Al-Qabu

al-Qabu

القبو Qabu, Kabu | |

|---|---|

The mosque for Shaykh Ahmad al-Umari | |

| Etymology: "the vault, or cellar"[1] | |

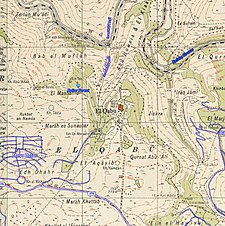

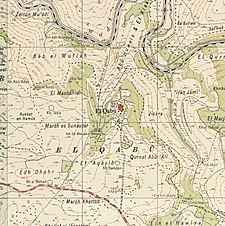

A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Qabu (click the buttons) | |

al-Qabu Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°43′40″N 35°07′10″E / 31.72778°N 35.11944°ECoordinates: 31°43′40″N 35°07′10″E / 31.72778°N 35.11944°E | |

| Palestine grid | 161/126 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Date of depopulation | 22–23 October 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,806 dunams (3.806 km2 or 1.470 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 260[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Mevo Beitar |

Al-Qabu (Arabic: القبو, "the vault, or cellar"),[1] was a Palestinian Arab village in the Jerusalem Subdistrict. The name is an Arabic variation of the site's original Roman name, and the ruins of a church there are thought to date to the era of Byzantine or Crusader rule over Palestine.

Al-Qabu was depopulated on 22–23 October 1948, following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[5][6] Following Israel's establishment, homes in the village were blown up by Israeli troops in May 1949 and in 1950, the moshav of Mevo Beitar was founded on the village lands.

Location[]

Situated on a hilltop that sloped downward steeply on three sides, to the south lay a secondary road that linked al-Qabu to the highway between Bayt Jibrin and Jerusalem which lay at a distance of about 1.5 kilometers (0.93 mi).[7]

History[]

During the period of Roman rule over Palestine, the place was known as Qobi or Qobia.[8] The village had a spring, and was located at the tenth milestone on the road constructed between Bayt Jibrin and Jerusalem under emperor Hadrian.[8][9] The Arabic name of the Palestinian village, al-Qabu, was a modification of the earlier Roman name.[7]

A ruined church by the village was visited by a team from the Survey of Western Palestine in 1873, and they determined that it appeared to date to the period of the Crusades,[10] while other researchers, such as Reverend Dom M. Gisler, OSB in 1939,[9] have determined that it dates to the Byzantine era.[11]

Ottoman era[]

In 1838, in the Ottoman era, it was noted as a Muslim village in the District of el-'Arkub; Southwest of Jerusalem.[12] Edward Robinson further noted that the village was located "among steep rocky mountains".[13]

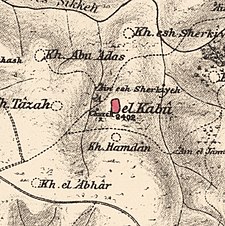

In 1856 the village was named el Kabu on the map of Southern Palestine that Heinrich Kiepert published that year.[14]

In 1863 Victor Guérin described the village, "perched like an eagle's nest", and surrounded by gardens.[15] An Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that kabu had a population of 28, in 18 houses, though the population count included men, only.[16][17]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described the village as being of moderate size, situated on a high hill, with houses built of stone. Other features mentioned were the presence of a ruined church on the hillside, southwest of the village, and two springs in the valley to the west.[18]

The village was laid out in a rectangular plan, extending in a north-south direction along the secondary road. The houses in the village were built primarily of stone. A few small shops in the village were located around its main square. Al-Qabu also had a shrine dedicated to one Shaykh Amad al-'Umari that stood southeast of the village site.[5]

British Mandate era[]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Qabu had a population 139, all Muslims,[19] increasing in the 1931 census to 192, still all Muslim; in a total of 31 houses.[20]

Several springs around the village, including Ayn Tuz and Ayn al-Bayada, provided water for its residents.[21] The Ain esh Sherkiyeh, meaning "The eastern spring", also lay close by.[22]

In the 1945 statistics, Al-Qabu had a population of 260, all Muslims,[2] with a total of 3,806 dunams of land.[3] In 1944-45 the villagers had allocated a total of 1,233 dunums of village land to the cultivation of cereals; 436 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards. Olive trees covered 30 dunams of land,[21][23] while 12 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[24]

1948 and the aftermath[]

The village apparently changed hands several times in the 1948-1949 period,[21] Morris writes that the village was first depopulated on 22–23 October 1948.[4] However, in March 1949 the IDF mounted a series of major attacks eastwards, in the area of al-Qabu. The aim was to gain more territory, drive concentrations of Arabs eastwards, and create facts on the ground before a scheduled UN survey of Israeli and Jordanian positions.[25] Notwithstanding these orders, the Israeli UN liaison officers were at pains to describe to the UN observers that the military clashes were the result of Arab incursions and attacks.[26] In reality, Israeli troops were given direct orders to take al-Qabu, Khirbet Sanasin, al Jab'a, and Khirbet al-Hamam, even if it meant battling Jordanian troops.[27]

Over the course of their operations, Israeli troops from the Fourth Brigade took several hilltops, and went on to clear the area of Arabs. The force, which was armed with machine-guns and mortars, were ordered to "hit every [adult male] Arab spotted in the area [but] not to harm women and children".[28]

After signing the 1949 Armistice Agreements with Jordan on 3 April, a question arose about the villagers of Al-Qabu and al-Walaja, whose inhabitants had gradually returned. These two villages were in Israeli territory under the Armistice Agreement, and Israel wanted them empty. On 1 May 1949, Israeli troops raided the villagers and blew up the houses. IDF reports that the villagers fled.[6]

In 1950, the moshav of Mevo Beitar was established on land that had belonged to al-Qabu.[21] According to Petersen, remains of the Palestinian village at the site include the church, a mosque, and a shrine for Shaykh Ahmad al-Umari. The mosque is a square structure, with a courtyard, and it appears to be built of stones removed from the old church.[29]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Palmer, 1881, p. 297

- ^ Jump up to: a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58 Archived 2018-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #348. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khalidi, 1992, pp. 307-308.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morris, 2004, p. 520, note 111

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khalidi, 1992, p. 307

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green, 1994, p. 209. Cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 248

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pringle, 1998, p. 156

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 100. Also cited in Pringle, 1998, p. 157

- ^ Pringle, 1998, p. 157

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 124

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 326

- ^ Kiepert, 1856, Map of Southern Palestine

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pp. 384-385

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 155

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, pp. 144-145

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p.25. Also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 307

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 42

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Khalidi, 1992, p. 308

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p.282

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 519

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 519-520, note105

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 520, note 106

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 520, note 109

- ^ PAM (=Palestine Antiquities Museum) File 154, Cited in Petersen, 2001, p. 248

Bibliography[]

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Billig, Ya’akov (2005-04-19). "En Qobi" (117). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Jordan. Dāʾirat al-Āthār al-ʻĀmmah (1991). Annual of the Department of Antiquities, Volume 35. Dept. of Antiquities, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 965-208-107-8. Cited in Petersen, 2001

- Weiss, Danny (2006-09-20). "En Qobi" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Zissu, Boaz; Weiss, Danny (2008-02-11). "En Qobi" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links[]

- Welcome To al-Qabu

- al-Qabu, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Mosque of Sheikh Mahmud el-‘Ajami

- Al-Qabu, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Al-Qabu, Palestine Family.net

- Tour of al-Qabu, 22.1.11, Zochrot

- Arab villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

- District of Jerusalem