals historie – Hovudlinjer og tidsbilde. Oppdal historielag. ISBN 82-7083-269-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Welle-Strand, Erling (1996). Adventure Roads in Norway. Nortrabooks. ISBN 82-90103-71-9.

- ^ Stagg, Frank Noel (1953). The Heart of Norway. George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

- ^ Ap-politiker: – Asylmottak kan føre til knivstikking

- ^ Hansen, Tore, ed. (12 May 2016). "kommunestyre". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Tall for Norge: Kommunestyrevalg 2019 - Trøndelag". Valg Direktoratet. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Table: 04813: Members of the local councils, by party/electoral list at the Municipal Council election (M)" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway.

- ^ "Tall for Norge: Kommunestyrevalg 2011 - Sør-Trøndelag". Valg Direktoratet. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1995" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1996. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1991" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1993. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1987" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1988. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1983" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1984. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1979" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1979. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1975" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1977. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1972" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1973. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1967" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1967. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1963" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1964. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1959" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1960. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1955" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1957. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1951" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1952. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1947" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1948. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1945" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1947. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1937" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1938. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Kommunefakta" (in Norwegian). Oppdal kommune.

- ^ {{cite web |title=yr.no/met.no|url=https://www.yr.no/en/statistics/table/5-63705/Norway/Tr%C3%B8ndelag/Oppdal/Oppdal

- ^ {{cite web |title=Weatheronline|url=https://www.weatheronline.co.uk/weather/maps/city?LANG=en&PLZ=_____&PLZN=_____&WMO=01245&CONT=euro&R=0&LEVEL=162®ION=0004&LAND=NO&MOD=tab&ART=TMX&NOREGION=1&FMM=1&FYY=2004&LMM=12&LYY=2020

- ^ Oppdals gull. Skifer fra Oppdal bekler hytta til Zlatan Ibrahimović, Formel 1-profilen David Coulthard og museer, hoteller og butikker verden over.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 26 August 2020

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oppdal. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Trøndelag. |

- Municipal fact sheet from Statistics Norway (in Norwegian)

- Oppdal travel guide from Visit Oppdal (in Norwegian)

- Oppdal weather and snow report (in Norwegian)

- Oppdal

- Municipalities of Trøndelag

- Ski areas and resorts in Norway

- 1838 establishments in Norway