Al-Shajara, Tiberias

Al-Shajara

الشجرة al-Shajera | |

|---|---|

| Etymology: "the Tree"[1] | |

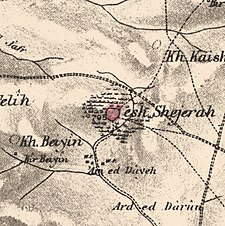

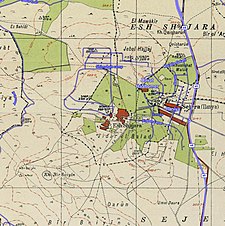

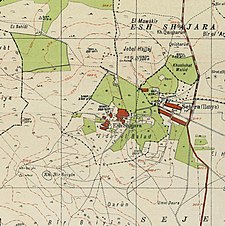

A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Shajara, Tiberias (click the buttons) | |

Al-Shajara Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°45′16″N 35°23′56″E / 32.75444°N 35.39889°ECoordinates: 32°45′16″N 35°23′56″E / 32.75444°N 35.39889°E | |

| Palestine grid | 187/239 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Tiberias |

| Date of depopulation | May 6, 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,754 dunams (3.754 km2 or 1.449 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 770[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Ilaniya |

Al-Shajara (Arabic: الشجرة) was a Palestinian Arab village depopulated by Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War when its residents were forcefully evacutaed and became refugees. It was located 14 kilometers west of Tiberias on the main highway to Nazareth near the villages of Lubya and Hittin. The village was very close to the city of Nazareth, about 5 kilometers away.

The village was the fourth largest by area in Tiberias district. Its economy was based on agriculture. In 1944/45 it had 2,102 dunams (505 acres) planted with cereals and 544 dunams (136 acres) either irrigated or fig and olive orchards.

Al-Shajara was the home village of the cartoonist Naji al-Ali.

History[]

Ceramics from the Byzantine era have been found here,[5] while the Crusaders referred to al-Shajara by "Seiera".[6] The Arabic name of the village ash-Shajara translates as "the Tree".

Ottoman era[]

In 1596, al-Shajara was part of the Ottoman Empire, nahiya (subdistrict) of Tiberias under the liwa' (district) of Safad with a population of 60 Muslim families and 12 Muslim bachelors. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 25% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olives, fruits and cotton. Taxes was also paid goats, beehives, orchards, and a press that was used either for processing olives or grapes; a total of 16,250 Akçe. 5/24 of the revenue went to a Waqf, the rest was Ziamet land.[7]

A party of French cavalry was apparently stationed in the village during Napoleon's invasion of 1799.[8] A map from the same campaign by Pierre Jacotin showed the place, named as Chagara.[9]

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss traveler to Palestine who passed through the area around 1812, noted that the plain around the village was covered with wild artichoke,[10][11] while William McClure Thomson said that al-Shajara (Sejera) was one of several villages in the area which was surrounded by gigantic hedges of cactus.[12] He also noted the great oak woods in the vicinity.[13]

Victor Guérin visited in 1875, and "discovered the ruins of a rectangular edifice built of cut stones, and oriented from west to east. Its height is 31 feet, and its breadth 18 feet 8 inches. Six monolithic columns decorated the interior, which they divided into two naves. Capitals are lying about on the ground, apparently of Byzantine style. This church was used for a mosque, for the traces of a mihrab are to be seen at the south end. On a fine slab, lying on the ground, are read the Greek letters ΔΟΚΙ, each about four and a half inches high, and on a second slab the letter Δ placed above a I."[14]

Gottlieb Schumacher found old graves and other antiquities when he explored the area in the 1880s.[15] In the late nineteenth century, the village of al-Shajara was a stone-built village and had about 150 residents. The village was surrounded by arable land on which there were fig and olive trees, and there was a spring to the south.[16]

In 1907, the residents of the nearby Jewish settlement of Sejera moved onto land within the village boundaries after buying it from the Sursock family (see Sursock Purchase). This triggered attacks from al-Shajara residents.[17]

British Mandate era[]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, the population of Sjajara was 543 residents; 391 Muslims, 100 Jews and 52 Christians.[18] where the Christians were all Orthodox.[19] By the 1931 census, Esh Shajara had 584 persons; 559 Muslims and 28 Christians, in a total of 123 houses.[20]

This had increased to 770 Muslims when the last census was made in the 1945 statistics.[2][3][21] There were 720 Muslim and 50 Christians.[22] In 1944/45 the village had 2,102 dunams of land used for cereals, and 544 dunams irrigated or used for orchards,[21][23] while 100 dunams were built-up (urban) area.[24]

1948, and aftermath[]

During the 1948 War, the Arab Liberation Army defending al-Shajara battled Israeli forces in the village in early March.[25] It was captured by Israel on May 6, 1948, by the 12th Battalion, Golani Brigade — the entire population fled leaving twenty dead.[26][4][27]

The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the place in 1992: "The ruins of houses and broken steel bars protrude from beds of wild vegetation. One side of an arched doorway still stands. The western part of the site and the nearby hill are covered with cactus. Cattle barns belonging to the nearby settlement of Ilaniyya stand on the southern and eastern sides of the site. On the northern edge is a wide, deep well with a spiral stairway inside (used for periodic cleaning and maintenance of the well). Fig, doum-palm, and chinaberry trees grow in the area.[21]

People from al-Shajara[]

- Naji al-Ali, cartoonist, assassinated in London 1987.

- "Abu Arab" Ibrahim Mohammed Saleh, Poet and Singer of the Palestinian Revolution, fled to Syria in 1948, returned in 2011, died in Homs, Syria in April 2014

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 134

- ^ Jump up to: a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 12

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 73

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morris, 2004, p. xvii, village #100. Also gives the cause of depopulation.

- ^ Dauphin, 1998, p.725

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p.540

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 190.

- ^ Thomson, 1860, p.216

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 166 Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burckhardt, 1822, p. 333

- ^ Also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 541

- ^ Thomson, 1860, p.117

- ^ Thomson, 1860, p.136

- ^ Guérin, 1880, pp. 183 -184, as given in Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 414

- ^ Schumacher, 1889, pp. 75-79

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p.361. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p.541

- ^ Khalidi, 2010, pp. 103-106.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Tiberias, p. 39

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XVI, p. 51

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 85

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Khalidi, 1992, p.541

- ^ Village Statistics April 1945, The Palestine Government, p. 7 Archived 2012-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 123

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 173

- ^ Tal, 2004, pp. 338-340

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p.541. Quoting New York Times. Also, according to the Haganah 'inhabitants fled leaving their dead behind.'

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 186, note #179, p. 275

Bibliography[]

- Alexandre, Yardenna (2011-12-19). "Ilaniyya Final Report" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2013-05-10. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Burckhardt, J.L. (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. London: J. Murray.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- Khalidi, R. (2010). Palestinian Identity. Columbia University Press. ISBN 023152174X.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Saulcy, L.F. de (1854). Narrative of a journey round the Dead Sea, and in the Bible lands, in 1850 and 1851. 2, new edition. London: R. Bentley. (p. 384)

- Schumacher, G. (1889). "Recent discoveries in the Galilee". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 21: 68–78.

- Tal, D. (2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. ISBN 1135775133.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

External links[]

- Welcome to al-Shajara

- al-Shajara, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Shajara from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Al-Sajarah, from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Tour to A-Shajra, November 25, 2006 Zochrot

- Booklet about Shajara, downloadable, from Zochrot

- Arab villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

- District of Tiberias